Downloaded from Manchesterhive.Com at 09/24/2021 11:11:37PM Via Free Access 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Communauté D'agglomération De Bar-Le-Duc Sud Meuse

Communauté d’agglomération de Bar-le-Duc Sud Meuse Portrait d’agglomération DATES CLÉS • 1er janvier 2013 : création de la nouvelle Communauté d’Agglomération regroupant 27 communes • 1er Janvier 2014 : extension de la Communauté d’Agglomération à 32 communes • 1er janvier 2015 : extension à 33 communes (séparation de Loisey-Culey en 2 communes) • Président : Bertrand Pancher depuis le 14 avril 2014 Nombre de Superficie Population communes (km²) CA de Bar-le-Duc 36 187 33 400 Ville Centre 15 950 1 23.62 SCoT 65 088 124 1 745 COMPÉTENCES DE LA COMMUNAUTÉ D’AGGLOMÉRATION DE BAR-LE-DUC SUD MEUSE Les « compétences obligatoires » • En lien avec l’aménagement de l’espace : Aménagement numérique d’intérêt communautaire ; • Développement économique Numérisation du cadastre et Système d’Information • Aménagement de l’espace communautaire Géographique (SIG). • Equilibre social de l’habitat • En lien avec la protection de l’environnement : Hydraulique ; • Politique de la Ville Mise en valeur des paysages – Chemin de randonnées. • Accueil des gens du voyage • En lien avec l’attractivité du territoire communautaire : • Collecte et traitement des déchets des ménages Soutien à des manifestations ou évènements sportifs ou et déchets assimilés culturels d’intérêt communautaire, le cas échéant organisés par les communes membres ; Schéma communautaire de Les « compétences optionnelles » développement des enseignements artistiques ; Schéma communautaire de développement de la lecture publique ; • Assainissement des eaux usées Actions en faveur de la formation professionnelle et de • Eau l’enseignement supérieur ; Charte de coopération en matière • Protection et mise en valeur de l’environnement d’accueil scolaire et périscolaire ; Aménagement des places et du cadre de vie publiques ; Schéma d’harmonisation des cœurs de villages. -

High-Speed Railway Axis East

Priority axis No 4 – Ongoing High-speed railway axis east The new high-speed railway link between Germany and France will benefit European citizens from west and east alike, speeding up journey times and providing a more environment-friendly alternative to air travel on key routes. What is the axis? What is its current status? The project aims to interconnect the high-speed rail networks of In France, construction of the new high-speed line between France and Germany, as well as to improve the railway link Vaires and Baudrecourt started in January 2002.Track-laying between France and Luxembourg. Its three parts are a new works started in October 2004. At that time, ground works for the 300 km long high-speed, passenger-only rail line from Paris to new line had been fully completed, and about 70 % of the Baudrecourt (near Metz) with a commercial speed of 320 km/h; bridges and tunnels were in place. Infrastructure works should be upgrading of the Saarbrücken–Mannheim section (on the Paris– completed in summer 2006, allowing test runs to start towards Metz–Frankfurt–Berlin railway corridor, the improvement of the end of 2006, and the new line to open in summer 2007. which is subject to a bilateral ministerial agreement concluded in The ‘TGV Est’ project includes the construction of three new 1992), for 200 km/h running; and upgrading of the Metz– railway stations of which Champagne–Ardenne and Meuse form Luxembourg line. part of the first phase, i.e. priority axis No 4 (the third station – The Paris–Baudrecourt section is the first phase of the French Lorraine – belongs to priority axis No 17). -

Living with the Enemy in First World War France

i The experience of occupation in the Nord, 1914– 18 ii Cultural History of Modern War Series editors Ana Carden- Coyne, Peter Gatrell, Max Jones, Penny Summerfield and Bertrand Taithe Already published Carol Acton and Jane Potter Working in a World of Hurt: Trauma and Resilience in the Narratives of Medical Personnel in Warzones Julie Anderson War, Disability and Rehabilitation in Britain: Soul of a Nation Lindsey Dodd French Children under the Allied Bombs, 1940– 45: An Oral History Rachel Duffett The Stomach for Fighting: Food and the Soldiers of the First World War Peter Gatrell and Lyubov Zhvanko (eds) Europe on the Move: Refugees in the Era of the Great War Christine E. Hallett Containing Trauma: Nursing Work in the First World War Jo Laycock Imagining Armenia: Orientalism, Ambiguity and Intervention Chris Millington From Victory to Vichy: Veterans in Inter- War France Juliette Pattinson Behind Enemy Lines: Gender, Passing and the Special Operations Executive in the Second World War Chris Pearson Mobilizing Nature: the Environmental History of War and Militarization in Modern France Jeffrey S. Reznick Healing the Nation: Soldiers and the Culture of Caregiving in Britain during the Great War Jeffrey S. Reznick John Galsworthy and Disabled Soldiers of the Great War: With an Illustrated Selection of His Writings Michael Roper The Secret Battle: Emotional Survival in the Great War Penny Summerfield and Corinna Peniston- Bird Contesting Home Defence: Men, Women and the Home Guard in the Second World War Trudi Tate and Kate Kennedy (eds) -

Ardennes (8) Aube (10) Marne (51) Meuse (55) Moselle (57) Bas-Rhin

Haute-Marne Meurthe et France/ France Ardennes (8) Aube (10) Marne (51) (52) Moselle (54) Meuse (55) Moselle (57) Bas-Rhin (67) Haut-Rhin (68) Vosges (88) Grand Est métropolitaine 2020-10-14 GEOGRAPHIE Charleville- Châlons- Préfecture Mézières Troyes en-Champagne Chaumont Nancy Bar-le-Duc Metz Strasbourg Colmar Epinal Strasbourg Paris Nombre d'arrondissements 4 3 4 3 4 3 5 5 4 3 38 321 Nombre de cantons 19 17 23 17 23 17 27 23 17 17 200 2 205 Nombre de communes (2020) 449 431 613 426 591 499 725 514 366 507 5121 35 287 Nombre d’EPCI (2020) 8 13 14 8 18 15 22 24 16 11 149 1 240 - Dont métropoles et communautés urbaines 1 (CU) 1 1 1 4 (3 métropoles) 35 (21 métropoles) - Dont communautés d'agglomérations 1 1 2 2 1 2 5 1 3 2 20 222 Nombre de SCoT (Fév. 2020)) 2 3 4 3 2 2 5 7 7 2 37 470 DEMOGRAPHIE Population 2017 (au 1er janvier 2020) 273 579 310 020 568 895 175 640 733 481 187 187 1 043 522 1 125 559 764 030 367 673 5 549 586 64 897 954 Evolution moyenne annuelle (2012-2017) –0,66 0,29 –0,72 0,01 –0,59 –0,06 0,38 0,23 –0,51 0,39 Superficie en km² 5 229 6 004 8 162 6 211 5 246 6 211 6 216 4 755 3 525 5 874 57 433 551 695 Nb d’ha artificialisés par an (entre 2009 et 2017) 181 151 232 77 171 55 403 263 217 174 1 924 28 191 Densité 2017 (hab/km²) 52,3 51,6 69,7 28,3 139,8 30,1 167,9 236,7 216,7 62,6 96,7 104,9 Part des moins de 25 ans (2017) 27,4 29,5 30,8 25,3 30,6 26,9 27,5 29,3 28,0 25,8 28,6 29,7 Part des 65 ans ou plus (2017) 20,7 20,9 18,8 24,0 18,8 21,6 19,0 17,8 19,0 23,2 19,4 19,4 Indice de vieillissement (2017) 87,0 86,0 77,0 112,0 -

Practical Projects Between Strasbourg and Kehl

P. 2 Events The Frankfurt-Slubice cooperation centre In brief P. 3 Europe news MOT news P. 4 Press review Practical projects between Strasbourg and Kehl A bridge between France and Germany, the Strasbourg-Kehl cross-border conurbation is at the heart of the Upper Rhine region and, more locally, of the Strasbourg-Ortenau Eurodistrict, a cooperation body set up in 2005 which established itself as an EGTC in 2010. Close cooperation has been under way for urban development competition was held many years between the two cities, with a covering “La Cour des Douanes” on the broad range of projects to meet the needs French side and the “Zollhofareal” on the of the populations. A few examples: German side, judged by a French-German - The aim of the “EcoCités Strasbourg, jury. The winning teams were revealed on métropole des deux-rives”* urban 18 January. development project is to lay the - The Cross-border nursery project meets Roland RIES Jacques BIGOT foundations of a sustainable, attractive the needs of the two cities for additional Senator - Mayor of Mayor of Illkirch- and inclusive cross-border metropolis, places in collective facilities for children Strasbourg Graffenstaden open to the Rhine and to Europe. from two and a half months to three Honorary president President of the Strasbourg Consistent with this project, the public years of age. An innovative structure in of the MOT Urban Community transport master plan includes the terms of both its architectural design and Boost the construction of Europe through cross-border extension of the Strasbourg tramway to its teaching project, which will combine cooperation Kehl to ease mobility on both banks of French and German approaches to early “On 24 and 25 April 2013, Strasbourg will have the pleasure the Rhine. -

The Battle of the Meuse-Argonne, 1918: Harbinger of American Great Power on the European Continent?

Foreign Policy Research Institute FOOTNOTES www.fpri.org The Newsletter of FPRI’s Wachman Center May 2012 The Battle of the Meuse-Argonne, 1918: Harbinger of American Great Power on the European Continent? By Michael S. Neiberg Michael S. Neiberg is Professor of History at the US Army War College and an established authority on the Great War. His writing has been recognized with a Choice Outstanding Academic Title award, a Tomlinson Prize for best book on World War I, and a Harry Frank Guggenheim fellowship. In 2011, Harvard University Press published his Dance of the Furies: Europe and the Outbreak of World War I which looked at popular reactions to the outbreak of the Great War. In 2012, Basic Books will publish his Blood of Free Men: The Liberation of Paris, 1944. This essay is based on his talk to FPRI’s History Institute for Teachers on “Great Battles and How They Have Shaped American History,” cosponsored and hosted by the First Division Museum at Cantigny, Wheaton, IL, on April 21-22, 2012. Audio/Video file, powerpoints, and texts from the weekend conference are available here: http://www.fpri.org/education/1204greatbattles/ Standing on Governor’s Island, just south of Manhattan, Elizabeth Coles Marshall watched her husband George board the SS Baltic with 190 of his fellow US Army officers. They were the vanguard of the new American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) command system, led by Gen. John Pershing. In order to maintain secrecy, the men were directed to come to Governor’s Island in civilian clothes, although many wore their Army shoes and a few even carried swords on their belts. -

Les Sous-Préfets De Belfort Les Administrateurs Du Territoire De Belfort

Les sous-préfets de Belfort Sous-préfet Prise de fonction Poste précédent Poste Suivant 1 François-Martin Burger 13 avril 1800 Commissaire du directoire exécutif de Belfort Mort en fonction Général de division en retraite, 2 François-Xavier Mengaud 25 janvier 1805 Retraite conseiller municipal de Belfort 3 Louis Prudhomme 22 août 1814 Sous-préfet de Dinant (Belgique) Chassé pendant les Cent-Jours 4 Léon-Nicolas Quellain 25 mars 1815 Maire de Belfort Notaire, Maire de Delle 5 François-Xavier Mengaud 15 avril 1815 Retraite Retraite 6 Louis Prudhomme Juillet 1815 En exil Retiré à Paris 7 René de Brancas 2 septembre 1815 Propriétaire Sous-préfet de Dieppe (Seine-Maritime) 8 Charles Lepère 6 septembre 1820 Sous-préfet de Trévoux (Ain) Sous-préfet de Lapalisse (Allier) 9 François de Tessières de la Bertinie 30 septembre 1820 Sous-préfet de Barbezieux (Charente) Sous-préfet de Verdun (Meuse) 10 Philippe d'Agrain des Hubas 12 novembre 1823 Sous-préfet de Verdun (Meuse) Mort en fonction 11 Louis-Michel Sido 25 janvier 1829 Conseiller à la préfecture du Haut-Rhin Sous-préfet de Wissembourg (Bas-Rhin) 12 Alexandre Jaussaud 28 septembre 1830 Sous-préfet de Langres (Haute-Marne) Sous-préfet de Montmorillon (Vienne) 13 Pierre Tinel 30 mars 1833 Sous-préfet de Montmorillon (Vienne) Retraite 14 Bernard Laurent Mars 1848 Avocat à Colmar (Haut-Rhin) ? 15 Laurent Demazières 4 avril 1848 Conseiller de préfecture du Haut-Rhin Conseiller de préfecture (Ain) 16 Charles Groubeltal 9 août 1848 Sous-préfet de Ste-Menehould (Marne) Imprimeur à Blois (Loir-et-Cher) -

Services Command Center for the Itinerary - Givet Tel

Areas of competence of the different territorial units within the waterways of the North-East Directorate of Voies navigables de France Territorial unit competent on the Meuse Ardennes and sector of Ardennes services command center for the itinerary - Givet Tel. +33 (0)3 24 42 01 57 sector of Meuse upstream to announce oneself navigation timesst number command center for the itinerary - Verdun 0 800 519 665 free phone December Tel. +33 (0)3 29 83 74 21 st Belgium 1 January to 31 59 des 4 Cheminées Territorial unit competent on commercial boats from Givet the Moselle 2021 command center for the Moselle On all the river network managed by North-East Directorate of VNF, all commercial boats must itinerary 24 hours day announce their entry onto the network or their departure from one of the ports situated on Koenigsmacker lock the network, giving their destination to the regional announcement centre (free phone Seasonal command center Tel. +33 (0)3 82 55 01 58 of Semuy no. 0 800 519 665), which will take calls every day it is open until 3 pm for trips beginning the Charleville (from 1 april to 31 october) next day. Mézières Tel. +33 (0)3 24 71 44 88 Netherlands s Germany Commercial boats wishing to take advantage of passage on request outside the free naviga- e n n (Junction with the Rhine in Koblenz) e tion times on the canalised part of the Moselle river put in a request to the regional announce- l d a r Luxembourg t A n h a ment centre before 3 pm. -

Meuse, France)

Contributions to Zoology, 72 (2-3) 91-93 (2003) SPB Academic Publishing bv, The Hague Decapod crustaceans from the Kimmeridgian of Bure (Meuse, France) Gérard Breton Cédric Carpentier²Vincent Huault² & Bernard Lathuilière ¹, 2 1Museum d’Histoire naturelle, Place du Vieux-Marche, F-76600 Le Havre, France; Universite Henri Poincare Nancy 1, BP 239, F-54506 Vandceuvre-les-Nancy cedex, France Keywords: : Decapoda, Axiidae, Erymidae, Paguridae, Kimmeridgian, France Abstract Systematics in of Wells being dug at Bure, France, strata Kimmeridgian age The material comprises the following taxa: have uncovered a diverse fauna of reptant decapods. Superfamily Thalassinoidea Latreille Family Axiidae Huxley Introduction Genus Etallonia Oppel (= Protaxius Beurlen) ANDRA, the French National radioactive waste Etallonia isochela (Woodward, 1876). (Fig. 1) managementagency, is currently constructing two large wells at Bure(Meuse, France) with diameters About thirty specimens are available from the of 5 to 6 m and an expected final depth close to Cymodoce up to the Autissiodorensis zones; pro- 500 m, in order to create an underground research podus flat (E/l = 1.8-2.15), shape rectangular, fin- of laboratory. Recently, depending on progress ger triangular, stocky and quite regularly oriented been construction, three of us (CC, VH, BL) have downwards; chela subcheliform; dactylus 1.5 times collecting fossils from the site, from deposits ex- longer than finger. In 50% of specimens fingers in The tracted slices of about 2 m in thickness. show a tubercle at mid-length; we suggest this to construction of these wells represents a unique possibly represent a sexual character. In associated various subsurface obser- opportunity to compare the pairs, anisochely is very moderate, similar to vations (sedimentology, paleontology, geochemis- type specimen. -

International River Basin District Meuse Characteristics, Review Of

International River Basin District Meuse Characteristics, Review of the Environmental Impact of Human Activity, Economic Analysis of Water Use Roof report on the international coordination pursuant to Article 3 (4) of the analysis required by Article 5 of Directive 2000/60/EC establishing a framework for Community action in the field of water policy (Water Framework Directive) Liège, 23 March 2005 Rapport final MEUSE_angl_def - 1 - 02-08-2005 The following abbreviated title may be used to refer to this report: “International River Basin District Meuse – Analysis, Roof Report, International Meuse Commission, 2005” Every use of this report shall be accompanied by a reference to it. This shall also be the case when maps or data taken from the report are used or made more widely available The maps in the annexes to this report were drawn up by the Walloon Region (Direction Générale des Ressources Naturelles et de l”Environnement), on the basis of data provided for by the Parties. Their commercial use is prohibited. This report is available in French, Dutch, and German. English not being one of the IMC’s official languages, the English version of this report is not an official translation and is only provided to make the report more widely available. International Meuse Commission (Commission internationale de la Meuse) Esplanade de l”Europe 2 B-4020 Liège Tel: +32 4 340 11 40 Fax +32 4 349 00 83 [email protected] www.meuse-maas.be . Rapport final MEUSE_angl_def - 2 - 02-08-2005 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 International Coordination within the International River Basin District Meuse..................... -

Argonne Offensive

“The heroism of the foot soldier is defeated by the Volume I, Chapter 4 steelworker of the colossal factory who builds the huge cannons and by the engineer who mixes the long-irrtating The Weapons of gases in the back of his laboratory. The forces of matter annihilate the forces of bravery.” Abbot Charles Thellier de Poncheville, the Meuse- Military Chaplain, Verdun, France, 1916 Argonne Offensive How did soldiers who rest in the Meuse-Argonne Cemetery experience the collision of modern industry and military tradition? Matt Deegan German soldiers flee a gas attack at the front lines in Flanders, Belgium in September 1917. (Photo credit: U.S. National Archive) Section 1 Introduction In World War I, soldiers rode into battle on horses as airplanes The U.S.’s greatest battle of the Great War was a 47-day flew overhead. They clutched bayonets while dodging machine offensive in the Meuse-Argonne region of northeastern France. gun fire. Army couriers pedaled bicycles past tanks that weighed This chapter uses the Meuse-Argonne Offensive and the Meuse- six tons. And troops ran forward on the battlefield, sometimes Argonne American Cemetery as a window into the impact that into deadly clouds of gas. Factories and laboratories of the early modern weapons had on the war’s military tactics and on the toll 20th century concocted the world’s first industrial war, creating a they exacted on the soldiers themselves. How were these battlefield that juxtaposed the old and the new: centuries-old weapons used in the Meuse-Argonne? What was the best way to military tactics with modern technology. -

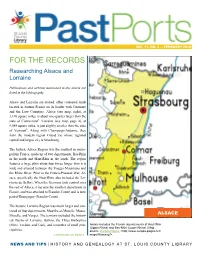

FOR the RECORDS Researching Alsace and Lorraine

VOL. 11, NO. 2 — FEBRUARY 2018 FOR THE RECORDS Researching Alsace and Lorraine Publications and websites mentioned in this article are listed in the bibliography. Alsace and Lorraine are storied, often contested lands located in eastern France on its border with Germany and the Low Countries. Alsace (see map, right), at 3,196 square miles, is about one-quarter larger than the state of Connecticut1. Lorraine (see map, page 4), at 9,089 square miles, is just slightly smaller than the state of Vermont2. Along with Champaign-Ardenne, they form the modern region Grand Est whose regional capital and largest city is Strasbourg. The historic Alsace Region was the smallest in metro- politan France, made up of two departments, Bas-Rhin in the north and Haut-Rhin in the south. The region features a large plain about four times longer than it is wide and situated between the Vosges Mountains and the Rhine River. Prior to the Franco-Prussian War, Al- sace, specifically the Haut-Rhin, also included the Ter- ritoire de Belfort. When the Germans took control over the rest of Alsace, it became the smallest department in France, and was attached to Franche-Comté and is now part of Bourgogne- Franche-Comté. The historic Lorraine Region was much larger and con- sisted of four departments, Meurthe-et-Moselle, Meuse, Moselle, and Vosges. The territory included the histori- ALSACE cal Duchy of Lorraine, Barrois, the Three Bishoprics (Metz, Verdun, and Toul), and a number of small prin- Alsace includes the French départements of Haut-Rhin (Upper Rhine) and Bas-Rhin (Lower Rhine) | Map cipalities.