Florida Historical Quarterly

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ludacris Word of Mouf Full Album

Ludacris, Word Of Mouf Full Album Zip 1 / 4 Ludacris, Word Of Mouf Full Album Zip 2 / 4 3 / 4 Word Of Mouf | Ludacris to stream in hi-fi, or to download in True CD Quality on Qobuz.com.. Play full-length songs from Word Of Mouf by Ludacris on your phone, computer and home audio system with Napster.. Ludacris - Word Of Mouf - Amazon.com Music. ... Listen to Word Of Mouf [Explicit] by Ludacris and 50 million songs with Amazon Music Unlimited. $9.99/month .... Download Word Of Mouf (Explicit) by Ludacris at Juno Download. Listen to this and ... Block Lockdown (album version (Explicit) feat Infamous 2-0). 07:48. 96.. 2001 - Ludacris - ''Wоrd Of Mouf''. Tracklist. 01. "Coming 2 America". 02. ... Tracklist. 01 - Intro. 02 - Georgia. 03 - Put Ya Hands Up. 04 - Word On The Street (Skit).. Word of Mouf is the third studio album by American rapper Ludacris; it was released on November 27, 2001, by Disturbing tha Peace and Def Jam South.. Word of Mouf by Ludacris songs free download.. Facebook; Twitter .. Explore the page to download mp3 songs or full album zip for free.. ludacris word of mouf zip ludacris word of mouf songs ludacris word of mouf download ludacris word of mouf full album . View credits, reviews, tracks and shop for the 2001 CD release of Word Of Mouf on Discogs. ... Word Of Mouf (CD, Album) album cover ... Tracklist Hide Credits .... Ludacris - Back for the First Time (Full album). Enoch; 16 ... Play & Download Ludacris - Word Of Mouf itunes zip Only On GangstaRapTalk the.. Download Word of Mouf 2001 Album by Ludacris in mp3 CBR online alongwith Karaoke. -

Copyright by Eric Alan Ratliff 2003

Copyright by Eric Alan Ratliff 2003 The Dissertation Committee for Eric Alan Ratliff Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: The Price of Passion: Performances of Consumption and Desire in the Philippine Go-Go Bar Committee: ____________________________________ Douglas Foley, Supervisor ____________________________________ Kamran Asdar Ali ____________________________________ Robert Fernea ____________________________________ Ward Keeler ____________________________________ Mark Nichter The Price of Passion: Performances of Consumption and Desire in the Philippine Go-Go Bar by Eric Alan Ratliff, B.A., M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2003 Acknowledgements A project of this scope and duration does not progress very far without the assistance of many people. I would first like to acknowledge my dissertation committee members for their advice and encouragement over these many years. Douglas Foley, Ward Keeler, Robert Fernea, Kamran Ali and Mark Nichter provided constructive comments during those times when I could not find the right words and continuing motivation when my own patience and enthusiasm was waning. As with the subjects of my study, their ‘stories’ of ethnographic practice were both informative and entertaining at just the right moments. Many others have also offered inspiration and valuable suggestions over the years, including Eufracio Abaya, Laura Agustín, Priscilla Alexander, Dr. Nicolas Bautista, Katherine Frank, Jeanne Francis Illo, Geoff Manthey, Sachiyo Yamato, Aida Santos, Melbourne Tapper, and Kamala Visweswaran. This research would never have gotten off the ground without the support of the ReachOut AIDS Education Foundation (now ReachOut Foundation International). -

The School Board of Escambia County, Florida

THE SCHOOL BOARD OF ESCAMBIA COUNTY, FLORIDA MINUTES, MAY 18, 2021 The School Board of Escambia County, Florida, convened in Regular Meeting at 5:30 p.m., in Room 160, at the J.E. Hall Educational Services Center, 30 East Texar Drive, Pensacola, Florida, with the following present: Chair: Mr. William E. Slayton (District V) Vice Chair: Mr. Kevin L. Adams (District I) Board Members: Mr. Paul Fetsko (District II) Dr. Laura Dortch Edler (District III) Mrs. Patricia Hightower (District IV) School Board General Counsel: Mrs. Ellen Odom Superintendent of Schools: Dr. Timothy A. Smith Advertised in the Pensacola News Journal on April 30, 2021 – Legal No. 4693648 I. CALL TO ORDER Chair Slayton called the Regular Meeting to order at 5:30 p.m. a. Invocation and Pledge of Allegiance (NOTE: It is the tradition of the Escambia County School Board to begin their business meeting with an invocation or motivational moment followed by the Pledge of Allegiance.) Dr. Edler introduced Reverend Lawrence Powell, minister at Good Hope A.M.E. Church of Warrington in Pensacola, Florida. Reverend Powell delivered the invocation and Dr. Edler led the Pledge of Allegiance to the United States of America. b. Adoption of Agenda Superintendent Smith listed changes made to the agenda since initial publication and prior to this session. Chair Slayton advised that Florida Statutes and School Board Rule require that changes made to an agenda after publication be based on a finding of good cause, as determined by the person designated to preside over the meeting, and stated in the record. -

Thesis Finding Privacy in the Red-Light District

THESIS FINDING PRIVACY IN THE RED-LIGHT DISTRICT: AN ANALYSIS OF VICTORIAN ERA MEDICINE BOTTLES FROM THE VANOLI SITE (5OR.30) IN OURAY, COLORADO Submitted by Heather Horobik Department of Anthropology In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts Colorado State University Fort Collins, Colorado Fall 2011 Master’s Committee: Advisor: Mary Van Buren Ann Magennis Narda Robinson Copyright by Heather Horobik 2011 All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT FINDING PRIVACY IN THE RED-LIGHT DISTRICT: AN ANALYSIS OF VICTORIAN ERA MEDICINE BOTTLES FROM THE VANOLI SITE (5OR.30) IN OURAY, COLORADO A sample of bottles from the Vanoli Site (5OR.30), part of a Victorian era red- light district in Ouray, Colorado are examined. Previous archaeological studies involving the pattern analysis of brothel and red-light district assemblages have revealed high frequencies of medicine bottles. The purpose of this project was to determine whether a sense of privacy regarding health existed and how it could influence disposal patterns. The quantity and type of medicine bottles excavated from two pairs of middens and privies were compared. A concept of privacy was discovered to have significantly affected the location and frequency of medicine bottle disposal. A greater percentage of medicine bottles was deposited in privies, the private locations, rather than the more visually open and accessible middens. This study concludes that, while higher percentages of medicine bottles are found within brothel and red-light district locations, other factors such as privacy and feature type may affect the artifact patterns associated with such sites. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Many people helped and supported me throughout the process involved in completing this thesis. -

Ludacris the Red Light District Full Album Zip

Ludacris, The Red Light District Full Album Zip ERROR_GETTING_IMAGES-1 Ludacris, The Red Light District Full Album Zip 1 / 2 Hood Starz.com].rar hosted on mediafire.com 80.48 MB, Ludacris Chicken N Beer ... Ludacris, The Red Light District Full ;Enoch; 17 videos; 147,667 views חנוך .(Album Zip Download.. Ludacris - The Red Light District (Full album + Bonus Track Last updated on Jun 26, 2015. Subscribe! Play all. Share.. Find Ludacris discography, albums and singles on AllMusic. ... The Red Light District. 2004. The Red Light District · Def Jam South · Disturbing tha Peace. 2005.. Tracklist: 1. Intro, 2. Number One Spot, 3. Get Back, 4. Put Your Money, 5. Blueberry Yum Yum, 6. Child Of The Night, 7. The Potion, 8. Pass Out, 9. Skit, 10.. 2000 - Ludacris - ''Back For The First Time''. Tracklist. 01. "U Got a Problem?" 02. .... 2004 - Ludacris - ''The Red Light District''. Tracklist. 01. "Intro" Timbaland. 02.. Ludacris – The Red Light District. The Red Light District (CD, Album) album cover. More Images · All Versions · Edit Release · Sell This ... Tracklist Hide Credits .... The red light district. ludacris 320 kbps . Ludacris release therapy itunes . tags ludacris the red light district. Ludacris, the red light district full album zip .... Ludacris - The Red Light District review: Inconsistent, but primarily ... Release Date: 2004 | Tracklist .... I haven't heard a full one after this. Calc. Ludacris – Chicken-N-Beer – Album Zip Quality: iTunes Plus AAC M4A ... songs lyrics, songs mp3 download, download zip and complete full album rar. ... DVD made by of Ludacris visiting the red-light district, a growroom, .... 4 Download zip, rar. -

Anti-Racism Topic Paper

CEDA Topic Paper Anti-Racism Proposal 2016-17 Policy Debate Claudette Colvin C.T. Vivian Chase Iron Eyes T. R. M. Howard Yuri Kochiyama Reies López Tijerina Daisy Lee Gatson Bates Anti-Racism Topic Paper April 2016 Janet Escobedo, Georgia State University; Samuel Hanks, Georgia State University; Nadia Hussein, Georgia State University; and Dr. Kevin Kuswa, Berkeley Preparatory in Tampa, Florida. —with advice and feedback from Rashad Evans, University of Puget Sound and Dr. Tim Barouch, Georgia State University Page 1 of 161 “Paradigms, however, are like frost crystals that disappear on exposure to the sun. As soon as one starts talking about a paradigm, its days are numbered,” R. Delgado, ’12 “We’re living in more chains today -- through lockdowns, ankle bracelets, halfway houses,… -- than we were in the early 1800’s. That’s something to think about.” Frank W. Wilderson, ‘14 CEDA Topic Paper Anti-Racism Proposal 2016-17 Policy Debate Table of Contents Anti-Racism Topic Area Proposal .................................................................................................................................................... 4 I. “Anti-Racial Exclusion” Phrasing ........................................................................................................................ 9 Racial Disparity ............................................................................................................................................................................... 18 Racial Inequality ............................................................................................................................................................................. -

CORRECTING and REPLACING Infospace Mobile and the Island Def Jam Music Group Produce First Live Ringtone at Hip Hop Sensation Ludacris' "Red Light District" CD

CORRECTING and REPLACING InfoSpace Mobile and The Island Def Jam Music Group Produce First Live Ringtone at Hip Hop Sensation Ludacris' "Red Light District" CD CORRECTION...by InfoSpace Mobile ATLANTA--(BUSINESS WIRE)--Dec. 2, 2004--Please replace the release with the following corrected version due to multiple revisions. The corrected release reads: INFOSPACE MOBILE AND THE ISLAND DEF JAM MUSIC GROUP PRODUCE FIRST LIVE RINGTONE AT HIP HOP SENSATION LUDACRIS' "RED LIGHT DISTRICT" CD RELEASE PARTY InfoSpace Mobile and The Island Def Jam Music Group are embarking on an industry first today as the leading producer of mobile content and top hip hop label will record and publish the first live music ringtone. The recording will take place at the CD release party for the award winning, multi-platinum Def Jam South artist Ludacris and his highly anticipated 4th album Red Light District tonight in Atlanta. "I wish all my fans could come to Atlanta for this party," said Ludacris. "This will be one of the only ways for my fans to hear me live before I tour!" The deal is indicative of how music artists are embracing the mobile medium as a means to extend their brands, interact with their fans on a personal level and create new revenue streams. In addition to recording four exclusive, live ringtones, InfoSpace Mobile will be offering consumers exclusive Ludacris images through its carrier partners. The first ringtone will be a live recording of the album's first single, "Get Back," and the exclusive images will be from the "Get Back" video, directed by renowned director, Spike Jonze. -

44 MILLION REASONS to #Savegamingrevenue

44 MILLION REASONS TO #SaveGamingRevenue ECGRA has strategically invested $44 million in 203 community and cultural assets, 700 entrepreneurs and business lenders, job Grants training and educational institutions, and & Loans neighborhoods and municipalities. 6:1 Return Local share gaming revenue is strengthening the nonprofit ECGRA has invested $6.7 million in business TM organizations and for-profit $ growth through Ignite Erie resulting in $39.6 businesses in the city of Erie that 22mm million in additional capital for local companies. are implementing the city’s in the City comprehensive plan. $18.1million in gaming revenue is inextricably woven into $ Erie’s cultural, recreational, 18.1mm and human services assets, ECGRA’s investments have resulted QUALITY dramatically improving quality in a cumulative impact of $87.2 OF LIFE of life for residents and quality million, supported and sustained of experience for tourists. 573 573 jobs, and generated $2.9 JOBS million in local and state taxes. Two Ways to Help WRITE. CALL. ADVOCATE EDUCATE yourself. for Erie’s share. Transforming a Region with Local Share Gaming Revenue: An Economic Impact Study Tell Your Legislators How ECGRA Read and Share ECGRA’s Grant Money Works for You! Economic Impact Study at ECGRA.org/impactstudy ECGRA.org/calltoaction prepared by: @ECGRA814 #IgniteErie ECGRA.org/igniteerie /ECGRA ECGRA_Economic Impact Full Page Ad.indd 1 3/1/17 3:11 PM 44 MILLION REASONS TO CONTENTS: From the Editors The only local voice for Sometimes we all need a news, arts, and culture. March 29, 2017 Editors-in-Chief: little health care. Brian Graham & Adam Welsh #SaveGamingRevenue or an entire week recently, one of our Managing Editor: staff members had a nagging cough. -

ECPSF Announces 2021 Mira Award Recipients

Kim Stefansson Escambia County School District Public Relations Coordinator [email protected] 850-393-0539 (Cell) NEWS RELEASE May 18, 2021 ECPSF Announces 2021 Mira Award Recipients Each year the Escambia County Public Schools Foundation has celebrated the unique gifts and creative talents of many amazing high school students from the Escambia County (Fla) School District’s seven high schools with the presentation of the Mira Creative Arts Awards. Mira is a shortened Latin term meaning, “brightest star,” and the awards were established by teachers to recognize students who demonstrate talents in the creative arts. Students are nominated by their instructors for this honor. The Foundation is thrilled to celebrate these artistic talents and gifts by honoring amazing high school seniors every year. This celebration was helped this year by the generosity of their event sponsor, Blues Angel Music. This year the Mira awards ceremony was held online. Please click here to view and download the presentation. Students are encouraged to share the link with their family members and friends so they can share in their celebration. Link: https://drive.google.com/file/d/10ERRfzPud1npcygZSYBuD7BF0- TBMWGK/view Students will receive a custom-made medallion during their school's senior awards ceremony so they may wear it during their graduation ceremony with their cap and gown. Congratulations go to all of the Mira awardees on behalf of the Escambia County Public Schools Foundation Board of Directors. The Class of 2021 Escambia County Public Schools -

41/95/3 1 Student Affairs ATO Chapters Chapter Photographs File

41/95/3 1 Student Affairs ATO Chapters Chapter Photographs File, 1867-2006 Note: The location of any oversized material is indicated next to the folder name where its cross reference sheet can be found. Box 1: ADRIAN COLLEGE Biographical, A-Z (2 folders) John Harper Dawson Frank Ewing JS Ralph Graty William Newton Jordan David Lott Harry Michener Myron Partridge Groups & Activities History House ALABAMA Biographical, A-W Richard C. Foster C.R. French Lawrence A. Long John L. Patterson Charley Pell Hendree P. Simpson Clanton Williams Groups & Activities Pledges History/House ALABAMA-BIRMINGHAM Charter, Petition, Installation ALABAMA-HUNTSVILLE Biographical, A-Z Groups & Activities Charter, Petition, Installation, Colony File ALBION COLLEGE Biographical, A-Z (2 folders) 41/95/3 2 Franklin F. Bradley Philip Curtis Homer Folks H. Leslie Hoffman Lynn Bogue Hunt Leonard “Fritz” Shurmur Mark Thorsby Albert A. Wilbur (oversized in room 106F, map case 3-8) Groups & Activities House AMERICAN Biographical, A-Y Guy Anselmo Dick Aubry Fred Carl Groups & Activities House/Housing APPALACHIAN STATE Biographical, A-Z Groups & Activities History House ARIZONA Biographical, A-W Michael O’Harro (oversize photo in Room 106F, Map Case 3-7) Groups & Activities House Box 2: ARIZONA STATE Biographical, A-W Housemother Vivian Corkhill Groups & Activities House & University ARKANSAS Biographical, C-T Groups & Activities, House, History ARKANSAS STATE Biographical, A-T 41/95/3 3 Groups & Activities, House ARKANSAS TECH Chartering Groups & Activities ATHENS STATE COLLEGE Biographical, A-Z Groups & Activities AUBURN Biographical, A-Z (2 folders) (oversized in oversized chapter photo box) Hugh M. Arnold Percy Beard Robert Lee Bullard John E. -

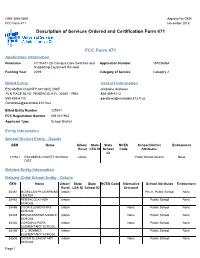

Description of Services Ordered and Certification Form 471 FCC

OMB 3060-0806 Approval by OMB FCC Form 471 November 2015 Description of Services Ordered and Certification Form 471 FCC Form 471 Application Information Nickname FY19-471-2A Campus Core Switches and Application Number 191036964 Supporting Equipment Revised Funding Year 2019 Category of Service Category 2 Billed Entity Contact Information ESCAMBIA COUNTY SCHOOL DIST Ghislaine Andrews 75 N PACE BLVD PENSACOLA FL 32505 - 7965 850-469-6112 850-469-6112 [email protected] [email protected] Billed Entity Number 127641 FCC Registration Number 0011611902 Applicant Type School District Entity Information School District Entity - Details BEN Name Urban/ State State NCES School District Endowment Rural LEA ID School Code Attributes ID 127641 ESCAMBIA COUNTY SCHOOL Urban Public School District None DIST Related Entity Information Related Child School Entity - Details BEN Name Urban/ State State NCES Code Alternative School Attributes Endowment Rural LEA ID School ID Discount 35481 MCMILLAN PK LEARNING Urban Pre-K; Public School None CENTER 35482 PENSACOLA HIGH Urban Public School None SCHOOL 35486 COOK ELEMENTARY Urban None Public School None SCHOOL 35493 BROWN BARGE MIDDLE Urban None Public School None SCHOOL 35494 CORDOVA PARK Urban None Public School None ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 35496 O. J. SEMMES Urban Public School None ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 35503 SUTER ELEMENTARY Urban None Public School None SCHOOL Page 1 BEN Name Urban/ State State NCES Code Alternative School Attributes Endowment Rural LEA ID School ID Discount 35504 WOODHAM MIDDLE -

MARCHING BAND MUSIC PERFORMANCE ASSESSMENT (Ver

MARCHING BAND MUSIC PERFORMANCE ASSESSMENT (ver. 01-02) FBA DISTRICT #: __1___ SEND THE COMPLETED FORM TO THE FBA EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR AND TO THE FSMA OFFICE NO LATER THAN 10 DAYS FOLLOWING EACH MUSIC PERFORMANCE ASSESSMENT EVENT. ASSESSMENT DATES: Oct. 12, 2002 ASSESSMENT SITE: J.M. Tate High School (Pensacola, FL) ADJUDICATORS CERTIFIED FIRST NAME LAST NAME (Y/N) #1 Marching & Maneuvering Tony Pike N #2 Marching General Effect Bert Creswell Y #3 Marching Music Performance #1 Richard Davenport Y #4 Marching Music Performance #2 David Fultz Y #5 Marching Auxiliary Barbara Fultz Y #6 Marching Percussion SHOW ONE ENTRY PER PERFORMING GROUP RATINGS: S=SUPERIOR; E=EXCELLENT; G=GOOD; F=FAIR; P=POOR; DNA=DID NOT ARRIVE; DQ=DISQUALIFIED; CO=COMMENTS ONLY SCHOOL NAME/PERFORMING GROUP # OF RATINGS PARTICIPANTS DIRECTOR/COUNTY JUDGE 1 JUDGE 2 JUDGE 3 JUDGE 4 JUDGE 5 JUDGE 6 FINAL 1. Baker School Band 45 S E S E E S Tony Chiarito / Okaloosa 2. Choctawhatchee Senior HS Band 190 S S S S S S Randy Nelson / Okaloosa 3. Crestview Senior High School Band 260 S S S S S S David Cadle / Okaloosa 4. Escambia High School Band 157 S S S S S S Doug Holsworth / Escambia 5. Ft. Walton Beach Senior HS Band 215 S S S S S S Randy Folsom / Okaloosa 6. Gulf Breeze High School Band 98 E E S S G S Neal McLeod / Santa Rosa 7. Jay High School Band 65 E E E E E E Connie Pettis / Santa Rosa 8. Milton High School Band 95 S E S S S S Gray Weaver / Santa Rosa 9.