Amnesia to Anamnesis: Commemoration of the Dead At

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Glamorization of Espionage in the International Spy Museum

W&M ScholarWorks Undergraduate Honors Theses Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 5-2015 Counter to Intelligence: The Glamorization of Espionage in the International Spy Museum Melanie R. Wiggins College of William and Mary Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses Part of the American Film Studies Commons, American Material Culture Commons, American Popular Culture Commons, Other American Studies Commons, and the Sociology of Culture Commons Recommended Citation Wiggins, Melanie R., "Counter to Intelligence: The Glamorization of Espionage in the International Spy Museum" (2015). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 133. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses/133 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Counter to Intelligence: The Glamorization of Espionage in the International Spy Museum A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in American Studies from The College of William and Mary by Melanie Rose Wiggins Accepted for____________________________________________________ (Honors, High Honors, Highest Honors) _________________________________________________________ Alan Braddock, Director _________________________________________________________ Charlie McGovern _________________________________________________________ -

Intelligence in American Society Roundtable Discussion with John Brennan, 9.15.15 Page 1 ______

Intelligence in American Society Roundtable Discussion with John Brennan, 9.15.15 Page 1 ______________________________________________________________________________ Notes: This transcription is smooth format, meaning that we do not transcribe filler words like um, er, ah, or uh huh. Nothing is rewritten or reworded. Transcriber notes such as [multiple voices/cross talk] or [laughs] etc. are italicized and contained within brackets. A word that the transcriber could not understand is indicated with a six-space line and a time code like this ______ [0:22:16]. A word that the transcriber was not sure of is bolded. Punctuation is to the best of our ability, given that this transcript results from a conversation. Key: Chesney Professor Bobby Chesney, Director of the Robert Strauss Center for International Security and Law Brennan John Brennan, CIA Director Ramos Elisa Ramos, Assistant Director of UT Student Activities Inboden Professor William Inboden, Executive Director of the Clements Center for National Security McRaven William McRaven, Chancellor of the University of Texas System Goss Porter Goss, Former Director of the CIA Slick Steve Slick, Director of the Intelligence Studies Project AQ Audience Question Chesney: Ladies and gentlemen, my name is Bobby Chesney and I am the Director of the Robert Strauss Center for International Security and Law. On behalf of myself and my dear friend and colleague, Will Inboden, the Executive Director of the Clements Center for National Security, let me say welcome to the University of Texas at Austin. Now nearly two years ago, the Strauss and Clements Centers joined forces to create something we call the Intelligence Studies Project. -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 116 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 116 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 165 WASHINGTON, TUESDAY, JULY 16, 2019 No. 119 House of Representatives The House met at 10 a.m. and was from Chester High School, where she awards, including: Woman of the Year called to order by the Speaker pro tem- was valedictorian of her senior class. from the First ARP Church, where she pore (Mr. CUELLAR). She enrolled in Erskine College and faithfully attended; the Cross of Mili- f graduated in 1941 with a degree in tary Service from the United Daughter music. of the Confederacy in 2001; the Quilt of DESIGNATION OF SPEAKER PRO Her first job was teaching junior high Valor award in 2015, presented by the TEMPORE school in Anderson, South Carolina, Quilts of Valor Foundations for vet- The SPEAKER pro tempore laid be- and she later joined WAVES, which erans touched by war; the National fore the House the following commu- stands for Women Accepted for Volun- Award in 2017, presented from DAR, the nication from the Speaker: teer Emergency Service, in 1943. She Daughters of the American Revolution WASHINGTON, DC, began her training at Mount Holyoke for Women in American History. July 16, 2019. College in South Hadley, Massachu- Mary Phillips Gettys is the proud I hereby appoint the Honorable HENRY setts, where she specialized in commu- and devoted grandmother of six grand- CUELLAR to act as Speaker pro tempore on nications while studying at Smith Col- children and three great-grandchildren. -

Inside Anbar MAJ BRENT LINDEMAN, UNITED STATES ARMY 75 Maoist Insurgency in India: Emerging Vulnerabilities GP CAPT SRINIVAS GANAPATHIRAJU, INDIAN AIR FORCE

May 2013 EDITORIAL STAFF From the Editor MICHAEL FREEMAN Executive Editor Welcome to the May issue of the Combating Terrorism Exchange. This issue ANNA SIMONS Executive Editor ELIZABETH SKINNER Managing Editor is unusual not for its length—although it is by far the longest issue we’ve yet RYAN STUART Design & Layout produced—but because in it we offer you two main articles that describe in exceptional detail the “Anbar Awakening” in Iraq (2004–6), from very EDITORIAL REVIEW BOARD different points of view. The backstory for both accounts begins when Abu Musab al-Zarqawi’s violent jihadi group al Qaeda in Iraq (AQI) had infested VICTOR ASAL the Al Qaim district of Anbar after fleeing Fallujah. Having presented them- University at Albany SUNY selves as freedom fighters, the militants were now beginning to show their true ALEJANDRA BOLANOS intent, using killings and coercion to keep the locals in line with their radical National Defense University al Qaeda agenda. Although most of the Anbar tribes opposed the U.S.-led LAWRENCE CLINE occupation, once the sheikhs realized that AQI was working to undermine their Naval Postgraduate School authority, they had a change of heart, and the Sahawa (Awakening) was born. STEPHEN DI RIENZO National Intelligence University Dr. William Knarr and his team of researchers at the U.S. Institute for Defense SAJJAN GOHEL Analysis concentrate on the U.S. Marine battalions deployed to the Al Qaim Asia Pacific Foundation district to fight AQI. Through extensive archival research and first-person inter- SEBASTIAN GORKA views with a significant number of Iraqi and American participants, Knarr National Defense University and his team describe how the Marines, initially wary and suspicious after a year of hard fighting, came to embrace the Awakening and, working with the JAKUB GRYGIEL sheikhs and their people, pushed back against AQI to free the Al Qaim district School of Advanced Int’l. -

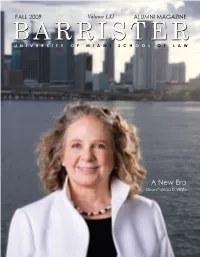

Fall 2009 Alumni Magazine

FALL 2009 Volume LXI ALUMNI MAGAZINE BARRISTERBARRISTER UNIVERSITY OF MIAMI SCHOOL OF LAW A New Era Dean Patricia D. White BARRISTER FALL ALUMNI MAGAZINE Patricia D. White Dean and Professor of Law Patrick O. Gudridge Associate Dean and Professor of Law Raquel M. Matas Associate Dean for Administration COVER22 10 Georgina A. Angones Assistant Dean for Alumni Relations and Development CONTENTS Jeannette F. Hausler ON THE COVER INSERT HONOR ROLL OF DONORS Dean of Students Emerita 1 Dean Patricia White - The Right Leader for Our Time NOTEWORTHY 25 Miami Scholars Program Michelle Valencia FEATURES Director of Publications 5 Alumna Carolyn Lamm Becomes Students from the Children & President of ABA Youth Law Clinic Fight for Patricia Moya Disabled Youths Graphic Designer A Conversation with Professor Bernard Oxman ALUMNI 28 Message from the President of Contributors Riding for Charity the Alumni Association Angelica Boutwell Nancy Funkhouser FACULTY BRIEFS New York Alumni Reception Mary Howard 12 New Faculty Law School Alumni Honored Tai Palacio Visiting Faculty Faculty Notes Mindy Rosenthal Florida Bar Reception Patty Shillington STUDENT HIGHLIGHTS Class of 1959 Angela Sturrup 18 UM Law Student Elected President of the Florida Bar’s Law Alex Laster Bowling Extravaganza Photographers Student Division Jenny Abreu Young Alumni Committee UM Law Wins Dubersein Richard Patterson Bankruptcy Moot Court Joshua Prezante Soia Mentschikioff’s Vision of Competition Legal Education Steve Schlackman Bob Soto UM Law Hosts the HNBA Class Notes BLSA Team Ranks Among In Memoriam The Barrister is published by the Nation’s Top Eight Office of Law Alumni Relations and Questionnaire Development, University of Miami NASALSA School of Law. -

Congressional Record—House H5858

H5858 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — HOUSE July 16, 2019 as President of the United States to ranking minority member of the Per- The bill also ensures that the men the manifest injury of the people of the manent Select Committee on Intel- and women of the IC have what they United States, and has committed a ligence. need to collect and analyze the intel- high misdemeanor in office. The gentleman from California (Mr. ligence that policymakers require. Therefore, Donald John Trump by SCHIFF) and the gentleman from Cali- At the same time, H.R. 3494 ensures causing such harm to the society of the fornia (Mr. NUNES) each will control 30 close oversight by Congress, rejecting United States is unfit to be President minutes. the funding of legacy IC programs with and warrants impeachment, trial, and The Chair recognizes the gentleman overseas contingency operation re- removal from office. from California (Mr. SCHIFF). sources, or OCO, funding; and requir- The SPEAKER pro tempore. Under Mr. SCHIFF. Mr. Chairman, I yield ing, for the first time, the submission rule IX, a resolution offered from the myself as much time as I may con- to the intelligence committees of de- floor by a Member other than the ma- sume. tailed information on unfunded IC pro- jority leader or the minority leader as Along the wall in the upper lobby of grams. a question of the privileges of the the CIA headquarters building is a Another provision authored by Rep- House has immediate precedence only large picture of the head and torch of resentative WELCH calls for more infor- at a time designated by the Chair with- the Statue of Liberty accompanied by mation in the IC’s budget for counter- in 2 legislative days after the resolu- the following words: ‘‘We are the Na- terrorism matters to be released to the tion is properly noticed. -

Camp Chapman Attack

Camp Chapman attack The Camp Chapman attack was a suicide attack by of those killed had already approached the bomber to Humam Khalil Abu-Mulal al-Balawi against the Central search him, whereas others killed were standing some dis- Intelligence Agency facility inside Forward Operating tance away.[6] At least 13 intelligence officers were within Base Chapman on December 30, 2009. FOB Chapman 50 feet of al-Balawi when the bomb went off.[7] is located near the eastern Afghanistan city of Khost, After the attack, the base was secured and 150 mostly which is about 10 miles northwest of the border with Afghan workers were detained and held incommunicado Pakistan. One of the main tasks of the CIA personnel sta- for three days.[8][9] The attack was a major setback for tioned at the base was to provide intelligence supporting [1] the intelligence agency’s operations in Afghanistan and drone attacks against targets in Pakistan. Seven Amer- Pakistan.[10][11][12] It was the second largest single-day ican CIA officers and contractors, an officer of Jordan's loss in the CIA’s history, after the 1983 United States intelligence service, and an Afghan working for the CIA Embassy bombing in Beirut, Lebanon, which killed eight were killed when al-Balawi detonated a bomb sewn into CIA officers.[11] The incident suggested that al-Qaeda a vest he was wearing. Six other American CIA officers might not be as weakened as previously thought.[13] were wounded. The bombing was the most lethal attack against the CIA in more than 25 years. -

Appendix C Memorials and Recognitions

Appendix C Memorials and Recognitions Facilities, Scholarships, Memorials, and other public recognitions for or dedicated to the fallen from the Officer Candidate School Classes, Fort Knox, Kentucky, 1965 – 1968. In addition, included recognition for our two living Medal of Honor recipients and the only other Ft. Knox OCS graduate known to have been killed while serving the country. Note: National Memorials like The Wall and the numerous state Vietnam Veterans Memorials, including the ones in the state capitols, are not listed. The official state Home of Record (HOR) for each man is included in the Roll of Honor (Appendix A) for those who wish to visit state memorials. National memorials also exist for many military organizations such as the 25th Infantry Division at Schofield Barracks HI, the 173rd Airborne Brigade at Columbus GA and the comprehensive online “data bases” for the VHPA which includes detailed information on more than four dozen of our KIA and is used as a reference in the Coffelt Data Base of Vietnam Casualties 1LT William Curry Ahouse, Class 5-67 F2: KIA 8 Jun 68, Vietnam The Academy of Richmond County (name embossed): Richmond GA The Augusta Georgia and CSRA (Central Savannah River Area) Vietnam Veterans Memorial (name inscribed): Augusta GA 1LT Jerry Allen Ashburn, Class 31-67 C2: KIA 17 Jun 69, Vietnam. Awarded the National Order of Vietnam 5th Class CPT Ronald Daniel Briggs, Class 20-67 E2: MIA 6 Feb 69, Vietnam Group Burial Memorial: Remains recovered in 1996, identified in 2005. Arlington National Cemetery, Arlington, -

The Value of Film and Television in Teaching Human Intelligence

Journal of Strategic Security Volume 8 Number 3 Volume 8, No. 3, Special Issue Fall 2015: Intelligence: Analysis, Article 5 Tradecraft, Training, Education, and Practical Application Setauket to Abbottabad: The Value of Film and Television in Teaching Human Intelligence Keith Cozine Ph.D. St. John's University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/jss pp. 80-92 Recommended Citation Cozine, Keith Ph.D.. "Setauket to Abbottabad: The Value of Film and Television in Teaching Human Intelligence." Journal of Strategic Security 8, no. 3 (2015) : 80-92. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5038/1944-0472.8.3.1467 Available at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/jss/vol8/iss3/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Open Access Journals at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Strategic Security by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Setauket to Abbottabad: The Value of Film and Television in Teaching Human Intelligence Abstract Espionage is often referred to as the world’s second oldest profession, and human intelligence is the oldest collection discipline. When many people think of espionage the images that often come to mind are fictional characters such as Jason Bourne or James Bond. Human intelligence encompasses much more than “secret agents” using their “toys” to collect top-secret information. Teaching human intelligence within an academic setting can be difficult because of the clandestine nature of tradecraft and sources of intelligence. Ironically, it is television and film that brought us Bourne and Bond that can also aid in the teaching of the variety of issues and concepts important to the study of human intelligence. -

CIA at WAR Studies in Intelligence Is a Quarterly Publication Prepared Primarily for the Use of US Government Offcials

Dedicated to the families of CIA offcers, past and present. Authors Ursula M. Wilder Toni L. Hiley Tracey P. Peter Garfeld Project Leader CIA Museum Curator Graphic Designer Photographer The authors thank the numerous dedicated people whose time and talents made this publication possible. All contributors were united by their pride in CIA’s history and mission and by their desire to support and thank our families. The outcome is, in the best tradition of CIA, the result of many hands and many hearts giving without expectation of rewards other than those that are found in service to others. CIA AT WAR WAR CIA AT Studies in Intelligence is a quarterly publication prepared primarily for the use of US government offcials. This book is a supplementary issue. Its format, coverage, and content, as with all issues of Studies, are designed to meet the requirements of US government offcials. All statements of fact, opinion, or analysis expressed in this publication are those of the authors. They do not necessarily refect offcial positions or views of the Central Intelligence Agency or any other US government entity, past or present. Nothing in the contents should be construed as asserting or implying US government endorsement of factual statements, interpretations, or recommendations. Issues of Studies often contain material that is protected by copyright. Such items are marked and attributed and should not be reproduced and widely disseminated without permission. Editorial Policy Studies in Intelligence is produced by the Center for the Study of Intelligence. CSI’s core mission is to enhance the operational, analytical, and administrative effectiveness of the CIA and the Intelligence Community by creating knowledge and understanding of the lessons of the past, by assessing current practices, and by preparing intelligence offcers and their organizations for future challenges. -

Inside the Cia In-House Design Director Glenn John Arnowitz Recently Got a Rare Look Inside the Central Intelligence Agency’S Design Department

BY GLENN JOHN ARNOWITZ VANCOUVER | APRIL 2008 ANTICIPATING THREATS IN A CONNECTED WORLD CREATING NETWORKING POSSIBILITIES DI Design Center/MPG 420589AI 2-08 IN-HOUSE ISSUES INSIDE THE CIA In-house design director Glenn John Arnowitz recently got a rare look inside the Central Intelligence Agency’s design department. Here’s the scoop on this top-secret institution. When I received an e-mail last March from Mark books and magazines—and was inviting me to the Hernandez, who said he was with the CIA, I became CIA headquarters in Washington, DC, to speak to his concerned: department of designers, cartographers and web and “Dear Mr. Arnowitz, interactive specialists on inspiration, motivation and We’ve been following you for some time …” creativity. I was both flattered and honored to receive Hmmm. I’ve never cheated on my taxes, I’ve never this offer and immediately accepted it. But I have to been arrested and, as far as I know, I’m not wanted admit, during the months leading up to the visit, my in any of the 50 states. As I continued to read on, my paranoia reared its ugly head again as my wife and I fears and paranoia subsided. I soon discovered that became convinced our phones were being tapped and Hernandez is the art director of the Central Intel- we were being watched. “Did you notice that man sit- ligence Agency’s Office of Policy Support, where for ting in the car parked across the street?” I asked my the past 23 years he’s been a key member of this elite wife. -

Advocates for Harvard ROTC . Telephone: (978) 443-9532 11 Munnings Drive Email: [email protected] Sudbury, MA 01776 5 June 2020

Advocates for Harvard ROTC . Telephone: (978) 443-9532 11 Munnings Drive Email: [email protected] Sudbury, MA 01776 5 June 2020 From: Captain Paul E. Mawn USN (Ret.) To: Advocates for Harvard ROTC Subject: Post WW2 military veterans among Harvard alumni (H-1920 to present) Harvard graduates have a long proud history of serving as warriors in the United States military. During the Korean War, 60% of the Harvard classes served in the US military but only 23% of the class of 1963 served in the US military (note: the % of military veterans in other classes since the Korean War have not yet been validated. I suspect the % of veterans in the late 1950’s & early 1960’s were similar to 1963 participation level but was slightly higher during the late 1960’s and early 1970’s as the Vietnam War heated up. Due to the anti- military policies of the Harvard administration and the expulsion of on campus ROTC programs, the mid 1970’s saw a precipitous drop in the number of patriotic Harvard graduates who elected to do something beyond their own self-interest by serve our country in the US military. Thus over the past 4 decades, less than 1% of Harvard graduates are military veterans of whom about half were commissioned through the ROTC programs based at MIT. However recently, Harvard has recently taken a proactive positive posture towards the US military. As result, ROTC participation at Harvard has been steadily increasing with over 1.3% the Harvard class of 2023 serving as midshipmen or cadets and a significantly higher % accepted for the class of 2024.