What Foreign Diplomats Need to Know About Canada: Personal Reflections

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Canada-U.S. Relations

Canada-U.S. Relations Updated February 10, 2021 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov 96-397 SUMMARY 96-397 Canada-U.S. Relations February 10, 2021 The United States and Canada typically enjoy close relations. The two countries are bound together by a common 5,525-mile border—“the longest undefended border in the world”—as Peter J. Meyer well as by shared history and values. They have extensive trade and investment ties and long- Specialist in Latin standing mutual security commitments under NATO and North American Aerospace Defense American and Canadian Command (NORAD). Canada and the United States also cooperate closely on intelligence and Affairs law enforcement matters, placing a particular focus on border security and cybersecurity initiatives in recent years. Ian F. Fergusson Specialist in International Although Canada’s foreign and defense policies usually are aligned with those of the United Trade and Finance States, disagreements arise from time to time. Canada’s Liberal Party government, led by Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, has prioritized multilateral efforts to renew and strengthen the rules- based international order since coming to power in November 2015. It expressed disappointment with former President Donald Trump’s decisions to withdraw from international organizations and accords, and it questioned whether the United States was abandoning its global leadership role. Cooperation on international issues may improve under President Joe Biden, who spoke with Prime Minister Trudeau in his first call to a foreign leader and expressed interest in working with Canada to address climate change and other global challenges. The United States and Canada have a deep economic partnership, with approximately $1.4 billion of goods crossing the border each day in 2020. -

Public Art Guide

DOWNTOWN REGINA PUBLIC ART GUIDE Downtown Regina Public Art Guide 1 JOSH GOFF & DANNY FERNANDEZ Tiki Room Wall (2010) on front cover 2323 11th AVE. 1 “Tiki Room Wall” has been one of the most vibrant pieces of downtown Regina art since the summer of 2010. The mural was completed over the course of two weeks, with Goff and Fernandez each putting in fourteen hour days. Creating the piece necessitated the use of a skyjack which placed the artists three full building storeys above the ground. “Tiki Room Wall”, like many of Goff and Fernandez’s pieces, is done in spray paint. Goff and Fernandez’s intention in creat- ing the piece was to bring colour, optimism, and a sense of something different to the lives of those who live, work, shop, and dine downtown, as he feels that colour, particularly the absence of it, affects people’s moods. ROB BOS ^ Tornado Scribble (2012) 1845 CORNWALL ST. 2 Bos’ piece commemorating the 100th anniversary of the Regina tornado shows how the written line destroys the blankness of the page to create symbols that can be read and understood. Meaning thus comes from this initial destruc- tive gesture and then manifests itself in an abstract form. These lines can be used to both communicate and obscure meaning, such as when a word is scribbled out and replaced by another. “Tornado Scribble” suggests the multiple new meanings put forth by the destruction and loss incurred by the tornado, and how they alter perception and memory. The piece is 25 feet high and 12 feet wide, and is made from lazer cut aluminum. -

MUS LISTE CHANSONS-9 Juillet P1

MUSIQUE Le Québec de Charlebois à Arcade Fire MUSIC Quebec: From Charlebois to Arcade Fire Crédits partiels des chansons et des productions audiovisuelles Partial credits for songs and audiovisual productions L’INSOLENCE DE LA JEUNESSE Welcome Soleil, Jim et Bertrand, © 1976 INSOLENCE OF YOUTH (Bertrand Gosselin) Comme un fou, Harmonium, © 1976 Le Ya Ya, Joël Denis, © 1965 (Serge Fiori, Michel Normandeau) (Morris Levy, Clarence Lewis, adaptation française / french La maudite machine, Octobre, © 1973 adaptation: Joël Denis) (Pierre Flynn) Le p’tit popy, Michel Pagliaro (Les Chanceliers), © 1967 La bourse ou la vie, Contraction, © 1974 (Lindon Oldham, Dan Penn) (Georges-Hébert Germain, Robert Lachapelle, Yves Laferrière, Tu veux revenir, Gerry Boulet (Les Gants blancs), © 1967 Christiane Robichaud) (Robert Feldman, Gerald Goldstein, Richard Gottehrer) Les saigneurs, Opus 5, © 1976 Tout peut recommencer, Ginette Reno, © 1963 (Luc Gauthier) (Jerry Reed) Beau Bummage, Aut’chose, © 1976 Ces bottes sont faites pour marcher, Dominique Michel, © 1966 (Jacques Racine, Jean-François St-Georges, Lucien Francoeur) (Lee Hazlewood) Dear Music, Mahogany Rush, © 1974 (Frank Marino) Yéyé partout, Jenny Rock, Jeunesse Oblige (Radio-Canada), Ma patrie est à terre, Offenbach, © 1975 1967 (Roger Belval, Gérald Boulet, Jean Gravel, Pierre Harel, Michel Ton amour a changé ma vie, Les Classels, Copain Copain Lamothe) , Plume Latraverse, © 1978 (Radio-Canada), 1964 Le rock and roll du grand flanc mou (Michel Latraverse) , 20 ans Express (Radio- Le short trop court interdit à Verdun Closer Together, The Box, © 1987 Canada), 27 juillet 1963 / July 27, 1963 (Guy Pisapia, Jean-Pierre Brie, Luc Papineau, Jean Marc Pisapia) Cash City, Luc De Larochellière, © 1990 RÊVER DE MONDES DIFFÉRENTS (Luc De Larochellière, Marc Pérusse) DREAMING OF OTHER WORLDS Les Yankees, Richard Desjardins, © 1992 (Richard Desjardins) J’ai souvenir encore, Claude Dubois, © 1964 Modern Man, Arcade Fire, © 2010 (Claude Dubois) (Edwin F. -

Munk School of Global Affairs & Public Policy

Munk School of Global Affairs & Public Policy Annual Report 2019–20 2 munk school of global affairs & public policy About the Munk School Table of Contents About the Munk School ...................................... 2 Student Programs ..............................................12 Research & Ideas ................................................36 Public Engagement ............................................72 Supporting Excellence ......................................88 Faculty and Academic Directors .......................96 Named Chairs and Professorships....................98 Munk School Fellows .........................................99 Donors ...............................................................101 1 munk school of global affairs & public policy AboutAbout the theMunk Munk School School About the Munk School The Munk School of Global Affairs & Public Policy is a leader in interdisciplinary research, teaching and public engagement. Established in 2010 through a landmark gift by Peter and Melanie Munk, the School is home to more than 50 centres, labs and teaching programs, including the Asian Institute; Centre for European, Russian, and Eurasian Studies; Centre for the Study of the United States; Centre for the Study of Global Japan; Trudeau Centre for Peace, Conflict and Justice and the Citizen Lab. With more than 230 affiliated faculty and more than 1,200 students in our teaching programs — including the professional Master of Global Affairs and Master of Public Policy degrees — the Munk School is known for world-class faculty, research leadership and as a hub for dialogue and debate. Visit munkschool.utoronto.ca to learn more. 2 munk school of global affairs & public policy About the Munk School About the Munk School 3 munk school of global affairs & public policy 2019–20 annual report 3 About the Munk School Our Founding Donors In 2010, Peter and Melanie Munk made a landmark gift to the University of Toronto that established the (then) Munk School of Global Affairs. -

Powerful & Influential in Government & Politics in 2016

MODERNIZING MILITARY LAW/PRIME MINISTER’S QP/BILL CASEY 100TOP most POWERFUL & INFLUENTIAL IN GOVERNMENT & POLITICS IN 2016 ROSEMARY BARTON >> JUSTIN TRUDEAU KATIE TELFORD BILL MORNEAU MICHAEL FERGUSON CATHERINE MCKENNA HARJIT SAJJAN BOB FIFE IS CANADA SIMON KENNEDY REALLY MÉLANIE JOLY BRIAN BOHUNICKY BACK? ROLAND PARIS DIPLOMATS ARE READYING FOR CANADA’S BIGGER BRUCE HEYMAN ROLE IN THE WORLD $6.99 Winter 2016 CHANTAL HÉBERT Power & Infl uence hilltimes.com/powerinfl uence RONA AMBROSE MENDING FENCES ANNA GAINEY THE PUBLIC SERVICE’S RELATIONSHIP AND MORE WITH A NEW GOVERNMENT CANADA’S NON-COMBAT SHIPBUILDING PARTNER Thyssenkrupp Marine Systems Canada Building Canada’s Maritime Future through the Government of Canada’s National Shipbuilding Procurement Strategy (NSPS). www.seaspan.com CONTENTS FEATURES IS CANADA REALLY BACK? 18 The Liberal government has pledged to renew Canadian diplomacy and Winter 2016 “recommit to supporting international peace operations with the United Nations.” Vol. 5 No. 1 What’s in store for Canada’s foreign affairs portfolio? PUBLIC SERVICE 180 22 Over the last decade, public servants have felt like implementers of commands as opposed to creators and innovators of ideas or solutions. They will have to retrain themselves to think differently. THE TOP 100 MOST POWERFUL & INFLUENTIAL PEOPLE IN GOVERNMENT AND POLITICS 2016 24 26 54 35 47 COLUMNS CONNECTING THE DOTS: Trade and health care ethics 12 INSIDE THE POLITICAL TRENCH: A Prime Minister’s QP? 13 CANADA’S BIG CHALLENGES: Small businesses and the Canadian economy -

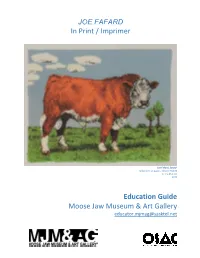

JOE FAFARD in Print / Imprimer

JOE FAFARD In Print / Imprimer Joe Fafard, Sonny! Silkscreen on paper, edition 75/150 37.2 x 46.6 cm 1979 Education Guide Moose Jaw Museum & Art Gallery [email protected] TABLE OF CONTENTS CURRICULUM CONNECTIONS 1 PART I - INTRODUCTION 2-7 1. EXHIBITION ESSAY 2-4 2. INTRODUCTION TO: a. THE ARTIST 5 b. ART MEDIA 5-6 c. INSPIRATION 7 PART II – INTRODUCTION TO PRINTMAKING 8-9 1. BUILDING AN ART VOCABULARY 9 PART III – PRE-TOUR 9-14 1. FORMS OF PRINTMAKING 9 a. EMBOSSING 9-10 b. ETCHING 10-11 c. LITHOGRAPHY 11 d. SERIOGRAPH 12 e. SILKSCREEN 12-13 f. WOODBLOCK 13 2. ACTIVITY 14 PART IV – THE TOUR 14-18 1. FOCUS ATTENTION 14 2. INTRODUCE THE EXHIBITION 15 3. QUESTIONING STRATEGY 15 a. FIRST IMPRESSIONS 16 b. ANALYSIS 16-17 c. INTERPRETATION 17-18 d. CONTEXT 18 e. SYNTHESIS 18 PART V – ACTIVITIES 19-26 1. INTRODUCTION: HOW TO PRINT WITH A BRAYER (ROLLER) 19 2. MONOPRINTS WITH TIN FOIL 19-20 3. MONOPRINTS WITH GLASS OR PLEXIGLASS 21 4. LINOCUT PRINTS USING FOAM PLATES 22-23 5. LINOCUT PRINTS USING EASY BLOCKS 24-25 6. EMBOSS PRINTING 25-26 PART VI – MORE INFORMATION 27-48 1. BIOGRAPHY OF JOE FAFARD 27-28 2. CURRICULUM VITAE OF JOE FAFARD 28-38 3. LIST OF WORKS 39-44 4. RESOURCE MATERIAL 45 5. OSAC TOUR SCHEDULE 46 6. OSAC INFORMATION 47-48 PART VII – ADDITIONAL RESOURCES 49-52 1. ADDITIONAL HANDS-ON ACTIVITIES 50 2. PRE-TOUR ACTIVITY – QUESTIONS 51 3. KIT SAMPLES 52 Curriculum Connections Social Studies Farming in Saskatchewan Our Community Saskatchewan Artists Visual Arts Printmaking 1 | P a g e EDUCATION GUIDE – MJM&AG – OSAC TOUR Joe Fafard In Print/Imprimer PART I – Introduction 1. -

No Ordinary Joe the Extraordinary Art of Joe Fafard

volume 23, no. 2 fall/winter 2011 The University of Regina Magazine No ordinary Joe The extraordinary art of Joe Fafard The 2011 Alumni Crowning Achievement Award recipients (left to right) Outstanding Young Alumnus Award recipient Rachel Mielke BAdmin’03; Ross Mitchell BSc’86(High Honours), MSc’89, Award for Professional Achievement; Eric Grimson, Lifetime Achievement Award; Dr. Robert and Norma Ferguson Award for Outstanding Service recipient Twyla Meredith BAdmin’82; Bernadette Kollman BAdmin’86, Distinguished Humanitarian and Community Service Award recipient. Photo by Don Hall, University of Regina Photography Department. Degrees | fall/winter 2011 1 On September 16, 2011 have endured for 30 years. The Founders’ Dinner in February the University of Regina would the University lost a great University was the first post- that he could not attend. have been without Lloyd Barber. administrator, colleague and secondary institution in Canada Despite being tethered to an For 14 years he gave as much friend. Dr. Lloyd Barber was to establish such relationships. oxygen tank and having to of himself to the University the second president and Upon his retirement in 1990, make his way around his home of Regina as anyone has ever vice-chancellor of the University Barber was presented with a on an electric scooter, Barber given. I can’t say for sure if he of Regina and shepherded bronze sculpture of himself entertained us for hours with fully appreciated the mark that it through its early, shaky sculpted by the subject of stories from his days in the he left on the place. I wonder if independent days, under mostly our cover story – artist Joe president’s office. -

Celebrating the Right Brain Snail-Mail Gossip • a 21St-Century Safari • the Donors’ Report

trinityTRINITY ALUMNI MAGAZINE FALL 2009 celebrating the right brain snail-mail gossip • a 21st-century safari • the donors’ report revTrinity_fall'09.indd 1 10/6/09 5:11:45 PM provost’smessage Learned and Beautiful Trinity has always been about more than setting and surpassing academic expectations The start of the school year is always exciting and exhausting: ecstasy that accompany academic endeavour, and the final line new faces appear, old faces reappear, and the College looks its of the College song celebrates the attainments of the women of best after a summer of repair and refurbishment. The new back St. Hilda’s as doctae atque bellae (learned and beautiful). Both field is a wonderful new asset that I hope will be heavily used, and make it clear that here, scholarship alone is not enough. the quad, now wireless, has in recent weeks seen students loung- Even if our Aberdeen-born founder seems suitably stern ing and labouring. The official opening of the green roof on in his portraits, John Strachan was not immune to relaxation. Cartwright Hall, largely funded by the generosity of the Scotch blood, after all, flowed in his veins, sometimes in ap- class of ’58, takes place this month, and the re-roofing of the parently undiluted quantities. At one point, the Bishop, having Larkin Building to accommodate solar panels, primarily been told that one of his clergy was too fond of the bottle, is funded by students, is well underway. Frosh week was by all said to have replied: “Tut, tut: That is a most extravagant way accounts a great success, and at Matriculation we welcomed to buy whisky; I always buy mine by the barrel.” (Presumably the incoming class of ’13, and honoured three of our own: the same barrel he appears to be wearing in the painting that Donald Macdonald, Margaret MacMillan, and Richard Alway. -

Joe Fafard Autopsie D’Une Controverse Joe Fafard Anatomy of a Controversy Greg Beatty

Document généré le 28 sept. 2021 22:53 Espace Sculpture Joe Fafard Autopsie d’une controverse Joe Fafard Anatomy of a Controversy Greg Beatty Art public Public Art Numéro 48, été 1999 URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/9521ac Aller au sommaire du numéro Éditeur(s) Le Centre de diffusion 3D ISSN 0821-9222 (imprimé) 1923-2551 (numérique) Découvrir la revue Citer cet article Beatty, G. (1999). Joe Fafard : autopsie d’une controverse / Joe Fafard: Anatomy of a Controversy. Espace Sculpture, (48), 14–19. Tous droits réservés © Le Centre de diffusion 3D, 1999 Ce document est protégé par la loi sur le droit d’auteur. L’utilisation des services d’Érudit (y compris la reproduction) est assujettie à sa politique d’utilisation que vous pouvez consulter en ligne. https://apropos.erudit.org/fr/usagers/politique-dutilisation/ Cet article est diffusé et préservé par Érudit. Érudit est un consortium interuniversitaire sans but lucratif composé de l’Université de Montréal, l’Université Laval et l’Université du Québec à Montréal. Il a pour mission la promotion et la valorisation de la recherche. https://www.erudit.org/fr/ JOE FAFARD ART PUBLIC PUBLIC ART Autopsie d'une controverse Anatomy oP a Controversy GREG BEATTY vec la diminution de l'aide gouvernementale aux arts, les ven ith declining government support for the arts, private sales tes au secteur privé et les commandes publiques deviennent de and commissions are becoming increasingly important. But A plus en plus importantes, même si des pièges existent, comme pitfalls exist, as the following story demonstrates. In December en témoigne l'histoire qui suit. -

Forty-Ninth Parallel Constitutionalism: How Canadians Invoke American Constitutional Traditions

FORTY-NINTH PARALLEL CONSTITUTIONALISM: HOW CANADIANS INVOKE AMERICAN CONSTITUTIONAL TRADITIONS I. INTRODUCTION While a debate over citing foreign law rages in America, Canadian constitutional discourse references the United States with frequency, familiarity, and no second thoughts. This is nothing new. After all, Canada’s original constitutional framework was in some ways a reac- tion against American constitutionalism.1 Similarly, the drafters of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms,2 passed in 1982, took care- ful account of the American Bill of Rights.3 Nevertheless, today’s burgeoning of comparative constitutionalism invites a closer and more structured look at the role America plays in Canadian constitutional discourse. As comparative constitutionalists strive for methodological discipline,4 setting out criteria for how and when foreign constitutional experience should be employed, the Cana- dian example, with its rich references to American constitutionalism, serves as a useful case study.5 This Note proposes a framework for understanding the ways in which Canadian constitutional discourse invokes American constitu- tionalism. Canadian political and legal actors, it suggests, use Ameri- can sources in three ways: as a model to follow, as an anti-model to avoid, and as a dialogical resource for reflecting on Canada’s own con- stitutional identity.6 Each of these positions, moreover, is situated ––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– 1 See PETER H. RUSSELL, CONSTITUTIONAL ODYSSEY 12 (3d ed. 2004) (“[The] basic con- stitutional assumptions [at the time of Confederation] were those of Burke and the Whig constitu- tional settlement of 1689 rather than of Locke and the American Constitution.”); id. at 23 (de- scribing how the Fathers of Confederation saw American federalism as “thoroughly flawed”). -

Gaby – Maître Du Portrait Celebrities of Yesteryear Captured in Stunning Photos

Press release | For immediate distribution GABY – MAÎTRE DU PORTRAIT CELEBRITIES OF YESTERYEAR CAPTURED IN STUNNING PHOTOS Montreal, September 15, 2014 - Anne Hébert, Félix Leclerc, Dominique Michel, Louis Armstrong, Jean Cocteau, Jayne Mansfield… At the peak of his career, Québécois photog- rapher Gabriel Desmarais (Gaby) had the priv- ilege of photographing the hottest Canadian and international stars. Starting today, more than 90 large-format portraits taken from the 1940s to the 1980s will be on display in Quartier des Spectacles: outdoors, on Promenade des Artistes and De Maisonneuve Blvd. (until November 16), and indoors at the Anne Hébert, 1962 Félix Leclerc , 1951 Dominique Michel, 1951 Grande Bibliothèque (until June 7, 2015). © Ronald Desmarais © Ronald Desmarais © Ronald Desmarais Collections BAnQ Collections BAnQ Collections BAnQ “With Gaby, maître du portrait, we are not only showcasing an exceptional artist, we are ensuring that several audiences will have access to his works. Thanks to our collaboration with the Quartier des Spectacles Partnership, thousands of people will have the chance to see Gaby’s exceptional photographs during their strolls through downtown or when they visit the Grande Bibliothèque,” said Christiane Barbe, Chief Executive Officer of Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec (BAnQ). “Gaby’s photos are a treasure, and we consider Louis Armstrong, 1967 Jayne Mansfield, 1957 Jean Cocteau, 1955 © Ronald Desmarais / Getty Images © Ronald Desmarais / Getty Images © Ronald Desmarais / Getty Images it -

The Roots of French Canadian Nationalism and the Quebec Separatist Movement

Copyright 2013, The Concord Review, Inc., all rights reserved THE ROOTS OF FRENCH CANADIAN NATIONALISM AND THE QUEBEC SEPARATIST MOVEMENT Iris Robbins-Larrivee Abstract Since Canada’s colonial era, relations between its Fran- cophones and its Anglophones have often been fraught with high tension. This tension has for the most part arisen from French discontent with what some deem a history of religious, social, and economic subjugation by the English Canadian majority. At the time of Confederation (1867), the French and the English were of almost-equal population; however, due to English dominance within the political and economic spheres, many settlers were as- similated into the English culture. Over time, the Francophones became isolated in the province of Quebec, creating a densely French mass in the midst of a burgeoning English society—this led to a Francophone passion for a distinct identity and unrelent- ing resistance to English assimilation. The path to separatism was a direct and intuitive one; it allowed French Canadians to assert their cultural identities and divergences from the ways of the Eng- lish majority. A deeper split between French and English values was visible before the country’s industrialization: agriculture, Ca- Iris Robbins-Larrivee is a Senior at the King George Secondary School in Vancouver, British Columbia, where she wrote this as an independent study for Mr. Bruce Russell in the 2012/2013 academic year. 2 Iris Robbins-Larrivee tholicism, and larger families were marked differences in French communities, which emphasized tradition and antimaterialism. These values were at odds with the more individualist, capitalist leanings of English Canada.