Arxiv:1809.03080V1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Observing Galaxies in Pegasus 01 October 2015 23:07

Observing galaxies in Pegasus 01 October 2015 23:07 Context As you look towards Pegasus you are looking below the galactic plane under the Orion spiral arm of our galaxy. The Perseus-Pisces supercluster wall of galaxies runs through this constellation. It stretches from RA 3h +40 in Perseus to 23h +10 in Pegasus and is around 200 million light years away. It includes the Pegasus I group noted later this document. The constellation is well placed from mid summer to late autumn. Pegasus is a rich constellation for galaxy observing. I have observed 80 galaxies in this constellation. Relatively bright galaxies This section covers the galaxies that were visible with direct vision in my 16 inch or smaller scopes. This list will therefore grow over time as I have not yet viewed all the galaxies in good conditions at maximum altitude in my 16 inch scope! NGC 7331 MAG 9 This is the stand out galaxy of the constellation. It is similar to our milky way. Around it are a number of fainter NGC galaxies. I have seen the brightest one, NGC 7335 in my 10 inch scope with averted vision. I have seen NGC 7331 in my 25 x 100mm binoculars. NGC 7814 - Mag 10 ? Not on observed list ? This is a very lovely oval shaped galaxy. By constellation Page 1 NGC 7332 MAG 11 / NGC 7339 MAG 12 These galaxies are an isolated bound pair about 67 million light years away. NGC 7339 is the fainter of the two galaxies at the eyepiece. I have seen NGC 7332 in my 25 x 100mm binoculars. -

7.5 X 11.5.Threelines.P65

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-19267-5 - Observing and Cataloguing Nebulae and Star Clusters: From Herschel to Dreyer’s New General Catalogue Wolfgang Steinicke Index More information Name index The dates of birth and death, if available, for all 545 people (astronomers, telescope makers etc.) listed here are given. The data are mainly taken from the standard work Biographischer Index der Astronomie (Dick, Brüggenthies 2005). Some information has been added by the author (this especially concerns living twentieth-century astronomers). Members of the families of Dreyer, Lord Rosse and other astronomers (as mentioned in the text) are not listed. For obituaries see the references; compare also the compilations presented by Newcomb–Engelmann (Kempf 1911), Mädler (1873), Bode (1813) and Rudolf Wolf (1890). Markings: bold = portrait; underline = short biography. Abbe, Cleveland (1838–1916), 222–23, As-Sufi, Abd-al-Rahman (903–986), 164, 183, 229, 256, 271, 295, 338–42, 466 15–16, 167, 441–42, 446, 449–50, 455, 344, 346, 348, 360, 364, 367, 369, 393, Abell, George Ogden (1927–1983), 47, 475, 516 395, 395, 396–404, 406, 410, 415, 248 Austin, Edward P. (1843–1906), 6, 82, 423–24, 436, 441, 446, 448, 450, 455, Abbott, Francis Preserved (1799–1883), 335, 337, 446, 450 458–59, 461–63, 470, 477, 481, 483, 517–19 Auwers, Georg Friedrich Julius Arthur v. 505–11, 513–14, 517, 520, 526, 533, Abney, William (1843–1920), 360 (1838–1915), 7, 10, 12, 14–15, 26–27, 540–42, 548–61 Adams, John Couch (1819–1892), 122, 47, 50–51, 61, 65, 68–69, 88, 92–93, -

An H-Alpha Survey Aiming at the Detection of Extraplanar Diffuse

Astronomy & Astrophysics manuscript no. (will be inserted by hand later) An Hα survey aiming at the detection of extraplanar diffuse ionized gas in halos of edge–on spiral galaxies ⋆ II. The Hα survey atlas and catalog J. Rossa ⋆⋆1,2 and R.–J. Dettmar1 1 Astronomisches Institut, Ruhr–Universit¨at Bochum, D–44780 Bochum, Germany e-mail: [email protected], [email protected] 2 Space Telescope Science Institute, 3700 San Martin Drive, Baltimore, MD 21218, U.S.A. (present address) Received 14 February 2003 / Accepted 6 May 2003 Abstract. In this second paper on the investigation of extraplanar diffuse ionized gas in nearby edge–on spiral galaxies we present the actual results of the individual galaxies of our Hα imaging survey. A grand total of 74 galaxies have been studied, including the 9 galaxies of a recently studied sub–sample (Rossa & Dettmar 2000). 40.5% of all studied galaxies reveal extraplanar diffuse ionized gas, whereas in 59.5% of the survey galaxies no extraplanar diffuse ionized gas could be detected. The average distances of this extended emission above the galactic midplane range from 1–2 kpc, while individual filaments in a few galaxies reach distances of up to |z| ∼ 6 kpc. In several cases a pervasive layer of ionized gas was detected, similar to the Reynolds layer in our Milky Way, while other galaxies reveal only extended emission locally. The morphology of the diffuse ionized gas is discussed for each galaxy and is compared with observations of other important ISM constituents in the context of the disk–halo connection, in those cases where published results were available. -

Making a Sky Atlas

Appendix A Making a Sky Atlas Although a number of very advanced sky atlases are now available in print, none is likely to be ideal for any given task. Published atlases will probably have too few or too many guide stars, too few or too many deep-sky objects plotted in them, wrong- size charts, etc. I found that with MegaStar I could design and make, specifically for my survey, a “just right” personalized atlas. My atlas consists of 108 charts, each about twenty square degrees in size, with guide stars down to magnitude 8.9. I used only the northernmost 78 charts, since I observed the sky only down to –35°. On the charts I plotted only the objects I wanted to observe. In addition I made enlargements of small, overcrowded areas (“quad charts”) as well as separate large-scale charts for the Virgo Galaxy Cluster, the latter with guide stars down to magnitude 11.4. I put the charts in plastic sheet protectors in a three-ring binder, taking them out and plac- ing them on my telescope mount’s clipboard as needed. To find an object I would use the 35 mm finder (except in the Virgo Cluster, where I used the 60 mm as the finder) to point the ensemble of telescopes at the indicated spot among the guide stars. If the object was not seen in the 35 mm, as it usually was not, I would then look in the larger telescopes. If the object was not immediately visible even in the primary telescope – a not uncommon occur- rence due to inexact initial pointing – I would then scan around for it. -

Herschel II Lista Di Herschel II

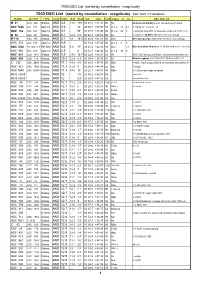

Herschel II Lista di Herschel II Oltre i 400 Pagina 1 Gabriele Franzo Herschel II Chart R.A. Dec. Size Size Object OTHER Type Con. Mag. SUBR Class NGC Description No. ( h m ) ( o ' ) max min 61 NGC 23 UGC 89 GALXY PEG 00 09.9 +25 55 12 13 2.5 m 1.6 m SBa 3 S st + neb 109 NGC 24 ESO 472-16 GALXY SCL 00 09.9 -24 58 11,6 13,7 6.1 m 1.4 m Sc vF,cL,mE,gbm 85 NGC 125 UGC 286 GALXY PSC 00 28.8 +02 50 12,1 13 1.8 m 1.6 m Sa Ring vF,S,bM,D * sp 85 NGC 151 NGC 153 GALXY CET 00 34.0 -09 42 11,6 13,4 3.8 m 1.6 m SBbc pF,pL,lE 90 degrees,vglbM 109 NGC 175 NGC 171 GALXY CET 00 37.4 -19 56 12,2 13,5 2.1 m 1.9 m SBab pB,pL,E,gbM,r 85 NGC 198 UGC 414 GALXY PSC 00 39.4 +02 48 13,1 13,4 1.1 m 1.1 m Sc F,S,vgbM 37 NGC 206 G+C+N AND 00 40.5 +40 44 99,9 99,9 Pec vF,vL,mE 0 degrees 61 NGC 214 UGC 438 GALXY AND 00 41.5 +25 30 12,3 13,1 1.9 m 1.5 m SBc pF,pS,gvlbM,R 85 NGC 217 MCG - 2- 2- 85 GALXY CET 00 41.6 -10 01 13.5p 99,9 2.7 m 0.6 m Sa F,S,lE 90 degrees,glbM 61 NGC 315 UGC 597 GALXY PSC 00 57.8 +30 21 11,2 13,2 3 m 2.5 m E-SO pB,pL,R,gbM,* 9 nf 3' 85 NGC 337 MCG - 1- 3- 53 GALXY CET 00 59.8 -07 35 11,6 13,3 3 m 1.8 m SBcd pF,L,E,glbM,* 10 f 21 sec 84 NGC 357 MCG - 1- 3- 81 GALXY CET 01 03.4 -06 20 12 13,4 2.5 m 1.7 m SBO-a F,S,iR,sbM,* 14 nf 20'' 60 NGC 410 UGC 735 GALXY PSC 01 11.0 +33 09 11,5 12,7 2.3 m 1.8 m SB0 pB,pL,nf of 2 84 NGC 428 UGC 763 GALXY CET 01 12.9 +00 59 11,5 14,1 4 m 2.9 m Scp F,L,R,bM,er 60 NGC 499 IC 1686 GALXY PSC 01 23.2 +33 28 12,1 12,8 1.7 m 1.3 m E-SO pB,pL,R,3rd of 3 60 NGC 513 UGC 953 GALXY AND 01 24.4 +33 48 12,9 11,1 0.7 m -

DSO List V2 Current

7000 DSO List (sorted by name) 7000 DSO List (sorted by name) - from SAC 7.7 database NAME OTHER TYPE CON MAG S.B. SIZE RA DEC U2K Class ns bs Dist SAC NOTES M 1 NGC 1952 SN Rem TAU 8.4 11 8' 05 34.5 +22 01 135 6.3k Crab Nebula; filaments;pulsar 16m;3C144 M 2 NGC 7089 Glob CL AQR 6.5 11 11.7' 21 33.5 -00 49 255 II 36k Lord Rosse-Dark area near core;* mags 13... M 3 NGC 5272 Glob CL CVN 6.3 11 18.6' 13 42.2 +28 23 110 VI 31k Lord Rosse-sev dark marks within 5' of center M 4 NGC 6121 Glob CL SCO 5.4 12 26.3' 16 23.6 -26 32 336 IX 7k Look for central bar structure M 5 NGC 5904 Glob CL SER 5.7 11 19.9' 15 18.6 +02 05 244 V 23k st mags 11...;superb cluster M 6 NGC 6405 Opn CL SCO 4.2 10 20' 17 40.3 -32 15 377 III 2 p 80 6.2 2k Butterfly cluster;51 members to 10.5 mag incl var* BM Sco M 7 NGC 6475 Opn CL SCO 3.3 12 80' 17 53.9 -34 48 377 II 2 r 80 5.6 1k 80 members to 10th mag; Ptolemy's cluster M 8 NGC 6523 CL+Neb SGR 5 13 45' 18 03.7 -24 23 339 E 6.5k Lagoon Nebula;NGC 6530 invl;dark lane crosses M 9 NGC 6333 Glob CL OPH 7.9 11 5.5' 17 19.2 -18 31 337 VIII 26k Dark neb B64 prominent to west M 10 NGC 6254 Glob CL OPH 6.6 12 12.2' 16 57.1 -04 06 247 VII 13k Lord Rosse reported dark lane in cluster M 11 NGC 6705 Opn CL SCT 5.8 9 14' 18 51.1 -06 16 295 I 2 r 500 8 6k 500 stars to 14th mag;Wild duck cluster M 12 NGC 6218 Glob CL OPH 6.1 12 14.5' 16 47.2 -01 57 246 IX 18k Somewhat loose structure M 13 NGC 6205 Glob CL HER 5.8 12 23.2' 16 41.7 +36 28 114 V 22k Hercules cluster;Messier said nebula, no stars M 14 NGC 6402 Glob CL OPH 7.6 12 6.7' 17 37.6 -03 15 248 VIII 27k Many vF stars 14.. -

Peg – Objektauswahl NGC Teil 1

Peg – Objektauswahl NGC Teil 1 NGC 0001 NGC 0042 NGC 7074 NGC 7146 NGC 7206 NGC 7270 NGC 7303 NGC 7321 NGC 0002 NGC 0052 NGC 7078 NGC 7147 NGC 7207 NGC 7271 NGC 7305 NGC 7323 NGC 0009 NGC 7033 NGC 7085 NGC 7149 NGC 7212 NGC 7272 NGC 7311 NGC 7324 NGC 0014 NGC 7034 NGC 7094 NGC 7156 NGC 7217 NGC 7275 NGC 7312 NGC 7328 Teil 2 NGC 0015 NGC 7042 NGC 7101 NGC 7159 NGC 7224 NGC 7280 NGC 7315 NGC 7331 NGC 0016 NGC 7043 NGC 7102 NGC 7177 NGC 7236 NGC 7283 NGC 7316 NGC 7332 Teil 3 NGC 0022 NGC 7053 NGC 7113 NGC 7190 NGC 7237 NGC 7286 NGC 7317 NGC 7335 NGC 0023 NGC 7056 NGC 7132 NGC 7193 NGC 7241 NGC 7290 NGC 7318 NGC 7336 Teil 4 NGC 0026 NGC 7066 NGC 7137 NGC 7194 NGC 7244 NGC 7291 NGC 7319 NGC 7337 NGC 0041 NGC 7068 NGC 7138 NGC 7195 NGC 7253 NGC 7292 NGC 7320 NGC 7339 Sternbild- Zur Objektauswahl: Nummer anklicken Übersicht Zur Übersichtskarte: Objekt in Aufsuchkarte anklicken Zum Detailfoto: Objekt in Übersichtskarte anklicken Peg – Objektauswahl NGC Teil 2 NGC 7340 NGC 7360 NGC 7375 NGC 7411 NGC 7435 NGC 7463 NGC 7479 NGC 7509 Teil 1 NGC 7342 NGC 7362 NGC 7376 NGC 7413 NGC 7436 NGC 7464 NGC 7485 NGC 7511 NGC 7343 NGC 7363 NGC 7383 NGC 7414 NGC 7437 NGC 7465 NGC 7487 NGC 7512 NGC 7345 NGC 7366 NGC 7385 NGC 7415 NGC 7439 NGC 7466 NGC 7489 NGC 7514 NGC 7346 NGC 7367 NGC 7386 NGC 7420 NGC 7442 NGC 7467 NGC 7490 NGC 7515 NGC 7347 NGC 7369 NGC 7387 NGC 7427 NGC 7448 NGC 7468 NGC 7495 NGC 7516 Teil 3 NGC 7348 NGC 7370 NGC 7389 NGC 7430 NGC 7451 NGC 7469 NGC 7497 NGC 7519 NGC 7353 NGC 7372 NGC 7390 NGC 7431 NGC 7454 NGC 7473 NGC 7500 NGC 7523 Teil -

Dave Mitsky's Monthly Celestial Calendar

Dave Mitsky’s Monthly Celestial Calendar January 2010 ( between 4:00 and 6:00 hours of right ascension ) One hundred and five binary and multiple stars for January: Omega Aurigae, 5 Aurigae, Struve 644, 14 Aurigae, Struve 698, Struve 718, 26 Aurigae, Struve 764, Struve 796, Struve 811, Theta Aurigae (Auriga); Struve 485, 1 Camelopardalis, Struve 587, Beta Camelopardalis, 11 & 12 Camelopardalis, Struve 638, Struve 677, 29 Camelopardalis, Struve 780 (Camelopardalis); h3628, Struve 560, Struve 570, Struve 571, Struve 576, 55 Eridani, Struve 596, Struve 631, Struve 636, 66 Eridani, Struve 649 (Eridanus); Kappa Leporis, South 473, South 476, h3750, h3752, h3759, Beta Leporis, Alpha Leporis, h3780, Lallande 1, h3788, Gamma Leporis (Lepus); Struve 627, Struve 630, Struve 652, Phi Orionis, Otto Struve 517, Beta Orionis (Rigel), Struve 664, Tau Orionis, Burnham 189, h697, Struve 701, Eta Orionis, h2268, 31 Orionis, 33 Orionis, Delta Orionis (Mintaka), Struve 734, Struve 747, Lambda Orionis, Theta-1 Orionis (the Trapezium), Theta-2 Orionis, Iota Orionis, Struve 750, Struve 754, Sigma Orionis, Zeta Orionis (Alnitak), Struve 790, 52 Orionis, Struve 816, 59 Orionis, 60 Orionis (Orion); Struve 476, Espin 878, Struve 521, Struve 533, 56 Persei, Struve 552, 57 Persei (Perseus); Struve 479, Otto Struve 70, Struve 495, Otto Struve 72, Struve 510, 47 Tauri, Struve 517, Struve 523, Phi Tauri, Burnham 87, Xi Tauri, 62 Tauri, Kappa & 67 Tauri, Struve 548, Otto Struve 84, Struve 562, 88 Tauri, Struve 572, Tau Tauri, Struve 598, Struve 623, Struve 645, Struve -

DSO List V2 Current

7000 DSO List (sorted by constellation - magnitude) 7000 DSO List (sorted by constellation - magnitude) - from SAC 7.7 database NAME OTHER TYPE CON MAG S.B. SIZE RA DEC U2K Class ns bs SAC NOTES M 31 NGC 224 Galaxy AND 3.4 13.5 189' 00 42.7 +41 16 60 Sb Andromeda Galaxy;Local Group;nearest spiral NGC 7686 OCL 251 Opn CL AND 5.6 - 15' 23 30.1 +49 08 88 IV 1 p 20 6.2 H VIII 69;12* mags 8...13 NGC 752 OCL 363 Opn CL AND 5.7 - 50' 01 57.7 +37 40 92 III 1 m 60 9 H VII 32;Best in RFT or binocs;Ir scattered cl 70* m 8... M 32 NGC 221 Galaxy AND 8.1 12.4 8.5' 00 42.7 +40 52 60 E2 Companion to M31; Member of Local Group M 110 NGC 205 Galaxy AND 8.1 14 19.5' 00 40.4 +41 41 60 SA0 M31 Companion;UGC 426; Member Local Group NGC 272 OCL 312 Opn CL AND 8.5 - 00 51.4 +35 49 90 IV 1 p 8 9 NGC 7662 PK 106-17.1 Pln Neb AND 8.6 5.6 17'' 23 25.9 +42 32 88 4(3) 14 Blue Snowball Nebula;H IV 18;Barnard-cent * variable? NGC 956 OCL 377 Opn CL AND 8.9 - 8' 02 32.5 +44 36 62 IV 1 p 30 9 NGC 891 UGC 1831 Galaxy AND 9.9 13.6 13.1' 02 22.6 +42 21 62 Sb NGC 1023 group;Lord Rosse drawing shows dark lane NGC 404 UGC 718 Galaxy AND 10.3 12.8 4.3' 01 09.4 +35 43 91 E0 Mirach's ghost H II 224;UGC 718;Beta AND sf 6' IC 239 UGC 2080 Galaxy AND 11.1 14.2 4.6' 02 36.5 +38 58 93 SBa In NGC 1023 group;vsBN in smooth bar;low surface br NGC 812 UGC 1598 Galaxy AND 11.2 12.8 3' 02 06.9 +44 34 62 Sbc Peculiar NGC 7640 UGC 12554 Galaxy AND 11.3 14.5 10' 23 22.1 +40 51 88 SBbc H II 600;nearly edge on spiral MCG +08-01-016 Galaxy AND 12 - 1.0' 23 59.2 +46 53 59 Face On MCG +08-01-018 -

October 12Th 2019 October 2019 7:00Pm at the Herrett Center for Arts & Science College of Southern Idaho

Snake River Skies The Newsletter of the Magic Valley Astronomical Society www.mvastro.org Membership Meeting MVAS President’s Message October 2019 Saturday, October 12th 2019 7:00pm at the Herrett Center for Arts & Science College of Southern Idaho. The month of September started with the moon, both India’s valiant effort that fell Public Star Party follows at the short in successfully landing a rover, and images from members of MVAS of the Centennial Observatory second brightest light in the sky. Those images were part of a flurry of activity started by the late August star party at the Oregon Trail Overlook at the Hagerman Club Officers Fossil Beds National Monument. As I write this, we still don’t know if the weather will Robert Mayer, President allow us to go to the Craters of the Moon National Monument and land more [email protected] pictures for the last weekend of September, but hopefully images and Hagerman will pop up again for us in October. Gary Leavitt, Vice President [email protected] First, this month’s meeting will feature a tradition and a required event. We’ll again put on the annual MVAS Year-in-Pictures show, but before that, we will hold our Dr. Jay Hartwell, Secretary annual officers’ election. Please contact me about either pictures or nominations by th Friday, Oct. 11. Our meeting itself will be the next day, Saturday, Oct. 12 , at 7 p.m. Jim Tubbs, Treasurer / ALCOR in the Rick Allen Room of the Herrett Center. [email protected] 208-404-2999 Later in the month, we hope to return to Hagerman, this time for a public viewing on th Oct. -

A Abell 21, 20–21 Abell 37, 164 Abell 50, 264 Abell 262, 380 Abell 426, 402 Abell 779, 51 Abell 1367, 94 Abell 1656, 147–148

Index A 308, 321, 360, 379, 383, Aquarius Dwarf, 295 Abell 21, 20–21 397, 424, 445 Aquila, 257, 259, 262–264, 266–268, Abell 37, 164 Almach, 382–383, 391 270, 272, 273–274, 279, Abell 50, 264 Alnitak, 447–449 295 Abell 262, 380 Alpha Centauri C, 169 57 Aquila, 279 Abell 426, 402 Alpha Persei Association, Ara, 202, 204, 206, 209, 212, Abell 779, 51 404–405 220–222, 225, 267 Abell 1367, 94 Al Rischa, 381–382, 385 Ariadne’s Hair, 114 Abell 1656, 147–148 Al Sufi, Abdal-Rahman, 356 Arich, 136 Abell 2065, 181 Al Sufi’s Cluster, 271 Aries, 372, 379–381, 383, 392, 398, Abell 2151, 188–189 Al Suhail, 35 406 Abell 3526, 141 Alya, 249, 255, 262 Aristotle, 6 Abell 3716, 297 Andromeda, 327, 337, 339, 345, Arrakis, 212 Achird, 360 354–357, 360, 366, 372, Auriga, 4, 291, 425, 429–430, Acrux, 113, 118, 138 376, 380, 382–383, 388, 434–436, 438–439, 441, Adhara, 7 391 451–452, 454 ADS 5951, 14 Andromeda Galaxy, 8, 109, 140, 157, Avery’s Island, 13 ADS 8573, 120 325, 340, 345, 351, AE Aurigae, 435 354–357, 388 B Aitken, Robert, 14 Antalova 2, 224 Baby Eskimo Nebula, 124 Albino Butterfly Nebula, 29–30 Antares, 187, 192, 194–197 Baby Nebula, 399 Albireo, 70, 269, 271–272, 379 Antennae, 99–100 Barbell Nebula, 376 Alcor, 153 Antlia, 55, 59, 63, 70, 82 Barnard 7, 425 Alfirk, 304, 307–308 Apes, 398 Barnard 29, 430 Algedi, 286 Apple Core Nebula, 280 Barnard 33, 450 Algieba, 64, 67 Apus, 173, 192, 214 Barnard 72, 219 Algol, 395, 399, 402 94 Aquarii, 335 Barnard 86, 233, 241 Algorab, 98, 114, 120, 136 Aquarius, 295, 297–298, 302, 310, Barnard 92, 246 Allen, Richard Hinckley, 5, 120, 136, 320, 324–325, 333–335, Barnard 114, 260 146, 188, 258, 272, 286, 340–341 Barnard 118, 260 M.E. -

Revised Shapley Ames.Pdf

A REVISED SHAPLEY-AMES CATALOG OF BRIGHT GALAXIES The Las Canspanas ridge iii Chile during the last stages of construction of the dome for the du Pont 2.5-meter reflector. The du Pout instrument is at the north end of'thr long escarpment. The Swope 1-meter reflector is in the left foreground. Photu courtesy oi'R, J. Bruuito ; 1*<7*J-. A Revised Shapley-Ames Catalog of Bright Galaxies Containing Data on Magnitudes, Types, and Redshifts for Galaxies in the Original Harvard Survey, Updated to Summer 1980. Also Contains a Selection of Photographs Illustrating the Luminosity Classification and a List of Additional Galaxies that Satisfy the Magnitude Limit of the Original Catalog. Allan Sandage and G. A. Tammann CARNEGIE INSTITUTION OF WASHINGTON PUBLICATION 635 WASHINGTON, D.C. • 198 1 ISBN:0-87U79-<i52-:i Libran oi'CongrrssCatalog Card No. 80-6H146 (JompoMtion. Printing, and Binding by Mmden-Stinehour. Inr. ('<»p\ritiht C ]'M\, (Jariit'^it* Institution nf Washington ACKNOWLEDGMENTS We are indebted to Miss B. Flach and Mrs. R. C. Kraan- Korteweg for their help in compiling part of the data. We also owe special thanks to Basil Katem for his large effort in de- termining revised coordinates by measurement of National Geo- graphic-Palomar Sky Survey prints and Uppsala Schmidt plates for most of the listed galaxies, and to John Bedke for his skill in reproducing the photographs. We are especially grateful to R. J. Brucato for his important help in obtaining the most recent plates at Las Campanas. We greatly appreciate the help of several observers for provid- ing prepublication redshift data.