Part Ii; Self Defense and the New Law of the Sea Regimes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Page 1 of 7 Location the Nation of Libya Is Located in North Africa And

Libya Location The nation of Libya is located in North Africa and covers approximately one million seven hundred fifty square kilometers, which is slightly larger than the United State’s Alaska. It is one of the largest countries in Africa. Libya lies in the geographic coordinates 25°N and 17°E. It is bordered in the north by the Mediterranean Sea and by Niger and Chad in the south. Libya’s western border connects to Algeria and Tunisia, and connects to Egypt and Sudan in the east. Geography The highest point in Libya is the Bikku Bitti, also known as Bette Peak, which stands at seven thousand four hundred and thirty eight feet at its highest point. It is located in the Tibesti Mountains in southern Libya near the Chadian border. The Sahara, an immense North African desert, covers most of Libya. Much of the country’s land consists of barren, rock-strewn plains and sand sea, with flat to underlying plains, plateaus, and depressions. Two small areas of hills ascend in the northwest and northeast, and the Tibesti mountains rise near the southern border. There are no permanent rivers or streams in Libya. The coastline is sunken near the center by the Gulf of Sidra, where barren desert reaches the Mediterranean Sea. Libya is divided into three natural regions. The first and largest, to the east of the Gulf of Sidra, is Cyrenaica, which occupies the plateau of Jabal al Akhdar. The majority of the area of Cyrenaica is covered with sand dunes, especially along the border with Egypt. -

Africa Command: U.S

Order Code RL34003 Africa Command: U.S. Strategic Interests and the Role of the U.S. Military in Africa Updated July 6, 2007 Lauren Ploch Analyst in African Affairs Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Africa Command: U.S. Strategic Interests and the Role of the U.S. Military in Africa Summary On February 6, 2007, the Bush Administration announced its intention to create a new unified combatant command, U.S. Africa Command or AFRICOM, to promote U.S. national security objectives in Africa and its surrounding waters. U.S. military involvement on the continent is currently divided among three commands: U.S. European Command (EUCOM), U.S. Central Command (CENTCOM), and U.S. Pacific Command (PACOM). As envisioned by the Administration, the command’s area of responsibility (AOR) would include all African countries except Egypt. In recent years, analysts and U.S. policymakers have noted Africa’s growing strategic importance to U.S. interests. Among those interests are Africa’s role in the Global War on Terror and the potential threats posed by ungoverned spaces; the growing importance of Africa’s natural resources, particularly energy resources; and ongoing concern for the continent’s many humanitarian crises, armed conflicts, and more general challenges, such as the devastating effect of HIV/AIDS. In 2006, Congress authorized a feasibility study on the creation of a new command for Africa. As defined by the Department of Defense (DOD), AFRICOM’s mission will be to promote U.S. strategic objectives by working with African states and regional organizations to help strengthen stability and security in the region through improved security capability, military professionalization, and accountable governance. -

Full Spring 2004 Issue the .SU

Naval War College Review Volume 57 Article 1 Number 2 Spring 2004 Full Spring 2004 Issue The .SU . Naval War College Follow this and additional works at: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/nwc-review Recommended Citation Naval War College, The .SU . (2004) "Full Spring 2004 Issue," Naval War College Review: Vol. 57 : No. 2 , Article 1. Available at: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/nwc-review/vol57/iss2/1 This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Naval War College Review by an authorized editor of U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Naval War College: Full Spring 2004 Issue N A V A L W A R C O L L E G E NAVAL WAR COLLEGE REVIEW R E V I E W Spring 2004 Volume LVII, Number 2 Spring 2004 Spring N ES AV T A A L T W S A D R E C T I O N L L U E E G H E T R I VI IBU OR A S CT MARI VI Published by U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons, 2004 1 Color profile: Disabled Composite Default screen Naval War College Review, Vol. 57 [2004], No. 2, Art. 1 Cover A Landsat-7 image (taken on 27 July 2000) of the Lena Delta on the Russian Arctic coast, where the Lena River emp- ties into the Laptev Sea. The Lena, which flows northward some 2,800 miles through Siberia, is one of the largest rivers in the world; the delta is a pro- tected wilderness area, the largest in Rus- sia. -

Libya: the First Totally Privatized War in Modern History

LIBYA: THE FIRST TOTALLY PRIVATIZED WAR IN MODERN HISTORY A report by Javier Martín Only Turkey has officially sent troops, THE FIRST although not for combat. And the LNA has a structure that could bring it closer to that of a regular armed force, with uniforms and TOTALLY a clear consolidated chain of command. The rest of the combatants are native PRIVATIZED militias and local and foreign PMSCs contracted by both rival governments in a sort of outsourcing that offers multiple WAR IN advantages, especially for foreign powers. MODERN COSTS, WITHDRAWALS HISTORY AND ACCOUNTABILITY Javier Martín The existence of mercenaries and PMSCs is nothing new, true. They have existed since ancient times, but their pattern has changed in the last forty years. From the Alsa Masa, the anti-communist forces A victim of chaos and war since March created in the Philippines in 1984 during 2011, when NATO -pushed by France- the presidency of the controversial decided to intervene and contribute with its Ferdinand Marcos, to the armed groups missiles to the victory of the different rebel "the awakening", promoted by the United factions over the long dictatorship of States in 2006 to fight the insurgency in Muammar Al Gaddafi, Libya has been since the Sunni regions of Iraq, to the Janjaweed then the scene of an armed conflict that in tribes in the Darfur region of Sudan, the ten years has evolved from a rudimentary Community Guards in Mexico and even the civil war conditioned by the terrorism of LAGs in Spain, the militias and jihadist ideology to a highly sophisticated paramilitary organizations associated with multinational conflict, becoming the first governments have been a planetary totally privatized armed conflict in constant since at least the end of World contemporary history. -

11 · the Culmination of Greek Cartography in Ptolemy

11 · The Culmination of Greek Cartography in Ptolemy o. A. w. DILKE WITH ADDITIONAL MATERIAL SUPPLIED BY THE EDITORS By the time of Marinus of Tyre (fl. A.D. 100) and Clau about his work remain unanswered. Little is known dius Ptolemy (ca. A.D. 90-168), Greek and Roman in about Ptolemy the man, and neither his birthplace nor fluences in cartography had been fused to a considerable his dates have been positively established.4 Moreover, extent into one tradition. There is a case, accordingly, in relation to the cartographic component in his writings, for treating them as a history of one already unified we must remember that no manuscript earlier than the stream of thought and practice. Here, however, though twelfth century A.D. has come down to us, and there is we accept that such a unity exists, the discussion is fo no adequate modern translation and critical edition of cused on the cartographic contributions of Marinus and the Geography.5 Perhaps most serious of all for the stu Ptolemy, both writing in Greek within the institutions dent of mapping, however, is the whole debate about of Roman society. Both men owed much to Roman the true authorship and provenance of the general and sources of information and to the extension ofgeograph regional maps that accompany the several versions of ical knowledge under the growing empire: yet equally, the Byzantine manuscripts (pp. 268-74 below). AI- in the case of Ptolemy especially, they represent a cul mination as well as a final synthesis of the scientific tradition in Greek cartography that has been traced through a succession of writers in the previous three 1. -

American Bombing of Libya: an International Legal Analysis Gregory Francis Intoccia

Case Western Reserve Journal of International Law Volume 19 | Issue 2 1987 American Bombing of Libya: An International Legal Analysis Gregory Francis Intoccia Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/jil Part of the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Gregory Francis Intoccia, American Bombing of Libya: An International Legal Analysis, 19 Case W. Res. J. Int'l L. 177 (1987) Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/jil/vol19/iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Journals at Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Case Western Reserve Journal of International Law by an authorized administrator of Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. AMERICAN BOMBING OF LIBYA: AN INTERNATIONAL LEGAL ANALYSIS by Gregory FrancisIntoccia* I. INTRODUCTION The United States-initiated aerial bombing of targets inside the borders of the Libyan Arab Jamahiriyah which took place on April 15, 1986,1 was met with substantial and immediate criticism by the world commu- nity.2 The positive reaction from the U.S. congress3 and the American public4 was not shared by much of the world. Arab nations denounced the American action,5 as did the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries. 6 In meetings of the UN Security Council,7 countries de- nouncing the raid outnumbered those which supported it.8 Even Ameri- can allies responded with heated rhetoric.9 However, in the weeks which followed the bombing, world opinion softened significantly. Cooperation became evident amongst the Western Allies. -

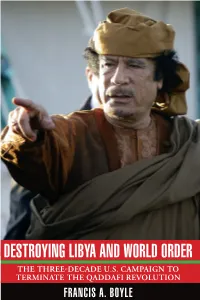

Destroying Libya and World Order

DESTROYING LIBYA DESTROYING LIBYA Political Science • International Law AN D t took three decades for the United States government—spanning and WOR working assiduously over five different presidential administrations (Reagan, Bush I, Clinton, Bush II, and Obama)—to terminate the 1969 Qaddafi Revolution, seize control over Libya’s oil fields, and dismantle LD its Jamahiriya system. This book tells the story of what happened, why O it happened, and what was both wrong and illegal with that from the perspective R I D of an international law professor and lawyer who tried for over three decades to ER stop it. Francis Boyle provides a comprehensive history and critique of American TERMINA foreign policy toward Libya from when the Reagan administration came to power Three-Deca THE in January of 1981 up to the 2011 NATO war on Libya that ultimately achieved the US goal of regime change, and beyond. He sets the record straight on the T series of military conflicts and crises between the United States and Libya over the E T Gulf of Sidra, exposing the Reagan administration’s fraudulent claims of Libyan HE QA instigation of international terrorism put forward over his eight years in office. D E U.S. E U.S. Boyle reveals the inside story behind the Lockerbie bombing cases against the DD United States and the United Kingdom that he filed at the World Court for Colonel AFI Qaddafi acting upon his advice—and the unjust resolution of those disputes. C AMPAIGN AMPAIGN R Deploying standard criteria of international law, Boyle analyzes and debunks EVOL the UN R2P “responsibility to protect” doctrine and its immediate predecessor, “humanitarian intervention”. -

THE Law of the Sea and MEDITERRANEAN Security

MEDITERRANEAN PAPER SERIES 2010 THE LAW OF THE SEA AND MEDITERRANEAN SECURITY Natalino Ronzitti © 2010 The German Marshall Fund of the United States. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the German Marshall Fund of the United States (GMF). Please direct inquiries to: The German Marshall Fund of the United States 1744 R Street, NW Washington, DC 20009 T 1 202 683 2650 F 1 202 265 1662 E [email protected] This publication can be downloaded for free at http://www.gmfus.org/publications/index.cfm. Limited print copies are also available. To request a copy, send an e-mail to [email protected]. GMF Paper Series The GMF Paper Series presents research on a variety of transatlantic topics by staff, fellows, and partners of the German Marshall Fund of the United States. The views expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of GMF. Comments from readers are welcome; reply to the mailing address above or by e-mail to [email protected]. About GMF The German Marshall Fund of the United States (GMF) is a non-partisan American public policy and grantmaking institu- tion dedicated to promoting better understanding and cooperation between North America and Europe on transatlantic and global issues. GMF does this by supporting individuals and institutions working in the transatlantic sphere, by convening leaders and members of the policy and business communities, by contributing research and analysis on transatlantic topics, and by pro- viding exchange opportunities to foster renewed commitment to the transatlantic relationship. -

![Collection: Mandel, Judyt: Files Folder Title: [Terrorism – Libya Public Diplomacy – Libya Under Qadhafi: a Pattern of Aggression] Box: 91721](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9939/collection-mandel-judyt-files-folder-title-terrorism-libya-public-diplomacy-libya-under-qadhafi-a-pattern-of-aggression-box-91721-4649939.webp)

Collection: Mandel, Judyt: Files Folder Title: [Terrorism – Libya Public Diplomacy – Libya Under Qadhafi: a Pattern of Aggression] Box: 91721

Ronald Reagan Presidential Library Digital Library Collections This is a PDF of a folder from our textual collections. Collection: Mandel, Judyt: Files Folder Title: [Terrorism – Libya Public Diplomacy – Libya Under Qadhafi: A Pattern of Aggression] Box: 91721 To see more digitized collections visit: https://reaganlibrary.gov/archives/digital-library To see all Ronald Reagan Presidential Library inventories visit: https://reaganlibrary.gov/document-collection Contact a reference archivist at: [email protected] Citation Guidelines: https://reaganlibrary.gov/citing National Archives Catalogue: https://catalog.archives.gov/ Libya Under Qadhafi: A Pattern of Aggression Contents Page Libya Under Qadhafi: A Pattern of Aggression Character of Libyan Policy Libyan Involvement in Terrorism Libyan Links to Middle East Radicals 2 Libyan Terrorism Against the United States 2 Radicalism in the Arab World 2 Involvement in Sub-Saharan Africa 4 Meddling in Latin America and the Caribbean 4 South and Southeast Asia 5 The Erosion of International Norms 5 Chronology of Libyan Support for Terrorism 1980-85 7 The Abu Nida! Group 13 Introduction 13 Background 13 Current Operations and Trends 14 iii Libya U oder Qadhafi: A Pattern of Aggression Character of Libyan Policy establishment in their country. Qadhafi generally uses Mu'ammar Qadhafi seized power in a military coup Libyans for antiexile operations; for other types of in 1969. Since then he has forcibly sought to remake attacks he tends to employ surrogates or mercenaries. Libyan society according to his own revolutionary precepts. Qadhafi's ambitions are not confined within The Libyan Government in 1980 began a concerted Libya's borders, however. He fancies himself a leader effort to assassinate anti-Qadhafi exiles. -

PART 11 the Diamond Anniversary Decade 1981–1990

UNITED STATES NAVAL AVIATION 1910–1995 331 PART 11 The Diamond Anniversary Decade 1981–1990 The eighth decade of Naval Aviation was character- Naval Aviation’s involvement in international ized by a buildup of its forces, the rise of world-wide events—major highlights of the 1980s—began with acts of terrorism and Naval Aviation’s involvement in Iran and the continuing hostage crisis, 1979–1981. response to the various crises throughout the world. Libyan operations in 1981, 1986 and 1989 demonstrat- The decade began with American Embassy person- ed Naval Aviation’s air-to-air and strike capabilities. In nel being held as hostages in Iran. As had been the 1983, a carrier and amphibious task force took part in case since the Cold War began, carriers were on sta- Operation Urgent Fury and the re-establishment of tion in response to the crisis. The latter part of the democracy in the Caribbean island of Grenada. 1970s had seen an increase in the number of carrier Operations in and around Lebanon kept Naval deployments to the Indian Ocean. In the 1980s that Aviation occupied during the mid-1980s. Responding trend was increased and strengthened. Undoubtedly, to hijacking and terrorism in the Mediterranean basin this was the result of the ongoing and increasing prob- was an ongoing requirement for most of the 1980s. lems in the Middle East, eastern Africa and the sub- The other hot spot for Naval Aviation was the Persian continent of Asia. Gulf and the Iran-Iraq war. Naval Aviation was During the 1980s, Naval Aviation saw a resurgence involved in numerous periods of short-lived combat in its strength and capabilities. -

The Gulf of Sidra Incident of 1981: a Study of the Lawfulness of Peacetime Aerial Engagements

The Gulf of Sidra Incident of 1981: A Study of the Lawfulness of Peacetime Aerial Engagements Steven R. Ratnert I. Problem On August 19, 1981, U.S. F-14 fighter aircraft engaged in combat with two Libyan Sukhoi-22 fighters above the Gulf of Sidra, approximately sixty miles off the coast of Libya.' By the end of the encounter, both Libyan planes had been destroyed and one Libyan pilot killed. According to Libyan assertions, one of its fighters destroyed one of the U.S. F-14s, but this contention was denied by the United States. Although Libyan aircraft had on previous occasions fired upon U.S. military planes, 2 the Gulf of Sidra incident marked the first time that U:S. aircraft returned fire. The Gulf of Sidra incident indicates that aerial rules of engagement formulated by individual states are subject to an identifiable and widely accepted norm. This norm requires that, in peacetime, military aircraft attempt to avoid the first use of force during potentially hostile en- counters with the aircraft of another state. The norm permits a first use of force only when necessary for immediate unit or national self-defense, and then usually only after giving warning. Rules of engagement (ROE) is the general term used to describe the "directives that a government may establish to delineate the circum- stances and limitations under which its own naval, ground, and air forces will initiate and/or continue combat engagement with enemy forces. ' 3 With reference to the particular form of ROE to be discussed in this Study, the practice followed by most states appears to have consisted in t A.B., Princeton University, 1982; J.D. -

Seapower and Space: from the Dawn of the Missile Age Tonet-Centric Warfare, William C

Naval War College Review Volume 57 Article 21 Number 1 Winter 2004 Seapower and Space: From the Dawn of the Missile Age toNet-centric Warfare, William C. Martel Follow this and additional works at: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/nwc-review Recommended Citation Martel, William C. (2004) "Seapower and Space: From the Dawn of the Missile Age toNet-centric Warfare,," Naval War College Review: Vol. 57 : No. 1 , Article 21. Available at: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/nwc-review/vol57/iss1/21 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Naval War College Review by an authorized editor of U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BOOK REVIEWS 139 Martel: Seapower and Space: From the Dawn of the Missile Age toNet-centri Beginning in the 1970s with territorial naval forces conduct navigation, claims that the Gulf of Sidra was actu- communication, reconnaissance, and ally within Libyan internal waters, targeting. The reality is that modern Qaddafi had plotted a collision course military forces depend almost entirely with the United States. For over two de- on platforms in space to know where cades he attempted to use Libya’s oil they are and to communicate with wealth to undermine moderate govern- friendly forces, as well as to know the ments in the Middle East and Africa, location of enemy forces and use that sought weapons of mass destruction, information to destroy them.