NINE BATTLES of ONLINE GROCERY Part 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Response: Just Eat Takeaway.Com N. V

NON- CONFIDENTIAL JUST EAT TAKEAWAY.COM Submission to the CMA in response to its request for views on its Provisional Findings in relation to the Amazon/Deliveroo merger inquiry 1 INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND 1. In line with the Notice of provisional findings made under Rule 11.3 of the Competition and Markets Authority ("CMA") Rules of Procedure published on the CMA website, Just Eat Takeaway.com N.V. ("JETA") submits its views on the provisional findings of the CMA dated 16 April 2020 (the "Provisional Findings") regarding the anticipated acquisition by Amazon.com BV Investment Holding LLC, a wholly-owned subsidiary of Amazon.com, Inc. ("Amazon") of certain rights and minority shareholding of Roofoods Ltd ("Deliveroo") (the "Transaction"). 2. In the Provisional Findings, the CMA has concluded that the Transaction would not be expected to result in a substantial lessening of competition ("SLC") in either the market for online restaurant platforms or the market for online convenience groceries ("OCG")1 on the basis that, as a result of the Coronavirus ("COVID-19") crisis, Deliveroo is likely to exit the market unless it receives the additional funding available through the Transaction. The CMA has also provisionally found that no less anti-competitive investors were available. 3. JETA considers that this is an unprecedented decision by the CMA and questions whether it is appropriate in the current market circumstances. In its Phase 1 Decision, dated 11 December 20192, the CMA found that the Transaction gives rise to a realistic prospect of an SLC as a result of horizontal effects in the supply of food platforms and OCG in the UK. -

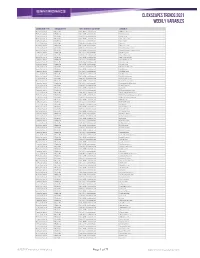

Clickscapes Trends 2021 Weekly Variables

ClickScapes Trends 2021 Weekly VariableS Connection Type Variable Type Tier 1 Interest Category Variable Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment 1075koolfm.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment 8tracks.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment 9gag.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment abs-cbn.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment aetv.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment ago.ca Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment allmusic.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment amazonvideo.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment amphitheatrecogeco.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment ancestry.ca Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment ancestry.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment applemusic.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment archambault.ca Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment archive.org Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment artnet.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment atomtickets.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment audible.ca Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment audible.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment audiobooks.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment audioboom.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment bandcamp.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment bandsintown.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment barnesandnoble.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment bellmedia.ca Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment bgr.com Home Internet Website Arts & Entertainment bibliocommons.com -

Food and Tech August 13

⚡️ Love our newsletter? Share the ♥️ by forwarding it to a friend! ⚡️ Did a friend forward you this email? Subscribe here. FEATURED Small Farmers Left Behind in Covid Relief, Hospitality Industry Unemployment Remains at Depression-Era Levels + More Our round-up of this week's most popular business, tech, investment and policy news. Pathways to Equity, Diversity + Inclusion: Hiring Resource - Oyster Sunday This Equity, Diversity + Inclusion Hiring Resource aims to help operators to ensure their tables are filled with the best, and most equal representation of talent possible – from drafting job descriptions to onboarding new employees. 5 Steps to Move Your Food, Beverage or Hospitality Business to Equity Jomaree Pinkard, co-founder and CEO of Hella Cocktail Co, outlines concrete steps businesses and investors can take to foster equity in the food, beverage and hospitality industries. Food & Ag Anti-Racism Resources + Black Food & Farm Businesses to Support We've compiled a list of resources to learn about systemic racism in the food and agriculture industries. We also highlight Black food and farm businesses and organizations to support. CPG China Says Frozen Chicken Wings from Brazil Test Positive for Virus - Bloomberg The positive sample appears to have been taken from the surface of the meat, while previously reported positive cases from other Chinese cities have been from the surface of packaging on imported seafood. Upcycled Molecular Coffee Startup Atomo Raises $9m Seed Funding - AgFunder S2G Ventures and Horizons Ventures co-led the round. Funding will go towards bringing the product to market. Diseased Chicken for Dinner? The USDA Is Considering It - Bloomberg A proposed new rule would allow poultry plants to process diseased chickens. -

Ahmedabad Maninagar Shop No

Ahmedabad Maninagar Shop No - 1/A, 1St Floor, Rudraksh, Nr. Fire Station, Krishnabaug, Kanakaria-Maninagar Road, Pin Code - 380008 Prahlad Nagar- Corporate Road Shop No.2, Ashirwad Paras, Corporate Road, Prahlad Nagar, Pin Code - 380015 Satellite Rd- Gulmohar Mall Shop No.05, Ground Floor, Gulmohar Park Mall, Satellite Road, Pin Code - 380015 Shyamal Cross Rd Shop No G-13, Shangrila Arcade, Nr. Shayamal Cross Road, Satellite, Pin Code - 380015 University Road- Next to CCD Acumen, Ground Floor, University Road, Next To CCD, Pin Code - 380015 Vastrapur- Alpha 1 Mall Hypercity, Alpha One Mall, Vastrapur, Pin Code - 380054 Vastrapur- Himalaya Mall Shop No. 105, Ground Floor, Himalaya Mall, Memnagar, Pin Code - 380059 Bengaluru Bengaluru - Indiranagar Ground Floor, Next To CCD, MSK Plaza, Defense Colony, 100 Ft Road, Indiranagar, HAL 2Nd Stage Pin Code - 560038 Bengaluru - Jaya Nagar Ground Floor, Rajlaxmi Arcade, 9Th Main, 3Rd Block Pin Code - 560011 Blore - Hypercity Meenakshi Mall Inside Hypercity, Royal Meenakshi Mall, Bannerghatta Main Road, Pin Code - 560076 Brooke Field- Hypercity Ground Floor, Hypercity, Embassy Paragon, Kundalahalli Gate, ITPL Road, Whitefield Pin Code - 560037 Mumbai Andheri E- Tandon Mall Shop No. 4, Ground Floor, Tandon Mall, 127, Andheri Kurla Road, Andheri (E), Pin Code - 400049 Andheri W- Four Bungalows Shop No. 1 & 2, Building No. 24, Ashish CHS Ltd, St. Louis Road, Andheri (W), Pin Code - 400053 Andheri W- Lokhandwala 4,5,6 & 7, Silver Springs, Opp. HDFC Bank, Lokhandwala, Andheri (W) Pin Code - 400053 Andheri W- Shoppers Stop Level 4B, Shopper Stop, S.V. Road, Andheri (W) Pin Code - 400058 Bandra - Turner Road Hotel Grand Residency, Junction Of 24Th & 29Th Road, Off Turner Road, Near Tavaa Restaurant, Bandra (W), Pin Code - 400050 Bandra W- Opp Elco Market Soney Apartment, 45, Hill Road, Opp. -

The Great Indian Retail Saga All the Biggies in the International Retail Chain Are Waiting in the Wings to Snatch a Piece of the Retail Pie Writes Shanker

Retail The great Indian retail saga All the biggies in the international retail chain are waiting in the wings to snatch a piece of the retail pie writes Shanker ust like a lengthy soap opera, it retailer Wal-Mart to go one up. Will it her- much more. has been unfolding for almost a ald a flow of leading foreign retailer chains The entry of Wal-Mart had been in the year. Each episode brings a new to India? Well, one has to wait and watch. air for some time. So it comes as no sur- J development. The Indian public The share of organised retailing is about prise. The French retail giant Carrefour and has been lapping it up in right earnest. And 3 per cent of the total retail industry in the the UK-based Tesco are already in talks a quiet revolution is brewing in the Indian country estimated to be around $300 bil- with Indian companies to set foot in the retail space. lion. It is still dominated by the unorganised country. The Gulf-based Emke Group with Every industry major worth its salt is sector. But organised retail sector is pre- its popular Lulu hypermarkets has targeted putting money into retail ventures tempted dicted to grow at over 20 per cent annual- Kerala to open its account. by the thickening pay packets of the ly and touch $23 billion by 2010 indicating Of all the factors, none has energised spending public. Why not? For, statistics that there is room for more players. the organised retail sector than the entry of show that retail industry accounts for 10 It is this massive scope of the retail Reliance Industries Ltd., one of the leading per cent of the GDP of India, which is pro- industry that is prompting leading brands private sector players in the country. -

Food Delivery Platforms: Will They Eat the Restaurant Industry's Lunch?

Food Delivery Platforms: Will they eat the restaurant industry’s lunch? On-demand food delivery platforms have exploded in popularity across both the emerging and developed world. For those restaurant businesses which successfully cater to at-home consumers, delivery has the potential to be a highly valuable source of incremental revenues, albeit typically at a lower margin. Over the longer term, the concentration of customer demand through the dominant ordering platforms raises concerns over the bargaining power of these platforms, their singular control of customer data, and even their potential for vertical integration. Nonetheless, we believe that restaurant businesses have no choice but to embrace this high-growth channel whilst working towards the ideal long-term solution of in-house digital ordering capabilities. Contents Introduction: the rise of food delivery platforms ........................................................................... 2 Opportunities for Chained Restaurant Companies ........................................................................ 6 Threats to Restaurant Operators .................................................................................................... 8 A suggested playbook for QSR businesses ................................................................................... 10 The Arisaig Approach .................................................................................................................... 13 Disclaimer .................................................................................................................................... -

(Combination Registration No. C-2017/10/529) 16

Fair Competition For Greater Good COMPETITION COMMISSION OF INDIA (Combination Registration No. C-2017/10/529) 16th November, 2017 Notice under Section 6 (2) of the Competition Act, 2002 filed by Future Retail Limited. CORAM: Mr.Devender Kumar Sikri Chairperson Mr. S.L. Bunker Member Mr. Sudhir Mital Member Mr. Augustine Peter Member Mr. U.C. Nahta Member Legal Representative: AZB & Partners Order under Section 31(1) of the Competition Act, 2002 1. On 13th October, 2017, Future Retail Limited (‘FRL’/ ‘Acquirer’) filed a notice under sub-section (2) of Section 6 of the Competition Act, 2002 pursuant to the execution of Share Purchase Agreement (‘SPA’) entered into and between FRL, Hypercity Retail (India) Ltd. (‘HRIL’) and shareholders of HRIL (‘Sellers’) on 8th October, 2017 (‘Hereinafter FRL and HRIL are together referred to as ‘Parties’). Page 1 of 5 COMPETITION COMMISSION OF INDIA (Combination Registration No. C-2017/10/529) Fair Competition For Greater Good 2. The proposed combination relates to acquisition of 100 per cent share capital of HRIL by FRL in a cash and stock transaction. The notice for proposed combination has been filed under sub-section 2 of Section 6 read with sub-section (a) of Section 5 the Competition Act, 2002). (“Act” 3. FRL, a group company of Future Group, is a public limited company listed on Bombay Stock Exchange (‘BSE’) and National Stock Exchange (‘NSE’). It operates stores under multiple formats such as hypermarket, supermarket and home segments and under different brand names including Big Bazaar, FBB, Food Bazaar, Foodhall, Home Town, and eZone. The retail stores of FRL deal in following broad categories of products, viz., grocery (including fruits and vegetables, staples etc.), general merchandise, consumer durables and IT, apparel & footwear etc. -

Home Bistro, Inc. (Otc – Hbis)

Investment and Company Research Opportunity Research COMPANY REPORT January 28, 2021 HOME BISTRO, INC. (OTC – HBIS) Sector: Consumer Direct Segment: Gourmet, Ready-Made Meals www.goldmanresearch.com Copyright © Goldman Small Cap Research, 2021 Page 1 of 16 Investment and Company Research Opportunity Research COMPANY REPORT HOME BISTRO, INC. Pure Play Gourmet Meal Delivery Firm Making All the Right Moves Rob Goldman January 28, 2021 [email protected] HOME BISTRO, INC. (OTC – HBIS - $1.25) COMPANY SNAPSHOT INVESTMENT HIGHLIGHTS Home Bistro provides high quality, direct-to- Home Bistro is a pure play gourmet meal consumer, ready-made gourmet meals delivery firm enjoying outsized growth and could at www.homebistro.com, which includes meals emerge as one of the stars of the multi-billion- inspired and created by celebrity “Iron Chef” Cat dollar industry. HBIS’s approach and model Cora. The Company also offers restaurant quality represent a major differentiator and should drive meats and seafood through its Prime enviable sales and profit, going forward. Chop www.primechop.co and Colorado Prime brands. The HBIS positioning as the go-to, high-end, high quality provider is further enhanced via its KEY STATISTICS exclusive relationship with celebrity Iron Chef Cat Cora. HBIS now offers meals inspired and created by Cat alongside its world class chef- Price as of 1/27/21 $1.25 prepared company entrees. $6.0147 - 52 Week High – Low $0.192 M&A of HBIS competitors illustrates the Est. Shares Outstanding 11.4M underlying value for the Company and its Market Capitalization $24,3M segment. Nestle bought a competitor for up to $1.5 Average Volume 1,136 billion to get a footprint in the space. -

ONLINE GROCERY RETAIL in MENA Table of Contents

2019 ONLINE GROCERY RETAIL IN MENA Table of contents Introduction ................................................................ 3 Definitions ............................................................................. 5 Pure Play ................................................................................ 7 Marketplace ........................................................................... 8 Omni-Channel ....................................................................... 9 Sector Overview .......................................................... 10 Global Market ............................................................. 14 MENA Market Overview ................................................ 18 Benchmarking Players in MENA ..................................... 35 Conclusion .................................................................. 53 Introduction For many households across the Middle East and North Africa’s (MENA) rural areas, a significant part of the day is the call of the grocer, shouting out the day’s produce and price. The fresh fruit and vegetables laid out on a cart, usually pulled by a horse or donkey, is the most basic form of food delivery. In more urban areas, phoning up the local grocery store to deliver staple goods is commonplace and now, as technology permeates further into the e-commerce space, ordering groceries online will be the technological equivalent of the vegetable cart at your door. While 58 per cent of consumers in the region still prefer to do their weekly shop instore at large supermarkets, -

Ocado Group Plc Annual Report and Accounts for the 52 Weeks Ended 2 December 2018 ®

Ocado Group plc Group Ocado Annual Report and Accounts for the 52 weeks ended 2 December 2018 the 52 weeks ended 2 December for and Accounts Annual Report ® OCADO GROUP PLC ANNUAL REPORT AND ACCOUNTS WWW.OCADOGROUP.COM FOR THE 52 WEEKS ENDED 2 DECEMBER 2018 Ocado AR2018 Strategic Report.indd 3 05-Feb-19 2:07:23 AM 26237 5 February 2019 1:58 am Proof 6 Purpose: changing the way the world shops Mission: Powered by fresh thinking, we strive for new and improved ways to deliver the world’s most advanced end-to-end online shopping and delivery solutions. We are built for this – nobody does it better. Ocado AR2018 Strategic Report.indd 4 05-Feb-19 2:07:45 AM 26237 5 February 2019 1:58 am Proof 6 26237 5 February 2019 1:58 am Proof 6 Now is our time 01 WHAT’S INSIDE notes-heading-level-one notes-heading-level-two 1. NOW IS OUR TIME notes-heading-level-three 04 To give our customers the best notes-heading-level-four shopping experience 06 Our people create pioneering technology notes-strapline CHANGING THE WAY notes-text-body 08 That powers the most advanced solutions THE WORLD SHOPS 10 For the world’s leading retailers to invest in • notes-list-bullet We are transforming shopping, making it as • notes-list-bespoke 2. STRATEGIC REPORT easy and efficient as possible. We are online 14 Why Invest in Ocado? − notes-list-dash grocery pioneers. We have unique knowledge 15 Progress in 2018 d. notes-list-alpha and inspired people delivering the best possible 16 Q&A with Tim Steiner 5. -

Mumbai District

Government of India Ministry of MSME Brief Industrial Profile of Mumbai District MSME – Development Institute Ministry of MSME, Government of India, Kurla-Andheri Road, Saki Naka, MUMBAI – 400 072. Tel.: 022 – 28576090 / 3091/4305 Fax: 022 – 28578092 e-mail: [email protected] website: www.msmedimumbai.gov.in 1 Content Sl. Topic Page No. No. 1 General Characteristics of the District 3 1.1 Location & Geographical Area 3 1.2 Topography 4 1.3 Availability of Minerals. 5 1.4 Forest 5 1.5 Administrative set up 5 – 6 2 District at a glance: 6 – 7 2.1 Existing Status of Industrial Areas in the District Mumbai 8 3 Industrial scenario of Mumbai 9 3.1 Industry at a Glance 9 3.2 Year wise trend of units registered 9 3.3 Details of existing Micro & Small Enterprises and artisan 10 units in the district. 3.4 Large Scale Industries/Public Sector undertaking. 10 3.5 Major Exportable item 10 3.6 Growth trend 10 3.7 Vendorisation /Ancillarisation of the Industry 11 3.8 Medium Scale Enterprises 11 3.8.1 List of the units in Mumbai district 11 3.9 Service Enterprises 11 3.9.2 Potentials areas for service industry 11 3.10 Potential for new MSME 12 – 13 4 Existing Clusters of Micro & Small Enterprises 13 4.1 Details of Major Clusters 13 4.1.1 Manufacturing Sector 13 4.2 Details for Identified cluster 14 4.2.1 Name of the cluster : Leather Goods Cluster 14 5 General issues raised by industry association during the 14 course of meeting 6 Steps to set up MSMEs 15 Annexure - I 16 – 45 Annexure - II 45 - 48 2 Brief Industrial Profile of Mumbai District 1. -

On-Demand Grocery Disruption

QUARTERLY SHAREHOLDER LETTER Topic: On-demand Grocery Disruption 31 March 2021 Dear Shareholder, Until the great Covid boost of 2020, grocery shopping was slower to move online than many categories. Demand was muted for a few reasons: groceries have lowish ticket sizes – lower, at least, than consumer electronics or high fashion – and low margins; people tend to buy food from companies they trust (particularly fresh food); shopping behaviour is sticky due to the relatively habitual, high frequency nature of grocery shopping, and barriers such as delivery fees were off-putting. On the other hand, the supply side struggled with complicated supply chains and difficult-to-crack economics. However, the lengthy Covid pandemic has encouraged people to experiment at a time when the level of digital adoption has made it a whole lot easier for suppliers to reach scale. Unsurprisingly, recent surveys indicate that most people who tried online grocery shopping during the pandemic will continue to do it post Covid. We therefore expect continued growth in online grocery penetration, and within online grocery, on-demand services that deliver in a hurry are likely to keep growing faster, from less than 10% of the total online grocery bill in most markets today. Ready when you are This letter focuses on the threats and opportunities facing companies from the growth in on-demand grocery shopping. We look at on-demand specifically as we think it will be the most relevant channel for online groceries in EM, and could be the most disruptive. The Fund is exposed to the trend in several ways.