File Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Supranuclear and Internuclear Ocular Motility Disorders

CHAPTER 19 Supranuclear and Internuclear Ocular Motility Disorders David S. Zee and David Newman-Toker OCULAR MOTOR SYNDROMES CAUSED BY LESIONS IN OCULAR MOTOR SYNDROMES CAUSED BY LESIONS OF THE MEDULLA THE SUPERIOR COLLICULUS Wallenberg’s Syndrome (Lateral Medullary Infarction) OCULAR MOTOR SYNDROMES CAUSED BY LESIONS OF Syndrome of the Anterior Inferior Cerebellar Artery THE THALAMUS Skew Deviation and the Ocular Tilt Reaction OCULAR MOTOR ABNORMALITIES AND DISEASES OF THE OCULAR MOTOR SYNDROMES CAUSED BY LESIONS IN BASAL GANGLIA THE CEREBELLUM Parkinson’s Disease Location of Lesions and Their Manifestations Huntington’s Disease Etiologies Other Diseases of Basal Ganglia OCULAR MOTOR SYNDROMES CAUSED BY LESIONS IN OCULAR MOTOR SYNDROMES CAUSED BY LESIONS IN THE PONS THE CEREBRAL HEMISPHERES Lesions of the Internuclear System: Internuclear Acute Lesions Ophthalmoplegia Persistent Deficits Caused by Large Unilateral Lesions Lesions of the Abducens Nucleus Focal Lesions Lesions of the Paramedian Pontine Reticular Formation Ocular Motor Apraxia Combined Unilateral Conjugate Gaze Palsy and Internuclear Abnormal Eye Movements and Dementia Ophthalmoplegia (One-and-a-Half Syndrome) Ocular Motor Manifestations of Seizures Slow Saccades from Pontine Lesions Eye Movements in Stupor and Coma Saccadic Oscillations from Pontine Lesions OCULAR MOTOR DYSFUNCTION AND MULTIPLE OCULAR MOTOR SYNDROMES CAUSED BY LESIONS IN SCLEROSIS THE MESENCEPHALON OCULAR MOTOR MANIFESTATIONS OF SOME METABOLIC Sites and Manifestations of Lesions DISORDERS Neurologic Disorders that Primarily Affect the Mesencephalon EFFECTS OF DRUGS ON EYE MOVEMENTS In this chapter, we survey clinicopathologic correlations proach, although we also discuss certain metabolic, infec- for supranuclear ocular motor disorders. The presentation tious, degenerative, and inflammatory diseases in which su- follows the schema of the 1999 text by Leigh and Zee (1), pranuclear and internuclear disorders of eye movements are and the material in this chapter is intended to complement prominent. -

Neurologic Outcomes in Friedreich Ataxia: Study of a Single-Site Cohort E415

Volume 6, Number 3, June 2020 Neurology.org/NG A peer-reviewed clinical and translational neurology open access journal ARTICLE Neurologic outcomes in Friedreich ataxia: Study of a single-site cohort e415 ARTICLE Prevalence of RFC1-mediated spinocerebellar ataxia in a North American ataxia cohort e440 ARTICLE Mutations in the m-AAA proteases AFG3L2 and SPG7 are causing isolated dominant optic atrophy e428 ARTICLE Cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy revisited: Genotype-phenotype correlations of all published cases e434 Academy Officers Neurology® is a registered trademark of the American Academy of Neurology (registration valid in the United States). James C. Stevens, MD, FAAN, President Neurology® Genetics (eISSN 2376-7839) is an open access journal published Orly Avitzur, MD, MBA, FAAN, President Elect online for the American Academy of Neurology, 201 Chicago Avenue, Ann H. Tilton, MD, FAAN, Vice President Minneapolis, MN 55415, by Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. at 14700 Citicorp Drive, Bldg. 3, Hagerstown, MD 21742. Business offices are located at Two Carlayne E. Jackson, MD, FAAN, Secretary Commerce Square, 2001 Market Street, Philadelphia, PA 19103. Production offices are located at 351 West Camden Street, Baltimore, MD 21201-2436. Janis M. Miyasaki, MD, MEd, FRCPC, FAAN, Treasurer © 2020 American Academy of Neurology. Ralph L. Sacco, MD, MS, FAAN, Past President Neurology® Genetics is an official journal of the American Academy of Neurology. Journal website: Neurology.org/ng, AAN website: AAN.com CEO, American Academy of Neurology Copyright and Permission Information: Please go to the journal website (www.neurology.org/ng) and click the Permissions tab for the relevant Mary E. -

THE SYNDROMES of the ARTERIES of the BRAIN and SPINAL CORD Part 1 by LESLIE G

65 Postgrad Med J: first published as 10.1136/pgmj.29.328.65 on 1 February 1953. Downloaded from THE SYNDROMES OF THE ARTERIES OF THE BRAIN AND SPINAL CORD Part 1 By LESLIE G. KILOH, M.D., M.R.C.P., D.P.M. First Assistant in the Joint Department of Psychological Medicine, Royal Victoria Infirmary and University of Durham Introduction general circulatory efficiency at the time of the Little interest is shown at present in the syn- catastrophe is of the greatest importance. An dromes of the arteries of the brain and spinal cord, occlusion, producing little effect in the presence of and this perhaps is related to the tendency to a normal blood pressure, may cause widespread minimize the importance of cerebral localization. pathological changes if hypotension co-exists. Yet these syndromes are far from being fully A marked discrepancy has been noted between elucidated and understood. It must be admitted the effects of ligation and of spontaneous throm- that in many cases precise localization is often of bosis of an artery. The former seldom produces little more than academic interest and ill effects whilst the latter frequently determines provides Protected by copyright. nothing but a measure of personal satisfaction to infarction. This is probably due to the tendency the physician. But it is worth recalling that the of a spontaneous thrombus to extend along the detailed study of the distribution of the bronchi affected vessel, sealing its branches and blocking and of the pathological anatomy of congenital its collateral circulation, and to the fact that the abnormalities of the heart, was similarly neglected arterial disease is so often generalized. -

High-Yield Neuroanatomy

LWBK110-3895G-FM[i-xviii].qxd 8/14/08 5:57 AM Page i Aptara Inc. High-Yield TM Neuroanatomy FOURTH EDITION LWBK110-3895G-FM[i-xviii].qxd 8/14/08 5:57 AM Page ii Aptara Inc. LWBK110-3895G-FM[i-xviii].qxd 8/14/08 5:57 AM Page iii Aptara Inc. High-Yield TM Neuroanatomy FOURTH EDITION James D. Fix, PhD Professor Emeritus of Anatomy Marshall University School of Medicine Huntington, West Virginia With Contributions by Jennifer K. Brueckner, PhD Associate Professor Assistant Dean for Student Affairs Department of Anatomy and Neurobiology University of Kentucky College of Medicine Lexington, Kentucky LWBK110-3895G-FM[i-xviii].qxd 8/14/08 5:57 AM Page iv Aptara Inc. Acquisitions Editor: Crystal Taylor Managing Editor: Kelley Squazzo Marketing Manager: Emilie Moyer Designer: Terry Mallon Compositor: Aptara Fourth Edition Copyright © 2009, 2005, 2000, 1995 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, a Wolters Kluwer business. 351 West Camden Street 530 Walnut Street Baltimore, MD 21201 Philadelphia, PA 19106 Printed in the United States of America. All rights reserved. This book is protected by copyright. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, including as photocopies or scanned-in or other electronic copies, or utilized by any information storage and retrieval system without written permission from the copyright owner, except for brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. Materials appearing in this book prepared by individuals as part of their official duties as U.S. government employees are not covered by the above-mentioned copyright. To request permission, please contact Lippincott Williams & Wilkins at 530 Walnut Street, Philadelphia, PA 19106, via email at [email protected], or via website at http://www.lww.com (products and services). -

The Nomenclature of Human White Matter Association Pathways: Proposal for a Systematic Taxonomic Anatomical Classification

The Nomenclature of Human White Matter Association Pathways: Proposal for a Systematic Taxonomic Anatomical Classification Emmanuel Mandonnet, Silvio Sarubbo, Laurent Petit To cite this version: Emmanuel Mandonnet, Silvio Sarubbo, Laurent Petit. The Nomenclature of Human White Matter Association Pathways: Proposal for a Systematic Taxonomic Anatomical Classification. Frontiers in Neuroanatomy, Frontiers, 2018, 12, pp.94. 10.3389/fnana.2018.00094. hal-01929504 HAL Id: hal-01929504 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01929504 Submitted on 21 Nov 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. REVIEW published: 06 November 2018 doi: 10.3389/fnana.2018.00094 The Nomenclature of Human White Matter Association Pathways: Proposal for a Systematic Taxonomic Anatomical Classification Emmanuel Mandonnet 1* †, Silvio Sarubbo 2† and Laurent Petit 3* 1Department of Neurosurgery, Lariboisière Hospital, Paris, France, 2Division of Neurosurgery, Structural and Functional Connectivity Lab, Azienda Provinciale per i Servizi Sanitari (APSS), Trento, Italy, 3Groupe d’Imagerie Neurofonctionnelle, Institut des Maladies Neurodégénératives—UMR 5293, CNRS, CEA University of Bordeaux, Bordeaux, France The heterogeneity and complexity of white matter (WM) pathways of the human brain were discretely described by pioneers such as Willis, Stenon, Malpighi, Vieussens and Vicq d’Azyr up to the beginning of the 19th century. -

Monkey, and Cat Demonstrated by Acetylthiocholinesterase Staining

Proc. Nati. Acad. Sci. USA Vol. 75, No. 11, pp. 5723-5726, November 1978 Neurobiology Histochemically distinct compartments in the striatum of human, monkey, and cat demonstrated by acetylthiocholinesterase staining (basal ganglia/caudate nucleus/cholinergic transmission/acetylcholine/acetylcholinesterase, EC 3.1.1.7) ANN M. GRAYBIEL AND CLIFTON W. RAGSDALE, JR. Department of Psychology and Brain Science, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02139 Communicated by Walle J. H. Nauta, August 3,1978 ABSTRACT We here report observations on the distribution MATERIALS AND METHODS of acetylcholinesterase (acetylcholine hydrolase, EC 3.1.1.7) in the striatum of the adult human, the rhesus monkey, and the cat. This report is based on a study of postmortem striatal tissue from By the histochemical staining methods of Geneser-Jensen and the brains of three humans, two monkeys, seven cats, and three Blackstad and of Karnovsky and Roots, compartments of low kittens. cholinesterase activity were identified in parts of the striatum Human autopsy material was obtained 11-26 hr after death in all three species. In frontal sections, these enzyme-poor zones from two men (HI and H2, ages 72 and 74 years) and one appeared as a variable number of weakly stained t0.5-mm-wide woman (H3, age 76 years). Tissue blocks containing part of the zones embedded in a darkly stained background. The zones head of the caudate nucleus or lentiform nucleus and control varied in cross-sectional shape from round to elongated and blocks from the brainstem were immersed for 4-20 hr in a so- were sometimes branched. They were most prominent in the lution of fixative head of the caudate nucleus. -

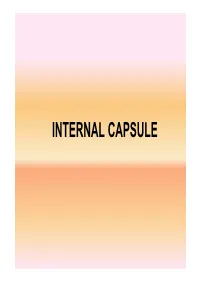

INTERNAL CAPSULE • Projection Fibres- Internal Capsule

INTERNAL CAPSULE • Projection fibres- Internal capsule r ~OnQih..!1c:lll i~J ~asd · I.JS OOi 1n1ssur DEFINITION Rostrum ol co,pi.c:; • Projection fibres c.allosum (white matter) between nucleus • caudate nucleus and /---~.__~---- :r~~l thalamus medially capS,Jle Pos1enu1 1111-0 of 1mema1 • lentiform nucleus capsule Thalamus laterally Actf'CNeflocular part of internal capsule 10.24 Horizontal sec11u11 01 lilt cerebral hemisphere st10win9 the Ooc1pr1~• p<Jlt!' - nl lhti rnla o-n~I r~n-e-11l it • Internal Capsule- A compact bundle of fibres through which the large collections of fibres pass, including- • Thalamocortical fibres • Corticothalamic fibres • Corticopontine fibres • Corticobulbar fibres • Corticospinal fibres • The fibres project from the cerebral cortex to the various nuclei of the extrapyramidal system (e.g., the putamen and caudate nucleus). • It is a continuous sheet of fibres that forms the medial boundary of the lenticular nucleus. • It continues around posteriorly and inferiorly to partially envelop this nucleus. • Inferiorly, many of the fibres of the internal capsule funnel into the cerebral peduncles. • Superiorly, the fibres fan out into the corona radiata. • Here, they travel in the cerebral white matter to reach their cortical origins or destinations. The internal capsule is divided into 5 regions: • The anterior limb is the portion between the lenticular nucleus and the head of the caudate nucleus; • The posterior limb is the portion between the lenticular nucleus and the thalamus; • The genu is the portion at the junction of the above 2 parts and is adjacent to the interventricular foramen; • The retrolenticular part is the portion posterior to the lenticular nucleus; • The sublenticular part is the portion inferior to the lenticular nucleus. -

White Matter Anatomy: What the Radiologist Needs to Know

White Matter Anatomy What the Radiologist Needs to Know Victor Wycoco, MBBS, FRANZCRa, Manohar Shroff, MD, DABR, FRCPCa,*, Sniya Sudhakar, MBBS, DNB, MDb, Wayne Lee, MSca KEYWORDS Diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) White matter tracts Projection fibers Association Fibers Commissural fibers KEY POINTS Diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) has emerged as an excellent tool for in vivo demonstration of white matter microstructure and has revolutionized our understanding of the same. Information on normal connectivity and relations of different white matter networks and their role in different disease conditions is still evolving. Evidence is mounting on causal relations of abnormal white matter microstructure and connectivity in a wide range of pediatric neurocognitive and white matter diseases. Hence there is a pressing need for every neuroradiologist to acquire a strong basic knowledge of white matter anatomy and to make an effort to apply this knowledge in routine reporting. INTRODUCTION (Fig. 1). However, the use of specific DTI sequences provides far more detailed and clini- DTI has allowed in vivo demonstration of axonal cally useful information. architecture and connectivity. This technique has set the stage for numerous studies on normal and abnormal connectivity and their role in devel- DIFFUSION TENSOR IMAGING: THE BASICS opmental and acquired disorders. Referencing established white matter anatomy, DTI atlases, Using appropriate magnetic field gradients, and neuroanatomical descriptions, this article diffusion-weighted sequences can be used to summarizes the major white matter anatomy and detect the motion of the water molecules to and related structures relevant to the clinical neurora- from cells. This free movement of the water mole- diologist in daily practice. -

Progressive Supranuclear Palsy Update

5 Progressive Supranuclear Palsy Dr D Paviour1 and Professor D Burn2 1. Consultant Neurologist, St George’s University Hospital 2. Professor of Movement Disorder Neurology and Honorary Consultant Neurologist, Institute for Ageing and Health, Newcastle University Introduction Tauopathies constitute a group of neurodegenerative conditions characterised by the deposition of tau protein-containing neurofibrillary tangles. Cognitive impairment and extrapyramidal features are features common to the majority of tauopathies. Mutations in the tau gene (MAPT) or alterations in the expression of tau protein isoforms have been implicated in the molecular pathophysiology of these disorders. This, in turn, has led to a nosology of tauopathies, defined according to the nature of the predominant tau isoform, and explained in more detail below. Progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP, or Steele-Richardson-Olszewski syndrome), corticobasal degeneration and argyrophilic grain disease are thus classified as “four-repeat” tauopathies. In its full-blown form, the clinical picture of PSP is highly characteristic. The patient has a fixed “Mona Lisa” stare, with a markedly reduced blink frequency. The head is retracted and the voice is reduced to a distinctive slurred growl. The patient walks clumsily and unsteadily (like a “drunken sailor”), with a notable tendency to topple backwards. Motor recklessness is often an early feature, leading to the highly distinctive “rocket sign” on rising from a chair. Clothes are soiled with spilled food, due an inability to look down at the plate and difficulties swallowing (the “messy-tie” sign). The time taken to respond to a question is prolonged, because of slow cognitive processing (bradyphrenia). There is sometimes palilalia or echolalia. -

Review Article Anatomy of the Temporal Lobe

Hindawi Publishing Corporation Epilepsy Research and Treatment Volume 2012, Article ID 176157, 12 pages doi:10.1155/2012/176157 Review Article AnatomyoftheTemporalLobe J. A. Kiernan Department of Anatomy and Cell Biology, The University of Western Ontario, London, ON, Canada N6A 5C1 Correspondence should be addressed to J. A. Kiernan, [email protected] Received 6 October 2011; Accepted 3 December 2011 Academic Editor: Seyed M. Mirsattari Copyright © 2012 J. A. Kiernan. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Only primates have temporal lobes, which are largest in man, accommodating 17% of the cerebral cortex and including areas with auditory, olfactory, vestibular, visual and linguistic functions. The hippocampal formation, on the medial side of the lobe, includes the parahippocampal gyrus, subiculum, hippocampus, dentate gyrus, and associated white matter, notably the fimbria, whose fibres continue into the fornix. The hippocampus is an inrolled gyrus that bulges into the temporal horn of the lateral ventricle. Association fibres connect all parts of the cerebral cortex with the parahippocampal gyrus and subiculum, which in turn project to the dentate gyrus. The largest efferent projection of the subiculum and hippocampus is through the fornix to the hypothalamus. The choroid fissure, alongside the fimbria, separates the temporal lobe from the optic tract, hypothalamus and midbrain. The amygdala comprises several nuclei on the medial aspect of the temporal lobe, mostly anterior the hippocampus and indenting the tip of the temporal horn. The amygdala receives input from the olfactory bulb and from association cortex for other modalities of sensation. -

Neurobiology of Addiction

The Neurological Basis of Addiction Implications for Treating Substance Abuse Ramnarine Boodoo Learning Objectives • By the end of this activity, participants will be able to - – Describe the normal structure and function of the brain as it relates to addiction – Describe salient brain changes that occur as a result of addiction – Understand the implications of such changes in the treatment of substance abuse Presentation Outline • Neurobiology of Addiction – Neuroanatomy – Circuitry of Reward • Substance Use Disorders – Definition of Addiction – How Neural Dysfunction Maintains Addiction – Stages of Addiction – Implications for Treatment Neuroanatomy • The Human Nervous System – CNS - The Brain and Spinal Cord – PNS – Peripheral Motor and Sensory Nerves – ANS – Autonomic Nerves, Sympathetic vs Parasympathetic Neuroanatomy • CNS Anatomy - – Anatomy of the Brain • The brain is a complicated structure • Has important structures on the surface and embedded within it – It is really helpful (but possibly difficult) to think in 3-D • Has many interacting parts, both grossly and microscopically • No one is absolutely sure about how these parts interact • The brain is plastic, i.e. structure and function can change with various forms of stimulation, both biological and psychological • All of the above factors have a part to play in understanding addiction From: Neuroanatomy of Dopamine: Reward and Addiction The Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences COVER and FIGURE 1. Approximate portions of the prefrontal cortex (PFC), important for reward, are color- coded (dorsal anterior cingulate cortex [ACC]: pink; ventral PFC: orange; orbital PFC: blue) on the left side of axial (A–C) and coronal (D–G) MRIs. Approximate extent and locations of major midbrain dopamine nuclei important for reward (dark green) and the major dopaminergic tracts (mesocortical: purple; mesostriatal: red; mesolimbic: dark blue) are color-coded on the right side of axial (A–C) and coronal (D–G) MRIs. -

Differential Activation of Dorsal Basal Ganglia During Externally and Self

Brain Imaging 1111 Website publication 21 April 1998 NeuroReport 9, 1567–1573 (1998) 2 3 THEbasal ganglia are thought to be critically involved 4 in motor control. However, the relative contributions of Differential activation 5 the various sub-components are not known. Although, 6 in principle, functional magnetic resonance imaging of dorsal basal ganglia 7 (fMRI) provides adequate resolution to image the basal during externally and 8 ganglia at the spatial scale of the individual nuclei, acti- vating these nuclei with fMRI has proven to be difficult. 9 Here we report two tasks, involving externally and self self paced sequences 10111 paced sequences of arm movements, which resulted in 1 significant activation of contralateral posterior (post- of arm movements 2 commissural) putamen and globus pallidus. This activa- 3 tion did not significantly differ between the tasks. In V. Menon,1,3,CA G. H. Glover2 contrast, significant activation of the contralateral and 1,4 4 ipsilateral anterior caudate and anterior putamen was and A. Pfefferbaum 5 observed only during externally paced arm movements. 6 These results suggest a dissociation in the roles of the Departments of 1Psychiatry and Behavioral 7 anterior and posterior dorsal basal ganglia: the anterior Sciences and 2Radiology, Stanford University 8 caudate and putamen may be involved in sensory to School of Medicine, Stanford, CA 94305-5550; motor mapping and the posterior putamen and globus 9 3Palo Alto VA Health Care System; and pallidus may be involved in the motor response itself. 4 20111 The findings support the hypothesis that the basal SRI International, USA 1 ganglia may be involved in gating sensory influences 2 onto motor areas .