The Evolution of Belarusian Public Sector: from Command Economy to State Capitalism?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

European and National Dimension in Research

MINISTRY OF EDUCATION OF BELARUS Polotsk State University EUROPEAN AND NATIONAL DIMENSION IN RESEARCH ЕВРОПЕЙСКИЙ И НАЦИОНАЛЬНЫЙ КОНТЕКСТЫ В НАУЧНЫХ ИССЛЕДОВАНИЯХ MATERIALS OF VI JUNIOR RESEARCHERS’ CONFERENCE (Novopolotsk, April 22 – 23, 2014) In 3 Parts Part 1 HUMANITIES Novopolotsk PSU 2014 UDC 082 Publishing Board: Prof. Dzmitry Lazouski ( chairperson ); Dr. Dzmitry Hlukhau (vice-chairperson ); Mr. Siarhei Piashkun ( vice-chairperson ); Dr. Maryia Putrava; Ms. Liudmila Slavinskaya Редакционная коллегия : д-р техн . наук , проф . Д. Н. Лазовский ( председатель ); канд . техн . наук , доц . Д. О. Глухов ( зам . председателя ); С. В. Пешкун ( зам . председателя ); канд . филол . наук , доц . М. Д. Путрова ; Л. Н. Славинская The first two conferences were issued under the heading “Materials of junior researchers’ conference”, the third – “National and European dimension in research”. Junior researchers’ works in the fields of humanities, social sciences, law, sport and tourism are presented in the second part. It is intended for trainers, researchers and professionals. It can be useful for university graduate and post- graduate students. Первые два издания вышли под заглавием « Материалы конференции молодых ученых », третье – «Национальный и европейский контексты в научных исследованиях ». В первой части представлены работы молодых ученых по гуманитарным , социальным и юридиче- ским наукам , спорту и туризму . Предназначены для работников образования , науки и производства . Будут полезны студентам , маги- странтам и аспирантам университетов . ISBN 978-985-531-444-9 (P. 1) © Polotsk State University, 2014 ISBN 978-985-531-443-2 MATERIALS OF V JUNIOR RESEARCHERS’ CONFERENCE 2014 Linguistics, Literature, Philology LINGUISTICS, LITERATURE, PHILOLOGY UDC 821.111.09=111 THE DECONSTRUCTION OF GENDER ROLES IN "THE GRAPES OF WRATH" BY JOHN STEINBECK ON THE EXAMPLE OF MA JOAD LIZAVETA BALSHAKOVA, DZYANIS KANDAKOU Polotsk State University, Belarus The Grapes of Wrath, has been read and reread by millions, pondered and set down in a thousand essays and books. -

Investment and Trade Policy of the Republic of Belarus

INVESTMENT AND TRADE POLICY OF THE REPUBLIC OF BELARUS Igor Ugorich Head of Department, Foreign Trade Administration, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Belarus Globalisation creates a situation where the conflicts in certain regions directly affect the global state of affairs. From this perspective, developments in the 21st Century will be largely influenced by processes taking shape in the whole world. Multi-ethnic and multi-confessional Belarus has avoided the religious and ethnic conflicts so characteristic of many post-Soviet countries. Organised government management and law-enforcement systems have allowed us to ensure an adequate level of security for our society and people. The strategy of economic development, priorities and the stages of reformation of the economy of Belarus are based on the so-called “Belarusan model” of development, which is a socially orientated market economy stipulated by the Constitution and with regard to the place and the role of our state in the world community. Reformation of the Belarusan economy started in 1991 after the dissolution of the USSR. The current stage of reformation and development started in 1994-1995 and is connected with cardinal changes in the economic policy of the state carried out before. Belarus looked for its own way of development in the years of crisis, one based on a sound pragmatic and practical understanding of world experience, taking into account particular internal problems and the general situation in the world. How should one build a programme of economic development? To ensure financial stabilisation at the cost of a drastic tightening of monetary and credit policy which would limit purchasing power (i.e. -

Stadler Inaugurated Its New Factory in Belarus

MEDIA RELEASE Fanipol, 20 November 2014 Stadler inaugurated its new factory in Belarus Alexander Lukashenko, President of the Republic of Belarus and Peter Spuhler, owner and CEO of Stadler Rail Group have today ceremonially inaugurated the new rolling stock manufacturing factory of Stadler established in Fanipol, Belarus. The new plant is responsible for the production of broad gauge rolling stock for CIS countries, including the starting project for the manufacturing of 21 double decker EMUs for Russian airport railways operator Aeroexpress. The maximum output of the factory at full capacity reaches the 120 carbodies per annum. The value of investment is EUR 76 million, while the number of employees is 600 people. Stadler decided to found a subsidiary and establish a factory in Belarus in order to supply dynamically developing CIS countries with the broad gauge products of the group. The reason behind establishing the factory in Fanipol was the available qualified workforce, its proximity to broad gauge countries, and the country’s customs union with Russia and Kazakhstan. The subsidiary was established in 2012 under the name of OJSC Stadler Minsk as a joint venture, originally with the majority ownership of Stadler Rail AG and the minority ownership Minsk Oblast Executive Committee. Later Stadler bought up the minority shares and became 100% owner of the Belarusian subsidiary. The value of investment Stadler has up till now performed in Belarus is totalling to EUR 76 million. The subsidiary currently employs altogether 600 people. Within the group OJSC Stadler Minsk is responsible for the production of broad gauge rolling stock ordered by customers operating in CIS countries. -

International Political Economy: Perspectives, Structures & Global

اﻟﻣﺟﻠﺔ اﻟﻌراﻗﯾﺔ ﻟﻠﻌﻠوم اﻻﻗﺗﺻﺎدﯾﺔ /Iraqi Journal for Economic Sciences اﻟﺳﻧﺔ اﻟﺗﺎﺳﻌﺔ –اﻟﻌدد اﻟﺛﺎﻣن واﻟﻌﺷرون/٢٠١١ International Political Economy: Perspectives, Structures & Global Problems Dr. Hanaa A. HAMMOOD Abstract This essay focuses on contemporary International Political Economy IPE science. IPE today widely appreciated and the subject of much theoretical research and applied policy analysis. The political actions of nation-states clearly affect international trade and monetary flows, which in turn affect the environment in which nation-states make political choices and entrepreneurs, make economic choices. It seems impossible to consider important questions of International Politics or International Economics without taking these mutual influences and effects into account .Both economic (market) and political (state) forces shape outcomes in international economic affairs. The interplay of these and their importance has increased as “globalization” has proceeded in recent years. Today’s Iraq faces many political, economic and social complex challenges, thus its openness and its integration into the global economy are necessary to overcome political and economic transition’s obstacles. This required an analysis within the frame of IPE to help economists, policy makers and civil society understand how economic and political conditions around the world impact present and future development in Iraq. The nature of dynamic interaction between state ( power-politic) and market ( wealth- economy) in changing globalized world will led in Iraq post – conflict country that their parallel existence often create tensions and greater economic and social role for the state. Iraq’s today face three main challenges; political challenge, financial resources challenge, and finally economic reforms challenges. Mixed economy for Iraq is perfect to move into a liberal economic system open to the global market conflict. -

Economic Liberalization and Its Impact on Human Development: a Comparative Analysis of Turkey and Azerbaijan Mayis G

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF ENVIRONMENTAL & SCIENCE EDUCATION 2016, VOL. 11, NO. 17, 9753-9771 OPEN ACCESS Economic liberalization and its impact on human development: A Comparative analysis of Turkey and Azerbaijan Mayis G. Gulaliyeva, Nuri I. Okb, Fargana Q. Musayevaa, Rufat J. Efendiyeva, Jamila Q. Musayevac, and Samira R. Agayevaa aThe Institute of Economics of Azerbaijan National Academy of Sciences, Baku, AZERBAIJAN; bIbrahim Chechen University, Agri, TURKEY; cMingachevir State University, Mingachevir, AZERBAIJAN. ABSTRACT The aim of the article is to study the nature of liberalization as a specific economic process, which is formed and developed under the influence of the changing conditions of the globalization and integration processes in the society, as well as to identify the characteristic differences in the processes of liberalization of Turkey and Azerbaijan economies (using the method of comparative analysis of these countries' development indices). The objectives of this study: the characterization of the liberalization process as a specific economic process; a comparative analysis of the Turkey and Azerbaijan economic development conditions; the improvement of the theoretical justification of influence the process of economic liberalization on the development of society. The article presents the comparative analysis of the Turkey and Azerbaijan economic development conditions by using new research method as index of leftness (rightness) of economy. It was revealed that the Azerbaijan economy compared with the economy of Turkey is using more “right” methods of economy regulation. The Turkish economy is more prone to fluctuations in the studied parameters, at the same time, a main way of Turkish economy development is the direction towards increased liberalization, while the simultaneous growth of indicators of the human development. -

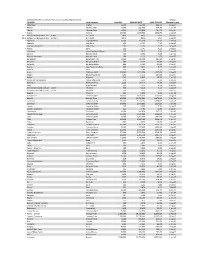

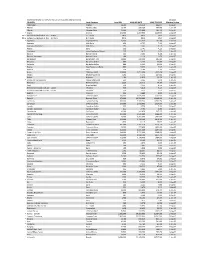

Maximum Monthly Stipend Rates For

MAXIMUM MONTHLY STIPEND RATES FOR FELLOWS AND SCHOLARS Jul 2020 COUNTRY Local Currency Local DSA MAX RES RATE MAX TRV RATE Effective % date * Afghanistan Afghani 12,600 132,300 198,450 1-Aug-07 * Albania Albania Lek(e) 14,000 220,500 330,750 1-Jan-05 Algeria Algerian Dinar 31,600 331,800 497,700 1-Aug-07 * Angola Kwanza 133,000 1,396,500 2,094,750 1-Aug-07 #N/A Antigua and Barbuda (1 Apr. - 30 Nov.) E.C. Dollar #N/A #N/A #N/A 1-Aug-07 #N/A Antigua and Barbuda (1 Dec. - 31 Mar.) E.C. Dollar #N/A #N/A #N/A 1-Aug-07 * Argentina Argentine Peso 18,600 153,450 230,175 1-Jan-05 Australia AUL Dollar 453 4,757 7,135 1-Aug-07 Australia - Academic AUL Dollar 453 1,200 7,135 1-Aug-07 * Austria Euro 261 2,741 4,111 1-Aug-07 * Azerbaijan (new)Azerbaijan Manat 239 1,613 2,420 1-Jan-05 Bahrain Bahraini Dinar 106 2,226 3,180 1-Jan-05 Bahrain - Academic Bahraini Dinar 106 1,113 1,670 1-Aug-07 Bangladesh Bangladesh Taka 12,400 130,200 195,300 1-Aug-07 Barbados Barbados Dollar 880 9,240 13,860 1-Aug-07 Barbados Barbados Dollar 880 9,240 13,860 1-Aug-07 * Belarus New Belarusian Ruble 600 5,850 8,775 1-Jan-06 Belgium Euro 338 3,549 5,324 1-Aug-07 Benin CFA Franc(XOF) 123,000 1,291,500 1,937,250 1-Aug-07 Bhutan Bhutan Ngultrum 7,290 76,545 114,818 1-Aug-07 * Bolivia Boliviano 1,200 10,800 16,200 1-Jan-07 * Bosnia and Herzegovina Convertible Mark 279 3,557 5,336 1-Jan-05 Botswana Botswana Pula 2,220 23,310 34,965 1-Aug-07 Brazil Brazilian Real 530 4,373 6,559 1-Jan-05 British Virgin Islands (16 Apr. -

Economy of Belarus Magazine

CONTENTS: FOUNDER: MODERNIZATION Council of Ministers of the Republic of Belarus MEMBERS: Alexei DAINEKO Ministry of Economy of the Republic of Belarus, Modernization: Ministry of Finance of the Republic of Belarus, Priorities and Essence Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Belarus, Belarusian Telegraph Agency BelTA A country’s prosperity hinges on the pace of its economic modernization 4 EDITORIAL BOARD: Tatyana IVANYUK Mikhail Prime Minister of Belarus, MYASNIKOVICH Corresponding Member of the National Academy Learning of Sciences of Belarus (NASB), Doctor of Economics, from Mistakes Professor (Chairman of the Editorial Board) Total investment spent on the upgrade of Belarus’ wood processing industry Boris BATURA Chairman of the Minsk Oblast is estimated at €801.9 million 9 Executive Committee Olga BELYAVSKAYA Igor VOITOV Chairman of the State Committee for Science and Technology, Doctor of Technical Sciences, A New Lease on Life Professor Belarus is set to upgrade about 3,000 enterprises in 2013 13 Igor VOLOTOVSKY Academic Secretary of the Department of Biological Sciences, NASB, Doctor of Biology, Professor Dmitry ZHUK Director General of Belarusian Telegraph Agency BelTA Vladimir ZINOVSKY Chairman of the National Statistics Committee Alexander Director General of the NASB Powder Metallurgy ILYUSHCHENKO Association, NASB Corresponding Member, Doctor of Technical Sciences, Professor Yekaterina NECHAYEVA Viktor KAMENKOV Chairman of the Supreme Economic Court, Ingredients of Success Doctor of Law, Professor Belarusian companies can rival many world-famous producers 16 Dmitry KATERINICH Industry Minister IN THE SPOTLIGHT Sergei KILIN NASB сhief academic secretary, NASB Corresponding Member, Doctor of Physics and Mathematics, Tatyana POLEZHAI Professor Business Plan Nikolai LUZGIN First Deputy Chairman of the Board of the National for the Country Bank of the Republic of Belarus, Ph.D. -

01036456.Pdf

C/64-10b News Broadcasting on Soviet Radio and Television F. Gayle Durham Research Program on Problems of Communication and International SecU-itv Center for International Studies Massachusetts Institute of Technology Cambridge, Massachusetts June, 1965 Preface The present paper is one result of several months' research on radio and television broadcasting in the Soviet Union. It is viewed by the author as a preliminary survey of the subject, which will be expanded and developed in the coming months. In addition to a general updating of material on policy and mechanical actualities, more atten- tion will be given to the proportion of different types of news which are broadcast, and to the personnel who handle news. Of extreme importance is the position which news broadcasting occupies in the process of informing the individual Soviet citizen. This aspect will be considered as part of a general study on information-gathering in Soviet society. The research for this paper was sponsored by the Advanced Research Projects Agency of the Department of Defense (ARPA) under contract #920F-9717 and monitored by the Air Force Office of Scientific Research (AFOSR) under contract AF 49(638)-1237. Table of Contents Page I. Introduction:The Soviet Conception of the Functional Role of Broadcasting Media and II. Radio News Broadcasting................................7 A. Mechanics of News Broadcasts.........................7 3. The Newsgathering Apparatus .................... .22 4. Party Influence.................,.. .26 B. Content of Broadcasts....................,*....*.. .. 29 l. Characteristics...................,..........,........29 2. Forms.... ....... .... * e .......... 32 3. Types of News. .................................. 3 III. Television News Broadcasting.......... .............. 0 .39 IV. Summary and Conclusion............................. V. Footnotes ...... .. ... ... .... ... ... .4 VI. Appendices One: Monitor Summaries of News Broadcasts (1963)........51 Two:Chart:Broadcasts on Moscow Radio with News Content. -

Market Socialism As a Distinct Socioeconomic Formation Internal to the Modern Mode of Production

New Proposals: Journal of Marxism and Interdisciplinary Inquiry Vol. 5, No. 2 (May 2012) Pp. 20-50 Market Socialism as a Distinct Socioeconomic Formation Internal to the Modern Mode of Production Alberto Gabriele UNCTAD Francesco Schettino University of Rome ABSTRACT: This paper argues that, during the present historical period, only one mode of production is sustainable, which we call the modern mode of production. Nevertheless, there can be (both in theory and in practice) enough differences among the specific forms of modern mode of production prevailing in different countries to justify the identification of distinct socioeconomic formations, one of them being market socialism. In its present stage of evolution, market socialism in China and Vietnam allows for a rapid development of productive forces, but it is seriously flawed from other points of view. We argue that the development of a radically reformed and improved form of market social- ism is far from being an inevitable historical necessity, but constitutes a theoretically plausible and auspicable possibility. KEYWORDS: Marx, Marxism, Mode of Production, Socioeconomic Formation, Socialism, Communism, China, Vietnam Introduction o our view, the correct interpretation of the the most advanced mode of production, capitalism, presently existing market socialism system (MS) was still prevailing only in a few countries. Yet, Marx Tin China and Vietnam requires a new and partly confidently predicted that, thanks to its intrinsic modified utilization of one of Marx’s fundamental superiority and to its inbuilt tendency towards inces- categories, that of mode of production. According to sant expansion, capitalism would eventually embrace Marx, different Modes of Production (MPs) and dif- the whole world. -

A Comparative Analysis of Media Freedom and Pluralism in the EU Member States

DIRECTORATE GENERAL FOR INTERNAL POLICIES POLICY DEPARTMENT C: CITIZENS' RIGHTS AND CONSTITUTIONAL AFFAIRS CIVIL LIBERTIES, JUSTICE AND HOME AFFAIRS A comparative analysis of media freedom and pluralism in the EU Member States STUDY Abstract This study was commissioned by the European Parliament's Policy Department for Citizens' Rights and Constitutional Affairs at the request of the LIBE Committee. The authors argue that democratic processes in several EU countries are suffering from systemic failure, with the result that the basic conditions of media pluralism are not present, and, at the same time, that the distortion in media pluralism is hampering the proper functioning of democracy. The study offers a new approach to strengthening media freedom and pluralism, bearing in mind the different political and social systems of the Member States. The authors propose concrete, enforceable and systematic actions to correct the deficiencies found. PE 571.376 EN ABOUT THE PUBLICATION This research paper was requested by the European Parliament's Committee on Civil Liberties, Justice and Home Affairs (LIBE) and commissioned, overseen and published by the Policy Department for Citizens' Rights and Constitutional Affairs. Policy Departments provide independent expertise, both in-house and external, to support EP committees and other parliamentary bodies in shaping legislation and exercising democratic scrutiny over EU external and internal policies. To contact the Policy Department for Citizens' Rights and Constitutional Affairs or to subscribe -

Countries Codes and Currencies 2020.Xlsx

World Bank Country Code Country Name WHO Region Currency Name Currency Code Income Group (2018) AFG Afghanistan EMR Low Afghanistan Afghani AFN ALB Albania EUR Upper‐middle Albanian Lek ALL DZA Algeria AFR Upper‐middle Algerian Dinar DZD AND Andorra EUR High Euro EUR AGO Angola AFR Lower‐middle Angolan Kwanza AON ATG Antigua and Barbuda AMR High Eastern Caribbean Dollar XCD ARG Argentina AMR Upper‐middle Argentine Peso ARS ARM Armenia EUR Upper‐middle Dram AMD AUS Australia WPR High Australian Dollar AUD AUT Austria EUR High Euro EUR AZE Azerbaijan EUR Upper‐middle Manat AZN BHS Bahamas AMR High Bahamian Dollar BSD BHR Bahrain EMR High Baharaini Dinar BHD BGD Bangladesh SEAR Lower‐middle Taka BDT BRB Barbados AMR High Barbados Dollar BBD BLR Belarus EUR Upper‐middle Belarusian Ruble BYN BEL Belgium EUR High Euro EUR BLZ Belize AMR Upper‐middle Belize Dollar BZD BEN Benin AFR Low CFA Franc XOF BTN Bhutan SEAR Lower‐middle Ngultrum BTN BOL Bolivia Plurinational States of AMR Lower‐middle Boliviano BOB BIH Bosnia and Herzegovina EUR Upper‐middle Convertible Mark BAM BWA Botswana AFR Upper‐middle Botswana Pula BWP BRA Brazil AMR Upper‐middle Brazilian Real BRL BRN Brunei Darussalam WPR High Brunei Dollar BND BGR Bulgaria EUR Upper‐middle Bulgarian Lev BGL BFA Burkina Faso AFR Low CFA Franc XOF BDI Burundi AFR Low Burundi Franc BIF CPV Cabo Verde Republic of AFR Lower‐middle Cape Verde Escudo CVE KHM Cambodia WPR Lower‐middle Riel KHR CMR Cameroon AFR Lower‐middle CFA Franc XAF CAN Canada AMR High Canadian Dollar CAD CAF Central African Republic -

Maximum Monthly Stipend Rates for Fellows And

MAXIMUM MONTHLY STIPEND RATES FOR FELLOWS AND SCHOLARS Sep 2020 COUNTRY Local Currency Local DSA MAX RES RATE MAX TRV RATE Effective % date Afghanistan Afghani 12,500 131,250 196,875 1-Aug-07 * Albania Albania Lek(e) 13,100 206,325 309,488 1-Jan-05 Algeria Algerian Dinar 31,600 331,800 497,700 1-Aug-07 * Angola Kwanza 134,000 1,407,000 2,110,500 1-Aug-07 #N/A Antigua and Barbuda (1 Apr. - 30 Nov.) E.C. Dollar #N/A #N/A #N/A 1-Aug-07 #N/A Antigua and Barbuda (1 Dec. - 31 Mar.) E.C. Dollar #N/A #N/A #N/A 1-Aug-07 * Argentina Argentine Peso 19,700 162,525 243,788 1-Jan-05 Australia AUL Dollar 453 4,757 7,135 1-Aug-07 Australia - Academic AUL Dollar 453 1,200 7,135 1-Aug-07 Austria Euro 261 2,741 4,111 1-Aug-07 Azerbaijan (new)Azerbaijan Manat 239 1,613 2,420 1-Jan-05 Bahrain Bahraini Dinar 106 2,226 3,180 1-Jan-05 Bahrain - Academic Bahraini Dinar 106 1,113 1,670 1-Aug-07 Bangladesh Bangladesh Taka 12,400 130,200 195,300 1-Aug-07 Barbados Barbados Dollar 880 9,240 13,860 1-Aug-07 Barbados Barbados Dollar 880 9,240 13,860 1-Aug-07 * Belarus New Belarusian Ruble 680 6,630 9,945 1-Jan-06 Belgium Euro 338 3,549 5,324 1-Aug-07 Benin CFA Franc(XOF) 123,000 1,291,500 1,937,250 1-Aug-07 Bhutan Bhutan Ngultrum 7,290 76,545 114,818 1-Aug-07 Bolivia Boliviano 1,180 10,620 15,930 1-Jan-07 * Bosnia and Herzegovina Convertible Mark 264 3,366 5,049 1-Jan-05 Botswana Botswana Pula 2,220 23,310 34,965 1-Aug-07 Brazil Brazilian Real 530 4,373 6,559 1-Jan-05 British Virgin Islands (16 Apr.