Sadu Weaving: the Pace of a Camel in a Fast-Moving Culture Lesli Robertson University of North Texas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Summer Cultural Festival August – September 2014 * Includes2bookreadingsessions Poetic Andheritage-Basedartsrefinethesecapabilities

The Annual Statistcial Book 2014 - 2015 Manal Alshurean Prepared by: Research, Studies and Planning Department Artist work In the Name of Allah, the Most Gracious, the Most Merciful His Highness the Emir of Kuwait Sheikh Sabah Al-Ahmad Al-Jaber Al-Sabah His Highness the Crown Prince Sheikh Nawaf Al-Ahmad Al-Jaber Al-Sabah His Highness the Prime Minister Sheikh Jaber Al-Mubarak Al-Hamad Al-Sabah His Highness Minister of Information, Minister of State for Youth Affairs And the President of National Council for Culture, Arts and Literature Sheikh Salman Sabah Salim Al-Hamud Al-Sabah Speech of His Excellency the Minister of Information for the Statistical Book In spite of its small area size and its humble number of population, Kuwait has established itself, since the dawn of modern renaissance, as a minaret of the Arabic Speech culture. With the deep faith in its Arab and Islamic belonging, both in identity and location, and upon its belief in the importance of the cultural work as a base to establish a large Arab community and as an engine to a comprehensive evolution in all aspects of life, Kuwait took upon itself the task of developing the Arab culture and exporting it to the Arab nation. Culture is indeed a cumulative work that benefits from the work of the past yet aiming towards the future to make a new tomorrow and a better life. Since its inception, and as the cultural arm of the State of Kuwait, the National Council for Culture, Arts and Letters has had a keen interest in the implementation of the State’s plan to enhance and promote the cultural development, not only locally but also in the entire Arab culture. -

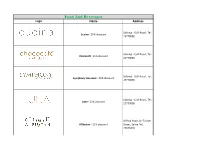

Food and Beverages Logo Name Address

Food And Beverages Logo Name Address Salmiya - Gulf Road , Tel: Cucina - 25% discount 25770000 Salmiya - Gulf Road , Tel: Chococafe- 25% discount 25770000 Salmiya - Gulf Road , Tel: Symphony Gourmet - 25% discount 25770000 Salmiya - Gulf Road , Tel: Luna - 25% discount 25770000 Al Bida Road, Al -Ta'awn Al Bustan - 25% discount Street, Salwa Tel: 25673410 Al Bida Road, Al -Ta'awn Eedam - 25% discount on homemade items only Street, Salwa Tel: 25673420 Al Bida Road, Al -Ta'awn Al Boom - 25% discount Street, Salwa Tel: 25673430 Al Bida Road, Al -Ta'awn Peacock - 25% discount during lunch only Street, Salwa Tel: 25673440 Marina mall / liwan/ the Nestle Toll House café - 15% discount village / Levels Tel : 22493773 Sharq, Al Hamra luxury Sushi bar - 12% discount center, 1st floor Sharq, Al Hamra luxury Versus Varsace Café - 12% discount center, 1st floor The Village, Kipco Tower Upper Crust - 10% discount Sharq Tel : 1821872 Murooj Sabhan Tel : Crumbs - 10% discount 22050270 Dar Al Awadhi, Kuwait Munch - 10% discount City Tel : 22322747 Gulf Road, Across from Mais Al Ghanim - 10% discount Kuwait Towers, Spoons Complex Tel: 22250655 Bneid Al gar - Al bastaki Mawal Lebnan Café & Restaurant - 15% discount hotel - 14th floor Tel : 22575169 Miral complex Tel : Debs Al reman - 15% Discount 22493773 Avenues Mall Tel : Boccini Pizzeria - 15% discount 22493773 Salmiya, Salem Mubarak ibis Hotel Restaurants- 20% discount Street and Sharq Tel : 25713872 Salmiya, Tel: 25742090- Dag Ayoush- 15% discount 55407179 Salmiya salem almubarak street - Basbakan- -

Al Koot Kuwait Provider Network

AlKoot Insurance & Reinsurance Partner Contact Details: Kuwait network providers list Partner name: Globemed Tel: +961 1 518 100 Email: [email protected] Agreement type Provider Name Provider Type Provider Address City Country Partner Al Salam International Hospital Hospital Bnaid Al Gar Kuwait City Kuwait Partner London Hospital Hospital Al Fintas Kuwait City Kuwait Partner Dar Al Shifa Hospital Hospital Hawally Kuwait City Kuwait Partner Al Hadi Hospital Hospital Jabriya Kuwait City Kuwait Partner Al Orf Hospital Hospital Al Jahra Kuwait City Kuwait Partner Royale Hayat Hospital Hospital Jabriyah Kuwait City Kuwait Partner Alia International Hospital Hospital Mahboula Kuwait City Kuwait Partner Sidra Hospital Hospital Al Reggai Kuwait City Kuwait Partner Al Rashid Hospital Hospital Salmiya Kuwait City Kuwait Partner Al Seef Hospital Hospital Salmiya Kuwait City Kuwait Partner New Mowasat Hospital Hospital Salmiya Kuwait City Kuwait Partner Taiba Hospital Hospital Sabah Al-Salem Kuwait City Kuwait Partner Kuwait Hospital Hospital Sabah Al-Salem Kuwait City Kuwait Partner Medical One Polyclinic Medical Center Al Da'iyah Kuwait City Kuwait Partner Noor Clinic Medical Center Al Ageila Kuwait City Kuwait Partner Quttainah Medical Center Medical Center Al Shaab Al Bahri Kuwait City Kuwait Partner Shaab Medical Center Medical Center Al Shaab Al Bahri Kuwait City Kuwait Partner Al Saleh Clinic Medical Center Abraq Kheetan Kuwait City Kuwait Partner Global Medical Center Medical Center Benaid Al qar Kuwait City Kuwait Partner New Life -

Travel Ban on Non-Vaccinated Violates Kuwaiti Constitution

Page 15 Page 16 THE FIRST ENGLISH LANGUAGE DAILY IN FREE KUWAIT ice hockey Established in 1977 / www.arabtimesonline.com basketball WEDNESDAY, MAY 5, 2021 / RAMADAN 23, 1442 AH emergency number 112 NO. 17681 16 PAGES 150 FILS MPs DECRY MINISTERIAL OVERREACH ... YOU DON’T OWN US Day by Day Travel ban on non-vaccinated THE whole country talks about dis- bursing bonuses to frontline workers who played a vital role in fighting the Covid-19 pandemic and the amount that has been allocated by the gov- ernment and those concerned with the issue makes no sense. So where violates Kuwaiti Constitution do we stand? In Britain, a country of seventy mil- lion people, no more than 60,000 peo- ple will receive the bonuses, while in Government backs two ministers Kuwait those who have registered for the rewards are about 214,000. We want an explanation from the government, since we hear a lot of By Saeed Mahmoud Saleh coronavirus, from travelling. noise but it falls on deaf ears. It is the Arab Times Staff and Agencies MP Osama Al-Shaheen said the decision is unconstitutional, asserting His Highness the time for a setback. Prime Minister Sheikh Sabah Al-Khaled and the concerned ministers should be held liable … Yet, tomorrow is just another KUWAIT CITY, May 4: Several MPs voiced objection to the decision day. politically and legally. He pointed out it is reasonable to encourage citizens to get vacci- Zahed Matar of the Cabinet to prevent citizens, who have not been vaccinated against nated, but forcing them to do so is unacceptable. -

Comparative Geomatic Analysis of Historic Development, Trends, And

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK Theses and Dissertations 5-2015 Comparative Geomatic Analysis of Historic Development, Trends, and Functions of Green Space in Kuwait City From 1982-2014 Yousif Abdullah University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd Part of the Near and Middle Eastern Studies Commons, Physical and Environmental Geography Commons, and the Urban Studies and Planning Commons Recommended Citation Abdullah, Yousif, "Comparative Geomatic Analysis of Historic Development, Trends, and Functions of Green Space in Kuwait City From 1982-2014" (2015). Theses and Dissertations. 1116. http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/1116 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Comparative Geomatic Analysis of Historic Development, Trends, and Functions Of Green Space in Kuwait City From 1982-2014. Comparative Geomatic Analysis of Historic Development, Trends, and Functions Of Green Space in Kuwait City From 1982-2014. A Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment Of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Art in Geography By Yousif Abdullah Kuwait University Bachelor of art in GIS/Geography, 2011 Kuwait University Master of art in Geography May 2015 University of Arkansas This thesis is approved for recommendation to the Graduate Council. ____________________________ Dr. Ralph K. Davis Chair ____________________________ ___________________________ Dr. Thomas R. Paradise Dr. Fiona M. Davidson Thesis Advisor Committee Member ____________________________ ___________________________ Dr. Mohamed Aly Dr. Carl Smith Committee Member Committee Member ABSTRACT This research assessed green space morphology in Kuwait City, explaining its evolution from 1982 to 2014, through the use of geo-informatics, including remote sensing, geographic information systems (GIS), and cartography. -

Globemed Kuwait Network of Providers Exc KSEC and BAYAN

GlobeMed Kuwait Network of HealthCare Providers As of June 2021 Phone ﺍﻻﺳﻡ ProviderProvider Name Name Region Region Phone Number FFaxax Number Number Hospitals 22573617 ﻣﺳﺗﺷﻔﻰ ﺍﻟﺳﻼﻡ ﺍﻟﺩﻭﻟﻲ Al Salam International Hospital Bnaid Al Gar 22232000 22541930 23905538 ﻣﺳﺗﺷﻔﻰ ﻟﻧﺩﻥ London Hospital Al Fintas 1 883 883 23900153 22639016 ﻣﺳﺗﺷﻔﻰ ﺩﺍﺭ ﺍﻟﺷﻔﺎء Dar Al Shifa Hospital Hawally 1802555 22626691 25314717 ﻣﺳﺗﺷﻔﻰ ﺍﻟﻬﺎﺩﻱ Al Hadi Hospital Jabriya 1828282 25324090 ﻣﺳﺗﺷﻔﻰ ﺍﻟﻌﺭﻑ Al Orf Hospital Al Jahra 2455 5050 2456 7794 ﻣﺳﺗﺷﻔﻰ ﺭﻭﻳﺎﻝ ﺣﻳﺎﺓ Royale Hayat Hospital Jabriya 25360000 25360001 ﻣﺳﺗﺷﻔﻰ ﻋﺎﻟﻳﺔ ﺍﻟﺩﻭﻟﻲ Alia International Hospital Mahboula 22272000 23717020 ﻣﺳﺗﺷﻔﻰ ﺳﺩﺭﺓ Sidra Hospital Al Reggai 24997000 24997070 1881122 ﻣﺳﺗﺷﻔﻰ ﺍﻟﺳﻳﻑ Al Seef Hospital Salmiya 25719810 25764000 25747590 ﻣﺳﺗﺷﻔﻰ ﺍﻟﻣﻭﺍﺳﺎﺓ ﺍﻟﺟﺩﻳﺩ New Mowasat Hospital Salmiya 25726666 25738055 25529012 ﻣﺳﺗﺷﻔﻰ ﻁﻳﺑﺔ Taiba Hospital Sabah Al-Salem 1808088 25528693 ﻣﺳﺗﺷﻔﻰ ﺍﻟﻛﻭﻳﺕ Kuwait Hospital Sabah Al-Salem 22207777 ﻣﺳﺗﺷﻔﻰ ﻭﺍﺭﺓ Wara Hospital Sabah Al-Salem 1888001 ﺍﻟﻣﺳﺗﺷﻔﻰ ﺍﻟﺩﻭﻟﻲ International Hospital Salmiya 1817771 This network is subject to continuous revision by addition/deletion of provider(s) and/or inclusion/exclusion of doctor(s)/department(s) Page 1 of 23 GlobeMed Kuwait Network of HealthCare Providers As of June 2021 Phone ﺍﻻﺳﻡ ProviderProvider Name Name Region Region Phone Number FaxFax Number Number Medical Centers ﻣﺳﺗﻭﺻﻑ ﻣﻳﺩﻳﻛﺎﻝ ﻭﻥ ﺍﻟﺗﺧﺻﺻﻲ Medical one Polyclinic Al Da'iyah 22573883 22574420 1886699 ﻋﻳﺎﺩﺓ ﻧﻭﺭ Noor Clinic Al Ageila 23845957 23845951 22620420 ﻣﺭﻛﺯ ﺍﻟﺷﻌﺏ ﺍﻟﺗﺧﺻﺻﻲ -

Read the Correspondent Article

Winter 2015 SILENT KILLER DR. KAZEM BEHBEHANI ON THE FIGHT CAPITAL ASSETS AGAINST DIABETES BANKING DOYENNE BY ROYAL APPOINTMENT NEMAT SHAFIK LYNNE DAVIS ON EMINENT BRITISH PRINTERS BARNARD & WESTWOOD CULTURE CLASH BARUCH SPIEGEL RETHINKING SPECIAL NEEDS EDUCATION IN KUWAIT OUTER SPACES SALMAN ZAFAR EXTOLLS THE NEED FOR GREEN UTZON UNTOLD KUWAIT NATIONAL ASSEMBLY: THE MAKING OF A MASTERPIECE IN CONVERSATION HaIlIng from a DanIsh desIgn dynasty, Jan Utzon speaks to Charlotte Shalgosky about workIng wIth hIs father, the globally-recognIzed Jørn Utzon, on hIs desIgn of the KuwaIt NatIonal Assembly. Jan Utzon greets me warmly, even and environmental sympathies in his native Denmark he is strikingly most eloquently; a building that, tall. Looking much younger than his when it frst opened, epitomized seventy-plus years his limber frame the simplicity and the sensitivity of and sparkling eyes are remarkably Utzon’s understated brilliance as reminiscent of his father, Jørn, much as his love of the Middle East. with whom he worked so closely Even before it was completed, the throughout his life. late British architectural critic Stephen Gardiner wrote “When fnished, it Jørn Utzon died in 2008 having won will be one of the great buildings almost every architectural prize of the world”. and accolade, and having been lauded for his visionary designs. In 1968, when the competition Columbia University Professor, to design the Kuwait National Kenneth Frampton, wrote in the Assembly was being held, Jan Harvard Design Magazine “Nobody was just starting out on his own can study the future of architecture career in architecture in Denmark; without Jørn Utzon”. -

4 2828226 Dubai Casablanca Road

GEMS GCC NETWORK UNITED ARAB EMIRATES CONTACT DETAILS PROVIDER NAME SPECIALITY TEL NO FAX NO AREA ADDRESS HOSPITALS Mediclinic Welcare Hospital Multispeciality (+971) 4 2827788 (+971) 4 2828226 Dubai Casablanca Road, Next To Millennium Airport Hotel, Garhoud Mediclinic City Hospital Multispeciality (+971) 4 4359999 (+971) 4 4359900 Dubai Building # 37, Behind Wafi City, Oud Metha Road, Dubai Healthcare City Canadian Specialist Hospital Multispeciality (+971) 4 7072895 (+971) 4 7072880 Dubai Behind Ramada Continental Hotel, Abu Hail Road Belhoul European Hospital.Llc Multispeciality (+971) 4 2733333 (+971) 4 2733332 Dubai Al-Khaleej Road, Al Baraha International Modern Hospital Multispeciality (+971) 4 4063521 (+971) 4 3988444 Dubai Sheikh Rashid Road, Near Port Rashid Signal, Beside Chelsea Hotel, Bur Dubai Neuro Spinal Hospital Multispeciality (+971) 4 3420000 (+971) 4 3420007 Dubai Opposite Jumeirah Beach Park, Jumeirah Beach Road, Jumeirah Aster Hospital Multispeciality (+971) 43552321 (+971) 43552321 Dubai Mankhool, AL Rafa St. Burdubai, DXB Moorefields Eye Hospital Dubai Multispeciality (+971) 4 429 7888 (+971) 4 363 5339 Dubai Al Razi Building 64, Block E, Floor 3, Dubai Healthcare City, Dubai, UAE MEDICAL CENTERE/ POLYCLINIC/CLINICS Better Life Clinic Multispeciality (+971) 4 3592255 (+971) 4 3528249 Dubai Flatno:203-Al Tawhidi 2 Building Next To Ramada Hotel , Al Mankool Road Al-Mousa Medical Centre Multispeciality (+971) 4 3452999 (+971) 4 3452802 Dubai Al Wasl Road, Jumeirah - 332 Ideal Diagnostic Centre Multispeciality (+971) 4 3979255 (+971) 4 3979256 Dubai Office103 Khalid Al Attar Bldg. Opposite Bargeman Panacea Medical Centre New Multispeciality (+971) 4 3582020 (+971) 4 3582121 Dubai Easa Saleh Al Gurg Building, Tariq Bin Ziyad Road, Umm Hurair Keerti Medical Center Multispeciality (+971) 4 3344256 (+971) 4 3348158 Dubai Karama - Al Attar Shopping Mall, Next To Karama Centre Dr. -

Bazaar Profile

PROFILE 30,000+160,000 +50,000+20,000 Print Media Readers Monthly website visitors Social media/newsletter Digital issue readers fans + followers MONTHLY TOUCH POINTS WITH =260,000 YOUR FUTURE CUSTOMERS 1 bazaar Culture A BROAD GROUP OF bazaar is a lifestyle magazine for the influential, AVERAGE AGE creative, young-at-heart professional. ARAB EXPAT AFFLUENCE THE RIGHT POTENTIAL Catering to both English and Arabic readers, we have + + = CUSTOMERS SEEING more than 75 freelance writers. OF READER YOUR PRODUCT 85 % Un ive rsity Established in 1997, bazaar’s brand and personality is 30 ye a rs o ld 65 % 35 % G radu ates unique to Kuwait. - One of the most influential magazines in Kuwait. - Distributed, free of charge, in over 250 retail, fashion 1997 2006 and dining outlets. - Online reach at www.bazaar.town with over 160,000 2002 visitors a month. Published every month of the year, with a special combined July/August issue. 2013 2015 bazaar Readers Loyal and brand savvy, worldly, free-thinking, consumers who love to travel and enjoy a mid to high class lifestyle. Mainly English-speaking Arab expats who: - Think and live in many languages and cultures. - Range from business owners and managers, to entertainment addicts and oddballs; we have something for everyone! Key Demographics Gender: Female: 55%; Male: 45% Nationality: Kuwaiti: 65%; Expat: 35% Age: 18 – 45 (bazaar has something for everyone!) Education: Over 85% University graduates 2014 Guarantee of distribution throughout Kuwait One of the first and only publications to apply for a BPA publishing audit in Kuwait to ensure total transparency. -

November 19-21, 2019 the Sheikh Jaber Al Ahmad Cultural Centre

7th INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON ENERGY RESEARCH & DEVELOPMENT (ICERD-7) November 19-21, 2019 The Sheikh Jaber Al Ahmad Cultural Centre-Conference Halls 25 Jamal Abdul Nasser St, Kuwait City, Kuwait Organizers: Sponsors: Table Contents State of Kuwait .................................................................................................................... 3 Address by the Chairman of the Organizing Committee .................................................... 4 General Information about the Conference ....................................................................... 5 Conference Organization ..................................................................................................... 6 Keynote Speakers ................................................................................................................ 8 Schedule Overview ............................................................................................................ 14 Pre-conference Courses and Workshops: ......................................................................... 16 Day 1 - Tuesday November 19, 2019 ................................................................................ 17 Day 2 - Wednesday November 20, 2019 ........................................................................... 20 Day 3 - Thursday November 21, 2019 ............................................................................... 23 Author Index ..................................................................................................................... -

P30-31 Layout 1

WHAT’S ON THURSDAY, NOVEMBER 12, 2015 Gulf operetta depicts unity of Gulf countries: Sheikh Salman Gulf operetta, dubbed “Khaleej Al-Nour,” depicts nation- al unity and common destiny binding people of the AArabian Gulf countries, Minister of Information and Minister of State for Youth Affairs Sheikh Salman Al-Sabah said. Sheikh Salman, representing His Highness the Crown Prince Sheikh Nawaf Al-Ahmad Al-Jaber Al-Sabah at the open- ing of the Operetta Tuesday evening, said Khaleej Al-Nour conveyed a message of love from the Kuwaiti people to the leaders of the Gulf countries “whose wisdom contributed to preserve security of our countries from threats.” Sheikh Salman expressed content that the operetta coin- cided with the 53th anniversary of Kuwait’s Constitution, which was a roadmap for relations between the political lead- ership and people. The constitution, he said, prevented many crises. Amiri Diwan Advisor Mohammad Sharar said the youth artifacts exhibition would be moved to Sheikh Sabah Al- Ahmad Traditional Village. He said in a statement these cultur- al festivals would further boost relations among the Gulf peo- ples. Dr. Humoud Fulaiteh, Chairman of the operetta organizing committee, said Khaleej Al-Nour was depicting the past and present of the Gulf region, and how youth were contributing to social and economic development. Fulaiteh, also Deputy Director General of the Public Authority for Sport, said the youth should take the lead in development and innovation. — KUNA Get Ready to Walk or Run ‘Gulf Bank 642 Marathon’ Commercial Bank Marathon starts 8am at Souq Sharq Saturday sponsors 360 Mall marathon uwait is set to witness its first full road race on Saturday, represented at the race, and we have people coming in from Kuwait. -

AACANVAS Represented By: Essa Muhammad|

Alymamah Rashed [email protected] | www.alymamahrashed | @AACANVAS Represented by: Essa Muhammad| https://www.essamuhammad.com/ Education Parsons School of Design, MFA Fine Arts (expected to graduate in May 2019) 2017 -2019 School of Visual Arts, New York, NY 2012- 2016 BFA Fine Arts (Painting) Honors & Awards Masters Academic Scholarship, Kuwait Ministry of Higher Education 2017-2019 Professional DeVelopment InitiatiVe Program Fellow, 2016-2017 sponsored by: National U.S-Arab Chamber of Commerce Kuwait Ministry of Higher Education Embassy of the State of Kuwait in Washington Kuwait Foundation for the AdVancement of Sciences Certificate of Academic Merit, Kuwait Ministry of Higher Education 2012 - 2016 School of Visual Arts Deans List 2012-2016 Merit Scholarship, Kuwait Ministry of Higher Education 2012-2016 Publications “The Metaphoric Phases of my CollectiVe Body as a Muslima Cyborg” by Alymamah Rashed, Published by Saalt Press May 2020 Curatorial Brief and Catalogue for Mohamed AL Hemd’s “Halal Nights” Exhibition at CAP Gallery, Kuwait 2019 Featured in Tsquare Magazine Issue #23 2019 Featured in The Beyond Mag Issue 2 2019 Featured in “ConVergence” Catalogue curated by Utsa Hazarika 2018 Featured in Sumou Magazine Issue 00 “All The Things We Don’t Feel” 2018 Featured in Air Sheets Publication by Sorry ArchiVe 2017 Designed and illustrated a book cover for Bader Al Sanousi’s Publication 2017 (My Mind Made You Beautiful), Kuwait 2015 Experience Kuwait UniVersity – College of Architecture (Visual Communication Dept) Part Time