Comparative Geomatic Analysis of Historic Development, Trends, And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Interregional Interaction and Dilmun Power

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 4-7-2014 Interregional Interaction and Dilmun Power in the Bronze Age: A Characterization Study of Ceramics from Bronze Age Sites in Kuwait Hasan Ashkanani University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Scholar Commons Citation Ashkanani, Hasan, "Interregional Interaction and Dilmun Power in the Bronze Age: A Characterization Study of Ceramics from Bronze Age Sites in Kuwait" (2014). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/4980 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Interregional Interaction and Dilmun Power in the Bronze Age: A Characterization Study of Ceramics from Bronze Age Sites in Kuwait by Hasan J. Ashkanani A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Anthropology College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Robert H. Tykot, Ph.D. Thomas J. Pluckhahn, Ph.D. E. Christian Wells, Ph.D. Jonathan M. Kenoyer, Ph.D. Jeffrey Ryan, Ph.D. Date of Approval April 7, 2014 Keywords: Failaka Island, chemical analysis, pXRF, petrographic thin section, Arabian Gulf Copyright © 2014, Hasan J. Ashkanani DEDICATION I dedicate my dissertation work to the awaited savior, Imam Mohammad Ibn Al-Hasan, who appreciates knowledge and rejects all forms of ignorance. -

Tentative Lists Submitted by States Parties As of 15 April 2021, in Conformity with the Operational Guidelines

World Heritage 44 COM WHC/21/44.COM/8A Paris, 4 June 2021 Original: English UNITED NATIONS EDUCATIONAL, SCIENTIFIC AND CULTURAL ORGANIZATION CONVENTION CONCERNING THE PROTECTION OF THE WORLD CULTURAL AND NATURAL HERITAGE WORLD HERITAGE COMMITTEE Extended forty-fourth session Fuzhou (China) / Online meeting 16 – 31 July 2021 Item 8 of the Provisional Agenda: Establishment of the World Heritage List and of the List of World Heritage in Danger 8A. Tentative Lists submitted by States Parties as of 15 April 2021, in conformity with the Operational Guidelines SUMMARY This document presents the Tentative Lists of all States Parties submitted in conformity with the Operational Guidelines as of 15 April 2021. • Annex 1 presents a full list of States Parties indicating the date of the most recent Tentative List submission. • Annex 2 presents new Tentative Lists (or additions to Tentative Lists) submitted by States Parties since 16 April 2019. • Annex 3 presents a list of all sites included in the Tentative Lists of the States Parties to the Convention, in alphabetical order. Draft Decision: 44 COM 8A, see point II I. EXAMINATION OF TENTATIVE LISTS 1. The World Heritage Convention provides that each State Party to the Convention shall submit to the World Heritage Committee an inventory of the cultural and natural sites situated within its territory, which it considers suitable for inscription on the World Heritage List, and which it intends to nominate during the following five to ten years. Over the years, the Committee has repeatedly confirmed the importance of these Lists, also known as Tentative Lists, for planning purposes, comparative analyses of nominations and for facilitating the undertaking of global and thematic studies. -

PRIVATE HOUSING MURSHID 2014 Brief on Real Estate Union

PRIVATE HOUSING MURSHID 2014 Brief on Real Estate Union Real Estate Association was established in 1990 by a distinguished group headed by late Sheikh Nasser Saud Al-Sabah who exerted a lot of efforts to establish the Association. Bright visionary objectives were the motives to establish the Association. The Association works to sustainably fulfil these objectives through institutional mechanisms, which provide the essential guidelines and controls. The Association seeks to act as an umbrella gathering the real estate owners and represent their common interests in the business community, overseeing the rights of the real estate professionals and further playing a prominent role in developing the real estate sector to be a major and influential player in the economic decision-making in Kuwait. The Association also offers advisory services that improve the real estate market in Kuwait and enhance the safety of the real estate investments, which result in increasing the market attractiveness for more investment. The Association considers as a priority keeping the investment interests of its members and increase the membership base to include all owners segments of the commercial and investment real estate. Summary Private housing segment is the single most important segment of real estate industry in Kuwait. The land parcels zoned for private housing account for 78% of all land parcels in Kuwait and the segment is the main source of wealth (as family houses) for most of the households. This report is written with an objective to provide a comprehensive analysis of this segment with the historical trends of prices, rental activities, and impact of land features on property prices. -

Real Estate Guidance 2017 1 Index

Real Estate Guidance 2017 1 Index Brief on Real Estate Union 4 Executive Summary 6 Investment Properties Segment 8 Freehold Apartments Segment 62 Office Space Segment 67 Retail Space Segment 72 Industrial Segment 74 Appendix 1: Definition of Terms Used in the Report 76 Appendix 2: Methodology of Grading of Investment Properties 78 2 3 BRIEF ON REAL ESTATE UNION Real Estate Association was established in 1990 by a distinguished group headed by late Sheikh Nasser Saud Al-Sabahwho exerted a lot of efforts to establish the Association. Bright visionary objectives were the motives to establishthe Association. The Association works to sustainably fulfil these objectives through institutional mechanisms, whichprovide the essential guidelines and controls. The Association seeks to act as an umbrella gathering the real estateowners and represent their common interests in the business community, overseeing the rights of the real estateprofessionals and further playing a prominent role in developing the real estate sector to be a major and influentialplayer in the economic decision-making in Kuwait. The Association also offers advisory services that improve the real estate market in Kuwait and enhance the safety ofthe real estate investments, which result in increasing the market attractiveness for more investment. The Association considers as a priority keeping the investment interests of its members and increase the membershipbase to include all owners segments of the commercial and investment real estate. This publication is supported by kfas and Wafra real estate 4 Executive Summary Investment Property Segment • For the analysis of the investment properties market, we have covered 162,576 apartments that are spread over 5,695 properties across 19 locations in Kuwait. -

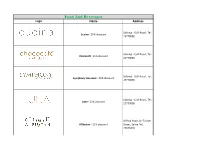

Food and Beverages Logo Name Address

Food And Beverages Logo Name Address Salmiya - Gulf Road , Tel: Cucina - 25% discount 25770000 Salmiya - Gulf Road , Tel: Chococafe- 25% discount 25770000 Salmiya - Gulf Road , Tel: Symphony Gourmet - 25% discount 25770000 Salmiya - Gulf Road , Tel: Luna - 25% discount 25770000 Al Bida Road, Al -Ta'awn Al Bustan - 25% discount Street, Salwa Tel: 25673410 Al Bida Road, Al -Ta'awn Eedam - 25% discount on homemade items only Street, Salwa Tel: 25673420 Al Bida Road, Al -Ta'awn Al Boom - 25% discount Street, Salwa Tel: 25673430 Al Bida Road, Al -Ta'awn Peacock - 25% discount during lunch only Street, Salwa Tel: 25673440 Marina mall / liwan/ the Nestle Toll House café - 15% discount village / Levels Tel : 22493773 Sharq, Al Hamra luxury Sushi bar - 12% discount center, 1st floor Sharq, Al Hamra luxury Versus Varsace Café - 12% discount center, 1st floor The Village, Kipco Tower Upper Crust - 10% discount Sharq Tel : 1821872 Murooj Sabhan Tel : Crumbs - 10% discount 22050270 Dar Al Awadhi, Kuwait Munch - 10% discount City Tel : 22322747 Gulf Road, Across from Mais Al Ghanim - 10% discount Kuwait Towers, Spoons Complex Tel: 22250655 Bneid Al gar - Al bastaki Mawal Lebnan Café & Restaurant - 15% discount hotel - 14th floor Tel : 22575169 Miral complex Tel : Debs Al reman - 15% Discount 22493773 Avenues Mall Tel : Boccini Pizzeria - 15% discount 22493773 Salmiya, Salem Mubarak ibis Hotel Restaurants- 20% discount Street and Sharq Tel : 25713872 Salmiya, Tel: 25742090- Dag Ayoush- 15% discount 55407179 Salmiya salem almubarak street - Basbakan- -

Semantic Innovation and Change in Kuwaiti Arabic: a Study of the Polysemy of Verbs

` Semantic Innovation and Change in Kuwaiti Arabic: A Study of the Polysemy of Verbs Yousuf B. AlBader Thesis submitted to the University of Sheffield in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the School of English Literature, Language and Linguistics April 2015 ABSTRACT This thesis is a socio-historical study of semantic innovation and change of a contemporary dialect spoken in north-eastern Arabia known as Kuwaiti Arabic. I analyse the structure of polysemy of verbs and their uses by native speakers in Kuwait City. I particularly report on qualitative and ethnographic analyses of four motion verbs: dašš ‘enter’, xalla ‘leave’, miša ‘walk’, and i a ‘run’, with the aim of establishing whether and to what extent linguistic and social factors condition and constrain the emergence and development of new senses. The overarching research question is: How do we account for the patterns of polysemy of verbs in Kuwaiti Arabic? Local social gatherings generate more evidence of semantic innovation and change with respect to the key verbs than other kinds of contexts. The results of the semantic analysis indicate that meaning is both contextually and collocationally bound and that a verb’s meaning is activated in different contexts. In order to uncover the more local social meanings of this change, I also report that the use of innovative or well-attested senses relates to the community of practice of the speakers. The qualitative and ethnographic analyses demonstrate a number of differences between friendship communities of practice and familial communities of practice. The groups of people in these communities of practice can be distinguished in terms of their habits of speech, which are conditioned by the situation of use. -

Study of Change Detection in Urban Growth of Kuwait City

International Journal of Environmental Science and Development, Vol. 10, No. 5, May 2019 Study of Change Detection in Urban Growth of Kuwait City Fahad Almutairi and Mohamed Ait Belaid techniques for better results. Abstract—Kuwait City has witnessed rapid urban The process of identifying and detecting change in land development, with a clear change in land use in Kuwait City use (change detection) over a period of time of recent during the last period. In the second half of the twentieth processes and trends, and the knowledge of urban growth century, Kuwait witnessed an urban development due to the helps to understand and analyze patterns of land use, and economic boom and the discovery of oil. This development is accompanied by a huge increase in the number of residents and factors affecting them [1]. Incoming; Resulting in an increase in economic and urban activities, and one of the most affected areas of Kuwait City. This research aims to study the urban growth of Kuwait City I. DETERMINE THE STUDY AREA using aerial photographs and high-resolution satellite imagery. The city of Kuwait is located within the cities and suburbs The study is based on the first two aerial photographs for the of the Capital Governorate. The study area is located between years 1976 with a spatial resolution of 1.5 meters and the second two latitudes (30 '21 ° 29 'and 30 °' 29 °) north of the equator for 1991 with a spatial resolution of 60 cm and two satellite imagery (IKONOS) for 2000 by 1 meter and the second for the and between longitude (30 '57 ° 47 'and 20' 0 ° 48) east of satellite (WorldView-2) for 2011 at 50 cm. -

Al Koot Kuwait Provider Network

AlKoot Insurance & Reinsurance Partner Contact Details: Kuwait network providers list Partner name: Globemed Tel: +961 1 518 100 Email: [email protected] Agreement type Provider Name Provider Type Provider Address City Country Partner Al Salam International Hospital Hospital Bnaid Al Gar Kuwait City Kuwait Partner London Hospital Hospital Al Fintas Kuwait City Kuwait Partner Dar Al Shifa Hospital Hospital Hawally Kuwait City Kuwait Partner Al Hadi Hospital Hospital Jabriya Kuwait City Kuwait Partner Al Orf Hospital Hospital Al Jahra Kuwait City Kuwait Partner Royale Hayat Hospital Hospital Jabriyah Kuwait City Kuwait Partner Alia International Hospital Hospital Mahboula Kuwait City Kuwait Partner Sidra Hospital Hospital Al Reggai Kuwait City Kuwait Partner Al Rashid Hospital Hospital Salmiya Kuwait City Kuwait Partner Al Seef Hospital Hospital Salmiya Kuwait City Kuwait Partner New Mowasat Hospital Hospital Salmiya Kuwait City Kuwait Partner Taiba Hospital Hospital Sabah Al-Salem Kuwait City Kuwait Partner Kuwait Hospital Hospital Sabah Al-Salem Kuwait City Kuwait Partner Medical One Polyclinic Medical Center Al Da'iyah Kuwait City Kuwait Partner Noor Clinic Medical Center Al Ageila Kuwait City Kuwait Partner Quttainah Medical Center Medical Center Al Shaab Al Bahri Kuwait City Kuwait Partner Shaab Medical Center Medical Center Al Shaab Al Bahri Kuwait City Kuwait Partner Al Saleh Clinic Medical Center Abraq Kheetan Kuwait City Kuwait Partner Global Medical Center Medical Center Benaid Al qar Kuwait City Kuwait Partner New Life -

Y-Chromosome & Mitochondrial DNA Variation

The Genetic Structure of the Kuwaiti and Failaka Island Populations: Y-chromosome & Mitochondrial DNA Variation By Jasem Bader Theyab M.A., University of Kansas, 2010 Copyright 2013 Submitted to the graduate degree program in Anthropology and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ________________________________ Chairperson, Dr. Michael H. Crawford ________________________________ Dr. Majid Hannoum ________________________________ Dr. Deborah Smith ________________________________ Dr. Bartholomew C. Dean ________________________________ Dr. John Kelly Date Defended: May 28, 2013 The Dissertation Committee for Jasem Bader Theyab certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: The Genetic Structure of the Kuwaiti and Failaka Island Populations: Y-chromosome & Mitochondrial DNA Variation ________________________________ Chairperson, Dr. Michael H. Crawford Date approved: May 31, 2013 ii Abstract Recent studies applying multidisciplinary approaches suggest that the Anatomically Modern Homo sapiens (AMHS) passed through the Arabian Peninsula in their major diaspora out of Africa. The Arabian Peninsula is connected to three continents: Africa, Asia, and Europe. In addition to the major diaspora, the Arabian Peninsula has witnessed numerous migrations among the three continents. The populations of the Arabian Peninsula have been investigated to better understand their evolutionary history. This dissertation investigated the paternal genetic structure of the Kuwaiti and Failaka Island populations using 15 loci Y-STR data. In addition, the maternal genetic structure of Failaka Island has been investigated using mtDNA HVS-I sequence data. This is the first genetic study to characterize Failaka Island population. The result showed that the Kuwaiti population has a high frequency of Y- haplogroup J1 (37%) similar to other Arabian populations. -

Globemed Kuwait Network of Providers Exc KSEC and BAYAN

GlobeMed Kuwait Network of HealthCare Providers As of June 2021 Phone ﺍﻻﺳﻡ ProviderProvider Name Name Region Region Phone Number FFaxax Number Number Hospitals 22573617 ﻣﺳﺗﺷﻔﻰ ﺍﻟﺳﻼﻡ ﺍﻟﺩﻭﻟﻲ Al Salam International Hospital Bnaid Al Gar 22232000 22541930 23905538 ﻣﺳﺗﺷﻔﻰ ﻟﻧﺩﻥ London Hospital Al Fintas 1 883 883 23900153 22639016 ﻣﺳﺗﺷﻔﻰ ﺩﺍﺭ ﺍﻟﺷﻔﺎء Dar Al Shifa Hospital Hawally 1802555 22626691 25314717 ﻣﺳﺗﺷﻔﻰ ﺍﻟﻬﺎﺩﻱ Al Hadi Hospital Jabriya 1828282 25324090 ﻣﺳﺗﺷﻔﻰ ﺍﻟﻌﺭﻑ Al Orf Hospital Al Jahra 2455 5050 2456 7794 ﻣﺳﺗﺷﻔﻰ ﺭﻭﻳﺎﻝ ﺣﻳﺎﺓ Royale Hayat Hospital Jabriya 25360000 25360001 ﻣﺳﺗﺷﻔﻰ ﻋﺎﻟﻳﺔ ﺍﻟﺩﻭﻟﻲ Alia International Hospital Mahboula 22272000 23717020 ﻣﺳﺗﺷﻔﻰ ﺳﺩﺭﺓ Sidra Hospital Al Reggai 24997000 24997070 1881122 ﻣﺳﺗﺷﻔﻰ ﺍﻟﺳﻳﻑ Al Seef Hospital Salmiya 25719810 25764000 25747590 ﻣﺳﺗﺷﻔﻰ ﺍﻟﻣﻭﺍﺳﺎﺓ ﺍﻟﺟﺩﻳﺩ New Mowasat Hospital Salmiya 25726666 25738055 25529012 ﻣﺳﺗﺷﻔﻰ ﻁﻳﺑﺔ Taiba Hospital Sabah Al-Salem 1808088 25528693 ﻣﺳﺗﺷﻔﻰ ﺍﻟﻛﻭﻳﺕ Kuwait Hospital Sabah Al-Salem 22207777 ﻣﺳﺗﺷﻔﻰ ﻭﺍﺭﺓ Wara Hospital Sabah Al-Salem 1888001 ﺍﻟﻣﺳﺗﺷﻔﻰ ﺍﻟﺩﻭﻟﻲ International Hospital Salmiya 1817771 This network is subject to continuous revision by addition/deletion of provider(s) and/or inclusion/exclusion of doctor(s)/department(s) Page 1 of 23 GlobeMed Kuwait Network of HealthCare Providers As of June 2021 Phone ﺍﻻﺳﻡ ProviderProvider Name Name Region Region Phone Number FaxFax Number Number Medical Centers ﻣﺳﺗﻭﺻﻑ ﻣﻳﺩﻳﻛﺎﻝ ﻭﻥ ﺍﻟﺗﺧﺻﺻﻲ Medical one Polyclinic Al Da'iyah 22573883 22574420 1886699 ﻋﻳﺎﺩﺓ ﻧﻭﺭ Noor Clinic Al Ageila 23845957 23845951 22620420 ﻣﺭﻛﺯ ﺍﻟﺷﻌﺏ ﺍﻟﺗﺧﺻﺻﻲ -

Indicators of Urban Health in the Youth Population of Kuwait City and Jahra, Kuwait

Indicators of urban health in the youth population of Kuwait City and Jahra, Kuwait Fayez Alzarban A thesis submitted to the University of Liverpool for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Public Health) at the Faculty of Health and Life Sciences March: 2018 Declaration No portion of the work in this thesis has been submitted in support of an application for any degree or qualification of the University of Liverpool or any other University or institute of learning. Signature Acknowledgements I would like to start by thanking my outstanding supervisors at the University of Liverpool: Dr. Daniel Pope and Dr. Debbi Stanistreet, for their constant support, dedication, and encouragement throughout my study period. I am also grateful for all the help I have received from my academic advisors allocated by the Postgraduate team: Prof. Dame Margaret Whitehead, Prof. Sally Sheard, Prof. David Taylor- Robinson, and Prof. Martin O’Flaherty, for all the advice and guidance they have given me. I would also like to thank Prof. Susan Higham for tremendous support at a very difficult period during my studies. In Kuwait, I would like to extend my thanks to Dr. Jafaar Dawood, the head of the Department of Public Health at the Ministry of Health (Kuwait), for his support in every step of this research in Kuwait. Without his exceptional efforts, this project would have not been possible. I would also like to thank the health inspectors at the Department of Health (Kuwait) for their generosity and dedication in conducting the survey with me: Basim Awkal, MS. Allimby, Ala’a Jaad, Saleh Mohammed, Michelle Asaad, Sarah Alazmi, and Hesa Alali. -

Downloads/2003 Essay.Pdf, Accessed November 2012

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Nation Building in Kuwait 1961–1991 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/91b0909n Author Alomaim, Anas Publication Date 2016 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Nation Building in Kuwait 1961–1991 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Architecture by Anas Alomaim 2016 © Copyright by Anas Alomaim 2016 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Nation Building in Kuwait 1961–1991 by Anas Alomaim Doctor of Philosophy in Architecture University of California, Los Angeles, 2016 Professor Sylvia Lavin, Chair Kuwait started the process of its nation building just few years prior to signing the independence agreement from the British mandate in 1961. Establishing Kuwait’s as modern, democratic, and independent nation, paradoxically, depended on a network of international organizations, foreign consultants, and world-renowned architects to build a series of architectural projects with a hybrid of local and foreign forms and functions to produce a convincing image of Kuwait national autonomy. Kuwait nationalism relied on architecture’s ability, as an art medium, to produce a seamless image of Kuwait as a modern country and led to citing it as one of the most democratic states in the Middle East. The construction of all major projects of Kuwait’s nation building followed a similar path; for example, all mashare’e kubra [major projects] of the state that started early 1960s included particular geometries, monumental forms, and symbolic elements inspired by the vernacular life of Kuwait to establish its legitimacy.