Linkas Keisis Instructions for Authors

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Of the 90 YEARS of the RAAF

90 YEARS OF THE RAAF - A SNAPSHOT HISTORY 90 YEARS RAAF A SNAPSHOTof theHISTORY 90 YEARS RAAF A SNAPSHOTof theHISTORY © Commonwealth of Australia 2011 This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission. Inquiries should be made to the publisher. Disclaimer The views expressed in this work are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of Defence, the Royal Australian Air Force or the Government of Australia, or of any other authority referred to in the text. The Commonwealth of Australia will not be legally responsible in contract, tort or otherwise, for any statements made in this document. Release This document is approved for public release. Portions of this document may be quoted or reproduced without permission, provided a standard source credit is included. National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry 90 years of the RAAF : a snapshot history / Royal Australian Air Force, Office of Air Force History ; edited by Chris Clark (RAAF Historian). 9781920800567 (pbk.) Australia. Royal Australian Air Force.--History. Air forces--Australia--History. Clark, Chris. Australia. Royal Australian Air Force. Office of Air Force History. Australia. Royal Australian Air Force. Air Power Development Centre. 358.400994 Design and layout by: Owen Gibbons DPSAUG031-11 Published and distributed by: Air Power Development Centre TCC-3, Department of Defence PO Box 7935 CANBERRA BC ACT 2610 AUSTRALIA Telephone: + 61 2 6266 1355 Facsimile: + 61 2 6266 1041 Email: [email protected] Website: www.airforce.gov.au/airpower Chief of Air Force Foreword Throughout 2011, the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) has been commemorating the 90th anniversary of its establishment on 31 March 1921. -

Casualty Week Aug 11

Lloyd’s Casualty Week contains information from worldwide sources of Marine, Non-Marine and Aviation casualties together with other reports Lloyd's relevant to the shipping, transport and insurance communities CasualtyWeek Aug 11 2006 Cloud over Hong Kong storm signal system Observatory attacked over typhoon response, writes Keith Wallis- Monday August 07 2006 HE Hong Kong Observatory will Fast ferries between Hong Kong and signal 3 meaning sustained wind speeds of review its storm signal system after a Macau and cities in southern China were later between 41 and 62 kmph in Victoria Harbour Tbarrage of criticism following its suspended, trapping hundreds of passengers, throughout Thursday. response to winds generated by typhoon while more than 90 seafarers on two Chinese This was despite wind speeds of 209 Prapiroon. barges were rescued by Hong Kong kmph being recorded at Ngong Ping, close to The observatory kept its storm signal at government helicopters. Hong Kong International Airport, and 108 typhoon 3 last Thursday, meaning it was safe There was also property damage with the kmph at Tsing Yi near Kwai Chung container to go to work and for ferries to keep windows blown out of several offices port. operating. including those at shipbroker Simpson Responding to the complaints the This was despite winds gusting at more Spence and Young. observatory confirmed it would reassess the than 200 kmph which causing flight chaos at In the Lloyd’s List office, which is in the way storm signals were evaluated to improve Hong Kong International Airport, property same building as SSY, the differential air the system. -

TEED!* * Find It Lower? We Will Match It

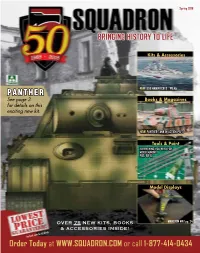

Spring 2018 BRINGING HISTORY TO LIFE Kits & Accessories NEW! USS HAWAII CB-3 PG.45 PANTHER See page 3 Books & Magazines for details on this exciting new kit. NEW! PANTHER TANK IN ACTION PG. 3 Tools & Paint EVERYTHING YOU NEED FOR MODELMAKING PGS. 58-61 Model Displays OVER 75 NEW KITS, BOOKS MARSTON MAT pg. 24 LOWEST PRICE GUARANTEED!* & ACCESSORIES INSIDE! * * See back cover for full details. Order Today at WWW.SQUADRON.COM or call 1-877-414-0434 Dear Friends, Now that we’ve launched into daylight savings time, I have cleared off my workbench to start several new projects with the additional evening light. I feel really motivated at this moment and with all the great new products we have loaded into this catalog, I think it is going to be a productive spring. As the seasons change, now is the perfect time to start something new; especially for those who have been considering giving the hobby a try, but haven’t mustered the energy to give it a shot. For this reason, be sure to check out pp. 34 - our new feature page especially for people wanting to give the hobby a try. With products for all ages, a great first experience is a sure thing! The big news on the new kit front is the Panther Tank. In conjunction with the new Takom (pp. 3 & 27) kits, Squadron Signal Publications has introduced a great book about this fascinating piece of German armor (SS12059 - pp. 3). Author David Doyle guides you through the incredible history of the WWII German Panzerkampfwagen V Panther. -

U.S. Naval Sea Cadet Corps Battleship Utah (BB-31) Division Commanding Officer: LTJG M

U.S. Naval Sea Cadet Corps Battleship Utah (BB-31) Division Commanding Officer: LTJG M. J. Sowell, USNSCC Executive Officer: WO J. Guggenheim, USNSCC Command Chief: CPO S. Ochoa “ALL PERSONNEL SHALL READ THE “PLAN OF THE MONTH” AND SHALL BE RESPONSIBLE FOR OBEYING ALL APPLICABLE ORDERS CONTAINED HEREIN. DIRECTIVES APPEARING HEREIN HAVE THE FULL FORCE OF ORDERS ISSUED BY THE COMMANDING OFFICER.” Commanding Officer LTJG Sowell (801) 654-6568 [email protected] Executive Officer WO Guggenheim (801) 793-1790 [email protected] ESO ENS Russon (801) 209-3213 [email protected] Recruiting WO Guggenheim (801) 793-1790 [email protected] Admin.Officer LPO CPO S. Ochoa [email protected] Training Ship - NLCC LTJG Sowell (435) 654-6568 [email protected] Supply ENS Bodily (435) 232-0435 [email protected] PLAN OF THE MONTH For the Day of 14/15 OCT 2017 BE PROUD BE PROFESSIONAL DATE Muster Release Uniform of the Day 14 OCT 2017 0730 1500 Cadets Officers and CPO NWUs / PT P/ NWUs A/Service Khakis 15 OCT 2017 0730 1500 Cadets Officers and CPO NWUs /PT P/ NWUs A/ Service Khakis OFFICIAL ANNOUNCEMENTS 1. Drills Dates: 11/12 NOV // 16 DEC 2. Cadets need to report their drill attendance plans to their Department LPO as soon as possible. 3. Report to drill in your PT Gear at the NOSC. 4. Cadets need to bring a lunch both days. 5. ***If your uniform is not complete, you will not wear it!*** 6. If you are behind on your coursework, bring it with you to drill and be ready to work on it during drill times. -

Mission: History Studiorum Historiam Praemium Est

N a v a l O r d e r o f t h e U n i t e d S t a t e s – S a n F r a n c i s c o C o m m a n d e r y Mission: History Studiorum Historiam Praemium Est 2 October 2000 HHHHHH Volume 2, Number 10 1943: Ranger Fights Her Only Battle Her Planes Sink 23,000 Tons of Germ an Ships Off Norwegian Coast On 4 October 1943, USS Ranger (CV-4) took part in her only action against enemy ships, and came away a winner. But she didn’t exactly put her- self in harm’s way. Ranger, commanded by Capt. Gordon Rowe, was part of a task force led by the British Home Fleet Commander in Chief, Admiral Sir Bruce Fraser, in an effort to interdict German shipping in northern waters. Fraser flew his flag in the battleship HMS Duke of York and had with him the fleet carrier HMS An- son, three cruisers and six destroyers. U.S. Rear Admiral Olaf M. Hustvedt added Ranger, the cruiser Tuscaloosa (CA-37) and a destroyer screen to Fra- ser’s force. RANGER TRANSITING PANAMA CANAL. She spent four years in the Pacific in the 1930s, and Operation LEADER, as the effort was what was learned was that she was too slow for that broad ocean. She spent most of the war on called, had as its objective the port of escort duty in the Atlantic, returning to the Pacific in the late stages of the war as a training ship. -

Bowl Round 7 Bowl Round 7 First Quarter

NHBB A-Set Bowl 2017-2018 Bowl Round 7 Bowl Round 7 First Quarter (1) This settlement was abandoned after the loss of a trade network centered on Kilwa, leading its inhabitants to settle Mutapa. Sites at this settlement include the Great Enclosure and the Hill Complex, where eight birds carved of soapstone were once supposed to have stood. It was constructed by the Shona people, who protected themselves with high walls built without mortar. For ten points, name this Iron Age settlement that lends its name to an African country with capital Harare. ANSWER: Great Zimbabwe (prompt on Zimbabwe) (2) This man was not given songwriting credit on \Never Learn Not to Love" by the Beach Boys, even though it was derived from this man's song \Cease to Exist." This man's belief in hidden messages on the Beatles' White Album inspired the idea of a \Helter Skelter" race war. One of the stars of Valley of the Dolls, Sharon Tate, was over eight months pregnant when this man's followers murdered her in 1969. For ten points, name this cult leader who died in prison in 2017. ANSWER: Charles Manson (3) A treaty with this name included the secret Act of Seclusion, by which the future William III lost the title of Stadtholder. The first and third Anglo-Dutch Wars were ended by treaties of this name. A 1931 statute of this name established protocols between the U.K. and dominion realms. A religious building with this name was built on the orders of Edward the Confessor and was the site of his burial. -

Fourapport462019.Pdf (3.966Mb)

Organizing emergency response in the European Arctic: A comparative study of Norway, Russia, Iceland and Greenland MARPART Project Report 5 Editors: Natalia Andreassen Odd Jarl Borch Emmi Ikonen Nord University R&D-Report no. 46 Bodø 2019 Organizing emergency response in the European Arctic: A comparative study of Norway, Russia, Iceland and Greenland MARPART Project Report 5 Editors: Natalia Andreassen Odd Jarl Borch Emmi Ikonen Nord University R&D-Report no. 46 ISBN 978-82-7456-812-9 ISSN 2535-2733 Bodø 2019 46 978-82-7456-812-9 2535-2733 The report is developed under the project: “MARPART” (MARITIME PREPAREDNESS AND INTERNATIONAL PARTNERSHIP IN THE HIGH NORTH), Work Package 3 “Organizations and Operational Management Structures” Project period: 2015-2018 The project is financed by: - The Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Norway - Nordland County Administration - Nord University - Project partners’ own contribution Project partners: - High North Center at Nord University Business School (Norway) - Norwegian Defense University College (Norway) - Norwegian Police University College (Norway) - UIT-the Arctic University of Norway (Norway) - University Center in Svalbard (Norway) - University of Greenland (Greenland) - University of Iceland (Iceland) - Northern (Arctic) Federal University (Russia) - Murmansk State Technical University (Russia) THE MARPART RESEARCH CONSORTIUM MARPART – a project on the management, organization and governance of cross- border collaboration on emergency operations in the High North. The key purpose of the Marpart research is to increase the understanding of the emergency management challenges in the Arctic sea areas. Our work includes an assessment of the risk related to different types of maritime activity in the High North and an overview of the responsibilities of the preparedness institutions of Norway and its neighboring countries. -

The Jerseyman Number 78

“Rest well, yet sleep lightly and hear the call, if again sounded, to provide Firepower for Freedom…” 2nd Quarter 2013 The Jerseyman Number 78 Springtime on the Delaware River Rich Thrash, Brass Team Volunteer April 1st is a day that always brings a smile to my face. To me it means another cold winter season is history and that nice warm spring and summer days are just around the corner. In my book any day I can put the top down is a good day… On the ship it means that my fellow brass polishers and I will be able to work outside once again and put a shine on those things you just can’t work on in the winter when the wind whips off the Delaware and forces us below decks seeking a warmer place to do our thing. This past winter we’ve spent a lot of time in the lower levels of Turret 2 polishing all the brass in that area, and believe me it’s a target rich environment for brass polishing down there. I’m so happy the Turret 2 Experience will finally be opening to the public this coming weekend. This is something that has been two years in the making and on which a long list of volunteers and staff have worked many hours to give visitors the most realistic experience possible. The first tour of this area will start at 11:00 am this Sunday; tour groups will be limited to a maximum of 15 guests. The price for this new interactive tour is $29.95. -

Review by Andrew Lambert King’S College, London ______

A Global Forum for Naval Historical Scholarship International Journal of Naval History December 2007 Volume 6 Number 3 Robert J. Cressman, USS Ranger 1934-1946: The Navy’s First Flattop from Keel to Mast, Washington, DC: Potomac Books, 2003. 451 pp., heavily illustrated. Review by Andrew Lambert King’s College, London ______________________________________________________________________ The USS Ranger was a curious ship. Designed to meet the arbitrary tonnage limits of the Washington Treaty limiting naval armaments at a time when the United States Navy had no operational experience of large carriers, she proved to be a very good aviation platform for biplanes and the first generation of monoplane carrier aircraft, but these qualities came at a price. The ship was lightly built, underpowered and lacked worthwhile protection against underwater damage. That said Ranger served her country well, because her crews sustained very high standards, and the Navy had the good sense to keep her out of the Pacific fighting. By concentrating on the human side of the Ranger’s career Robert Cressman provides a remarkable insight into the making of the Air Navy. This is a book about training; hard, dangerous, sustained training. While he follows the ship on her pre-war and wartime deployments the focus is always on the air group. An endless parade of fresh faced young men that stare out from posed shots, all too many of them mark the fact that they died in training accidents. While the stream of deck accidents and landing milestones can occasionally dull the senses they are the key to the story of this ship, and of the Navy’s air arm. -

Catalogos Modelismo Abril 2021.Xlsx

ATLANTIS MODELS301 1/48 US M46 Patton Tank (formerly Aurora) Bs210 ATLANTIS MODELS303 1/48 Russian JS III Stalin Tank (formerly Aurora) Bs210 ATLANTIS MODELS307 1/48 US Army 8-inch Howitzer Gun (formerly Aurora) Bs210 ATLANTIS MODELS1401 1/48 1955 Chevrolet 2-Ton Stake Bed Truck (formerly Revell) Bs210 ATLANTIS MODELS1402 1/48 White-Fruehauf Gas Truck w/2 Figures (formerly Revell) Bs210 AEROBONUS480001 1/48 SPPU22 Soviet Gun Pods (D) Bs140 AEROBONUS480002 1/48 MBD3 Soviet Multiple Bomb Racks (D) Bs170 AEROBONUS480003 1/48 FAB250TS Soviet Bombs (D) Bs120 AEROBONUS480004 1/48 BetAb500 Soviet Penetration Bombs (D) Bs120 AEROBONUS480005 1/48 B13L Soviet Rocket Launchers (D) Bs120 AEROBONUS480006 1/48 B8M Soviet Rocket Launchers (D) Bs120 AEROBONUS480007 1/48 UB16-57 Soviet Rocket Launchers Bs95 AEROBONUS480008 1/48 UB32 Soviet Rocket Launchers (D) Bs120 AEROBONUS480009 1/48 UB16 Soviet Rocket Launchers (D) Bs105 AEROBONUS480010 1/48 Ch25MP (AS12 Kegler) Air-to-Ground Missiles (D) Bs170 AEROBONUS480011 1/48 Ch25MR (AS10 Karen) Air-to-Ground Missiles (D) Bs170 AEROBONUS480012 1/48 Ch25ML (AS10 Karen) Air-to-Ground Missile (D) Bs170 AEROBONUS480013 1/48 Ch25MT (AS10 Karen) Air-to-Ground Missile (D) Bs170 AEROBONUS480014 1/48 IAB500 Imitation Aerial Bomb w/BD3-23N Pylon (D) Bs120 AEROBONUS480015 1/48 Ch31 (AS17 Krypton) Air-to-Surface Missile (D) Bs305 AEROBONUS480016 1/48 R60 (AA8 Aphid) Air-to-Air Missiles (D) Bs120 AEROBONUS480017 1/48 Ch58 (AS11 Kilter) Air-to-Surface Missiles (D) Bs305 AEROBONUS480018 1/48 S25L Air-to-Ground Rocket Bs140 -

Panzers I & II: Germany's Light Tanks (Hitler's War Machine)

This edition published in 2013 by Pen & Sword Military An imprint of Pen & Sword Books Ltd 47 Church Street Barnsley South Yorkshire S70 2AS First published in Great Britain in 2012 in digital format by Coda Books Ltd. Copyright © Coda Books Ltd, 2012 Published under licence by Pen & Sword Books Ltd. ISBN: 978 1 78159 209 0 EPUB ISBN: 978 1 47384 531 2 PRC ISBN: 978 1 47384 539 8 A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing. Printed and bound in India By Replika Press Pvt. Ltd. Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the Imprints of Pen & Sword Aviation, Pen & Sword Family History, Pen & Sword Maritime, Pen & Sword Military, Pen & Sword Discovery, Pen & Sword Politics, Pen & Sword Atlas, Pen & Sword Archaeology, Wharncliffe Local History, Wharncliffe True Crime, Wharncliffe Transport, Pen & Sword Select, Pen & Sword Military Classics, Leo Cooper, The Praetorian Press, Claymore Press, Remember When, Seaforth Publishing and Frontline Publishing For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED 47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk CONTENTS Introduction Section 1: The Panzer I Section 2: The Panzer II Section 3: Legion Condor Section 4: Contemporary Documents More from the Same Series INTRODUCTION HIS BOOK forms part of the series entitled ‘Hitler’s War Machine.’ The aim is to Tprovide the reader with a varied range of materials drawn from original writings covering the strategic, operational and tactical aspects of the weapons and battles of Hitler’s war. -

Four Medals for Norway

(Periodicals postage paid in Seattle, WA) TIME-DATED MATERIAL — DO NOT DELAY Travel Research & Education Brooklyn Norwegians Celebrating visit Vanse’s Ideer er ikke sommerfugler, seven years de er et resultat av hardt arbeid. American Festival – Rudolf Rolfs of Barnehage Read more on page 9 Read more on page 5 Norwegian American Weekly Vol. 123 No. 29 August 17, 2012 Established May 17, 1889 • Formerly Western Viking and Nordisk Tidende $1.50 per copy Norway.com News Find more at www.norway.com Four medals for Norway News Norwegian Finance Minister Norway finishes Sigbjørn Johnsen predicts a tight National Budget for 2013, 2012 Olympic tailored to the financial crisis Games in London in Europe. “The international growth is still weak. This under- with two gold, lines the need for a state budget which is adapted to the com- one silver and petition we face,” the Finance one bronze Minister says. Johnsen says to Dagsavisen that is important a steady course. At the end of August the coalition govern- CHRISTY OLSEN FIELD ment will meet for their annual Managing Editor budget conference to decide on how the budget funds will be distributed among the different At the end of the 2012 Sum- departments for next year. mer Olympics in London, Norway Photos: Handball.no, Face- book and London2012 (blog.norway.com/category/ looked at the two-week competi- tion with golden moments mixed Clockwise from top left: news) The Norwegian women’s with some surprising disappoint- handball team won the Culture ments. Long a dominating country gold medal match. Fencer An increasing number of Nor- in the Winter Olympics, Norway Bartosz Piasecki took sil- wegians choose to travel by air finished in 35th place with four ver, and Alexander Kristoff when moving from one point medals: two gold, one silver and won bronze in road racing, and canoer Eirik Verås to another, according to a sur- See > OLYMPICS, page 6 vey made by the Norwegian Larsen won gold in the 1000m canoe sprint.