Complaints Handling Polict

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Conservation Management Zones of Australia

Conservation Management Zones of Australia Mitchell Grasslands Prepared by the Department of the Environment Acknowledgements This project and its associated products are the result of collaboration between the Department of the Environment’s Biodiversity Conservation Division and the Environmental Resources Information Network (ERIN). Invaluable input, advice and support were provided by staff and leading researchers from across the Department of Environment (DotE), Department of Agriculture (DoA), the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) and the academic community. We would particularly like to thank staff within the Wildlife, Heritage and Marine Division, Parks Australia and the Environment Assessment and Compliance Division of DotE; Nyree Stenekes and Robert Kancans (DoA), Sue McIntyre (CSIRO), Richard Hobbs (University of Western Australia), Michael Hutchinson (ANU); David Lindenmayer and Emma Burns (ANU); and Gilly Llewellyn, Martin Taylor and other staff from the World Wildlife Fund for their generosity and advice. Special thanks to CSIRO researchers Kristen Williams and Simon Ferrier whose modelling of biodiversity patterns underpinned identification of the Conservation Management Zones of Australia. Image Credits Front Cover: Lawn Hill National Park – Peter Lik Page 4: Kowaris (Dasyuroides byrnei) – Leong Lim Page 10: Oriental Pratincole (Glareola maldivarum) – JJ Harrison Page 16: Australian Fossil Mammal Sites (Riversleigh) – World Heritage Listed site – Colin Totterdell Page 18: Mitchell Grasslands -

Loranthaceae1

Flora of South Australia 5th Edition | Edited by Jürgen Kellermann LORANTHACEAE1 P.J. Lang2 & B.A. Barlow3 Aerial hemi-parasitic shrubs on branches of woody plants attached by haustoria; leaves mostly opposite, entire. Inflorescence terminal or lateral; flowers bisexual; calyx reduced to an entire, lobed or toothed limb at the apex of the ovary, without vascular bundles; corolla free or fused, regular or slightly zygomorphic, 4–6-merous, valvate; stamens as many as and opposite the petals, epipetalous, anthers 2- or 4-locular, mostly basifixed, immobile, introrse and continuous with the filament but sometimes dorsifixed and then usually versatile, opening by longitudinal slits; pollen trilobate; ovary inferior, without differentiated locules or ovules. Fruit berry-like; seed single, surrounded by a copious viscous layer. Mistletoes. 73 genera and around 950 species widely distributed in the tropics and south temperate regions with a few species in temperate Asia and Europe. Australia has 12 genera (6 endemic) and 75 species. Reference: Barlow (1966, 1984, 1996), Nickrent et al. (2010), Watson (2011). 1. Petals free 2. Anthers basifixed, immobile, introrse; inflorescence axillary 3. Inflorescence not subtended by enlarged bracts more than 20 mm long ....................................... 1. Amyema 3: Inflorescence subtended by enlarged bracts more than 20 mm long which enclose the buds prior to anthesis ......................................................................................................................... 2. Diplatia 2: Anthers dorsifixed, versatile; inflorescence terminal ........................................................................... 4. Muellerina 1: Petals united into a curved tube, more deeply divided on the concave side ................................................ 3. Lysiana 1. AMYEMA Tiegh. Bull. Soc. Bot. France 41: 499 (1894). (Greek a-, negative; myeo, I instruct, initiate; referring to the genus being not previously recognised; cf. -

DRAFT 25/10/90; Plant List Updated Oct. 1992; Notes Added June 2021

DRAFT 25/10/90; plant list updated Oct. 1992; notes added June 2021. PRELIMINARY REPORT ON THE CONSERVATION VALUES OF OPEN COUNTRY PADDOCK, BOOLARDY STATION Allan H. Burbidge and J.K. Rolfe INTRODUCTION Boolardy Station is situated about 150 km north of Yalgoo and 140 km west-north-west of Cue, in the Shire of Murchison, Western Australia. Open Country Paddock (about 16 000 ha) is in the south-east corner of the station, at 27o05'S, 116o50'E. The most prominent named feature is Coolamooka Hill, near the eastern boundary of the paddock. There are no conservation reserves in this region, although there are some small reserves set aside for various other purposes. Previous biological data for the station consist of broad scale vegetation mapping and land system mapping. Beard (1976) mapped the entire Murchison region at 1: 1 000 000. The Open Country Paddock area was mapped as supporting mulga woodlands and shrublands. More detailed mapping of land system units for rangeland assessment purposes has been carried out more recently at a scale of 1: 40 000 (Payne and Curry in prep.). Seven land systems were identified in open Country Paddock (Fig. 1). Apart from these studies, no detailed biological survey work appears to have been done in the area. Open Country Paddock has been only lightly grazed by domestic stock because of the presence of Kite-leaf Poison (Gastrolobium laytonii) and a lack of fresh water. Because of this and the generally good condition of the paddock and presence of a wide range of plant species, P.J. -

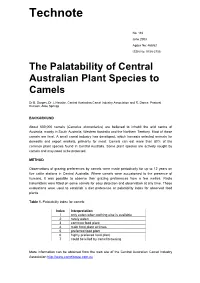

Palatability of Plants to Camels (DBIRD NT)

Technote No. 116 June 2003 Agdex No: 468/62 ISSN No: 0158-2755 The Palatability of Central Australian Plant Species to Camels Dr B. Dorges, Dr J. Heucke, Central Australian Camel Industry Association and R. Dance, Pastoral Division, Alice Springs BACKGROUND About 600,000 camels (Camelus dromedarius) are believed to inhabit the arid centre of Australia, mainly in South Australia, Western Australia and the Northern Territory. Most of these camels are feral. A small camel industry has developed, which harvests selected animals for domestic and export markets, primarily for meat. Camels can eat more than 80% of the common plant species found in Central Australia. Some plant species are actively sought by camels and may need to be protected. METHOD Observations of grazing preferences by camels were made periodically for up to 12 years on five cattle stations in Central Australia. Where camels were accustomed to the presence of humans, it was possible to observe their grazing preferences from a few metres. Radio transmitters were fitted on some camels for easy detection and observation at any time. These evaluations were used to establish a diet preference or palatability index for observed food plants. Table 1. Palatability index for camels Index Interpretation 1 only eaten when nothing else is available 2 rarely eaten 3 common food plant 4 main food plant at times 5 preferred food plant 6 highly preferred food plant 7 could be killed by camel browsing More information can be obtained from the web site of the Central Australian Camel Industry Association http://www.camelsaust.com.au 2 RESULTS Table 2. -

MVG 16 Acacia Shrublands DRAFT

MVG 16 - ACACIA SHRUBLANDS Acacia hillii, Tanami Desert, NT (Photo: D. Keith) Overview The overstorey of MVG 16 is dominated by multi-stemmed acacia shrubs. The most widespread species is Acacia aneura (mulga). Mulga vegetation takes on a variety of structural expressions and is consequently classified partly within MVG 16 where the overstorey is dominated by multi-stemmed shrubs, partly within MVG 6 in accordance with the Kyoto Protocol definition of forest cover in Australia (trees > 2 m tall and crown cover > 20%, foliage projective cover > 10%); and partly within MVG 13 where the woody dominants are predominantly single-stemmed, but with crown cover less than 20%. Occurs where annual rainfall is below 250mm in southern Australia and below 350mm in northern Australia (Hodgkinson 2002; Foulkes et al. 2014). Species composition varies along rainfall gradients, with substrate and rainfall seasonality (Beadle 1981; Johnson and Burrows 1994). Transitions into MVG 13 Acacia woodlands with higher rainfall and varying soil types. Is most commonly found on red earth soils (Hodgkinson 2002). Facts and figures Major Vegetation Group MVG 16 - Acacia Shrublands Major Vegetation Subgroups 20. Stony mulga woodlands and shrublands NSW, (number of NVIS descriptions) NT, QLD, SA, WA 23. Sandplain Acacia woodlands and shrublands NSW, NT, QLD, SA, WA Typical NVIS structural formations Shrubland (tall, mid,) Open shrubland (tall, mid,) Sparse shrubland (tall, mid,) Number of IBRA regions 53 Most extensive in IBRA region Est. pre-1750 and present : Great Victoria Desert (WA and SA) Estimated pre-1750 extent (km2) 865 845 Present extent (km2) 851 274 Area protected (km2) 85 444 Acacia ligulata (sandhill wattle), SA (Photo: M. -

Comparative Biology of Seed Dormancy-Break and Germination in Convolvulaceae (Asterids, Solanales)

University of Kentucky UKnowledge University of Kentucky Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2008 COMPARATIVE BIOLOGY OF SEED DORMANCY-BREAK AND GERMINATION IN CONVOLVULACEAE (ASTERIDS, SOLANALES) Kariyawasam Marthinna Gamage Gehan Jayasuriya University of Kentucky, [email protected] Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Jayasuriya, Kariyawasam Marthinna Gamage Gehan, "COMPARATIVE BIOLOGY OF SEED DORMANCY- BREAK AND GERMINATION IN CONVOLVULACEAE (ASTERIDS, SOLANALES)" (2008). University of Kentucky Doctoral Dissertations. 639. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/gradschool_diss/639 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Kentucky Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION Kariyawasam Marthinna Gamage Gehan Jayasuriya Graduate School University of Kentucky 2008 COMPARATIVE BIOLOGY OF SEED DORMANCY-BREAK AND GERMINATION IN CONVOLVULACEAE (ASTERIDS, SOLANALES) ABSRACT OF DISSERTATION A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the College of Art and Sciences at the University of Kentucky By Kariyawasam Marthinna Gamage Gehan Jayasuriya Lexington, Kentucky Co-Directors: Dr. Jerry M. Baskin, Professor of Biology Dr. Carol C. Baskin, Professor of Biology and of Plant and Soil Sciences Lexington, Kentucky 2008 Copyright © Gehan Jayasuriya 2008 ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION COMPARATIVE BIOLOGY OF SEED DORMANCY-BREAK AND GERMINATION IN CONVOLVULACEAE (ASTERIDS, SOLANALES) The biology of seed dormancy and germination of 46 species representing 11 of the 12 tribes in Convolvulaceae were compared in laboratory (mostly), field and greenhouse experiments. -

Literaturverzeichnis

Literaturverzeichnis Abaimov, A.P., 2010: Geographical Distribution and Ackerly, D.D., 2009: Evolution, origin and age of Genetics of Siberian Larch Species. In Osawa, A., line ages in the Californian and Mediterranean flo- Zyryanova, O.A., Matsuura, Y., Kajimoto, T. & ras. Journal of Biogeography 36, 1221–1233. Wein, R.W. (eds.), Permafrost Ecosystems. Sibe- Acocks, J.P.H., 1988: Veld Types of South Africa. 3rd rian Larch Forests. Ecological Studies 209, 41–58. Edition. Botanical Research Institute, Pretoria, Abbadie, L., Gignoux, J., Le Roux, X. & Lepage, M. 146 pp. (eds.), 2006: Lamto. Structure, Functioning, and Adam, P., 1990: Saltmarsh Ecology. Cambridge Uni- Dynamics of a Savanna Ecosystem. Ecological Stu- versity Press. Cambridge, 461 pp. dies 179, 415 pp. Adam, P., 1994: Australian Rainforests. Oxford Bio- Abbott, R.J. & Brochmann, C., 2003: History and geography Series No. 6 (Oxford University Press), evolution of the arctic flora: in the footsteps of Eric 308 pp. Hultén. Molecular Ecology 12, 299–313. Adam, P., 1994: Saltmarsh and mangrove. In Groves, Abbott, R.J. & Comes, H.P., 2004: Evolution in the R.H. (ed.), Australian Vegetation. 2nd Edition. Arctic: a phylogeographic analysis of the circu- Cambridge University Press, Melbourne, pp. marctic plant Saxifraga oppositifolia (Purple Saxi- 395–435. frage). New Phytologist 161, 211–224. Adame, M.F., Neil, D., Wright, S.F. & Lovelock, C.E., Abbott, R.J., Chapman, H.M., Crawford, R.M.M. & 2010: Sedimentation within and among mangrove Forbes, D.G., 1995: Molecular diversity and deri- forests along a gradient of geomorphological set- vations of populations of Silene acaulis and Saxi- tings. -

Bardi Plants an Annotated List of Plants and Their Use

H.,c H'cst. /lust JIus lH8f), 12 (:J): :317-:359 BanE Plants: An Annotated List of Plants and Their Use by the Bardi Aborigines of Dampierland, in North-western Australia \!o\a Smith and .\rpad C. Kalotast Abstract This paper presents a descriptive list of the plants identified and used by the BarcE .\borigines of the Dampierland Peninsula, north~\q:stern Australia. It is not exhaust~ ive. The information is presented in two wavs. First is an alphabetical list of Bardi names including genera and species, use, collection number and references. Second is a list arranged alphabetically according to botanical genera and species, and including family and Bardi name. Previous ethnographic research in the region, vegetation communities and aspects of seasonality (I) and taxonomy arc des~ cribed in the Introduction. Introduction At the time of European colonisation of the south~west Kimberley in the mid nineteenth century, the Bardi Aborigines occupied the northern tip of the Dam pierland Peninsula. To their east lived the island-dwelling Djawi and to the south, the ~yulnyul. Traditionally, Bardi land ownership was based on identification with a particular named huru, translated as home, earth, ground or country. Forty-six bum have been identified (Robinson 1979: 189), and individually they were owned by members of a family tracing their ownership patrilineally, and known by the bum name. Collectively, the buru fall into four regions with names which are roughly equivalent to directions: South: Olonggong; North-west: Culargon; ~orth: Adiol and East: Baniol (Figure 1). These four directional terms bear a superficial resemblance to mainland subsection kinship patterns, in that people sometimes refer to themselves according to the direction in which their land lies, and indeed 'there are. -

Brockman 4 Camps Vegetation and Flora Survey

Biota (n): The living creatures of an area; the flora and fauna together 21 August 2012 Peter Royce Principal Advisor - Environmental Approvals Approvals Division Rio Tinto Central Park 152-158 St George’s Terrace Perth WA 6000 (via email) Dear Peter Brockman 4 Camps Vegetation and Flora Survey Biota Environmental Sciences (Biota) was commissioned by Rio Tinto Pty Ltd (Rio Tinto) to conduct a vegetation and flora survey for the Brockman Camps area (hereafter referred to as the “study area”), located east of the operational BS4 mine and immediately adjacent to the existing accommodation village. This brief report presents the results obtained during that field work. Scope and Objectives The potential development site (defined by the boundaries of the study area) around the Brockman Camps extends over an area of 180 ha, of which 53 ha has been cleared or is deemed as extensively disturbed. Prior to this clearing, a survey conducted by Biota in early December 2006 and late January 2007 recorded no flora of conservation significance in this area (Biota 2007). Vegetation over about 30 ha of the remaining area was previously mapped as part of the Brockman Syncline 4 (BS4) project (Biota 2006). The botanical field survey was therefore conducted over the remaining 97 ha of the study area (adjoining the previously surveyed BS4 study area). This survey was undertaken in accordance with the Guidance Statement No. 51 "Terrestrial Flora and Vegetation Surveys for Environmental Impact Assessment in Western Australia" (EPA 2004). The scope and objectives -

Images from the Outback

Images from the Outback Item Type Article Authors Johnson, Matthew B. Publisher University of Arizona (Tucson, AZ) Journal Desert Plants Rights Copyright © Arizona Board of Regents. The University of Arizona. Download date 26/09/2021 00:25:31 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/555917 Outback Johnson 21 species of Acacia are found in Australia (Orchard and Images from the Outback - Wilson, 200 I ), though only a relatively small percentage of Notes on Plants of the Australian these occur in desert habitats. Acacia woodlands can be dense or open, and are sometimes mixed with grasses including Dry Zone spinifex. Spinifex grasslands, dominated by species of Plectraclme and Triodia (p. 27) are widespread on sandy plains as well as rocky slopes and sand dunes. These grasses, Matthew B. Johnson many with stiff, rolled leaves that end in a sharp point, form Desert Legume Program clumps or tussocks. Fires are frequent in some spinifex The University of Arizona communities and the woody plants that grow there are 2120 East Allen Road necessarily fire-adapted. Chenopod shrublands are low stature communities composed of numerous shrubs and Tucson, AZ 85719 herbaceous plants in the Chenopodiaceae. Less widespread [email protected] than acacia woodland and spinifex grassland, this type of Yegetation is found mostly in the southern parts ofAustralia's A visit to the Sydney area of Australia in 1987 tirst sparked arid zone (Van Oosterzee, 1991 ). Beyond the deserts lie my interest in seeing more of the Island Continent and in semi-arid woodlands dominated by species of Euca~vptus particular, the extensive dry regions of the country. -

The Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research (ACIAR) Was Established in June 1982 by an Act of the Australian Parliament

The Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research (ACIAR) was established in June 1982 by an Act of the Australian Parliament. Its mandate is to help identify agricultural problems in developing countries and to commission collaborative research between Australian and developing country researchers in fields where Australia has a special research competence. Where trade names are used this does not constitute endorsement of nor discrimination against any product by the Centre. ACIAR PROCEEDINGS This series of publications includes the full proceedings of research workshops or symposia organised or supported by ACIAR. Numbers in this series are distrib uted internationally to selected individuals and scientific institutions. Previous numbers in the series are listed on the inside back cover. © Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research G.P.O. Box 1571, Canberra, A.C.T. 2601 Turnbull, John W. 1987. Australian acacias in developing countries: proceedings of an international workshop held at the Forestry Training Centre, Gympie, Qld., Australia, 4-7 August 1986. ACIAR Proceedings No. 16, 196 p. ISBN 0 949511 269 Typeset and laid out by Union Offset Co. Pty Ltd, Fyshwick, A.C.T. Printed by Brown Prior Anderson Pty Ltd, 5 Evans Street Burwood Victoria 3125 Australian Acacias in Developing Countries Proceedings of an international workshop held at the Forestry Training Centre, Gympie, Qld., Australia, 4-7 August 1986 Editor: John W. Turnbull Workshop Steering Committee: Douglas 1. Boland, CSIRO Division of Forest Research Alan G. Brown, CSIRO Division of Forest Research John W. Turnbull, ACIAR and NFTA Paul Ryan, Queensland Department of Forestry Cosponsors: Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research (ACIAR) Nitrogen Fixing Tree Association (NFTA) CSIRO Division of Forest Research Queensland Department of Forestry Contents Foreword J . -

A Broad Typology of Dry Rainforests on the Western Slopes of New South Wales

A broad typology of dry rainforests on the western slopes of New South Wales Timothy J. Curran1,2, Peter J. Clarke1, and Jeremy J. Bruhl 1 1 Botany, Centre for Ecology, Evolution and Systematics, University of New England, Armidale NSW 2351, AUSTRALIA. 2 Author for correspondence. Current address: The School for Field Studies, Centre for Rainforest Studies, PO Box 141, Yungaburra, Queensland 4884, AUSTRALIA. [email protected] & [email protected] Abstract: Dry rainforests are those communities that have floristic and structural affinities to mesic rainforests and occur in parts of eastern and northern Australia where rainfall is comparatively low and often highly seasonal. The dry rainforests of the western slopes of New South Wales are poorly-understood compared to other dry rainforests in Australia, due to a lack of regional scale studies. This paper attempts to redress this by deriving a broad floristic and structural typology for this vegetation type. Phytogeographical analysis followed full floristic surveys conducted on 400 m2 plots located within dry rainforest across the western slopes of NSW. Cluster analysis and ordination of 208 plots identified six floristic groups. Unlike in some other regional studies of dry rainforest these groups were readily assigned to Webb structural types, based on leaf size classes, leaf retention classes and canopy height. Five community types were described using both floristic and structural data: 1)Ficus rubiginosa–Notelaea microcarpa notophyll vine thicket, 2) Ficus rubiginosa–Alectryon subcinereus–Notelaea microcarpa notophyll vine forest, 3) Elaeodendron australe–Notelaea microcarpa–Geijera parviflora notophyll vine thicket, 4) Notelaea microcarpa– Geijera parviflora–Ehretia membranifolia semi-evergreen vine thicket, and 5) Cadellia pentastylis low microphyll vine forest.