MVG 16 Acacia Shrublands DRAFT

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Supplementary Materialsupplementary Material

10.1071/BT13149_AC © CSIRO 2013 Australian Journal of Botany 2013, 61(6), 436–445 SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL Comparative dating of Acacia: combining fossils and multiple phylogenies to infer ages of clades with poor fossil records Joseph T. MillerA,E, Daniel J. MurphyB, Simon Y. W. HoC, David J. CantrillB and David SeiglerD ACentre for Australian National Biodiversity Research, CSIRO Plant Industry, GPO Box 1600 Canberra, ACT 2601, Australia. BRoyal Botanic Gardens Melbourne, Birdwood Avenue, South Yarra, Vic. 3141, Australia. CSchool of Biological Sciences, Edgeworth David Building, University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW 2006, Australia. DDepartment of Plant Biology, University of Illinois, Urbana, IL 61801, USA. ECorresponding author. Email: [email protected] Table S1 Materials used in the study Taxon Dataset Genbank Acacia abbreviata Maslin 2 3 JF420287 JF420065 JF420395 KC421289 KC796176 JF420499 Acacia adoxa Pedley 2 3 JF420044 AF523076 AF195716 AF195684; AF195703 Acacia ampliceps Maslin 1 KC421930 EU439994 EU811845 Acacia anceps DC. 2 3 JF420244 JF420350 JF419919 JF420130 JF420456 Acacia aneura F.Muell. ex Benth 2 3 JF420259 JF420036 JF420366 JF419935 JF420146 KF048140 Acacia aneura F.Muell. ex Benth. 1 2 3 JF420293 JF420402 KC421323 JQ248740 JF420505 Acacia baeuerlenii Maiden & R.T.Baker 2 3 JF420229 JQ248866 JF420336 JF419909 JF420115 JF420448 Acacia beckleri Tindale 2 3 JF420260 JF420037 JF420367 JF419936 JF420147 JF420473 Acacia cochlearis (Labill.) H.L.Wendl. 2 3 KC283897 KC200719 JQ943314 AF523156 KC284140 KC957934 Acacia cognata Domin 2 3 JF420246 JF420022 JF420352 JF419921 JF420132 JF420458 Acacia cultriformis A.Cunn. ex G.Don 2 3 JF420278 JF420056 JF420387 KC421263 KC796172 JF420494 Acacia cupularis Domin 2 3 JF420247 JF420023 JF420353 JF419922 JF420133 JF420459 Acacia dealbata Link 2 3 JF420269 JF420378 KC421251 KC955787 JF420485 Acacia dealbata Link 2 3 KC283375 KC200761 JQ942686 KC421315 KC284195 Acacia deanei (R.T.Baker) M.B.Welch, Coombs 2 3 JF420294 JF420403 KC421329 KC955795 & McGlynn JF420506 Acacia dempsteri F.Muell. -

Loranthaceae1

Flora of South Australia 5th Edition | Edited by Jürgen Kellermann LORANTHACEAE1 P.J. Lang2 & B.A. Barlow3 Aerial hemi-parasitic shrubs on branches of woody plants attached by haustoria; leaves mostly opposite, entire. Inflorescence terminal or lateral; flowers bisexual; calyx reduced to an entire, lobed or toothed limb at the apex of the ovary, without vascular bundles; corolla free or fused, regular or slightly zygomorphic, 4–6-merous, valvate; stamens as many as and opposite the petals, epipetalous, anthers 2- or 4-locular, mostly basifixed, immobile, introrse and continuous with the filament but sometimes dorsifixed and then usually versatile, opening by longitudinal slits; pollen trilobate; ovary inferior, without differentiated locules or ovules. Fruit berry-like; seed single, surrounded by a copious viscous layer. Mistletoes. 73 genera and around 950 species widely distributed in the tropics and south temperate regions with a few species in temperate Asia and Europe. Australia has 12 genera (6 endemic) and 75 species. Reference: Barlow (1966, 1984, 1996), Nickrent et al. (2010), Watson (2011). 1. Petals free 2. Anthers basifixed, immobile, introrse; inflorescence axillary 3. Inflorescence not subtended by enlarged bracts more than 20 mm long ....................................... 1. Amyema 3: Inflorescence subtended by enlarged bracts more than 20 mm long which enclose the buds prior to anthesis ......................................................................................................................... 2. Diplatia 2: Anthers dorsifixed, versatile; inflorescence terminal ........................................................................... 4. Muellerina 1: Petals united into a curved tube, more deeply divided on the concave side ................................................ 3. Lysiana 1. AMYEMA Tiegh. Bull. Soc. Bot. France 41: 499 (1894). (Greek a-, negative; myeo, I instruct, initiate; referring to the genus being not previously recognised; cf. -

Arid and Semi-Arid Lakes

WETLAND MANAGEMENT PROFILE ARID AND SEMI-ARID LAKES Arid and semi-arid lakes are key inland This profi le covers the habitat types of ecosystems, forming part of an important wetlands termed arid and semi-arid network of feeding and breeding habitats for fl oodplain lakes, arid and semi-arid non- migratory and non-migratory waterbirds. The fl oodplain lakes, arid and semi-arid lakes support a range of other species, some permanent lakes, and arid and semi-arid of which are specifi cally adapted to survive in saline lakes. variable fresh to saline water regimes and This typology, developed by the Queensland through times when the lakes dry out. Arid Wetlands Program, also forms the basis for a set and semi-arid lakes typically have highly of conceptual models that are linked to variable annual surface water infl ows and vary dynamic wetlands mapping, both of which can in size, depth, salinity and turbidity as they be accessed through the WetlandInfo website cycle through periods of wet and dry. The <www.derm/qld.gov.au/wetlandinfo>. main management issues affecting arid and semi-arid lakes are: water regulation or Description extraction affecting local and/or regional This wetland management profi le focuses on the arid hydrology, grazing pressure from domestic and semi-arid zone lakes found within Queensland’s and feral animals, weeds and tourism impacts. inland-draining catchments in the Channel Country, Desert Uplands, Einasleigh Uplands and Mulga Lands bioregions. There are two broad types of river catchments in Australia: exhoreic, where most rainwater eventually drains to the sea; and endorheic, with internal drainage, where surface run-off never reaches the sea but replenishes inland wetland systems. -

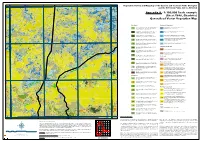

Appendix 9 - 1:100,000 Scale Example (Sheet 5648, Charlotte) Generalised Vector Vegetation Map

133°30'E 133°40'E 133°50'E 134°E 24°30'S Vegetation Survey and Mapping of the Eastern and Southern Finke Bioregion 24°30'S and the NT Stony Plains Inliers, NT & SA Appendix 9 - 1:100,000 Scale example (Sheet 5648, Charlotte) Generalised Vector Vegetation Map Woodland Chenopod Shrubland Acacia aneura ( Mulga) Low Open Woodland TO Tall Open Shrubland of Atriplex nummularia (Old man saltbush) Low Sparse Chenopod 1 Acacia estrophiolata (Ironwood) on clay loam plains and red earth 4 shrubland over Low Sparse Tussock grasses. soils+/- Atriplex vesicaria and Eragrostis eriopoda . Acacia georginae / Acacia cambagei ( Gidgee) Low Woodland to Tall Atriplex vesicaria (Pop saltbush) Low Open Chenopod Shrubland.+/- 2 Shrubland.+/- Eucalyptus coolabah subsp. Arida , Codonocarpus 5 Maireana astrotricha over tussock grasses. cotinifolius , Eulalia aurea, Eriachne ovata and Atriplex vesicaria . Eucalyptus coolabah subsp. arida (Coolabah) Woodland. +/- Maireana aphylla (Cottonbush) Low Sparse Chenopod Shrubland. +/- 12 Muehlenbeckia florulenta , Acacia aneura , Senna artemisioides ssp. 8 Fimbristylis dichotoma , Dactyloctenium radulans and Eragrostis dielsii. Filifolia , Marsilea sp ., Cynodon dactylon , and Cenchrus ciliaris . Maireana astrotricha (Low bluebush) Low Sparse Chenopod Shrubland Eucalyptus camaldulensis var. obtusa (River red gum) Woodland.+/- TO Sparse shrubland of Senna artemisioides n. coriacea and 13 Eucalyptus coolabah subsp. arida , Cynodon dactylon , Eulalia aurea and 9 Eremophila duttonii (Harlequin fuchsia bush). Cyperus gymnocaulos . 24°40'S Hakea leucoptera subsp. leucoptera (Needlewood) Open Woodland. +- Sclerolaena (mixed) Low Sparse Chenopod Shrubland.+/- Enneapogon 24°40'S 14 Eremophila sturtii , Senna artemisioides ssp. filifolia , Hakea leucoptera 15 avenaceus Aristida contorta , Sporobolus actinocladus . subsp. leucoptera and Triodia basedowii . Acacia calcicola (Northern Myall) Sparse Woodland +/- Eremophila Samphire Shrubland 23 duttonii , Acacia calcicola , Atriplex vesicaria , Maireana georgei and mixed short grasses. -

Assessment of Dalwallinu Shire Wattles Considered Prospective for Human Food

Assessment of Dalwallinu Shire Wattles considered prospective for human food A Report Produced For The Shire of Dalwallinu By Bruce Maslin and Jordan Reid December 2008 1 2 Assessment of Dalwallinu Shire Wattles considered prospective for human food By Bruce Maslin & Jordan Reid Western Australian Herbarium, Department of Environment and Conservation, Kensington, W.A. Preamble Following a request from Mr Robert Nixon, President of the Dalwallinu Shire Council, and a meeting with Shire Councillors McFarlane, Carter, Dinnie and Sanderson, CEO Crispin and Brent Parkinson, we undertook a quick assessment of the Acacia flora of the Dalwallinu Shire with a view to identifying those species that might have potential for cultivation as a source of commercial quantities of seed for human consumption. The work was conducted between 2-5 December 2008. Introduction There are about 80 different Acacia (Wattle) species that occur in the Shire of Dalwallinu. Ten of these species were included in Edible Wattle Seeds of Southern Australia (Maslin et al. 1998) as having some potential for development as new crop plants as a source of seed for human consumption. From the outset it is recommended that readers familiarize themselves with Maslin et al. (1998) and Simpson & Chudleigh (2001) because these two works provide much valuable information relevant to the domestication of Acacia as human food crop in low rainfall areas. Little or no attempt has been made here to reproduce the information contained in these works (we have simply focused on identifying those species in the Dalwallinu Shire that we consider as prospective for development as new seed crops). -

DRAFT 25/10/90; Plant List Updated Oct. 1992; Notes Added June 2021

DRAFT 25/10/90; plant list updated Oct. 1992; notes added June 2021. PRELIMINARY REPORT ON THE CONSERVATION VALUES OF OPEN COUNTRY PADDOCK, BOOLARDY STATION Allan H. Burbidge and J.K. Rolfe INTRODUCTION Boolardy Station is situated about 150 km north of Yalgoo and 140 km west-north-west of Cue, in the Shire of Murchison, Western Australia. Open Country Paddock (about 16 000 ha) is in the south-east corner of the station, at 27o05'S, 116o50'E. The most prominent named feature is Coolamooka Hill, near the eastern boundary of the paddock. There are no conservation reserves in this region, although there are some small reserves set aside for various other purposes. Previous biological data for the station consist of broad scale vegetation mapping and land system mapping. Beard (1976) mapped the entire Murchison region at 1: 1 000 000. The Open Country Paddock area was mapped as supporting mulga woodlands and shrublands. More detailed mapping of land system units for rangeland assessment purposes has been carried out more recently at a scale of 1: 40 000 (Payne and Curry in prep.). Seven land systems were identified in open Country Paddock (Fig. 1). Apart from these studies, no detailed biological survey work appears to have been done in the area. Open Country Paddock has been only lightly grazed by domestic stock because of the presence of Kite-leaf Poison (Gastrolobium laytonii) and a lack of fresh water. Because of this and the generally good condition of the paddock and presence of a wide range of plant species, P.J. -

Volume 5 Pt 3

Conservation Science W. Aust. 7 (1) : 153–178 (2008) Flora and Vegetation of the banded iron formations of the Yilgarn Craton: the Weld Range ADRIENNE S MARKEY AND STEVEN J DILLON Science Division, Department of Environment and Conservation, Wildlife Research Centre, PO Box 51, Wanneroo WA 6946. Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT A survey of the flora and floristic communities of the Weld Range, in the Murchison region of Western Australia, was undertaken using classification and ordination analysis of quadrat data. A total of 239 taxa (species, subspecies and varieties) and five hybrids of vascular plants were collected and identified from within the survey area. Of these, 229 taxa were native and 10 species were introduced. Eight priority species were located in this survey, six of these being new records for the Weld Range. Although no species endemic to the Weld Range were located in this survey, new populations of three priority listed taxa were identified which represent significant range extensions for these taxa of conservation significance. Eight floristic community types (six types, two of these subdivided into two subtypes each) were identified and described for the Weld Range, with the primary division in the classification separating a dolerite-associated floristic community from those on banded iron formation. Floristic communities occurring on BIF were found to be associated with topographic relief, underlying geology and soil chemistry. There did not appear to be any restricted communities within the landform, but some communities may be geographically restricted to the Weld Range. Because these communities on the Weld Range are so closely associated with topography and substrate, they are vulnerable to impact from mineral exploration and open cast mining. -

Complaints Handling Polict

Agnote No: E46 December 2005 Some Important Forage Plants of the Alice Springs District C. Allan, Pastoral Production, Alice Springs The Alice Springs district extends from the South Australian border north to Tennant Creek and east-west from the Queensland border to the Western Australian border. The area occupied by pastoral properties covers some 300,000 km2. This Agnote describes some of the important forage plants in this region. An associated Agnote "Rangeland Pastures of the Alice Springs District" (G4) describes the major plant communities of the region. Plants growing in the Alice Springs district can be considered in three broad categories: • Woody plants (trees and shrubs). These species browsed by cattle are called topfeed. • Grasses (both annual and perennial species). • Herbage (also called forbs). TREES AND SHRUBS Specific information on the description/recognition, nutritive value and grazing management of topfeeds can be found in the booklet "Fodder Trees and Shrubs of the Northern Territory" (copies available from Technical Publications, Department of Primary Industry, Fisheries and Mines). Some of the important trees and shrubs are: Mulga (Acacia aneura) - useful topfeed on better soil types. Easily killed by fire. Hot fires followed by wet years promote re-establishment. Also increases in wet years in the absence of fire. Witchetty bush (Acacia kempeana) - useful topfeed. Re-sprouts after burning. Can increase in wet years on country north of Alice Springs. Rabbits have impacted on its regeneration on much of the calcareous country south of Alice Springs. Ironwood (Acacia estrophiolata) (not to be confused with the poisonous type in the Top End) useful topfeed when accessible to cattle. -

By H.D.V. PRENDERGAST a Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the Australian National University. January 1

STRUCTURAL, BIOCHEMICAL AND GEOGRAPHICAL RELATIONSHIPS IN AUSTRALIAN c4 GRASSES (POACEAE) • by H.D.V. PRENDERGAST A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the Australian National University. January 1987. Canberra, Australia. i STATEMENT This thesis describes my own work which included collaboration with Dr N .. E. Stone (Taxonomy Unit, R .. S .. B.S .. ), whose expertise in enzyme assays enabled me to obtain comparative information on enzyme activities reported in Chapters 3, 5 and 7; and with Mr M.. Lazarides (Australian National Herbarium, c .. s .. r .. R .. O .. ), whose as yet unpublished taxonomic views on Eragrostis form the basis of some of the discussion in Chapter 3. ii This thesis describes the results of research work carried out in the Taxonomy Unit, Research School of Biological Sciences, The Australian National University during the tenure of an A.N.U. Postgraduate Scholarship. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My time in the Taxonomy Unit has been a happy one: I could not have asked for better supervision for my project or for a more congenial atmosphere in which to work. To Dr. Paul Hattersley, for his help, advice, encouragement and friendship, I owe a lot more than can be said in just a few words: but, Paul, thanks very much! To Mr. Les Watson I owe as much for his own support and guidance, and for many discussions on things often psittacaceous as well as graminaceous! Dr. Nancy Stone was a kind teacher in many days of enzyme assays and Chris Frylink a great help and friend both in and out of the lab •• Further thanks go to Mike Lazarides (Australian National Herbarium, c.s.I.R.O.) for identifying many grass specimens and for unpublished data on infrageneric groups in Eragrostis; Dr. -

Koala Conservation Status in New South Wales Biolink Koala Conservation Review

koala conservation status in new south wales Biolink koala conservation review Table of Contents 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................... 3 2. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................ 6 3. DESCRIPTION OF THE NSW POPULATION .............................................................. 6 Current distribution ............................................................................................................... 6 Size of NSW koala population .............................................................................................. 8 4. INFORMING CHANGES TO POPULATION ESTIMATES ....................................... 12 Bionet Records and Published Reports ............................................................................... 15 Methods – Bionet records ............................................................................................... 15 Methods – available reports ............................................................................................ 15 Results ............................................................................................................................ 16 The 2019 Fires .................................................................................................................... 22 Methods ......................................................................................................................... -

Acacia Study Group Newsletter

Australian Native Plants Society (Australia) Inc. ACACIA STUDY GROUP NEWSLETTER Group Leader and Seed Bank Curator Newsletter Editor and Membership Officer Esther Brueggemeier Bill Aitchison 28 Staton Cr, Westlake, Vic 3337 13 Conos Court, Donvale, Vic 3111 Phone 0411 148874 Phone (03) 98723583 Email: [email protected] No. 110 September 2010 ISSN 1035-4638 Contents Page From The Leader Dear Members, From the Leader 1 What a dramatic start to spring we have had down south. Welcome 2 The locals here are wondering if we are ever to see a dry From Members and Readers 2 day again. Melbourne recently braved some of the strongest Origin of Acacias in Australia 2 and most damaging winds in years with gusts up to 100 Acacia scirpifolia 2 km/h and 130 km/h on the Alps while bringing torrential Acacia glaucoptera 3 downpours to much of the state. Despite being one of the Acacia with part red flowers 3 wettest September's this century, I was amazed to see the Banish the winter blues 3 abundance of wattles bursting into full bloom, as if to say, Acacias and Allergies 4 it’s now or never! Those wattles that flower early, flowered Wattle as a symbol of safety 4 in September. Those wattles that flower late, flowered in Insects and Acacias 5 September, turning my entire garden into a glorious blaze of The Germination of Acacia Seeds 6 golden yellow. Myrtle Rust Fungus 9 Books 9 The Australian Plants issue on Acacias is well and truly Correction 10 printed, though I’m sorry to say, has taken a little longer Seed Bank 10 than expected. -

Vol 21, No 4, October

THE LINNEAN N e wsletter and Pr oceedings of THE LINNEAN SOCIETY OF LONDON Bur lington House , Piccadill y, London W1J 0BF VOLUME 21 • NUMBER 4 • OCTOBER 2005 THE LINNEAN SOCIETY OF LONDON Burlington House, Piccadilly, London W1J 0BF Tel. (+44) (0)20 7434 4479; Fax: (+44) (0)20 7287 9364 e-mail: [email protected]; internet: www.linnean.org President Secretaries Council Professor Gordon McG Reid BOTANICAL The Officers and Dr John R Edmondson Dr Louise Allcock President-elect Prof John R Barnett Professor David F Cutler ZOOLOGICAL Prof Janet Browne Dr Vaughan R Southgate Dr J Sara Churchfield Vice-Presidents Dr John C David Professor Richard M Bateman EDITORIAL Prof Peter S Davis Dr Jenny M Edmonds Professor David F Cutler Mr Aljos Farjon Dr Vaughan R Southgate Dr Michael F Fay COLLECTIONS Dr D J Nicholas Hind Treasurer Mrs Susan Gove Dr Sandra D Knapp Professor Gren Ll Lucas OBE Dr D Tim J Littlewood Dr Keith N Maybury Executive Secretary Librarian & Archivist Dr Brian R Rosen Mr Adrian Thomas OBE Miss Gina Douglas Dr Roger A Sweeting Office/Facilities Manager Deputy Librarian Mr Dominic Clark Mrs Lynda Brooks Finance Library Assistant Conservator Mr Priya Nithianandan Mr Matthew Derrick Ms Janet Ashdown THE LINNEAN Newsletter and Proceedings of the Linnean Society of London Edited by B G Gardiner Editorial .................................................................................................................... 1 Society News ...........................................................................................................