Miocene Stratigraphy and Paleoenvironments of the Calvert Cliffs, Maryland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DGS OFR46.Qxd

State of Delaware DELAWARE GEOLOGICAL SURVEY John H. Talley, State Geologist REPORT OF INVESTIGATIONS NO. 75 STRATIGRAPHY AND CORRELATION OF THE OLIGOCENE TO PLEISTOCENE SECTION AT BETHANY BEACH, DELAWARE by Peter P. McLaughlin1, Kenneth G. Miller2, James V. Browning2, Kelvin W. Ramsey1 Richard N. Benson1, Jaime L. Tomlinson1, and Peter J. Sugarman3 University of Delaware Newark, Delaware 1 Delaware Geological Survey 2008 2 Rutgers University 3 New Jersey Geological Survey State of Delaware DELAWARE GEOLOGICAL SURVEY John H. Talley, State Geologist REPORT OF INVESTIGATIONS NO. 75 STRATIGRAPHY AND CORRELATION OF THE OLIGIOCENE TO PLEISTOCENE SECTION AT BETHANY BEACH, DELAWARE by Peter P. McLaughlin1, Kenneth G. Miller2, James V. Browning2, Kelvin W. Ramsey1, Richard N. Benson,1 Jaime L. Tomlinson,1 and Peter J. Sugarman3 University of Delaware Newark, Delaware 2008 1Delaware Geological Survey 2Rutgers University 3New Jersey Geological Survey Use of trade, product, or firm names in this report is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the Delaware Geological Survey. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ABSTRACTG........................................................................................................................... 1 INTRODUCTIONG................................................................................................................... 1 Previous WorkG.......................................................................................................... 2 AcknowledgmentsG..................................................................................................... -

Smithsonian Contributions to Paleobiology • Number 90

SMITHSONIAN CONTRIBUTIONS TO PALEOBIOLOGY • NUMBER 90 Geology and Paleontology of the Lee Creek Mine, North Carolina, III Clayton E. Ray and David J. Bohaska EDITORS ISSUED MAY 112001 SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION Smithsonian Institution Press Washington, D.C. 2001 ABSTRACT Ray, Clayton E., and David J. Bohaska, editors. Geology and Paleontology of the Lee Creek Mine, North Carolina, III. Smithsonian Contributions to Paleobiology, number 90, 365 pages, 127 figures, 45 plates, 32 tables, 2001.—This volume on the geology and paleontology of the Lee Creek Mine is the third of four to be dedicated to the late Remington Kellogg. It includes a prodromus and six papers on nonmammalian vertebrate paleontology. The prodromus con tinues the historical theme of the introductions to volumes I and II, reviewing and resuscitat ing additional early reports of Atlantic Coastal Plain fossils. Harry L. Fierstine identifies five species of the billfish family Istiophoridae from some 500 bones collected in the Yorktown Formation. These include the only record of Makairapurdyi Fierstine, the first fossil record of the genus Tetrapturus, specifically T. albidus Poey, the second fossil record of Istiophorus platypterus (Shaw and Nodder) and Makaira indica (Cuvier), and the first fossil record of/. platypterus, M. indica, M. nigricans Lacepede, and T. albidus from fossil deposits bordering the Atlantic Ocean. Robert W. Purdy and five coauthors identify 104 taxa from 52 families of cartilaginous and bony fishes from the Pungo River and Yorktown formations. The 10 teleosts and 44 selachians from the Pungo River Formation indicate correlation with the Burdigalian and Langhian stages. The 37 cartilaginous and 40 bony fishes, mostly from the Sunken Meadow member of the Yorktown Formation, are compatible with assignment to the early Pliocene planktonic foraminiferal zones N18 or N19. -

Università Di Pisa

UNIVERSITÀ DI PISA Dottorato di ricerca in scienze della terra XIX Ciclo DISSERTAZIONE FINALE ANALISI SISTEMATICA, PALEOECOLOGICA E PALEOBIOGEOGRAFICA DELLA SELACIOFAUNA PLIO-PLEISTOCENICA DEL MEDITERRANEO Candidato Presidente della Scuola di Dottorato Stefano MARSILI Prof. Paolo Roberto FEDERICI Tutore Prof. Walter LANDINI Dipartimento di scienze della terra 2006 Indice INDICE ABSTRACT CAPITOLO 1 – INTRODUZIONE 1.1. Premessa. 1 1.2. Il Mediterraneo e l’attuale diversità del popolamento a squali. 4 CAPITOLO 2 – MATERIALI E METODI 7 CAPITOLO 3 – INQUADRAMENTO GEOLGICO E STRATIGRAFICO 3.1. Premessa. 15 3.2. Inquadramento geologico e stratigrafico delle sezioni campionate. 16 3.2.1. Le sezioni plioceniche della Romagna. 16 3.2.1.1. Sezione Rio Merli. 17 3.2.1.2. Sezione Rio dei Ronchi. 17 3.2.1.3. Sezione Rio Co di Sasso. 18 3.2.1.4. Sezione Rio Cugno. 19 3.2.2. Le sezioni pleistoceniche dell’Italia Meridionale. 19 3.2.2.1. La sezione di Fiumefreddo. 20 3.2.2.2. La sezione di Grammichele. 22 3.2.2.3. La sezione di Vallone Catrica. 23 3.2.2.4. La sezione di Archi. 23 3.3. Inquadramento geologico e stratigrafico dei bacini centrali del Tora-Fine, di Volterra e di Siena: premessa. 24 3.3.1. Bacino del Tora-Fine. 26 3.3.2. Bacino di Siena-Radicofani. 27 3.3.3. Bacino di Volterra. 29 3.4. Inquadramento geologico e stratigrafico delle principali località storiche. 30 3.4.1. Emilia Romagna. 30 3.4.2. Piemonte. 32 3.4.3. Liguria. 32 3.4.4. Basilicata. -

Description of the Choptane Quadrangle

DESCRIPTION OF THE CHOPTANE QUADRANGLE. By Benjamin Leroy Miller. INTRODUCTION. ment of water power, are located such important towns and dip. The oldest strata dip 50 to 60 feet to the mile in some cities as Trenton, Philadelphia, Wilmington, Baltimore, Wash places, but the succeeding beds are progressively less steeply LOCATION AND AREA. ington, Fredericksburg, Richmond, Petersburg, Raleigh, Cam- inclined and in the youngest deposits a dip of more than a few The Choptank quadrangle lies between parallels 38° 30' and den, Columbia, Augusta, Macon, and Columbus. A line drawn feet to the mile is uncommon. 39° north latitude and meridians 76° and 76° 30' west through these places would approximately separate the Coastal longitude. It includes one-fourth of a square degree of the Plain from the Piedmont Plateau. TOPOGRAPHY. earth's surface and contains 931.51 square miles. From north The Coastal Plain is divided by the present shore line into RELIEF. to south it measures 34.5 miles and from east to west its mean two parts a submerged portion, known as the continental INTRODUCTION. width is 27 miles, as it is 27.1 miles wide along the southern shelf or continental platform, and a,n emerged portion, com and 26.9 miles along the northern border. monly called the Coastal Plain. In some places the line sepa The altitude of the land in the Choptank quadrangle ranges rating the two parts is marked by a sea cliff of moderate from sea level to 120 feet above. The highest point lies about 77 height, but commonly they grade into each other with scarcely 2 miles south of Annapolis on the western margin of the quad perceptible change and the only mark of separation is the shore rangle. -

T Mare Imdurl with Eitkrtlx CMM Ortlx Fossil Club?

• News from the CMM Paleontology Department • Paleo Training at the Smithsonian --... Spring Field Trips (including Lee Creek) • Article· Fossil Shark Teeth on Postage Stamps • Minutes of December meeting The Newsletter of Calvert Marine Museum Fossil Club Volume 17 • Numl:er 1 Febmary 2001 W1n'P Nurnkr 54 UIhtt areyou wing tn do tn g::t mare imdurl with eitkrtlx CMM ortlx Fossil Club? Keith Matlack, all that remained of this help behind the tables, answering questions, partial skull was recovered. showing the local fossils, and basically, be Jean Hooper has donated a recently entertaining! If you can help for even 1-2 discovered partial baleen whale skull from hours either day, contact Mike at 301-424• Little Cove Point Member of the St. Mary's 2602. If you come to help with the club's Formation. In light of the fact that cetacean booth, you get into the show for free (what remains are rare within this formation, this a deal!). specimen may well prove to be important indeed. With her usual humility, she hauled the bulky fossil into my office claiming that she would rather filld petrified wood than trip over whale skulls! If only I were so , unlucky! One of our long time members, Wally Ashby, of Scientists' ChiTs has written an FROM THE CURATOR Stephen Godfrey interesting article on Fossil Shark Teeth on Postage Stamps that is attached to this I am pleased to announce that Mr. Upcoming Events newsletter. Wally had written an earlier Scott Werts is the new Assistant to the article on Fossils on Postage Stamps a fe\\' Curator of Paleontology here at the Calvert Note! CMMFC Dues were due at the fIrst years back and it is great to see he is still Marine Museum. -

Stratigraphic Revision of Upper Miocene and Lower Pliocene Beds of the Chesapeake Group, Middle Atlantic Coastal Plain

Stratigraphic Revision of Upper Miocene and Lower Pliocene Beds of the Chesapeake Group, Middle Atlantic Coastal Plain GEOLOGICAL SURVEY BULLETIN 1482-D Stratigraphic Revision of Upper Miocene and Lower Pliocene Beds of the Chesapeake Group, Middle Atlantic Coastal Plain By LAUCK W. WARD and BLAKE W. BLACKWELDER CONTRIBUTIONS TO STRATIGRAPHY GEOLOGICAL SURVEY BULLETIN 1482-D UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON: 198.0 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR CECIL D. ANDRUS, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY H. William Menard Director Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Ward, Lauck W Stratigraphic revision of upper Miocene and lower Pliocene beds of the Chesapeake group-middle Atlantic Coastal Plain. (Contributions to stratigraphy) (Geological Survey bulletin ; 1482-D) Bibliography: p. Supt. of Docs. no. : I 19.3:1482-D 1. Geology, Stratigraphic-Miocene. 2. Geology, Stratigraphic-Pliocene. 3. Geology- Middle Atlantic States. I. Blackwelder, Blake W., joint author. II. Title. III. Series. IV. Series: United States. Geological Survey. Bulletin ; 1482-D. QE694.W37 551.7'87'0975 80-607052 For sale by Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 CONTENTS Page Abstract __ Dl Introduction 1 Acknowledgments ____________________________ 4 Discussion ____________________________________ 4 Chronology of depositional events ______________________ 7 Miocene Series _________________________________ g Eastover Formation ___________________________ 8 Definition and description ___________________ -

Evolutionary Paleoecology of the Maryland Miocene

The Geology and Paleontology of Calvert Cliffs Calvert Formation, Calvert Cliffs, South of Plum Point, Maryland. Photo by S. Godfrey © CMM A Symposium to Celebrate the 25th Anniversary of the Calvert Marine Museum’s Fossil Club Program and Abstracts November 11, 2006 The Ecphora Miscellaneous Publications 1, 2006 2 Program Saturday, November 11, 2006 Presentation and Event Schedule 8:00-10:00 Registration/Museum Lobby 8:30-10:00 Coffee/Museum Lobby Galleries Open Presentation Uploading 8:30-10:00 Poster Session Set-up in Paleontology Gallery Posters will be up all day. 10:00-10:05 Doug Alves, Director, Calvert Marine Museum Welcome 10:05-10:10 Bruce Hargreaves, President of the CMMFC Welcome Induct Kathy Young as CMMFC Life Member 10:10-10:30 Peter Vogt & R. Eshelman Significance of Calvert Cliffs 10:30-11:00 Susan Kidwell Geology of Calvert Cliffs 11:00-11-15 Patricia Kelley Gastropod Predator-Prey Evolution 11:15-11-30 Coffee/Juice Break 11:30-11:45 Lauck Ward Mollusks 11:45-12:00 Bretton Kent Sharks 12:00-12:15 Michael Gottfried & L. Compagno C. carcharias and C. megalodon 12:15-12:30 Anna Jerve Lamnid Sharks 12:30-2:00 Lunch Break Afternoon Power Point Presentation Uploading 2:00-2:15 Roger Wood Turtles 2:15-2:30 Robert Weems Crocodiles 2:30-2:45 Storrs Olson Birds 2:45-3:00 Michael Habib Morphology of Pelagornis 3:00-3:15 Ralph Eshelman, B. Beatty & D. Domning Terrestrial Vertebrates 3:15-3:30 Coffee/Juice Break 3:30-3:45 Irina Koretsky Seals 3:45-4:00 Daryl Domning Sea Cows 4:00-4:15 Jennifer Gerholdt & S. -

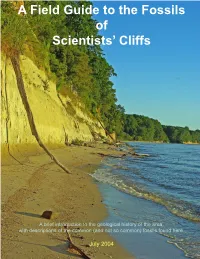

A Field Guide to the Fossils of Scientists' Cliffs

A Field Guide to the Fossils of Scientists’ Cliffs A brief introduction to the geological history of the area, with descriptions of the common (and not so common) fossils found here. July 2004 Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS ............................................................................................................................................ 0 1. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................................... 3 1.1 BACKGROUND ................................................................................................................................................... 3 1.2 OBJECTIVES ...................................................................................................................................................... 4 1.3 SCOPE .............................................................................................................................................................. 4 1.5 APPLICABLE DOCUMENTS ................................................................................................................................. 5 1.6 DOCUMENT ORGANIZATION ............................................................................................................................... 5 2. GEOLOGY .............................................................................................................................................................. 7 2.1 NAMING ROCK/SOIL UNITS ............................................................................................................................... -

The Geology and Vertebrate Paleontology of Calvert Cliffs, Maryland, USA

Smithsonian Institution Scholarly Press smithsonian contributions to paleobiology • number 100 Smithsonian Institution Scholarly Press The Geology and Vertebrate Paleontology of Calvert Cliffs, Maryland, USA Edited by Stephen J. Godfrey SERIES PUBLICATIONS OF THE SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION Emphasis upon publication as a means of “diffusing knowledge” was expressed by the first Secretary of the Smithsonian. In his formal plan for the Institution, Joseph Henry outlined a program that included the follow- ing statement: “It is proposed to publish a series of reports, giving an account of the new discoveries in science, and of the changes made from year to year in all branches of knowledge.” This theme of basic research has been adhered to through the years by thousands of titles issued in series publications under the Smithsonian imprint, commencing with Smithsonian Contributions to Knowledge in 1848 and continuing with the follow- ing active series: Smithsonian Contributions to Anthropology Smithsonian Contributions to Botany Smithsonian Contributions to History and Technology Smithsonian Contributions to the Marine Sciences Smithsonian Contributions to Museum Conservation Smithsonian Contributions to Paleobiology Smithsonian Contributions to Zoology In these series, the Smithsonian Institution Scholarly Press (SISP) publishes small papers and full-scale mono- graphs that report on research and collections of the Institution’s museums and research centers. The Smith- sonian Contributions Series are distributed via exchange mailing lists to libraries, universities, and similar institutions throughout the world. Manuscripts intended for publication in the Contributions Series undergo substantive peer review and eval- uation by SISP’s Editorial Board, as well as evaluation by SISP for compliance with manuscript preparation guidelines (available at www.scholarlypress.si.edu). -

North American Geology, Paleontology, Petrology, and Mineralogy

Bulletin No. 271 Series G, Miscellaneous, 29 DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY CHARLES D. WALCOTT, DiKECTOR BIBLIOGRAPHY AND INDEX OF NORTH AMERICAN GEOLOGY, PALEONTOLOGY, PETROLOGY, AND MINERALOGY FOR THE YE.AR 19O4 BY FIRED BOTJGKHITOIISr WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1905 CONTENTS, Page Letter of transmittal...................................................... 5 Introduction..................'........................................... 7 List of publications examined ............................................. 9 Bibliography..................................... ........................ 15 Classified key to the index................................................ 135 Index................................................................... 143 LETTER OF TRANSMITTAL DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR, UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY, Washington, J). <7., June 7, 1905. SIR: I transmit here with the manuscript of a bibliography and index of North American geology, paleontology, petrology, and mineralogy for the year 1904, and request that it be published as a bulletin of the Survey. Very respectfully, F. B. WEEKS. Hon. CHARLES D. WALCOTT, Director United States Geological Survey. 5 BIBLIOGRAPHY AND INDEX OF NORTH AMERICAN GEOLOGY, PALEONTOLOGY, PETROLOGY, AND MINERALOGY FOR THE YEAR 1904. By FRED BOUGIITON WEEKS. INTRODUCTION. The arrangement of the material of the Bibliography and Index for 1903 is similar to that adopted for the preceding annual bibliographies. Bulletins Nos. 130, 135, 146,149, 156, 162, 172 -

Quarterly Newsletter of the Calvert Marine Museum Fossil Club

QUARTERLY NEWSLETTER OF THE CALVERT MARINE MUSEUM FOSSIL CLUB Volume 3, Number 1 Whole Number 7 Editor: Sandy Roberts Winter 1987 NEW FOSSIL PREPARATION LABORATORY AT CALVERT MARINE MUSEUM A new laboratory for the preparation of fossils has been set up in the former woodworking shop at the Calvert Marine Museum. The dis• placed carpenters, woodcarvers and modelmakers continue to ply their skills in a new building behind the museum. Large glass windows allow visitors to view a nearly complete skeleton of the rare porpoise Hadrodelphis, five additional porpoise skulls, two cetothere (baleen whale) skulls and the partially reassembled carapace of the leather• back turtle Psephophorus. The turtle, on loan from the Smithsonian, is estimated to be over six feet in length and may well be the largest fossil marine turtle ever taken from the Chesapeake formations. On weekends during the month of January Intern student Erik Vogt worked in the laboratory. Erik, a Freshman at Oberlin College, gained experience and course credits for cleaning and restoring the ribs of a sea cow found at Pope's Creek and the skull of a Eurhinodelphis from Parker Creek. CLUB ACTIVITIES Delaware Valley Fossil Club visit On Saturday and Sunday, October 25 and 26, the CW1 fossil club served as host to the Delaware Valley fossil club for several local field trips. After meeting Saturday morning at Matoaka Cottages and hunting there for awhile, both groups went to Chancellor's Point in the afternoon and then to a talk by shark expert Eugenie Clark at Jefferson Patterson park that evening. On Sunday, the more intrepid hunters braved mud and dampness to search at the Camp Roosevelt site. -

Stratigraphic Modeling for Concealed Phosphate Deposits in Virginia's

Stratigraphic Modeling for Concealed Phosphate Deposits in Virginia’s Coastal Plain Virginia Department of Mines, Minerals and Energy Division of Geology and Mineral Resources in cooperation with United States Geological Survey Mineral Resources External Research Program COOPERATIVE AGREEMENT: G10AP00054 FINAL TECHNICAL REPORT Aaron Cross and William L. Lassetter 2011 "Research supported by the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), Department of the Interior, under USGS award number G10AP00054. The views and conclusions contained in this document are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as necessarily representing the official policies, either expressed or implied, of the U.S. Government." “Opportunities for new discoveries are good, and the increasing knowledge about the origin and occurrence of phosphate deposits should aid prospecting.” V. E. McKelvey, 1967 Abstract A study to outline an exploration program for phosphates beneath Virginia’s Coastal Plain was undertaken by the Virginia Division of Geology and Mineral Resources with funding support from the U.S. Geological Survey. An in-depth literature review highlighted the importance of two primary stages in the development of phosphate deposits in the geologic setting of the mid-Atlantic Coastal Plain. During stage one, primary phosphatic material was precipitated in the early Paleogene marine environment from nutrient-rich, oxygen-poor seawater. During stage two, primary phosphate deposits were exposed to weathering, reworked, and concentrated. The model presented here, at its simplest, advocates the concept of a genesis unit, the Paleocene-Eocene Pamunkey Group, bounded on top by an unconformity, which is overlain by the host unit, the Miocene Calvert Formation, whose base contains a lag deposit of phosphatic sand and gravel.