APH-Fall-2017-Issue-1.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NIKE-HERCULES Système D'arme Sol-Air À Longue Portée États-Unis

NIKE-HERCULES Système d’arme sol-air à longue portée États-Unis Genèse du NIKE-HERCULES Le système Nike-Hercules est une évolution du système Nike-Ajax (cf. tableau comparatif des missiles en annexe). L’engin Nike-Hercules (MIM-14) est également un missile à deux étages. Son booster, beaucoup plus puissant (puissance 173.000 livres), lui permet d’être très rapidement supersonique. Après 3,4 secondes, le booster se sépare du missile, ce qui déclenche la mise à feu du second étage ; celui-ci fonctionne pendant 29 secondes et permet au missile d’atteindre une vitesse dépassant Mach 3 et une altitude de 100.000 pieds. Le Nike-Hercules peut emporter une ogive nucléaire ou une ogive conventionnelle. Initialement, la version nucléarisée emportait la tête nucléaire W-7 Mod 2, offrant des puissances de 2,5 ou 28 KT. En 1961, les anciennes ogives furent remplacées par des charges W-31 avec des puissances de 2 KT (Y1) ou 30 KT (Y2). Les dernières versions comportèrent l'ogive W31 Mod2, offrant des puissances de 2 ou 20 KT. En raison de l’efficacité du missile contre certains ICBM, Le Nike-Hercules fut pris en considération dans les accords SALT. Une utilisation sol-sol a été expérimentée en Alaska et appliquée à certaine versions. Le Nike-Hercules a connu une évolution majeure améliorant sa résistance aux contre-mesures électroniques et augmentant sa capacité de détection. Les missiles ainsi modifiés ont été désignés Nike-Hercules Improved (NHI). Système de guidage du Nike-Hercules Déploiements du Nike-Hercules Le Nike-Hercules est entré en service opérationnel en juin 1958 et fut tout d'abord déployé à Chicago. -

Titan Missile Museum and National Historic Landmark

FEATURING PEACE THROUGH DETERRENCE! TITAN MISSILE MUSEUM AND NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK AMERICA’S MOST POWERFUL ICBM! SAHUARITA, AZ titanmissilemuseum.org 2 Peace Through Deterrance JUNIOR MISSILEER HANDBOOK Welcome to the Titan Missile Museum! he Titan Missile Museum Junior Missileer States needed it. Complete as many of the program is designed to help you under activities as you can. When you have finished, Tstand more about what the Titan || one of the docents will sign your certificate and missile was, how it worked, and why the United award your Junior Missileer Badge! Good luck, future Junior Missileer! JUNIOR MISSILEER JUNIOR MISSILEER CODE OF CONDUCT PLEDGE Junior Missileers will Junior Missileers will not touch anything at learn the mission of the the Museum without Titan || — Peace through permission deterrence Junior Missileers treat Junior Missileers will others with respect promote peace through their actions Junior Missileers will thank their Tour Guide at the Junior Missileers will tell end of the Tour at least one other person about what they learned on their visit The Titan Missile Museum is a National Historic Landmark, and the only remaining Titan || missile site open to the public. For more than two decades, Titan II missiles across the United States stood “on alert” 24 hours a day, seven days a week, assuring peace through deterrence. © The Titan Missile Museum Sahuarita/Green Valley, Arizona 520.625.7736 The Junior Missileer Program is funded in part by contributions from the Country Fair White Elephant, Inc. JUNIOR MISSILEER HANDBOOK Peace Through Deterrance 3 Mission of the Titan || Missiles Did you know? n The COLD WAR took place after World withstand the effects of a NEAR MISS War || when the US and former Soviet — an enemy bomb that exploded close by. -

AIRLIFT RODEO a Brief History of Airlift Competitions, 1961-1989

"- - ·· - - ( AIRLIFT RODEO A Brief History of Airlift Competitions, 1961-1989 Office of MAC History Monograph by JefferyS. Underwood Military Airlift Command United States Air Force Scott Air Force Base, Illinois March 1990 TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword . iii Introduction . 1 CARP Rodeo: First Airdrop Competitions .............. 1 New Airplanes, New Competitions ....... .. .. ... ... 10 Return of the Rodeo . 16 A New Name and a New Orientation ..... ........... 24 The Future of AIRLIFT RODEO . ... .. .. ..... .. .... 25 Appendix I .. .... ................. .. .. .. ... ... 27 Appendix II ... ...... ........... .. ..... ..... .. 28 Appendix III .. .. ................... ... .. 29 ii FOREWORD Not long after the Military Air Transport Service received its air drop mission in the mid-1950s, MATS senior commanders speculated that the importance of the new airdrop mission might be enhanced through a tactical training competition conducted on a recurring basis. Their idea came to fruition in 1962 when MATS held its first airdrop training competition. For the next several years the competition remained an annual event, but it fell by the wayside during the years of the United States' most intense participation in the Southeast Asia conflict. The airdrop competitions were reinstated in 1969 but were halted again in 1973, because of budget cuts and the reduced emphasis being given to airdrop operations. However, the esprit de corps engendered among the troops and the training benefits derived from the earlier events were not forgotten and prompted the competition's renewal in 1979 in its present form. Since 1979 the Rodeos have remained an important training event and tactical evaluation exercise for the Military Airlift Command. The following historical study deals with the origins, evolution, and results of the tactical airlift competitions in MATS and MAC. -

Hidden Figures: the American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black

Hidden Figures: the American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helps Win the Space Race by Margot Lee Shetterly An account of the previously unheralded but pivotal contributions of NASA's African- American women mathematicians to America's space program describes how they were segregated from their white counterparts by Jim Crow laws in spite of their groundbreaking successes. Why you'll like it: Science writing, richly detailed, race relations, inspiring. About the Author: Margot Lee Shetterly was born in Hampton, Virginia in 1969. She is a graduate of the University of Virginia's McIntire School of Commerce. After college she worked in investment banking for several years. Her other career moves have included working in the media industry for the website Volume.com, publishing an English language magazine, Inside Mexico; marketing consultant in the Mexican tourism industry; and writing. Hidden Figures is her first book, a New York Times Bestseller and was optioned for a feature film. (Bowker Author Biography) Questions for discussion 1. Hidden Figures uncovers the story of the women whose work at NACA and NASA help shape and define U.S. space exploration. Why is their story significant to our culture, social and scientific history? 2. In what ways does the race for space parallel the civil rights movement? What kind of freedoms are being explored in each? 3. In what ways was Melvin Butler, the white personnel office at Langley, who was searching for qualified mathematicians and wound up hiring black women for jobs that historically had gone only to white men. -

Table of Contents

Pima County’s Multi-species Conservation Plan: Final Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................. iv 1 Introduction to the Pima County Multi-Species Conservation Plan ...................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Purpose and Need for the MSCP ..................................................................... 1 1.2 MSCP Goals and Objectives ............................................................................ 2 1.3 Pima County MSCP: Required Elements ......................................................... 3 1.4 Take ................................................................................................................. 4 2 Planning Area and Background Information ..................................... 6 2.1 Pima County MSCP Planning Area .................................................................. 6 2.2 Collection and Synthesis of Data for the SDCP and MSCP ............................. 6 2.3 Priority Vulnerable Species .............................................................................. 8 2.4 The Maeveen Marie Behan CLS and the Reserve Design Process ................. 8 3 Plan Scope and Anticipated Impacts ............................................... 13 3.1 Permit Area .................................................................................................... 13 3.2 Permit Duration ............................................................................................. -

MARGOT LEE SHETTERLY 46 Bridge Road Brooksville, ME 04617 [email protected] US TEL: + 1 (305) 433-8051

MARGOT LEE SHETTERLY 46 Bridge Road Brooksville, ME 04617 [email protected] www.margotleeshetterly.com US TEL: + 1 (305) 433-8051 CURRENT PROJECTS Hidden Figures , narrative nonfiction work in progress. Hidden Figures is the untold history of the African-American women employed as Human Computers by NACA/NASA from the 1940s through the 1960s. (Represented by Charlotte Sheedy Literary Agency) The Human Computers Project. Multimedia platform archiving the history of NACA-NACA’s African-American Human Computers and their significance in the context of the US Space Program, the Cold War, the Civil Rights Movement and the struggle for Gender Equality. Collaborative work in progress with Prof. Duchess Harris of Macalester College. SKILLS, ACHIEVEMENTS, RECOGNITION • Expansion Magazine’s Entrepreneur of the Year Competition, Finalist (2009). Finalist for prestigious competition held by Mexico’s leading business journal. Nominated as a founder of Inside México Magazine. • Doing It For Ourselves (Donna Ballard, Putnam Berkeley 1997) Featured in book profiling outstanding women of color in finance and business. • Chartered Financial Analyst (CFA) Program . Awarded charter for completion of rigorous three-year course of study and examinations on topics related to corporate finance, investment, and portfolio managementProfiled in major US & Mexican magazines and newspapers as an entrepreneur. • More than 15 years of experience working in start-up media and technology companies • .Robust financial modeling skills • Superb oral, written, and presentation skills in English and Spanish, proficient oral and written French • Computer languages: HTML, HTML5, XML, XHTML, Javascript and Drupal, with a breadth of experience in conceiving, speccing, architecting, producing and managing online platforms MEMBERSHIP ORGANIZATIONS • Member, American Historical Association. -

Rockets of the Armed Forces.Pdf

NUIWX4)- j623.4519 Bk&ro. Bergaust l^OS'lcT; Rockets of the Armed Forces O O u- - "5« ^" CO O PUBLIC LIBRARY Fort Wayne c.r.d Allen County, Indiana 81-1 JT r PUHI I IBRAFU sno IC fflimiivN 3 1833 00476 4350 Rockets of the Armed Forces Between primitive man's rock-hurling days, and modern technology's refined rocket systems, man has come a long way in missile combat. Beginning with the principles of rocketry from early time to the present, Erik Bergaust classifies all forty-two current operational missiles into four basic categories : air-to-air ; air-to-surface ; surface- to-air; and surface-to-surface. From the Navy's highly sophisticated Polaris to the Sidewinder, widely used in Vietnam, the author pinpoints the type, propulsion, guid- ance, performance, and construction of each rocket. A picture and a short paragraph describing each rocket's military use, plus a glossary, are included. Inspection of liquid hydrogen engines. Hydro- gen is a powerful fuel and is often used in combination with liquid oxygen. Fuels are car- ried in the missile in separate tanks and are mixed in the rocket's combustion chamber where the burning takes place. / Bell ROCKETS of the ARMED FORCES By Erik Bergaust 76 6. P. Putnam's Sons New York | 80 260 4 1 ' © 1966 by Erik Bergaust All Rights Reserved Published simultaneously in the Dominion of Canada by Longmans Canada Limited, Toronto Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: AC 66-1025A PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA Second Impression 1430318 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The cooperation of the Office of the Assistant Secre- tary of Defense, Magazine and Book Branch, Directorate of Information Services, made it possible to compile in this book the latest information and data on all opera- tional United States military rockets. -

Department of Defense Office of the Secretary

Monday, May 16, 2005 Part LXII Department of Defense Office of the Secretary Base Closures and Realignments (BRAC); Notice VerDate jul<14>2003 10:07 May 13, 2005 Jkt 205001 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 4717 Sfmt 4717 E:\FR\FM\16MYN2.SGM 16MYN2 28030 Federal Register / Vol. 70, No. 93 / Monday, May 16, 2005 / Notices DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE Headquarters U.S. Army Forces Budget/Funding, Contracting, Command (FORSCOM), and the Cataloging, Requisition Processing, Office of the Secretary Headquarters U.S. Army Reserve Customer Services, Item Management, Command (USARC) to Pope Air Force Stock Control, Weapon System Base Closures and Realignments Base, NC. Relocate the Headquarters 3rd Secondary Item Support, Requirements (BRAC) U.S. Army to Shaw Air Force Base, SC. Determination, Integrated Materiel AGENCY: Department of Defense. Relocate the Installation Management Management Technical Support ACTION: Notice of Recommended Base Agency Southeastern Region Inventory Control Point functions for Closures and Realignments. Headquarters and the U.S. Army Consumable Items to Defense Supply Network Enterprise Technology Center Columbus, OH, and reestablish SUMMARY: The Secretary of Defense is Command (NETCOM) Southeastern them as Defense Logistics Agency authorized to recommend military Region Headquarters to Fort Eustis, VA. Inventory Control Point functions; installations inside the United States for Relocate the Army Contracting Agency relocate the procurement management closure and realignment in accordance Southern Region Headquarters to Fort and related support functions for Depot with Section 2914(a) of the Defense Base Sam Houston. Level Reparables to Aberdeen Proving Ground, MD, and designate them as Closure and Realignment Act of 1990, as Operational Army (IGPBS) amended (Pub. -

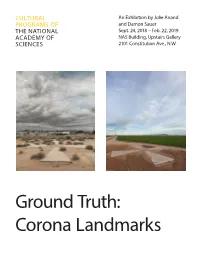

Ground Truth: Corona Landmarks Ground Truth: Corona Landmarks an Introduction

CULTURAL An Exhibition by Julie Anand PROGRAMS OF and Damon Sauer THE NATIONAL Sept. 24, 2018 – Feb. 22, 2019 ACADEMY OF NAS Building, Upstairs Gallery SCIENCES 2101 Constitution Ave., N.W. Ground Truth: Corona Landmarks Ground Truth: Corona Landmarks An Introduction In this series of images of what remains of the Corona project, Julie Anand and Damon Sauer investigate our relationship to the vast networks of information that encircle the globe. The Corona project was a CIA and U.S. Air Force surveillance initiative that began in 1959 and ended in 1972. It involved using cameras on satellites to take aerial photographs of the Soviet Union and China. The cameras were calibrated with concrete targets on the ground that are 60 feet in diameter, which provided a reference for scale and ensured images were in focus. Approximately 273 of these concrete targets were placed on a 16-square-mile grid in the Arizona des- ert, spaced a mile apart. Long after Corona’s end and its declassification in 1995, around 180 remain, and Anand and Sauer have spent three years photographing them as part of an ongoing project. In their images, each concrete target is overpowered by an expansive sky, onto which the artists map the paths of orbiting satellites that were present at the Calibration Mark AG49 with Satellites moment the photograph was taken. For Anand and 2016 Sauer, “these markers of space have become archival pigment print markers of time, representing a poignant moment 55 x 44 inches in geopolitical and technologic social history.” A few of the calibration markers like this one are made primarily of rock rather than concrete. -

89Th Annual Academy Awards® Oscar® Nominations Fact

® 89TH ANNUAL ACADEMY AWARDS ® OSCAR NOMINATIONS FACT SHEET Best Motion Picture of the Year: Arrival (Paramount) - Shawn Levy, Dan Levine, Aaron Ryder and David Linde, producers - This is the first nomination for all four. Fences (Paramount) - Scott Rudin, Denzel Washington and Todd Black, producers - This is the eighth nomination for Scott Rudin, who won for No Country for Old Men (2007). His other Best Picture nominations were for The Hours (2002), The Social Network (2010), True Grit (2010), Extremely Loud & Incredibly Close (2011), Captain Phillips (2013) and The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014). This is the first nomination in this category for both Denzel Washington and Todd Black. Hacksaw Ridge (Summit Entertainment) - Bill Mechanic and David Permut, producers - This is the first nomination for both. Hell or High Water (CBS Films and Lionsgate) - Carla Hacken and Julie Yorn, producers - This is the first nomination for both. Hidden Figures (20th Century Fox) - Donna Gigliotti, Peter Chernin, Jenno Topping, Pharrell Williams and Theodore Melfi, producers - This is the fourth nomination in this category for Donna Gigliotti, who won for Shakespeare in Love (1998). Her other Best Picture nominations were for The Reader (2008) and Silver Linings Playbook (2012). This is the first nomination in this category for Peter Chernin, Jenno Topping, Pharrell Williams and Theodore Melfi. La La Land (Summit Entertainment) - Fred Berger, Jordan Horowitz and Marc Platt, producers - This is the first nomination for both Fred Berger and Jordan Horowitz. This is the second nomination in this category for Marc Platt. He was nominated last year for Bridge of Spies. Lion (The Weinstein Company) - Emile Sherman, Iain Canning and Angie Fielder, producers - This is the second nomination in this category for both Emile Sherman and Iain Canning, who won for The King's Speech (2010). -

Corona KH-4B Satellites

Corona KH-4B Satellites The Corona reconnaissance satellites, developed in the immediate aftermath of SPUTNIK, are arguably the most important space vehicles ever flown, and that comparison includes the Apollo spacecraft missions to the moon. The ingenuity and elegance of the Corona satellite design is remarkable even by current standards, and the quality of its panchromatic imagery in 1967 was almost as good as US commercial imaging satellites in 1999. Yet, while the moon missions were highly publicized and praised, the CORONA project was hidden from view; that is until February 1995, when President Clinton issued an executive order declassifying the project, making the design details, the operational description, and the imagery available to the public. The National Reconnaissance Office (NRO) has a web site that describes the project, and the hardware is on display in the National Air and Space Museum. Between 1960 and 1972, Corona satellites flew 94 successful missions providing overhead reconnaissance of the Soviet Union, China and other denied areas. The imagery debunked the bomber and missile gaps, and gave the US a factual basis for strategic assessments. It also provided reliable mapping data. The Soviet Union had previously “doctored” their maps to render them useless as targeting aids and Corona largely solved this problem. The Corona satellites employed film, which was returned to Earth in a capsule. This was not an obvious choice for reconnaissance. Studies first favored television video with magnetic storage of images and radio downlink when over a receiving ground station. Placed in an orbit high enough to minimize the effects of atmospheric drag, a satellite could operate for a year, sending images to Earth on a timely basis. -

Appendix B Development of Alternatives

Final Environmental Impact Statement for FASTC Nottoway County, Virginia Appendix B Development of Alternatives Appendix B – Development of Alternatives B-1 April 2015 Final Environmental Impact Statement for FASTC Nottoway County, Virginia (This page intentionally left blank) Appendix B – Development of Alternatives B-2 April 2015 Final Environmental Impact Statement for FASTC Nottoway County, Virginia DEVELOPMENT OF ALTERNATIVES The Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ) Regulations for Implementing the Procedural Provisions of the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) establish a number of policies for federal agencies, including “using the NEPA process to identify and assess reasonable alternatives to the Proposed Action that would avoid or minimize adverse effects of these actions on the quality of the human environment.”1 This section provides a detailed description of the development of alternatives. The United States (U.S.) General Services Administration (GSA) and U.S. Department of State (DOS) have undertaken an extensive process in the search for a possible site for the proposed Foreign Affairs Security Training Center (FASTC). A range of alternative sites/locations were evaluated for their potential to meet the needs of the DOS Bureau of Diplomatic Security training program, while having the least impact on the environment. This process and the resulting alternatives carried forward for analysis in the Final EIS are summarized below and discussed in the following sections. Site Selection Process Summary 1. Site Alternatives Considered a. 1993 Site Search b. 2009 Site Search c. 2010 Site Search d. 2013 Additional Due Diligence 2. Build Alternatives Considered a. 2011 Range of alternative layouts on the Fort Pickett/Nottoway County site.