Genomic Imprinting in Mouse Blastocysts Is Predominantly Associated with H3k27me3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of Β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus

Page 1 of 781 Diabetes A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus Robert N. Bone1,6,7, Olufunmilola Oyebamiji2, Sayali Talware2, Sharmila Selvaraj2, Preethi Krishnan3,6, Farooq Syed1,6,7, Huanmei Wu2, Carmella Evans-Molina 1,3,4,5,6,7,8* Departments of 1Pediatrics, 3Medicine, 4Anatomy, Cell Biology & Physiology, 5Biochemistry & Molecular Biology, the 6Center for Diabetes & Metabolic Diseases, and the 7Herman B. Wells Center for Pediatric Research, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN 46202; 2Department of BioHealth Informatics, Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis, Indianapolis, IN, 46202; 8Roudebush VA Medical Center, Indianapolis, IN 46202. *Corresponding Author(s): Carmella Evans-Molina, MD, PhD ([email protected]) Indiana University School of Medicine, 635 Barnhill Drive, MS 2031A, Indianapolis, IN 46202, Telephone: (317) 274-4145, Fax (317) 274-4107 Running Title: Golgi Stress Response in Diabetes Word Count: 4358 Number of Figures: 6 Keywords: Golgi apparatus stress, Islets, β cell, Type 1 diabetes, Type 2 diabetes 1 Diabetes Publish Ahead of Print, published online August 20, 2020 Diabetes Page 2 of 781 ABSTRACT The Golgi apparatus (GA) is an important site of insulin processing and granule maturation, but whether GA organelle dysfunction and GA stress are present in the diabetic β-cell has not been tested. We utilized an informatics-based approach to develop a transcriptional signature of β-cell GA stress using existing RNA sequencing and microarray datasets generated using human islets from donors with diabetes and islets where type 1(T1D) and type 2 diabetes (T2D) had been modeled ex vivo. To narrow our results to GA-specific genes, we applied a filter set of 1,030 genes accepted as GA associated. -

Primate Specific Retrotransposons, Svas, in the Evolution of Networks That Alter Brain Function

Title: Primate specific retrotransposons, SVAs, in the evolution of networks that alter brain function. Olga Vasieva1*, Sultan Cetiner1, Abigail Savage2, Gerald G. Schumann3, Vivien J Bubb2, John P Quinn2*, 1 Institute of Integrative Biology, University of Liverpool, Liverpool, L69 7ZB, U.K 2 Department of Molecular and Clinical Pharmacology, Institute of Translational Medicine, The University of Liverpool, Liverpool L69 3BX, UK 3 Division of Medical Biotechnology, Paul-Ehrlich-Institut, Langen, D-63225 Germany *. Corresponding author Olga Vasieva: Institute of Integrative Biology, Department of Comparative genomics, University of Liverpool, Liverpool, L69 7ZB, [email protected] ; Tel: (+44) 151 795 4456; FAX:(+44) 151 795 4406 John Quinn: Department of Molecular and Clinical Pharmacology, Institute of Translational Medicine, The University of Liverpool, Liverpool L69 3BX, UK, [email protected]; Tel: (+44) 151 794 5498. Key words: SVA, trans-mobilisation, behaviour, brain, evolution, psychiatric disorders 1 Abstract The hominid-specific non-LTR retrotransposon termed SINE–VNTR–Alu (SVA) is the youngest of the transposable elements in the human genome. The propagation of the most ancient SVA type A took place about 13.5 Myrs ago, and the youngest SVA types appeared in the human genome after the chimpanzee divergence. Functional enrichment analysis of genes associated with SVA insertions demonstrated their strong link to multiple ontological categories attributed to brain function and the disorders. SVA types that expanded their presence in the human genome at different stages of hominoid life history were also associated with progressively evolving behavioural features that indicated a potential impact of SVA propagation on a cognitive ability of a modern human. -

Psychosis: a Convergent Functional Genomics Approach Identifying a Series of Candidate Genes for Mania

Identifying a series of candidate genes for mania and psychosis: a convergent functional genomics approach ALEXANDER B. NICULESCU, III, DAVID S. SEGAL, RONALD KUCZENSKI, THOMAS BARRETT, RICHARD L. HAUGER and JOHN R. KELSOE Physiol. Genomics 4:83-91, 2000. You might find this additional information useful... This article cites 52 articles, 15 of which you can access free at: http://physiolgenomics.physiology.org/cgi/content/full/4/1/83#BIBL This article has been cited by 4 other HighWire hosted articles: Evaluation of common gene expression patterns in the rat nervous system S. Kaiser and L. K. Nisenbaum Physiol Genomics, December 16, 2003; 16 (1): 1-7. [Abstract] [Full Text] [PDF] Microarray Technology: A Review of New Strategies to Discover Candidate Vulnerability Downloaded from Genes in Psychiatric Disorders W. E. Bunney, B. G. Bunney, M. P. Vawter, H. Tomita, J. Li, S. J. Evans, P. V. Choudary, R. M. Myers, E. G. Jones, S. J. Watson and H. Akil Am. J. Psychiatry, April 1, 2003; 160 (4): 657-666. [Abstract] [Full Text] [PDF] Biomarker Identification by Feature Wrappers physiolgenomics.physiology.org M. Xiong, X. Fang and J. Zhao Genome Res., November 1, 2001; 11 (11): 1878-1887. [Abstract] [Full Text] [PDF] GRK3 mediates desensitization of CRF1 receptors: a potential mechanism regulating stress adaptation F. M. Dautzenberg, S. Braun and R. L. Hauger Am J Physiol Regulatory Integrative Comp Physiol, April 1, 2001; 280 (4): R935-946. [Abstract] [Full Text] Medline items on this article's topics can be found at http://highwire.stanford.edu/lists/artbytopic.dtl on the following topics: on August 11, 2005 Immunology . -

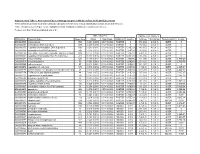

Association of Gene Ontology Categories with Decay Rate for Hepg2 Experiments These Tables Show Details for All Gene Ontology Categories

Supplementary Table 1: Association of Gene Ontology Categories with Decay Rate for HepG2 Experiments These tables show details for all Gene Ontology categories. Inferences for manual classification scheme shown at the bottom. Those categories used in Figure 1A are highlighted in bold. Standard Deviations are shown in parentheses. P-values less than 1E-20 are indicated with a "0". Rate r (hour^-1) Half-life < 2hr. Decay % GO Number Category Name Probe Sets Group Non-Group Distribution p-value In-Group Non-Group Representation p-value GO:0006350 transcription 1523 0.221 (0.009) 0.127 (0.002) FASTER 0 13.1 (0.4) 4.5 (0.1) OVER 0 GO:0006351 transcription, DNA-dependent 1498 0.220 (0.009) 0.127 (0.002) FASTER 0 13.0 (0.4) 4.5 (0.1) OVER 0 GO:0006355 regulation of transcription, DNA-dependent 1163 0.230 (0.011) 0.128 (0.002) FASTER 5.00E-21 14.2 (0.5) 4.6 (0.1) OVER 0 GO:0006366 transcription from Pol II promoter 845 0.225 (0.012) 0.130 (0.002) FASTER 1.88E-14 13.0 (0.5) 4.8 (0.1) OVER 0 GO:0006139 nucleobase, nucleoside, nucleotide and nucleic acid metabolism3004 0.173 (0.006) 0.127 (0.002) FASTER 1.28E-12 8.4 (0.2) 4.5 (0.1) OVER 0 GO:0006357 regulation of transcription from Pol II promoter 487 0.231 (0.016) 0.132 (0.002) FASTER 6.05E-10 13.5 (0.6) 4.9 (0.1) OVER 0 GO:0008283 cell proliferation 625 0.189 (0.014) 0.132 (0.002) FASTER 1.95E-05 10.1 (0.6) 5.0 (0.1) OVER 1.50E-20 GO:0006513 monoubiquitination 36 0.305 (0.049) 0.134 (0.002) FASTER 2.69E-04 25.4 (4.4) 5.1 (0.1) OVER 2.04E-06 GO:0007050 cell cycle arrest 57 0.311 (0.054) 0.133 (0.002) -

A Study of Fez1 and Fez2

Faculty of Health Sciences, Department of Pharmacy Molecular Cancer Research Group A study of Fez1 and Fez2 Establishment of Fez1 and Fez2 knock out cells lines Localization of Fez1 and Fez2 Jenny Thuy Tien Nguyen Acknowledgments This master thesis was carried out at the Molecular Cancer Research Group, Institute of Medical Biology, University of Tromsø – The artic University of Norway from August 2016 to May 2017. It has been a period of intense learning for me, not only in the scientific area, but also on a personal level. Therefore I would like to express my deepest thanks to the people who have supported and helped me throughout this period. I would first like to give my deepest thanks to my main supervisor associate-professor Eva Sjøttem, who has spent time to read my master thesis and has given me constructive feedback, and my lab-supervisor, Hanne Britt Brenne for always finding time to help when it was needed. They were both very generous with their time and knowledge and assisted me during the work with my thesis. Thank you both for your motivation, patience and encouragement. In addition, I would like to thank everyone who has given me some of their time and helped me during this master thesis. Last but not least, I must express my very profound gratitude to my family and friends. Thanks all for the encouragements and supports during my studies. This accomplishment would not have been possible without all of you. And special thanks to my mom, for providing me with unfailing support and continuous encouragement throughout my years of study, I love you mom! Jenny Thuy Tien Nguyen Tromsø, May 2017 I II Abstract Autophagy is an essential cellular process that is important to maintain homeostasis by degrading proteins, lipids and organelles during critical times like cellular or environmental stress conditions. -

Human Social Genomics in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis

Getting “Under the Skin”: Human Social Genomics in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis by Kristen Monét Brown A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Epidemiological Science) in the University of Michigan 2017 Doctoral Committee: Professor Ana V. Diez-Roux, Co-Chair, Drexel University Professor Sharon R. Kardia, Co-Chair Professor Bhramar Mukherjee Assistant Professor Belinda Needham Assistant Professor Jennifer A. Smith © Kristen Monét Brown, 2017 [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0002-9955-0568 Dedication I dedicate this dissertation to my grandmother, Gertrude Delores Hampton. Nanny, no one wanted to see me become “Dr. Brown” more than you. I know that you are standing over the bannister of heaven smiling and beaming with pride. I love you more than my words could ever fully express. ii Acknowledgements First, I give honor to God, who is the head of my life. Truly, without Him, none of this would be possible. Countless times throughout this doctoral journey I have relied my favorite scripture, “And we know that all things work together for good, to them that love God, to them who are called according to His purpose (Romans 8:28).” Secondly, I acknowledge my parents, James and Marilyn Brown. From an early age, you two instilled in me the value of education and have been my biggest cheerleaders throughout my entire life. I thank you for your unconditional love, encouragement, sacrifices, and support. I would not be here today without you. I truly thank God that out of the all of the people in the world that He could have chosen to be my parents, that He chose the two of you. -

CREB-Dependent Transcription in Astrocytes: Signalling Pathways, Gene Profiles and Neuroprotective Role in Brain Injury

CREB-dependent transcription in astrocytes: signalling pathways, gene profiles and neuroprotective role in brain injury. Tesis doctoral Luis Pardo Fernández Bellaterra, Septiembre 2015 Instituto de Neurociencias Departamento de Bioquímica i Biologia Molecular Unidad de Bioquímica y Biologia Molecular Facultad de Medicina CREB-dependent transcription in astrocytes: signalling pathways, gene profiles and neuroprotective role in brain injury. Memoria del trabajo experimental para optar al grado de doctor, correspondiente al Programa de Doctorado en Neurociencias del Instituto de Neurociencias de la Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona, llevado a cabo por Luis Pardo Fernández bajo la dirección de la Dra. Elena Galea Rodríguez de Velasco y la Dra. Roser Masgrau Juanola, en el Instituto de Neurociencias de la Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona. Doctorando Directoras de tesis Luis Pardo Fernández Dra. Elena Galea Dra. Roser Masgrau In memoriam María Dolores Álvarez Durán Abuela, eres la culpable de que haya decidido recorrer el camino de la ciencia. Que estas líneas ayuden a conservar tu recuerdo. A mis padres y hermanos, A Meri INDEX I Summary 1 II Introduction 3 1 Astrocytes: physiology and pathology 5 1.1 Anatomical organization 6 1.2 Origins and heterogeneity 6 1.3 Astrocyte functions 8 1.3.1 Developmental functions 8 1.3.2 Neurovascular functions 9 1.3.3 Metabolic support 11 1.3.4 Homeostatic functions 13 1.3.5 Antioxidant functions 15 1.3.6 Signalling functions 15 1.4 Astrocytes in brain pathology 20 1.5 Reactive astrogliosis 22 2 The transcription -

Insights Into in Vivo Transcription Factor Targeting Through Studies of the Archetypal Zinc Finger Protein

Insights into in vivo transcription factor targeting through studies of the archetypal zinc finger protein KLF3. Jon Burdach A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Biochemistry and molecular genetics School of Biotechnology and Biomolecular Sciences University of New South Wales May 2013 Originality statement 'I hereby declare that this submission is my own work and to the best of my knowledge it contains no materials previously published or written by another person, or substantial proportions of material which have been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma at UNSW or any other educational institution, except where due acknowledgement is made in the thesis. Any contribution made to the research by others, with whom I have worked at UNSW or elsewhere, is explicitly acknowledged in the thesis. I also declare that the intellectual content of this thesis is the product of my own work, except to the extent that assistance from others in the project's design and conception or in style, presentation and linguistic expression is acknowledged.' Signed ·· ~············· · ····· ··· ······HH H Date .... ~/1-lcP.!'f ...... .... ... ...... ......... ... ...... Table of Contents Acknowledgements ........................................................................................................................ i Publications arising from this thesis ............................................................................................. ii Journal articles ............................................................................................................................. -

Quantitative Trait Loci Mapping of Macrophage Atherogenic Phenotypes

QUANTITATIVE TRAIT LOCI MAPPING OF MACROPHAGE ATHEROGENIC PHENOTYPES BRIAN RITCHEY Bachelor of Science Biochemistry John Carroll University May 2009 submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN CLINICAL AND BIOANALYTICAL CHEMISTRY at the CLEVELAND STATE UNIVERSITY December 2017 We hereby approve this thesis/dissertation for Brian Ritchey Candidate for the Doctor of Philosophy in Clinical-Bioanalytical Chemistry degree for the Department of Chemistry and the CLEVELAND STATE UNIVERSITY College of Graduate Studies by ______________________________ Date: _________ Dissertation Chairperson, Johnathan D. Smith, PhD Department of Cellular and Molecular Medicine, Cleveland Clinic ______________________________ Date: _________ Dissertation Committee member, David J. Anderson, PhD Department of Chemistry, Cleveland State University ______________________________ Date: _________ Dissertation Committee member, Baochuan Guo, PhD Department of Chemistry, Cleveland State University ______________________________ Date: _________ Dissertation Committee member, Stanley L. Hazen, MD PhD Department of Cellular and Molecular Medicine, Cleveland Clinic ______________________________ Date: _________ Dissertation Committee member, Renliang Zhang, MD PhD Department of Cellular and Molecular Medicine, Cleveland Clinic ______________________________ Date: _________ Dissertation Committee member, Aimin Zhou, PhD Department of Chemistry, Cleveland State University Date of Defense: October 23, 2017 DEDICATION I dedicate this work to my entire family. In particular, my brother Greg Ritchey, and most especially my father Dr. Michael Ritchey, without whose support none of this work would be possible. I am forever grateful to you for your devotion to me and our family. You are an eternal inspiration that will fuel me for the remainder of my life. I am extraordinarily lucky to have grown up in the family I did, which I will never forget. -

Skeletal Muscle Transcriptome in Healthy Aging

ARTICLE https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-22168-2 OPEN Skeletal muscle transcriptome in healthy aging Robert A. Tumasian III 1, Abhinav Harish1, Gautam Kundu1, Jen-Hao Yang1, Ceereena Ubaida-Mohien1, Marta Gonzalez-Freire1, Mary Kaileh1, Linda M. Zukley1, Chee W. Chia1, Alexey Lyashkov1, William H. Wood III1, ✉ Yulan Piao1, Christopher Coletta1, Jun Ding1, Myriam Gorospe1, Ranjan Sen1, Supriyo De1 & Luigi Ferrucci 1 Age-associated changes in gene expression in skeletal muscle of healthy individuals reflect accumulation of damage and compensatory adaptations to preserve tissue integrity. To characterize these changes, RNA was extracted and sequenced from muscle biopsies col- 1234567890():,; lected from 53 healthy individuals (22–83 years old) of the GESTALT study of the National Institute on Aging–NIH. Expression levels of 57,205 protein-coding and non-coding RNAs were studied as a function of aging by linear and negative binomial regression models. From both models, 1134 RNAs changed significantly with age. The most differentially abundant mRNAs encoded proteins implicated in several age-related processes, including cellular senescence, insulin signaling, and myogenesis. Specific mRNA isoforms that changed sig- nificantly with age in skeletal muscle were enriched for proteins involved in oxidative phosphorylation and adipogenesis. Our study establishes a detailed framework of the global transcriptome and mRNA isoforms that govern muscle damage and homeostasis with age. ✉ 1 National Institute on Aging–Intramural Research Program, National -

Detection of H3k4me3 Identifies Neurohiv Signatures, Genomic

viruses Article Detection of H3K4me3 Identifies NeuroHIV Signatures, Genomic Effects of Methamphetamine and Addiction Pathways in Postmortem HIV+ Brain Specimens that Are Not Amenable to Transcriptome Analysis Liana Basova 1, Alexander Lindsey 1, Anne Marie McGovern 1, Ronald J. Ellis 2 and Maria Cecilia Garibaldi Marcondes 1,* 1 San Diego Biomedical Research Institute, San Diego, CA 92121, USA; [email protected] (L.B.); [email protected] (A.L.); [email protected] (A.M.M.) 2 Departments of Neurosciences and Psychiatry, University of California San Diego, San Diego, CA 92103, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Human postmortem specimens are extremely valuable resources for investigating trans- lational hypotheses. Tissue repositories collect clinically assessed specimens from people with and without HIV, including age, viral load, treatments, substance use patterns and cognitive functions. One challenge is the limited number of specimens suitable for transcriptional studies, mainly due to poor RNA quality resulting from long postmortem intervals. We hypothesized that epigenomic Citation: Basova, L.; Lindsey, A.; signatures would be more stable than RNA for assessing global changes associated with outcomes McGovern, A.M.; Ellis, R.J.; of interest. We found that H3K27Ac or RNA Polymerase (Pol) were not consistently detected by Marcondes, M.C.G. Detection of H3K4me3 Identifies NeuroHIV Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP), while the enhancer H3K4me3 histone modification was Signatures, Genomic Effects of abundant and stable up to the 72 h postmortem. We tested our ability to use H3K4me3 in human Methamphetamine and Addiction prefrontal cortex from HIV+ individuals meeting criteria for methamphetamine use disorder or not Pathways in Postmortem HIV+ Brain (Meth +/−) which exhibited poor RNA quality and were not suitable for transcriptional profiling. -

Table S1. 103 Ferroptosis-Related Genes Retrieved from the Genecards

Table S1. 103 ferroptosis-related genes retrieved from the GeneCards. Gene Symbol Description Category GPX4 Glutathione Peroxidase 4 Protein Coding AIFM2 Apoptosis Inducing Factor Mitochondria Associated 2 Protein Coding TP53 Tumor Protein P53 Protein Coding ACSL4 Acyl-CoA Synthetase Long Chain Family Member 4 Protein Coding SLC7A11 Solute Carrier Family 7 Member 11 Protein Coding VDAC2 Voltage Dependent Anion Channel 2 Protein Coding VDAC3 Voltage Dependent Anion Channel 3 Protein Coding ATG5 Autophagy Related 5 Protein Coding ATG7 Autophagy Related 7 Protein Coding NCOA4 Nuclear Receptor Coactivator 4 Protein Coding HMOX1 Heme Oxygenase 1 Protein Coding SLC3A2 Solute Carrier Family 3 Member 2 Protein Coding ALOX15 Arachidonate 15-Lipoxygenase Protein Coding BECN1 Beclin 1 Protein Coding PRKAA1 Protein Kinase AMP-Activated Catalytic Subunit Alpha 1 Protein Coding SAT1 Spermidine/Spermine N1-Acetyltransferase 1 Protein Coding NF2 Neurofibromin 2 Protein Coding YAP1 Yes1 Associated Transcriptional Regulator Protein Coding FTH1 Ferritin Heavy Chain 1 Protein Coding TF Transferrin Protein Coding TFRC Transferrin Receptor Protein Coding FTL Ferritin Light Chain Protein Coding CYBB Cytochrome B-245 Beta Chain Protein Coding GSS Glutathione Synthetase Protein Coding CP Ceruloplasmin Protein Coding PRNP Prion Protein Protein Coding SLC11A2 Solute Carrier Family 11 Member 2 Protein Coding SLC40A1 Solute Carrier Family 40 Member 1 Protein Coding STEAP3 STEAP3 Metalloreductase Protein Coding ACSL1 Acyl-CoA Synthetase Long Chain Family Member 1 Protein