Open-Source Solutions Overview

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Osgi and GWT Integration Via Pax-Web and Maven (V:0.01)

OSGi and GWT integration via Pax-web and Maven (v:0.01) Sergio Blanco Diez Ignacio Diaz de Sarralde Carvajal January 13, 2010 Contents 1 Introduction 2 2 GWT 3 2.1 Toolkit overview.....................................3 2.1.1 Development overview..............................3 2.1.2 Google Web Toolkit component overview...................4 2.2 Workflow.........................................4 2.2.1 Project creation.................................4 2.2.2 Project structure.................................5 2.2.3 \Hosted" or Development server........................6 2.2.4 Module definition; .gwt.xml files........................8 2.2.5 Coding the client; GWT Widgets........................9 2.2.6 Coding the server; Remote Procedure Calls.................. 12 2.3 Other features...................................... 14 2.3.1 Internationalization............................... 14 2.3.2 Declarative User Interfaces........................... 14 3 OSGi and GWT integration 17 3.1 Creating the GWT Project............................... 17 3.2 Things to consider in GWT Maven projects...................... 20 3.3 Enabling OSGi in the GWT project.......................... 20 3.3.1 Turning the GWT project into a bundle.................... 20 3.3.2 Dependencies management........................... 25 3.3.3 Run using Pax Runner.............................. 28 1 Chapter 1 Introduction When developing complex OSGi applications it is usual to implement one or more web frontends, be them for end users or for consumption by other systems. OSGi provides a standard way to register servlets and resources under different URLs, but creating complex frontends can be dif- ficult and time consuming. When the frontend is SOA based, solutions like Apache CXF help exposing internal services via web services or REST. But if the frontend must be a fairly complex web application in itself, complexity rises. -

Focus on Apache Camel 23 3.1 Classification

Institute of Architecture of Application Systems University of Stuttgart Universitätsstraße 38 D–70569 Stuttgart Diploma Thesis No. 3480 Complete Enterprise Topologies with routing information of Enterprise Services Buses to enable Cloud-migration Andre Grund Course of Study: Software Engineering Examiner: Prof. Dr. Frank Leymann Supervisor: Dipl.-Inf. Tobias Binz Commenced: May 01, 2013 Completed: October 28, 2013 CR-Classification: E.1, K.6 Abstract The Enterprise Service Bus is an important part of todays enterprise IT landscape. It offers the integration of applications build on different platforms without adaptation. This is accomplished by offering message transformation and routing capabilities of client requests to the designated endpoint service. However, Enterprise Service Buses also introduce an additional indirection between the client and the called backend application. Enterprise Topology Graphs capture a snapshot of the whole enterprise IT and are used in various use cases for analysis, migration, adaptation, and optimization of IT. The focus of this work is to enhance the ETG model with structural and statistical information about an enterprise. However, due to the decoupled architecture the information is hidden inside the ESB and not directly accessible. Furthermore, the arrangement and semantics of the routing entities are unknown. The existing ETG Framework includes the automated discovery and maintenance of ETGs, but offers no solution for ESB components in the enterprise IT. This thesis provides an in depth analysis of the ESBs Apache Camel and Apache Synapse. It applies information gathering concepts and evaluate them with a prototypical implementation of an ETG Framework plugin. Using tailored information gathering and presentation methods to enhance ETGs with routing information. -

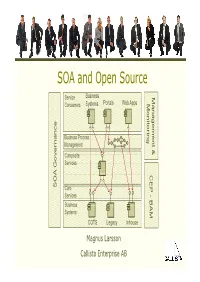

SOA and Open Source

SOA and Open Source Service Business Ma Consumers Systems Portals Web Apps M nageme onitorin g ance Business Process n nn Management t & Composite Services Gover CEP -CEP B AA SO Core Services Business AM Systems COTS Legacy Inhouse Magnus Larsson Callista Enterprise AB Vendor support of Open Source SOA • Vendors provide services for training, consulting and support on selected Open Source SOA products • MuleSource – Over 1000 mission-critical production installations worldwide! – http:// www.mu lesou rce .co m/custo me rs/casestud ies .p hp •WSO2 – http://wso2.com/about/whitepapers/ • Progress FUSE – http://fusesource.com/resources/collateral/ SOA and Open Source Copyright 2009, Callista Enterprise AB Building a SOA Reference Model… Service Business Portals Web Apps Consumers Systems Business Systems COTS Legacy Inhouse SOA and Open Source Copyright 2009, Callista Enterprise AB Building a SOA Reference Model… • Connectivity Service Business - SOAP, Rest, Messaging, Database, FTP… Portals Web Apps Consumers Systems • Transformation - XML, CSV, Fixed Position… • Routing - Header and/or Content based • Enterprise Integration Patterns - Splitting, Aggregation, Resequencing… Core Services Business Systems COTS Legacy Inhouse SOA and Open Source Copyright 2009, Callista Enterprise AB Building a SOA Reference Model… Composite Services Service Business Portals Web Apps Consumers Systems ‐ Course Grained ‐ Internal Messaging High performance access to other services CitComposite Services Core Services Business Systems COTS Legacy Inhouse SOA -

Return of Organization Exempt from Income

OMB No. 1545-0047 Return of Organization Exempt From Income Tax Form 990 Under section 501(c), 527, or 4947(a)(1) of the Internal Revenue Code (except black lung benefit trust or private foundation) Open to Public Department of the Treasury Internal Revenue Service The organization may have to use a copy of this return to satisfy state reporting requirements. Inspection A For the 2011 calendar year, or tax year beginning 5/1/2011 , and ending 4/30/2012 B Check if applicable: C Name of organization The Apache Software Foundation D Employer identification number Address change Doing Business As 47-0825376 Name change Number and street (or P.O. box if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/suite E Telephone number Initial return 1901 Munsey Drive (909) 374-9776 Terminated City or town, state or country, and ZIP + 4 Amended return Forest Hill MD 21050-2747 G Gross receipts $ 554,439 Application pending F Name and address of principal officer: H(a) Is this a group return for affiliates? Yes X No Jim Jagielski 1901 Munsey Drive, Forest Hill, MD 21050-2747 H(b) Are all affiliates included? Yes No I Tax-exempt status: X 501(c)(3) 501(c) ( ) (insert no.) 4947(a)(1) or 527 If "No," attach a list. (see instructions) J Website: http://www.apache.org/ H(c) Group exemption number K Form of organization: X Corporation Trust Association Other L Year of formation: 1999 M State of legal domicile: MD Part I Summary 1 Briefly describe the organization's mission or most significant activities: to provide open source software to the public that we sponsor free of charge 2 Check this box if the organization discontinued its operations or disposed of more than 25% of its net assets. -

Neon Core Infrastructure Services

NeOn-project.org NeOn: Lifecycle Support for Networked Ontologies Integrated Project (IST-2005-027595) Priority: IST-2004-2.4.7 – “Semantic-based knowledge and content systems” D6.4.2 NeOn core infrastructure services Deliverable Co-ordinator: Walter Waterfeld Deliverable Co-ordinating Institution: Software AG (SAG) Other Authors: Diana Maynard, University of Sheffield (USFD), Ian Roberts, University of Sheffield (USFD), Michael Gesmann, Software AG (SAG) Document Identifier: NEON/2010/D6.4.2/v1.0 Date due: October 31st, 2009 Class Deliverable: NEON EU-IST-2005-027595 Submission date: January 31st , 2010 Project start date: March 1, 2006 Version: v1.0 Project duration: 4 years State: Final Distribution: Public 2006–2010 © Copyright lies with the respective authors and their institutions. Page 2 of 25 NeOn Integrated Project EU-IST-027595 NeOn Consortium This document is a part of the NeOn research project funded by the IST Programme of the Commission of the European Communities by the grant number IST-2005-027595. The following partners are involved in the project: Open University (OU) – Coordinator Universität Karlsruhe – TH (UKARL) Knowledge Media Institute – KMi Institut für Angewandte Informatik und Formale Berrill Building, Walton Hall Beschreibungsverfahren – AIFB Milton Keynes, MK7 6AA Englerstrasse 11 United Kingdom D-76128 Karlsruhe, Germany Contact person: Enrico Motta Contact person: Andreas Harth E-mail address: [email protected] E-mail address: [email protected] Universidad Politécnica de Madrid (UPM) Software AG (SAG) Campus de Montegancedo Uhlandstrasse 12 28660 Boadilla del Monte 64297 Darmstadt Spain Germany Contact person: Asunción Gómez Pérez Contact person: Walter Waterfeld E-mail address: [email protected] E-mail address: [email protected] Intelligent Software Components S.A. -

Avaliando a Dívida Técnica Em Produtos De Código Aberto Por Meio De Estudos Experimentais

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DE GOIÁS INSTITUTO DE INFORMÁTICA IGOR RODRIGUES VIEIRA Avaliando a dívida técnica em produtos de código aberto por meio de estudos experimentais Goiânia 2014 IGOR RODRIGUES VIEIRA Avaliando a dívida técnica em produtos de código aberto por meio de estudos experimentais Dissertação apresentada ao Programa de Pós–Graduação do Instituto de Informática da Universidade Federal de Goiás, como requisito parcial para obtenção do título de Mestre em Ciência da Computação. Área de concentração: Ciência da Computação. Orientador: Prof. Dr. Auri Marcelo Rizzo Vincenzi Goiânia 2014 Ficha catalográfica elaborada automaticamente com os dados fornecidos pelo(a) autor(a), sob orientação do Sibi/UFG. Vieira, Igor Rodrigues Avaliando a dívida técnica em produtos de código aberto por meio de estudos experimentais [manuscrito] / Igor Rodrigues Vieira. - 2014. 100 f.: il. Orientador: Prof. Dr. Auri Marcelo Rizzo Vincenzi. Dissertação (Mestrado) - Universidade Federal de Goiás, Instituto de Informática (INF) , Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ciência da Computação, Goiânia, 2014. Bibliografia. Apêndice. Inclui algoritmos, lista de figuras, lista de tabelas. 1. Dívida técnica. 2. Qualidade de software. 3. Análise estática. 4. Produto de código aberto. 5. Estudo experimental. I. Vincenzi, Auri Marcelo Rizzo, orient. II. Título. Todos os direitos reservados. É proibida a reprodução total ou parcial do trabalho sem autorização da universidade, do autor e do orientador(a). Igor Rodrigues Vieira Graduado em Sistemas de Informação, pela Universidade Estadual de Goiás – UEG, com pós-graduação lato sensu em Desenvolvimento de Aplicações Web com Interfaces Ricas, pela Universidade Federal de Goiás – UFG. Foi Coordenador da Ouvidoria da UFG e, atualmente, é Analista de Tecnologia da Informação do Centro de Recursos Computacionais – CERCOMP/UFG. -

Apache Karaf 2.2.3, the Transitive Dependencies for This POM and the Bundles Listed in Src/Main/Resources/ Bundles.Properties

Apache Karaf Version 2.2.3 Apache Karaf Users' Guide 1 Copyright 2011 The Apache Software Foundation 2 Table of contents Overview Quick Start Users Guide Developers Guide 3 Overview 4 OVERVIEW Karaf Overview Apache Karaf is a small OSGi based runtime which provides a lightweight container onto which various components and applications can be deployed. Here is a short list of features supported by the Karaf: • Hot deployment: Karaf supports hot deployment of OSGi bundles by monitoring jar files inside the [home]/deploy directory. Each time a jar is copied in this folder, it will be installed inside the runtime. You can then update or delete it and changes will be handled automatically. In addition, Karaf also supports exploded bundles and custom deployers (Blueprint and Spring ones are included by default). • Dynamic configuration: Services are usually configured through the ConfigurationAdmin OSGi service. Such configuration can be defined in Karaf using property files inside the [home]/etc directory. These configurations are monitored and changes on the properties files will be propagated to the services. • Logging System: using a centralized logging back end supported by Log4J, Karaf supports a number of different APIs (JDK 1.4, JCL, SLF4J, Avalon, Tomcat, OSGi) • Provisioning: Provisioning of libraries or applications can be done through a number of different ways, by which they will be downloaded locally, installed and started. • Native OS integration: Karaf can be integrated into your own Operating System as a service so that the lifecycle will be bound to your Operating System. • Extensible Shell console: Karaf features a nice text console where you can manage the services, install new applications or libraries and manage their state. -

Hypotheses Verification for High Precision Cohesion Metric

International Journal of Computer Science and EngineEngineeringering Open Access Research Paper Volume-2, Issue-4 E-ISSN: 2347-2693 Hypotheses Verification for High Precision Cohesion Metric Kayarvizhy N 1*, Kanmani S 2 and Rhymend Uthariaraj V 3 1*Department of Computer Science and Engineering, AMC Engineering College, India 2 Department of Information Technology, Pondicherry Engineering College, India 3Ramanujan Computing Centre, India www.ijcaonline.org Received: 03/03/2014 Revised: 19/03/2014 Accepted: 15/04/201x4 Published: 30/04/2014 Abstract— Metrics have been used to measure many attributes of software. For object oriented software, cohesion indicates the level of binding of the class elements. A class with high cohesion is one of the desirable properties of a good object oriented design. A highly cohesive class is less prone to faults and is easy to develop and maintain. Several object oriented cohesion metrics have been proposed in the literature. In this paper, we propose a new cohesion metric, the High Precision Cohesion Metric (HPCM) to overcome the limitations of the existing cohesion metrics. We also propose seven hypotheses to investigate the relationship between HPCM and other object oriented metrics. The hypotheses are verified with data collected from 500 classes across twelve open source Java projects. We have used Pearson’s coefficient to analyze the correlation between HPCM and the metrics in the hypotheses. To further bolster our results we have included p-value to confirm the statistical significance of the findings. Keywords—Object Oriented Metrics; Cohesion; High Precision I. INTRODUCTION values. Li and Henry [10] proposed their version of lack of Object oriented design and development continues to be the cohesion (LCOM3) as the number of connected components most widely used methodology for designing high quality in a graph with methods as node and edges between each software. -

Full-Graph-Limited-Mvn-Deps.Pdf

org.jboss.cl.jboss-cl-2.0.9.GA org.jboss.cl.jboss-cl-parent-2.2.1.GA org.jboss.cl.jboss-classloader-N/A org.jboss.cl.jboss-classloading-vfs-N/A org.jboss.cl.jboss-classloading-N/A org.primefaces.extensions.master-pom-1.0.0 org.sonatype.mercury.mercury-mp3-1.0-alpha-1 org.primefaces.themes.overcast-${primefaces.theme.version} org.primefaces.themes.dark-hive-${primefaces.theme.version}org.primefaces.themes.humanity-${primefaces.theme.version}org.primefaces.themes.le-frog-${primefaces.theme.version} org.primefaces.themes.south-street-${primefaces.theme.version}org.primefaces.themes.sunny-${primefaces.theme.version}org.primefaces.themes.hot-sneaks-${primefaces.theme.version}org.primefaces.themes.cupertino-${primefaces.theme.version} org.primefaces.themes.trontastic-${primefaces.theme.version}org.primefaces.themes.excite-bike-${primefaces.theme.version} org.apache.maven.mercury.mercury-external-N/A org.primefaces.themes.redmond-${primefaces.theme.version}org.primefaces.themes.afterwork-${primefaces.theme.version}org.primefaces.themes.glass-x-${primefaces.theme.version}org.primefaces.themes.home-${primefaces.theme.version} org.primefaces.themes.black-tie-${primefaces.theme.version}org.primefaces.themes.eggplant-${primefaces.theme.version} org.apache.maven.mercury.mercury-repo-remote-m2-N/Aorg.apache.maven.mercury.mercury-md-sat-N/A org.primefaces.themes.ui-lightness-${primefaces.theme.version}org.primefaces.themes.midnight-${primefaces.theme.version}org.primefaces.themes.mint-choc-${primefaces.theme.version}org.primefaces.themes.afternoon-${primefaces.theme.version}org.primefaces.themes.dot-luv-${primefaces.theme.version}org.primefaces.themes.smoothness-${primefaces.theme.version}org.primefaces.themes.swanky-purse-${primefaces.theme.version} -

Towards Identifying Software Project Clusters with Regard to Defect Prediction

Towards identifying software project clusters with regard to defect prediction Marian Jureczko, Wroc!aw University of Technology Lech Madeyski, Wroc!aw University of Technology Agenda •! Introduction •! Data acquisition •! Study design •! Results •! Conclusions Introduction Motivation – Why defect prediction? 20% of classes contain 80% of defects We can use the software metrics to predict error prone classes and therefore prioritize and optimize tests. Motivation – Why clustering projects? •! Defect prediction is sometime impossible because lack of training data: –! It may be the first release of a project –! The company or the project may be to small to afford collecting training data •! With well defined project clusters the cross-project defect prediction will be possible Definitions •!Defect -! Interpreted as a defect in the investigated project -! Commented in the version control system (CVS or SVN) •!Defect prediction model Values of Metrics for a given java class Estimated •!WMC = ... Number •!DIT = ... Model of •!NOC = ... •!CBO = ... Defects •!RFC = … •!LCOM = … •!Ca=... •!.... Data acquisition •! 19 different metrics were calculated with the CKJM tool (http://gromit.iiar.pwr.wroc.pl/p_inf/ckjm) •! Chidamber & Kemerer metrics suite •! QMOOD metrics suite •! Tang, Kao and Chen’s metrics (C&K quality oriented extension) •! Cyclomatic Complexity, LCOM3, Ca, Ce and LOC •! Defects were collected with BugInfo ( http://kenai.com/projects/buginfo) Compare CVS/SVN Bug CVS log against given & SVN regular expression metrics repository Data -

Kuali Student Service System: Technical Architecture Phase 1 Recommendations

Kuali Student Service System Technical Architecture Phase 1 Recommendations Kuali Student Service System Technical Architecture Phase 1 Recommendations December 31 2007 Kuali Student Technical Team Technical Architecture Phase 1 deliverables 2/14/2008 1 Kuali Student Service System Technical Architecture Phase 1 Recommendations Table of Contents 1 OVERVIEW ........................................................................................................................ 4 1.1 REASON FOR THE INVESTIGATION ................................................................................... 4 1.2 SCOPE OF THE INVESTIGATION ....................................................................................... 4 1.3 METHODOLOGY OF THE INVESTIGATION .......................................................................... 4 1.4 CONCLUSIONS ............................................................................................................... 5 1.5 DECISIONS THAT HAVE BEEN DELAYED ............................................................................ 6 2 STANDARDS ..................................................................................................................... 7 2.1 INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................. 7 2.2 W3C STANDARDS .......................................................................................................... 7 2.3 OASIS STANDARDS ...................................................................................................... -

TE Console 8.8.2.2 - Use of Third-Party Libraries

TE Console 8.8.2.2 - Use of Third-Party Libraries Name Selected License mindterm 4.2.2 (Commercial) APPGATE-Mindterm-License GifEncoder 1998 (Acme.com License) Acme.com Software License ImageEncoder 1996 (Acme.com License) Acme.com Software License commons-discovery 0.2 [Bundled w/te-console] Apache License 1.1 (Apache 1.1) jrcs 20080310 (Apache 1.1) Apache License 1.1 activemQ-broker 5.13.2 (Apache-2.0) Apache License 2.0 activemQ-broker 5.15.9 (Apache-2.0) Apache License 2.0 activemQ-camel 5.15.9 (Apache-2.0) Apache License 2.0 activemQ-client 5.13.2 (Apache-2.0) Apache License 2.0 activemQ-client 5.14.2 (Apache-2.0) Apache License 2.0 activemQ-client 5.15.9 (Apache-2.0) Apache License 2.0 activemQ-jms-pool 5.15.9 (Apache-2.0) Apache License 2.0 activemQ-kahadb-store 5.15.9 (Apache-2.0) Apache License 2.0 activemQ-openwire-legacy 5.13.2 (Apache-2.0) Apache License 2.0 activemQ-openwire-legacy 5.15.9 (Apache-2.0) Apache License 2.0 activemQ-pool 5.15.9 (Apache-2.0) Apache License 2.0 activemQ-protobuf 1.1 (Apache-2.0) Apache License 2.0 activemQ-spring 5.15.9 (Apache-2.0) Apache License 2.0 activemQ-stomp 5.15.9 (Apache-2.0) Apache License 2.0 ant 1.6.3 (Apache 2.0) Apache License 2.0 avalon-framework 4.2.0 (Apache v2.0) Apache License 2.0 awaitility 1.7.0 (Apache-2.0) Apache License 2.0 axis 1.4 [Bundled w/te-console] (Apache v2.0) Apache License 2.0 axis-jaxrpc 1.4 [Bundled w/te-console] (Apache 2.0) Apache License 2.0 axis-saaj 1.4 [Bundled w/te-console] (Apache 2.0) Apache License 2.0 batik 1.6 (Apache v2.0) Apache License 2.0 batik-constants