2011-07-19 Paper

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Retail Change: a Consideration of the UK Food Retail Industry, 1950-2010. Phd Thesis, Middlesex University

Middlesex University Research Repository An open access repository of Middlesex University research http://eprints.mdx.ac.uk Clough, Roger (2002) Retail change: a consideration of the UK food retail industry, 1950-2010. PhD thesis, Middlesex University. [Thesis] This version is available at: https://eprints.mdx.ac.uk/8105/ Copyright: Middlesex University Research Repository makes the University’s research available electronically. Copyright and moral rights to this work are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners unless otherwise stated. The work is supplied on the understanding that any use for commercial gain is strictly forbidden. A copy may be downloaded for personal, non-commercial, research or study without prior permission and without charge. Works, including theses and research projects, may not be reproduced in any format or medium, or extensive quotations taken from them, or their content changed in any way, without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder(s). They may not be sold or exploited commercially in any format or medium without the prior written permission of the copyright holder(s). Full bibliographic details must be given when referring to, or quoting from full items including the author’s name, the title of the work, publication details where relevant (place, publisher, date), pag- ination, and for theses or dissertations the awarding institution, the degree type awarded, and the date of the award. If you believe that any material held in the repository infringes copyright law, please contact the Repository Team at Middlesex University via the following email address: [email protected] The item will be removed from the repository while any claim is being investigated. -

Your Town Audit Stevenston

Your Town Audit: Stevenston November 2016 Photos by EKOS unless otherwise stated. Map Data © Google 2016 Contents 1. Understanding Scottish Places Summary 1 2. Accessible Town Centre 3 3. Active Town Centre 5 4. Attractive Town Centre 11 5. YTA Summary and Key Points 14 Report produced by: Audit Date: October 2016 Draft report: 2 December 2016 For: North Ayrshire Council Direct enquiries regarding this report should be submitted to: Liam Turbett, EKOS, 0141 353 8327 [email protected] Rosie Jenkins, EKOS, 0141 353 8322 [email protected] 1. Understanding Scottish Places Summary This report presents a summary of the Your Town Audit (YTA) for Stevenston, conducted by Scotland’s Towns Partnership and EKOS. The detailed YTA Framework and Data Workbook are provided under separate cover. The YTA was developed to provide a framework to measure and monitor the performance of Scotland’s towns and town centres using a series of Key Performance Indicators. It provides a comprehensive audit of Stevenston with data on up to 180 KPIs across seven themes – Locality, Accessibility, Local Services, Activities + Events, Development Capacity, Tourism, and Place + Quality Impressions. The Understanding Scottish Places (USP) data platform provides a summary analysis for Largs and identifies eight comparator towns that have similar characteristics, with the most similar being Auchinleck, Denny, Maybole, and Alness.1 The USP platform – www.usp.scot – describes Saltcoats in the following general terms: Stevenston’s Interrelationships: an ‘interdependent to independent town’, which means it has a good number of assets in relation to its population. Towns of this kind have some diversity of jobs; and residents travel a mix of short and long distances to travel to work and study. -

Pdf Shop 'Celtic Gold' in Peel

No. 129 Spring 2004/5 €3.00 Stg£2.50 • SNP Election Campaign • ‘Property Fever’ on Breizh • The Declarationof the Bro Gymraeg • Istor ar C ’herneveg • Irish Language News • Strategy for Cornish • Police Bug Scandal in Mann • EU Constitution - Vote No! ALBA: COM.ANN CEILTFACH * BREIZH: KFVTCF KELT1EK * CYMRU: UNDEB CELTA DD * EIRE: CON RAD H GEILTE AC H * KERNOW: KtBUNYANS KELTEK * MANNIN: COMlVbtYS CELTIAGH tre na Gàidhlig gus an robh e no I a’ dol don sgoil.. An sin bhiodh a’ huile teasgag tre na Gàidhlig air son gach pàiste ann an Alba- Mur eil sinn fhaighinn sin bidh am Alba Bile Gàidhlig gun fheum. Thuig Iain Trevisa gun robh e feumail sin a dhèanamh. Seo mar a sgrìohh e sa bhli adhna 1365, “...dh’atharraich Iain à Còm, maighstir gramair, ionnsachadh is tuigsinn gramair sna sgoiltean o’n Fhraingis gu TEACASG TRE NA GÀIDHLIG Beurla agus dh’ionnsaich Richard Pencrych an aon scòrsa theagaisg agus Abajr gun robh sinn toilichte cluinntinn Inbhirnis/Inverness B IVI 1DR... fon feadhainn eile à Pencrych; leis a sin, sa gun bidh faclan Gaidhlig ar na ceadan- 01463-225 469 e-mail [email protected] bhliadhna don Thjgheama Againn” 1385, siubhail no passports again nuair a thig ... tha cobhair is fiosrachadh ri fhaighinn a an naodhamh bliadhna do’n Righ Richard ceann na bliadhna seo no a dh’ aithgheor thaobh cluich sa Gàidhlig ro aois dol do an dèidh a’Cheannsachaidh anns a h-uile 2000. Direach mar a tha sinn a’ dol thairis sgoil, Bithidh an t-ughdar is ionadail no sgoil gràmair feadh Sasunn, tha na leana- air Caulas na Frainge le bata no le trean -

Somerfield Plc / Wm Morrison Supermarkets Plc Inquiry

Somerfield plc and Wm Morrison Supermarkets plc A report on the acquisition by Somerfield plc of 115 stores from Wm Morrison Supermarkets plc September 2005 Members of the Competition Commission who conducted this inquiry Christopher Clarke (Chairman of the Group) Nicholas Garthwaite Christopher Goodall Robert Turgoose Professor Stephen Wilks FCA Chief Executive and Secretary of the Competition Commission Martin Stanley Note by the Competition Commission The Competition Commission has excluded from this report information which the inquiry group considers should be excluded having regard to the three considerations set out in section 244 of the Enterprise Act 2002. The omissions are indicated by []. © Competition Commission 2005 Web site: www.competition-commission.org.uk The acquisition by Somerfield plc of 115 stores from Wm Morrison Supermarkets plc Contents Page Summary................................................................................................................................. 3 Findings .................................................................................................................................. 6 1. The reference.............................................................................................................. 6 2. The companies............................................................................................................ 6 The merger transaction ............................................................................................... 8 Rationale for the merger -

A STUDY of the EVOLUTION of CONCENTRATION in the FOOD DISTRIBUTION INDUSTRY for the UNITED KINGDOM October 1977

COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES A STUDY OF THE EVOLUTION OF CONCENTRATION IN THE FOOD DISTRIBUTION INDUSTRY FOR THE UNITED KINGDOM October 1977 In 1970 the Commission initiated a research programme on the evolution of concen tration and com petition in several sectors and markets of manufacturing industries in the different Member States (textile, paper, pharmaceutical and photographic pro ducts, cycles and motorcycles, agricultural machinery, office machinery, textile machinery, civil engineering equipment, hoisting and handling equipment, electronic and audio equipment, radio and television receivers, domestic electrical appliances, food and drink manufacturing industries). The aims, criteria and principal results of this research are set out in the document "M ethodology of concentration analysis applied to the study o f industries and markets” , by Dr. Remo LINDA, (ref. 8756), September 1976. This particular volume constitutes a part of the second series of studies, the main aims of which is to present the results of the research on the evolution of concentration in the food distribution industry for the United Kingdom. Another volume, already published (vol. II: Price Surveys), outlines the results of the research on the distribution o f food products in the United Kingdom, w ith regard to the evolution of prices and mark-ups, based on a limited sample of food products and on a limited number of sales points in the Greater London area. Similar volumes concerning the structures of the distributive systems and the evolution of prices and mark ups have been established also fo r other Member States (Germany, France, Italy and Denmark). COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES A STUDY OF THE EVOLUTION OF CONCENTRATION IN THE FOOD DISTRIBUTION INDUSTRY FOR THE UNITED KINGDOM VOLUME I Industry structure and concentration by Development Analysts Ltd., 49 Lower Addiscombe Road, Croydon, CRO 6PQ, England. -

Razvoj Diskontnih Prodajaln V Sloveniji

UNIVERZA V LJUBLJANI EKONOMSKA FAKULTETA DIPLOMSKO DELO RAZVOJ DISKONTNIH PRODAJALN V SLOVENIJI Ljubljana, junij 2005 MATEJA OREŠNIK IZJAVA Študentka Mateja Orešnik izjavljam, da sem avtorica tega diplomskega dela, ki sem ga napisala pod mentorstvom dr. Danijela Starmana in dovolim objavo diplomskega dela na fakultetnih spletnih straneh. V Ljubljani, dne 9.6.2005 Podpis: KAZALO 1. UVOD ................................................................................................................................ 1 2. ANALIZA STRATEŠKIH USMERITEV SLOVENSKIH TRGOVCEV.................. 2 2.1. SPLOŠNE ZNA ČILNOSTI SVETOVNE TRGOVINE............................................ 2 2.2. STRATEGIJE SLOVENSKIH TRGOVSKIH PODJETIJ........................................ 4 3. RAZVOJ DISKONTNE PRODAJE V EVROPI .......................................................... 6 3.1. OPREDELITEV DISKONTNE PRODAJE .............................................................. 6 3.1.1. »HARD DISKONT« (prodajalna z omejeno ponudbo)..................................... 6 3.1.2. »SOFT DISKONT« (prodajalna z razširjeno ponudbo) .................................... 6 3.2. RAZVOJ DISKONTNIH PRODAJALN................................................................... 7 3.2.1. RAZVOJNE STOPNJE...................................................................................... 9 3.2.2. INTERNACIONALIZACIJA POSLOVANJA ............................................... 11 3.2.3. POMEN EKONOMIJE OBSEGA................................................................... 12 3.3. -

Somerfield Plc / Wm Morrison Supermarkets Plc Inquiry

APPENDIX B Key aspects of the economic analysis for Stage 1 of the local competitive effects methodology Part 1 Introduction 1. Stage 1 of our local competitive effects methodology involves identifying a local market in which to apply a screening rule. The local market has a product-market dimension (ie which fascias and sizes of store compete with each other) and a geographic-market dimension (ie how wide their customer catchment areas are). This appendix summarizes four key aspects of the economic analysis undertaken at Stage 1. 2. Our findings are that: • the product market used at Stage 1: — should not include the LADs, ie Aldi, Lidl and Netto, nor Marks & Spencer; but — should include all stores of 280 sq metres (3,000 sq feet) or more (including one-stop shops); • the geographic market used at Stage 1 should use 5-minute drive-time isochrones for urban stores and 10-minute drive-time isochrones for rural stores; and • in circumstances where an acquired store’s local market share was higher pre- merger (ie where it appears to have faced less competition) its margins also tended to be higher, especially in rural areas. A corollary of this result is that the local markets for which acquired stores’ market shares have been calculated by Somerfield may be relevant markets, especially in rural areas. 3. The remainder of this appendix is organized as follows. Part 2 reports the results of an analysis of the impact on Somerfield and Kwik Save sales of the opening of various competitor fascias, which helps to define the product market (ie which competing fascias constrain Somerfield and Kwik Save). -

Evidence from UK Food Retailing De Ce O U Ood Eta G

Do SSlales MMtt?atter? Eviden ce fr om UK F ood R etailing Tim Lloyd , Wyn Morgan, Steve McCorriston and Evious Zgovu Paper prepared for the INRA-IDEI Semi nar, “Competiti on and Strat egi ies in the Ret aili ng Ind ust ry” , Toulouse School of Economics, 16/17 May 2011. Funding from the European Union Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013) under grant agreement no. 265601 is gratefully acknowledged. The results reflect the views of the authors only. Motivation and Aims Supermarkets have come to dominate the retail landscape A distinctive feature of supermarket prices is the prominent use of discounting (‘sales’) in price variation Variation in food prices is important at two levels: Macro-economic: . Retail price inflation Microeconom ic: . Sales as a competitive tool in imperfectly competitive markets Nielsen Scantrack© : scanner dataset of 230,000 prices Literature Literature on retail price dynamics: . relatively recent and growing with the availability of new microdata sources (Maćkowiak and Smets 2008, Dhyne et al. 2006) . empirical evidence does not sit easily with standard theory (Nakamura and Steinsson 2008, Berck et al. 2008) . emphasises the role of retailer (not manufacturer) in price setting (Chevalier et al. 2003, Nakamura 2008,) . downplays cost shocks as principal source of variation (Nakamura 2008) . importance of sales in price variability (20-50%) (Pesendorfer 2000, Hosken and Reiffen 2004, Berck et al. 2008, Naaakamu uaadra and Steinsso n2008) Heterogeneity a recurrent theme Contribution We focus on sales in retail price dynamics in food sector, relatively few studies, particularly in EU . Are sales less important in EU than US? . -

A Case-Study of Kwik Save Group P.L.C

Spatial-Structural Relationships in Retail corporate Growth: A Case-Study of Kwik Save Group P.L.C. by Leigh Sparks* Retail companies develop and expand by combining both struc- tural attributes and spatial awareness. The spatial-structural development and growth of individual retail companies has been neglected in the growing retail literature. Through examin- ing in detail the growth and development of retail companies, concentrating on both the spatial and structural dimensions of development ad using the concepts and ideas emerging in cognate fields such as entrepreneurship, competitive strategy and innovation diffusion, it is postulated that a better under- standing of the complexities of retail growth will be produced. A case-study of Kwik Save Group P.L.C. is used here to explore these concepts, to build a spatial-structural theory of retail change and to demonstrate the relevance and usefulness of detailed study of individual firm. INTRODUCTION 'Every marketing strategy leaves a spatial imprint' [Jones and Simmons, 1987: 331.1. Retail companies operate in both a business and a spatial environment. It has often been claimed that location is crucial to retailing,, but it is equally true that the retail offering and operation has to fit both the marketing and the wider competitive environment. Retail businesses develop by considering both the spatial and the structural elements of the company and the environment. Retailers have to determine what and how they are going to retail, where outlets are to be located in respect of the market and the competition and how the retail operations are going to be organised. -

Price Variation with Around 40 Per Cent of Price Variation

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Bournemouth University Research Online Do Sales Matter?: Evidence from UK Food Retailing T.A. Lloyd*, C.W. Morgan*, S. McCorriston** and E. Zgovu* Abstract This paper assesses the role of sales as a feature of price dynamics using scanner data. The study analyses an extensive, high frequency panel of supermarket prices consisting of over 230,000 weekly price observations on around 500 products in 15 categories of food stocked by the UK’s seven largest retail chains. In all, 1,700 weekly time series are available at the barcode-specific level including branded and own-label products. The data allows the frequency, magnitude and duration of sales to be analysed in greater detail than has hitherto been possible with UK data. The main results are: (i) sales are a key feature of aggregate price variation with around 40 per cent of price variation being accounted for by sales once price differences for each Unique Product Code (UPC) level across the major retailers are accounted for; (ii) there is considerable heterogeneity in the use of sales across retailers; (iii) much of the price variation that is observed in the UK food retailing sector is accounted for by price differences between retailers; (iv) only a small proportion of price variation that is observed in UK food retailing is common across the major retailers suggesting that cost shocks originating at the manufacturing level is not one of the main sources of price variation in the UK; (v) own-label products also exhibit considerable sales behaviour though this is less important than sales for branded goods; and (vi) there is some evidence of coordination in the timing of sales across retailers insofar as the probability of a sale at the UPC level at a given retailer increases if the product is also on sale at another retailer. -

Focus on Convenience Trading

Focus on Convenience Trading Background to voluntarily purchase most of their petrol sold. The net result is that unit Forced to lower petrol prices, Murco solutions to customers’ needs right INTRODUCTION Murco and SPAR goods from one retail distributor in costs at neighbourhood stations are was faced with three problems: on their doorsteps. While shoppers return for beneficial terms resulting higher than at trunk road locations, inevitably would do their weekly pur- reduced petrol margins In the closing decade of the 20th century, the UK retailing industry has Murco from economies of scale. They also unless relatively high non-fuel sales chasing at the large supermarket, they witnessed massive change mainly due to an increasing domination of Murco is the UK subsidiary of Murphy benefit from enhanced marketing are achieved. reduced petrol volumes might be enticed to fill mid-week gaps major supermarket chains. Fundamental developments include: Oil Corporation of the USA and sup- impact, trading under one name, by ‘topping up’ at neighbourhood Consequently, Murco had developed reduced shop sales. plies 400 service stations in England which has since become the premier stores. the continuing decline of the corner shop its stations to cater for the local market and Wales. brand in convenience and neighbour- Income had fallen and unit costs had with small convenience stores operated By developing its forecourt shops into the disappearance of the filling station selling just petrol and oil. hood retailing. increased. Murco’s UK system is based around by self-employed proprietors recruited stores capable of intercepting this mid- Organisations have seen a need to make appropriate responses to In 1957, five wholesalers applied to from the local area. -

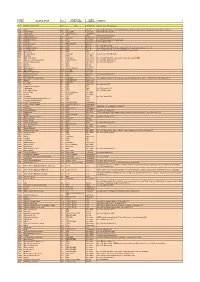

ANMW Retail Multiple Classifications

ANMW ANMW RETAIL ANMW MULTIPLE GROUP Status COMMENTS CODE CLASSIFICATIONS CATEGORY AFS Amazon Fresh Stores Live CON Convenience Code live from 16th Jul 2021 ALD Aldi Live SUP Grocery Live 21st November 2011 - from 13th April 2015 - Class from MIS to SUP, Category from Other RMG to Grocery ALE Aleef Garages Live CFC / SER Forecourts Revived 7th February 2011 AFJ Alfred Jones Live CON/CCC/CFC Convenience AAS Alpha Airports Live ITP Travel Revived 28th August 2009 APW Appleby Westwood Live CON/CCC Convenience Live 1st February 2010 APL Applegreen Stores Live CFC Forecourts Live 29th November 2010 - Ireland Only ARA Aramark Live CAP Convenience Live 31st March 2008 ASP Asda Forecourts Live PFC/CFC/SER Grocery ASL Asda Living Live CAP Grocery Live 1st February 2010 ASN Asda Supermarkets Live CCC Grocery Live 29th November 2010 : Name updated from 7th Jan, previously ASDA - NETTO ASD Asda Superstores Live SUP Grocery Name updated from 7th Jan, previously ASDA - Supermarkets BAN Bailey News Live CTN CTN BES Bestways Retail Live CON/CCC Convenience Code live from 16th Mar 2020 BLK Blackwells Live MSN Other RMG TAT Blakemore Retail Live CON/CCC Convenience Live from 28th May 2012 - Just a name change previously TATES BRI Blakemore Retail Independents Live CON/CFC/PFC Convenience Live from 20th October 2014 BGC Blooms Garden Centres Live MIS Other RMG Live from 13th March 2017 BTH Booths Live SUP Grocery BOO Boots Plc Live MSN High Street BOU Bourne Leisure Live Refer to class list Other RMG BPC BP Connect Live CFC/SER Forecourts BPS BP M&S Simply