Coming out in East Germany, by Kyle Frackman

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A History of German-Scandinavian Relations

A History of German – Scandinavian Relations A History of German-Scandinavian Relations By Raimund Wolfert A History of German – Scandinavian Relations Raimund Wolfert 2 A History of German – Scandinavian Relations Table of contents 1. The Rise and Fall of the Hanseatic League.............................................................5 2. The Thirty Years’ War............................................................................................11 3. Prussia en route to becoming a Great Power........................................................15 4. After the Napoleonic Wars.....................................................................................18 5. The German Empire..............................................................................................23 6. The Interwar Period...............................................................................................29 7. The Aftermath of War............................................................................................33 First version 12/2006 2 A History of German – Scandinavian Relations This essay contemplates the history of German-Scandinavian relations from the Hanseatic period through to the present day, focussing upon the Berlin- Brandenburg region and the northeastern part of Germany that lies to the south of the Baltic Sea. A geographic area whose topography has been shaped by the great Scandinavian glacier of the Vistula ice age from 20000 BC to 13 000 BC will thus be reflected upon. According to the linguistic usage of the term -

University of Birmingham Museum, Furniture

University of Birmingham Museum, furniture, men McTighe, Trish DOI: 10.3138/MD.3053 License: None: All rights reserved Document Version Peer reviewed version Citation for published version (Harvard): McTighe, T 2017, 'Museum, furniture, men: the Queer ecology of I Am My Own Wife', Modern Drama, vol. 60, no. 2, pp. 150-168. https://doi.org/10.3138/MD.3053 Link to publication on Research at Birmingham portal Publisher Rights Statement: Checked 24/11/2016 General rights Unless a licence is specified above, all rights (including copyright and moral rights) in this document are retained by the authors and/or the copyright holders. The express permission of the copyright holder must be obtained for any use of this material other than for purposes permitted by law. •Users may freely distribute the URL that is used to identify this publication. •Users may download and/or print one copy of the publication from the University of Birmingham research portal for the purpose of private study or non-commercial research. •User may use extracts from the document in line with the concept of ‘fair dealing’ under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 (?) •Users may not further distribute the material nor use it for the purposes of commercial gain. Where a licence is displayed above, please note the terms and conditions of the licence govern your use of this document. When citing, please reference the published version. Take down policy While the University of Birmingham exercises care and attention in making items available there are rare occasions when an item has been uploaded in error or has been deemed to be commercially or otherwise sensitive. -

Museum, Furniture, Men: the Queer Ecology of I Am My Own Wife Mctighe, Trish

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Birmingham Research Portal Museum, Furniture, Men: The Queer Ecology of I Am My Own Wife McTighe, Trish DOI: 10.3138/MD.3053 License: None: All rights reserved Document Version Peer reviewed version Citation for published version (Harvard): McTighe, T 2017, 'Museum, Furniture, Men: The Queer Ecology of I Am My Own Wife', Modern Drama, vol. 60, no. 2, pp. 150-168. https://doi.org/10.3138/MD.3053 Link to publication on Research at Birmingham portal Publisher Rights Statement: Checked 24/11/2016 General rights Unless a licence is specified above, all rights (including copyright and moral rights) in this document are retained by the authors and/or the copyright holders. The express permission of the copyright holder must be obtained for any use of this material other than for purposes permitted by law. •Users may freely distribute the URL that is used to identify this publication. •Users may download and/or print one copy of the publication from the University of Birmingham research portal for the purpose of private study or non-commercial research. •User may use extracts from the document in line with the concept of ‘fair dealing’ under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 (?) •Users may not further distribute the material nor use it for the purposes of commercial gain. Where a licence is displayed above, please note the terms and conditions of the licence govern your use of this document. When citing, please reference the published version. -

Max Planck Institute for the History of Science Werner Heisenberg And

MAX-PLANCK-INSTITUT FÜR WISSENSCHAFTSGESCHICHTE Max Planck Institute for the History of Science PREPRINT 203 (2002) Horst Kant Werner Heisenberg and the German Uranium Project Otto Hahn and the Declarations of Mainau and Göttingen Werner Heisenberg and the German Uranium Project* Horst Kant Werner Heisenberg’s (1901-1976) involvement in the German Uranium Project is the most con- troversial aspect of his life. The controversial discussions on it go from whether Germany at all wanted to built an atomic weapon or only an energy supplying machine (the last only for civil purposes or also for military use for instance in submarines), whether the scientists wanted to support or to thwart such efforts, whether Heisenberg and the others did really understand the mechanisms of an atomic bomb or not, and so on. Examples for both extreme positions in this controversy represent the books by Thomas Powers Heisenberg’s War. The Secret History of the German Bomb,1 who builds up him to a resistance fighter, and by Paul L. Rose Heisenberg and the Nazi Atomic Bomb Project – A Study in German Culture,2 who characterizes him as a liar, fool and with respect to the bomb as a poor scientist; both books were published in the 1990s. In the first part of my paper I will sum up the main facts, known on the German Uranium Project, and in the second part I will discuss some aspects of the role of Heisenberg and other German scientists, involved in this project. Although there is already written a lot on the German Uranium Project – and the best overview up to now supplies Mark Walker with his book German National Socialism and the quest for nuclear power, which was published in * Paper presented on a conference in Moscow (November 13/14, 2001) at the Institute for the History of Science and Technology [àÌÒÚËÚÛÚ ËÒÚÓËË ÂÒÚÂÒÚ‚ÓÁ̇ÌËfl Ë ÚÂıÌËÍË ËÏ. -

Heisenberg and the Nazi Atomic Bomb Project, 1939-1945: a Study in German Culture

Heisenberg and the Nazi Atomic Bomb Project http://content.cdlib.org/xtf/view?docId=ft838nb56t&chunk.id=0&doc.v... Preferred Citation: Rose, Paul Lawrence. Heisenberg and the Nazi Atomic Bomb Project, 1939-1945: A Study in German Culture. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1998 1998. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft838nb56t/ Heisenberg and the Nazi Atomic Bomb Project A Study in German Culture Paul Lawrence Rose UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS Berkeley · Los Angeles · Oxford © 1998 The Regents of the University of California In affectionate memory of Brian Dalton (1924–1996), Scholar, gentleman, leader, friend And in honor of my father's 80th birthday Preferred Citation: Rose, Paul Lawrence. Heisenberg and the Nazi Atomic Bomb Project, 1939-1945: A Study in German Culture. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1998 1998. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft838nb56t/ In affectionate memory of Brian Dalton (1924–1996), Scholar, gentleman, leader, friend And in honor of my father's 80th birthday ― ix ― ACKNOWLEDGMENTS For hospitality during various phases of work on this book I am grateful to Aryeh Dvoretzky, Director of the Institute of Advanced Studies of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, whose invitation there allowed me to begin work on the book while on sabbatical leave from James Cook University of North Queensland, Australia, in 1983; and to those colleagues whose good offices made it possible for me to resume research on the subject while a visiting professor at York University and the University of Toronto, Canada, in 1990–92. Grants from the College of the Liberal Arts and the Institute for the Arts and Humanistic Studies of The Pennsylvania State University enabled me to complete the research and writing of the book. -

A Transgender Journey in Three Acts a PROJECT SUBMITTED to THE

Changes in Time: A Transgender Journey in Three Acts A PROJECT SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Ethan Bryce Boatner IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF LIBERAL STUDIES MAY 2012 © Ethan Bryce Boatner 2012 i For Carl and Garé, Josephine B, Jimmy, Timothy, Charles, Greg, Jan – and all the rest of you – for your confidence and unstinting support, from both EBBs. ii BAH! Kid talk! No man is poor who can to what he likes to do once in a while! Scrooge McDuck ~ Only a Poor Old Man iii CONTENTS Chapter By Way of Introduction: On Being and Becoming ..…………………………………………1 1 – There Have Always Been Transgenders–Haven’t There? …………………………….8 2 – The Nosology of Transgenderism, or, What’s Up, Doc? …….………...………….….17 3 – And the Word Was Transgender: Trans in Print, Film, Theatre ………………….….26 4 – The Child Is Father to the Man: Life As Realization ………….…………...……....….32 5 – Smell of the Greasepaint, Roar of the Crowd ……………………………...…….……43 6 – Curtain Call …………………………………………………………………....………… 49 7 – Program ..………………………..……………………………….……………...………..54 8 – Changes in Time ....………………………..…………………….………..….……........59 Wishes ……………………………….………………….……………...…………………60 Dresses …………………………………………………….…………………….….…….85 Changes ………………………………………………………….….………..…………107 9 – Works Cited …………………….………………………………………....…………….131 1 By Way of Introduction On Being and Becoming “I think you’re very brave,” said G as the date for my public play-reading approached. “Why?” I asked. “It takes guts to come out like that, putting all your personal things out in front of everybody,” he replied. “Oh no,” I assured him. “The first six decades took guts–this is a piece of cake.” In fact, I had not embarked on the University of Minnesota’s Master of Liberal Studies (MLS) program with the intention of writing plays. -

Queer Movements in Germany Since Stonewall

LOVE Queer Movements in Germany since AT Stonewall FIRST FIGHT! 1 Queer Movements in LOVE AT Germany since Stonewall FIRST FIGHT! In the night of June 27 to 28, 1969, queer peo- ple militantly resisted a police raid on the Sto- Lesbian feminists vigo- newall Inn bar. For many LGBTQIA communities rously supported the around the world, the days of the uprising feminist cause and pushed against the around Christopher Street in New York mark abortion ban – here at a the beginning of the queer revolt. As a joint demonstration in West project of the Goethe-Institut, Schwules Berlin. Museum Berlin, and the Federal Agency for Civic Edu- cation, this exhibition takes the 50th anniver- sary of the Stonewall Riots as an opportunity to offer an insight into the history of the queer movements in the Federal Republic of Ger- many, the German Democratic Republic, and reunited In the summer of 2019, the exhibition Germany since the 1960s. Particular emphasis is placed on the manifold will tour the Goethe-Instituts in Canada, relations with US movements. the United States, and Mexico, and The exhibition highlights moments of the queer movement’s history without will also be presented at Schwules claiming to tell the only possible story. In doing so, it questions the power dynamic that is at work in the queer poli- Museum Berlin; beginning in 2020, it tics of memory, too, as the debate about the legacy of the Stonewall Riots shows. What is under fire today is the appropriation will travel to other cities worldwide. of the riots by those parts of the movement that, in their struggle for social acceptance, lost sight of the radical goals of the riots and of the cause of many of its heroes: dykes, drag queens, trans people, sex workers, and young people living in precarious conditions, among them many queer people of color. -

Mechanic Street Historic District

Figure 6.2-2. High Style Italianate, 306 North Van Buren Street Figure 6.2-3. Italianate House, 1201 Center Avenue Figure 6.2-4. Italianate House, 615 North Grant Street Figure 6.2-5. Italianate House, 901 Fifth Street Figure 6.2-6. Italianate House, 1415 Fifth Street Figure 6.2-7. High Style Queen Anne House, 1817 Center Avenue Figure 6.2-8. High Style Queen Anne House, 1315 McKinley Avenue featuring an irregular roof form and slightly off-center two-story tower with conical roof on the front elevation. The single-story porch has an off-center entry accented with a shallow pediment. Eastlake details like spindles, a turned balustrade, and turned posts adorn the porch, which extends across the full front elevation and wraps around one corner. The house at 1315 McKinley Avenue also displays a wraparound porch, spindle detailing, steep roof, fish scale wall shingles, and cut-away bay on the front elevation. An umbrage porch on the second floor and multi-level gables on the primary façade add to the asymmetrical character of the house. More typical examples of Queen Anne houses in the district display a variety of these stylistic features. Examples of more common Queen Anne residences in Bay City include 1214 Fifth Street, 600 North Monroe Street, and 1516 Sixth Street (Figures 6.2-9, 6.2-10, and 6.2-11). In general, these buildings have irregular footprints and roof forms. Hipped roofs with cross-gabled bays are common, as are hip-on-gable or jerkinhead details. Porch styles vary but typically extend across the full or partial length of the front elevation and wrap around the building corner. -

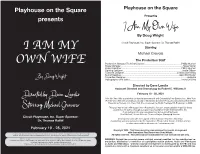

I Am My Own Wife by Doug Wright

Playhouse on the Square Playhouse on the Square Presents presents I Am My Own Wife By Doug Wright Circuit Playhouse, Inc. Super Sponsor: Dr. Thomas Ratliff I AM MY Starring Michael Gravois The Production Staff Production Manager/Technical Director...........................................................Phillip Hughen OWN WIFE Stage Manager...................................................................................................Tessa Verner Scenic Designer...............................................................................................Phillip Hughen Lighting Designer..............................................................................................Justin Gibson Costume Designer....................................................................................Lindsay Schmeling Sound Designer...........................................................................................Jason Eschhofen By Doug Wright Properties Designer.................................................................................................Jinqiu He Videographer and Editor.................................................................................Pedro De Silva Directed by Dave Landis Assistant Directed and Dramaturgy by Robert E. Williams II February 19 - 28, 2021 Directed by Dave Landis I Am My Own Wife is presented by special arrangement with Dramatists Play Service, Inc., New York I Am My Own Wife was originally produced on Broadway by Delphi Productions and David Richenthal. Playwrights Horizon, Inc., New -

Mahlsdorf, Charlotte Von (1928-2002) by Claude J

Mahlsdorf, Charlotte von (1928-2002) by Claude J. Summers Encyclopedia Copyright © 2015, glbtq, Inc. Entry Copyright © 2006 glbtq, Inc. Reprinted from http://www.glbtq.com The cover of the Cleis The fascinating life of preservationist and museum founder Charlotte von Mahlsdorf Press edition of Charlotte von Mahlsdorf's has been the subject of an acclaimed autobiography, a film in which she played autobiography, I Am My herself, and a Pulitzer Prize- and Tony Award-winning play. Own Wife. Courtesy Cleis Press. A controversial figure who may have willingly supplied information to the East German secret police during the period of the German Democratic Republic, Mahlsdorf was nevertheless honored by the German government after reunification for her preservationist and museum work. She was admired by many for her bravery in the face of persecution and for her openness as a transgender public figure during perilous times. Mahlsdorf was born Lothar Berfelde on March 18, 1928 in Berlin. Biologically a male, even as a child she identified as a girl, displayed a fascination with girls' clothing and "old stuff," and preferred to play with "junk" rather than toys. These early interests presaged Lothar Berfelde's later emergence as Charlotte von Mahlsdorf, famous transvestite and collector of everyday historical objects. Preferring the term "transvestite" to "transsexual" since she felt no aversion to her male genitals, Mahlsdorf declared that "In my soul, I feel like a woman" and described her childish self as "a girl in a boy's body." Mahlsdorf's father, Max Berfelde, was a violent man who rose in the ranks of the Nazi party to become party leader in the Mahlsdorf area of Berlin. -

LAWRENCE LIVERMORE LABORATORY University of California/Livermore

yy^ &»* UCRL-5136 RESULTS OF THE 1972 SURVEY ON TRACK REGISTRATION B. V. Griffith March 15, 1973 Prepared for US. Atomic Energy Commission under contract No.W-7405-Eng-48 LAWRENCE LIVERMORE LABORATORY University of California/Livermore v BISTRIBUTI.ON OF THIS DOCUMENT !S" UNLIMITED, NOTICE "This report was prepared as an account of worfe sponsored by iiie United Stales Government. Neither the United Stales nor *he United States Atomic Energy Commission, nor any of their employees, nor any of their contractors, subcontractors, ortheir employees, makes any warranty, express or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product or process disclosed, or represents that its use would not infringe privately- owned rights." Printed in the United States of America Available from National Technical Information Service U. S. Department of Commerce 5285 Port Royal Road Springfield, Virginia 22151 Price: Printed Copy $ *; Microfiche $0.95 * NT1S Pages Selling Price 1-50 $4.00 51-150 $5.45 151-325 $7.60 326-500 $10.60 501-1000 $13.60 TID-4500, UC-41 Health and Safety m LAWRENCE UVERMORE LABORATORY University ot Cetilomia/UvMnore, CaXtomia/S4550 UCRL-51362 RESULTS OF THE ?972 SURVEY ON TRACK REGISTRATION R. V. Griffith MS. date: March 15, 1973 -NOTICE- Thls report was prepared as an account of work sponsored by the United States Government. Neither the United States nor the United States Atomic Energy Commission, nor any of their employees, nor any of their contractors, subcontractors, or their employees, makes any warranty, express or Implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, com pleteness or usefulness of any Information, apparatus, product or process disclosed, or represents that Its use would not infringe privately owned rights. -

The Queer Ecology of I Am My Own Wife

Museum, Furniture, Men: The Queer Ecology of I Am My Own Wife McTighe, P. (2017). Museum, Furniture, Men: The Queer Ecology of I Am My Own Wife. Modern Drama, 150- 168. Published in: Modern Drama Document Version: Peer reviewed version Queen's University Belfast - Research Portal: Link to publication record in Queen's University Belfast Research Portal Publisher rights © 2019 University of Toronto. This work is made available online in accordance with the publisher’s policies. Please refer to any applicable terms of use of the publisher. General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Queen's University Belfast Research Portal is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The Research Portal is Queen's institutional repository that provides access to Queen's research output. Every effort has been made to ensure that content in the Research Portal does not infringe any person's rights, or applicable UK laws. If you discover content in the Research Portal that you believe breaches copyright or violates any law, please contact [email protected]. Download date:01. Oct. 2021 Journal: MD; Volume 60; Issue: 2 DOI: 10.3138/MD.3053 Museum, Furniture, Men: The Queer Ecology of I Am My Own Wife Trish McTighe Abstract: Doug Wright’s I Am My Own Wife attempts to stage the life of a unique trans woman, Charlotte von Mahlsdorf, who lived through Nazi-occupation and Communist- era Berlin, during which time she built and maintained a beloved collection of antiques.