Hetukar Jha Memorial Lecture – 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Emergence of the Mahajanapadas

The Emergence of the Mahajanapadas Sanjay Sharma Introduction In the post-Vedic period, the centre of activity shifted from the upper Ganga valley or madhyadesha to middle and lower Ganga valleys known in the contemporary Buddhist texts as majjhimadesha. Painted grey ware pottery gave way to a richer and shinier northern black polished ware which signified new trends in commercial activities and rising levels of prosperity. Imprtant features of the period between c. 600 and 321 BC include, inter-alia, rise of ‘heterodox belief systems’ resulting in an intellectual revolution, expansion of trade and commerce leading to the emergence of urban life mainly in the region of Ganga valley and evolution of vast territorial states called the mahajanapadas from the smaller ones of the later Vedic period which, as we have seen, were known as the janapadas. Increased surplus production resulted in the expansion of trading activities on one hand and an increase in the amount of taxes for the ruler on the other. The latter helped in the evolution of large territorial states and increased commercial activity facilitated the growth of cities and towns along with the evolution of money economy. The ruling and the priestly elites cornered most of the agricultural surplus produced by the vaishyas and the shudras (as labourers). The varna system became more consolidated and perpetual. It was in this background that the two great belief systems, Jainism and Buddhism, emerged. They posed serious challenge to the Brahmanical socio-religious philosophy. These belief systems had a primary aim to liberate the lower classes from the fetters of orthodox Brahmanism. -

In the Name of Krishna: the Cultural Landscape of a North Indian Pilgrimage Town

In the Name of Krishna: The Cultural Landscape of a North Indian Pilgrimage Town A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Sugata Ray IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Frederick M. Asher, Advisor April 2012 © Sugata Ray 2012 Acknowledgements They say writing a dissertation is a lonely and arduous task. But, I am fortunate to have found friends, colleagues, and mentors who have inspired me to make this laborious task far from arduous. It was Frederick M. Asher, my advisor, who inspired me to turn to places where art historians do not usually venture. The temple city of Khajuraho is not just the exquisite 11th-century temples at the site. Rather, the 11th-century temples are part of a larger visuality that extends to contemporary civic monuments in the city center, Rick suggested in the first class that I took with him. I learnt to move across time and space. To understand modern Vrindavan, one would have to look at its Mughal past; to understand temple architecture, one would have to look for rebellions in the colonial archive. Catherine B. Asher gave me the gift of the Mughal world – a world that I only barely knew before I met her. Today, I speak of the Islamicate world of colonial Vrindavan. Cathy walked me through Mughal mosques, tombs, and gardens on many cold wintry days in Minneapolis and on a hot summer day in Sasaram, Bihar. The Islamicate Krishna in my dissertation thus came into being. -

Colonial Indian Architecture:A Historical Overview

Journal of Xi'an University of Architecture & Technology Issn No : 1006-7930 Colonial Indian Architecture:A Historical Overview Debobrat Doley Research Scholar, Dept of History Dibrugarh University Abstract: The British era is a part of the subcontinent’s long history and their influence is and will be seen on many societal, cultural and structural aspects. India as a nation has always been warmly and enthusiastically acceptable of other cultures and ideas and this is also another reason why many changes and features during the colonial rule have not been discarded or shunned away on the pretense of false pride or nationalism. As with the Mughals, under European colonial rule, architecture became an emblem of power, designed to endorse the occupying power. Numerous European countries invaded India and created architectural styles reflective of their ancestral and adopted homes. The European colonizers created architecture that symbolized their mission of conquest, dedicated to the state or religion. The British, French, Dutch and the Portuguese were the main European powers that colonized parts of India.So the paper therefore aims to highlight the growth and development Colonial Indian Architecture with historical perspective. Keywords: Architecture, British, Colony, European, Modernism, India etc. INTRODUCTION: India has a long history of being ruled by different empires, however, the British rule stands out for more than one reason. The British governed over the subcontinent for more than three hundred years. Their rule eventually ended with the Indian Independence in 1947, but the impact that the British Raj left over the country is in many ways still hard to shake off. -

Gender, Class, Self-Fashioning, and Affinal Solidarity in Modern South Asia

Bucknell University Bucknell Digital Commons Faculty Journal Articles Faculty Scholarship 2009 Im/possible Lives: Gender, Class, Self-Fashioning, and Affinal Solidarity in Modern South Asia Coralynn V. Davis Bucknell University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bucknell.edu/fac_journ Part of the Asian Studies Commons, Human Geography Commons, Race, Ethnicity and Post-Colonial Studies Commons, Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Davis, Coralynn V.. "Im/possible Lives: Gender, Class, Self-Fashioning, and Affinal Solidarity in Modern South Asia." Social Identities: Journal for the Study of Race, Nation and Culture (2009) : 243-272. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Bucknell Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Journal Articles by an authorized administrator of Bucknell Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Im/possible Lives: Gender, class, self-fashioning, and affinal solidarity in modern South Asia Coralynn V. Davis* Women’s and Gender Studies Program Bucknell University Lewisburg, Pennsylvania USA Abstract Drawing on ethnographic research and employing a micro-historical approach that recognizes not only the transnational but also the culturally specific manifestations of modernity, this article centers on the efforts of a young woman to negotiate shifting and conflicting discourses about what a good life might consist of for a highly educated and high caste Hindu woman living at the margins of a nonetheless globalized world. Newly imaginable worlds in contemporary Mithila, South Asia, structure feeling and action in particularly gendered and classed ways, even as the capacity of individuals to actualize those worlds and the “modern” selves envisioned within them are constrained by both overt and subtle means. -

'Listen, Rama's Wife!': Maithil Women's Perspectives and Practices in the Festival of Sāmā-Cake

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Bucknell University Bucknell University Bucknell Digital Commons Faculty Journal Articles Faculty Scholarship 2005 'Listen, Rama’s Wife!’: Maithil Women’s Perspectives and Practices in the Festival of Sāmā-Cakevā Coralynn V. Davis Bucknell University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bucknell.edu/fac_journ Part of the Asian Studies Commons, Folklore Commons, Other Languages, Societies, and Cultures Commons, Other Religion Commons, Performance Studies Commons, Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons, South and Southeast Asian Languages and Societies Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Davis, Coralynn. 2005. “'Listen, Rama’s Wife!’: Maithil Women’s Perspectives and Practices in the Festival of Sāmā- Cakevā.” Asian Folklore Studies 64(1):1-38. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Bucknell Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Journal Articles by an authorized administrator of Bucknell Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Coralynn Davis Bucknell University Lewisburg, PA “Listen, Rama’s Wife!” Maithil Women’s Perspectives and Practices in the Festival of Sāmā Cakevā Abstract As a female-only festival in a significantly gender-segregated society, sāmā cakevā provides a window into Maithil women’s understandings of their society and the sacred, cultural subjectivities, moral frameworks, and projects of self-construction. The festival reminds us that to read male-female relations under patriarchal social formations as a dichotomy between the empowered and the disempowered ignores the porous boundaries between the two in which negotiations and tradeoffs create a symbiotic reliance. -

Indian Universities

Approved University or university Collage in Sri Lanka Any University or University Collage established in Sri Lanka under the Universities Act, No. 16 of 1978 and which are recognized and approved by the University Grants Commission. (Gazette Date 2009.11.06 & Gazette No.1627) 1. Andhra University – Watair 2. Nagarjuna University - Nagarjuna Nagar 3. Kakatiya University – Warangala 4. Osmania University – Hyderabad 5. S.V.University – Tiriupati 6. NTR University of Health Science, Vijiyawada, Andhra Pradesh 7. Gauhati University – Guwahati 8. Kameshwar Singh Darbhanga Sanakrit university, Darbhanga 9. University of Bihar – Muzzaffarpur 10. Pt.Ravi Shanker Shukla University – Raipur 11. Delhi University 12. Goa University 13. University of Gujarat 14. MS University, Baroda 15. Gujarat Ayurveda University, Jamnagar 16. Kurukshetra University, Kurukeshetra 17. Maharashi Dayanand University, Rohtaak 18. Himachal Pradesh University , Simla 19. University of Kerala 20. University of Calicut, Calicut 21. Mahatma Gandhi University, Kottayam 22. Jivaji Vishwavidyaalaya, Gwaalior 23. Devi Ahiiya Vishwavidyalaya, Indore 24. Awadesh Pratap Singh Vishwavidyalaya, Jaipur 25. Rani Durgawati Durawati Vishwaviyalaya, Jaipur 26. Nagpur University, Nagpur 27. University of Poona, Pune 28. Shivaji University, Kolhapur 29. University of Mumbai, Mumbai 30. Amarawati University, Amarawati 31. North Maharashtra University, Jalgon 32. Bharati Vidyapeeth (Deemed University) – Pune 33. University Mysore, Mysore 34. Bangalore University- Bangalore 35. Karnatak University- Dharwar 36. Mangalore University- Mangalore 37. Gulbarga University – Gulbarga 38. Kuvempu University - Shankarghatta 39. Utkal University, Bhubaneshwar 40. Sambaipur University- Burla, Samalpure 41. Berhampur University – Berhampure 42. Gurnanak Dev University – Amritsar 43. Punjabi University – Patiala 44. Punjab University – Chandigarh 45. Rajasthan University - Jaipur 46. University of Madras – Madras 47. Madurai Kamaraj University- Madurai 48. -

State-Building and the Management of Diversity in India (Thirteenth to Seventeenth Centuries) Corinne Lefèvre

State-building and the Management of Diversity in India (Thirteenth to Seventeenth Centuries) Corinne Lefèvre To cite this version: Corinne Lefèvre. State-building and the Management of Diversity in India (Thirteenth to Sev- enteenth Centuries). Medieval History Journal, SAGE Publications, 2014, 16 (2), pp.425-447. 10.1177/0971945813514907. halshs-01955988 HAL Id: halshs-01955988 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-01955988 Submitted on 7 Jan 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. The Medieval History Journal http://mhj.sagepub.com/ State-building and the Management of Diversity in India (Thirteenth to Seventeenth Centuries) Corinne Lefèvre The Medieval History Journal 2013 16: 425 DOI: 10.1177/0971945813514907 The online version of this article can be found at: http://mhj.sagepub.com/content/16/2/425 Published by: http://www.sagepublications.com Additional services and information for The Medieval History Journal can be found at: Email Alerts: http://mhj.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Subscriptions: http://mhj.sagepub.com/subscriptions -

Component-I (A) – Personal Details

Component-I (A) – Personal details: Component-I (B) – Description of module: Subject Name Indian Culture Paper Name Outlines of Indian History Module Name/Title Mahajanapadas- Rise of Magadha – Nandas – Invasion of Alexander Module Id I C/ OIH/ 08 Pre requisites Early History of India Objectives To study the Political institutions of Ancient India from earliest to 3rd Century BCE. Mahajanapadas , Rise of Magadha under the Haryanka, Sisunaga Dynasties, Nanda Dynasty, Persian Invasions, Alexander’s Invasion of India and its Effects Keywords Janapadas, Magadha, Haryanka, Sisunaga, Nanda, Alexander E-text (Quadrant-I) 1. Sources Political and cultural history of the period from C 600 to 300 BCE is known for the first time by a possibility of comparing evidence from different kinds of literary sources. Buddhist and Jaina texts form an authentic source of the political history of ancient India. The first four books of Sutta pitaka -- the Digha, Majjhima, Samyutta and Anguttara nikayas -- and the entire Vinaya pitaka were composed between the 5th and 3rd centuries BCE. The Sutta nipata also belongs to this period. The Jaina texts Bhagavati sutra and Parisisthaparvan represent the tradition that can be used as historical source material for this period. The Puranas also provide useful information on dynastic history. A comparison of Buddhist, Puranic and Jaina texts on the details of dynastic history reveals more disagreement. This may be due to the fact that they were compiled at different times. Apart from indigenous literary sources, there are number of Greek and Latin narratives of Alexander’s military achievements. They describe the political situation prevailing in northwest on the eve of Alexander’s invasion. -

The Keys to British Success in South Asia COLIN WATTERSON

The Keys to British Success in South Asia COLIN WATTERSON “God is on everyone’s side…and in the last analysis he is on the side with plenty of money and large armies” -Jean Anouilh For a period of a period of over one hundred years, the British directly controlled the subcontinent of India. How did a small island nation come on the Edge of the North Atlantic come to dominate a much larger landmass and population located almost 4000 miles away? Historian Sir John Robert Seeley wrote that the British Empire was acquired in “a fit of absence of mind” to show that the Empire was acquired gradually, piece-by-piece. This will paper will try to examine some of the most important reasons which allowed the British to successfully acquire and hold each “piece” of India. This paper will examine the conditions that were present in India before the British arrived—a crumbling central political power, fierce competition from European rivals, and Mughal neglect towards certain portions of Indian society—were important factors in British control. Economic superiority was an also important control used by the British—this paper will emphasize the way trade agreements made between the British and Indians worked to favor the British. Military force was also an important factor but this paper will show that overwhelming British force was not the reason the British military was successful—Britain’s powerful navy, ability to play Indian factions against one another, and its use of native soldiers were keys to military success. Political Agendas and Indian Historical Approaches The historiography of India has gone through four major phases—three of which have been driven by the prevailing world politics of the time. -

Secondary Indian Culture and Heritage

Culture: An Introduction MODULE - I Understanding Culture Notes 1 CULTURE: AN INTRODUCTION he English word ‘Culture’ is derived from the Latin term ‘cult or cultus’ meaning tilling, or cultivating or refining and worship. In sum it means cultivating and refining Ta thing to such an extent that its end product evokes our admiration and respect. This is practically the same as ‘Sanskriti’ of the Sanskrit language. The term ‘Sanskriti’ has been derived from the root ‘Kri (to do) of Sanskrit language. Three words came from this root ‘Kri; prakriti’ (basic matter or condition), ‘Sanskriti’ (refined matter or condition) and ‘vikriti’ (modified or decayed matter or condition) when ‘prakriti’ or a raw material is refined it becomes ‘Sanskriti’ and when broken or damaged it becomes ‘vikriti’. OBJECTIVES After studying this lesson you will be able to: understand the concept and meaning of culture; establish the relationship between culture and civilization; Establish the link between culture and heritage; discuss the role and impact of culture in human life. 1.1 CONCEPT OF CULTURE Culture is a way of life. The food you eat, the clothes you wear, the language you speak in and the God you worship all are aspects of culture. In very simple terms, we can say that culture is the embodiment of the way in which we think and do things. It is also the things Indian Culture and Heritage Secondary Course 1 MODULE - I Culture: An Introduction Understanding Culture that we have inherited as members of society. All the achievements of human beings as members of social groups can be called culture. -

A Comparative Study of Zamindari, Raiyatwari and Mahalwari Land Revenue Settlements: the Colonial Mechanisms of Surplus Extraction in 19Th Century British India

IOSR Journal of Humanities and Social Science (JHSS) ISSN: 2279-0837, ISBN: 2279-0845. Volume 2, Issue 4 (Sep-Oct. 2012), PP 16-26 www.iosrjournals.org A Comparative Study of Zamindari, Raiyatwari and Mahalwari Land Revenue Settlements: The Colonial Mechanisms of Surplus Extraction in 19th Century British India Dr. Md Hamid Husain Guest Faculty, Zakir Husain Delhi College, University of Delhi, India Firoj High Sarwar Research Scholar, Department of History (CAS), AMU, Aligarh, India Abstract: As a colonial mechanism of exploitation the British under East India Company invented and experimented different land revenue settlements in colonized India. Historically, this becomes a major issue of discussion among the scholars in the context of exploitation versus progressive mission in British India. Here, in this paper an attempt has been made to analyze and to interpret the prototype, methods, magnitudes, and far- reaching effects of the three major (Zamindari, Raiytwari and Mahalwari) land revenue settlements in a comparative way. And eventually this paper has tried to show the cause-effects relationship of different modes of revenue assessments, which in turn, how it facilitated Englishmen to provide huge economic vertebrae to the Imperial Home Country, and how it succors in altering Indian traditional society and economic set up. Keywords: Diwani (revenue collection right), Mahal (estate), Potta (lease), Raiyat (peasant), Zamindar (land lord) I. Introduction As agriculture has been the most important economic activity of the Indian people for many centuries and it is the main source of income. Naturally, land revenue management and administration needs a proper care to handle because it was the most important source of income for the state too. -

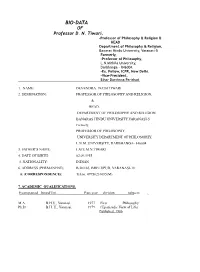

BIO-DATA of Professor D

BIO-DATA OF Professor D. N. Tiwari, -Professor of Philosophy & Religion & HEAD Department of Philosophy & Religion, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi-5 Formerly, -Professor of Philosophy, L.N.Mithila University, Darbhanga – 846004. -Ex. Fellow, ICPR, New Delhi, -Vice-President, Bihar Darshana Parishad. 1. NAME: DEVENDRA NATH TIWARI 2. DESIGNATION: PROFESSOR OF PHILOSOPHY AND RELIGION, & HEAD, DEPARTMENT OF PHILOSOPHY AND RELIGION, BANARAS HINDU UNIVERSITY,VARANASI-5 Formerly, PROFESSOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENT OF PHILOSOPHY, L.N.M. UNIVERSITY, DARBHANGA- 846004 3. FATHER’S NAME: LATE M.N.TIWARI 4. DATE OF BIRTH: 02.09.1955. 5. NATIONALITY: INDIAN 6. ADDRESS (PERMANENT): B.20/185, BHELUPUR, VARANASI-10 & (CORRESPONDENCE): Tel.no. 09956231085(M) 7. ACADEMIC QUALIFICATIONS. Exam.passed board/Uni. Pass year division subjects . M.A. B.H.U., Varanasi. 1977 First Philosophy. Ph.D B.H. U., Varanasi. 1979 (Upanisadic View of Life) Published, 1986 8. (a). Ph. D RESEARCHES PRODUCED UNDER MY SUPERVISION:- 6 Scholars Completed Research for the award of Ph.D. Degree Under my Supervision: Sr. Names Subject Year 1. Smt. Ira Saha Yoga Darsana mein Citta evam Citta ki Vrttiyan: 1990 Eka Adhyayana. 2. Smt.Kiran Kumari, Pracina Bharatiya Darsanon mein Nyayabhasa: 1991. Eka Samiksatmaka Adhyayana. 3. D.N.Jha Pracina Bharatiya Darsanon mein Vakya 1994. Evam Vakyartha Vicara. 4. Ranjit Kumar, Sankara Vedanta evam Kasmira Saiva darsana 1995 Mein Paramatattva ki Awadharana. 5. Hiranath Mishra, Tattvopaplavasinhah: Eka Adhyayana 2004 6. Umeshwar Yadav Ethico-Religious thoughts of Radhakrishnan and Aurobindo: A critical Study(submitted) 2008 (b). Ph. D RESEARCHES ON GOING- 7 9. EMPLOYMENT: Employers date of joining/ Designation Pay Scale Reason for Leaving leaving 1.