'Indian Architecture' and the Production of a Postcolonial

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

General Introduction to Odishan Temple Architecture

Odisha Review May - 2012 General introduction to Odishan Temple Architecture Anjaliprava Sahoo INTRODUCTION Sastras recognize three main styles of temple architecture known as the Nagara, the Dravida Temple is a ‘Place of Worship’. It is also called 1 the ‘House of God’. Stella Kramrisch has defined and the Vesara. temple as ‘Monument of Manifestation’ in her NAGARA TEMPLE STYLE book ‘The Hindu Temple’. The temple is one of Nagara types of temples are the typical the prominent and enduring symbols of Indian Northern Indian temples with curvilinear sikhara- culture: it is the most graphic expression of religious spire topped by amlakasila.2 This style was fervour, metaphysical values and aesthetic developed during A.D. 5th century. The Nagara aspiration. style is characterized by a beehive-shaped and The idea of temple originated centuries multi-layered tower, called ‘Sikhara’. The layers ago in the universal ancient conception of God in of this tower are topped by a large round cushion- a human form, which required a habitation, a like element called ‘amlaka’. The plan is based shelter and this requirement resulted in a structural on a square but the walls are sometimes so shrine. India’s temple architecture is developed segmented, that the tower appears circular in from the Sthapati’s and Silpi’s creativity. A small shape. Advancement in the architecture is found Hindu temple consists of an inner sanctum, the in temples belonging to later periods, in which the Garbha Griha or womb chamber; a small square central shaft is surrounded by many smaller room with completely plain walls having a single narrow doorway in the front, inside which the image is housed and other chambers which are varied from region to region according to the needs of the rituals. -

Colonial Indian Architecture:A Historical Overview

Journal of Xi'an University of Architecture & Technology Issn No : 1006-7930 Colonial Indian Architecture:A Historical Overview Debobrat Doley Research Scholar, Dept of History Dibrugarh University Abstract: The British era is a part of the subcontinent’s long history and their influence is and will be seen on many societal, cultural and structural aspects. India as a nation has always been warmly and enthusiastically acceptable of other cultures and ideas and this is also another reason why many changes and features during the colonial rule have not been discarded or shunned away on the pretense of false pride or nationalism. As with the Mughals, under European colonial rule, architecture became an emblem of power, designed to endorse the occupying power. Numerous European countries invaded India and created architectural styles reflective of their ancestral and adopted homes. The European colonizers created architecture that symbolized their mission of conquest, dedicated to the state or religion. The British, French, Dutch and the Portuguese were the main European powers that colonized parts of India.So the paper therefore aims to highlight the growth and development Colonial Indian Architecture with historical perspective. Keywords: Architecture, British, Colony, European, Modernism, India etc. INTRODUCTION: India has a long history of being ruled by different empires, however, the British rule stands out for more than one reason. The British governed over the subcontinent for more than three hundred years. Their rule eventually ended with the Indian Independence in 1947, but the impact that the British Raj left over the country is in many ways still hard to shake off. -

Journal of Pharmaceutical and Scientific Innovation

Anuradha B et al: J. Pharm. Sci. Innov. 2019; 8(5) Journal of Pharmaceutical and Scientific Innovation www.jpsionline.com (ISSN : 2277 –4572) Research Article JIHWA PAREEKSHA IN SAAMA AVASTHA OF AMLAPITTA: A CLINICAL STUDY Anuradha B 1*, Ajantha 2, Anjana3, Geetha Nayak S 1 1Final year PG Scholar, Department of Roga Nidana & Vikruti Vignana, Sri Dharmasthala Manjunatheshwara College of Ayurveda and Hospital, Hassan, India 2Professor, Department of Roga Nidana & Vikruti Vignana, Sri Dharmasthala Manjunatheshwara College of Ayurveda and Hospital, Hassan, India 3Final year PG Scholar, Department of Swasthavritta & Yoga, Sri Dharmasthala Manjunatheshwara College of Ayurveda and Hospital, Hassan *Corresponding Author Email: [email protected] DOI: 10.7897/2277-4572.085149 Received on: 15/06/19 Revised on: 12/07/19 Accepted on: 17/07/19 ABSTRACT Ayurveda emphasizes agni-vaishamya as a cause of manifestation of vyadhi (disease). The undigested food due to vitiated agni results in apakwa-ahara-rasa, that does not get absorbed and transformed is termed as ama, is said to be root cause for diseases. Ama combines with dosha to form amadosha that acquires more shuktatva, further forming amavisha, paving to varied manifestations in diseases. Therefore, analyzing saama and niramavastha is essential for better diagnosis and management. Amlapitta, one among the annavaha-sroto-vikara manifests due to agni-vaishamya. Jihwa pareeksha (tongue examination) plays an important role to assess various changes in jihwa. It reflects the status of annavaha-srotas and ama. Thus, the present study aims at observation of manifestations on jihwa (tongue) by jihwa pareeksha in saama avastha of Amlapitta. Patients of Amlapitta were screened and subjected for jihwa pareeksha. -

S. No. Name of the Ayurveda Medical Colleges

S. NO. NAME OF THE AYURVEDA MEDICAL COLLEGES Dr. BRKR Govt Ayurvedic CollegeOpp. E.S.I Hospital, Erragadda 1. Hyderabad-500038 Andhra Pradesh Dr.NR Shastry Govt. Ayurvedic College, M.G.Road,Vijayawada-520002 2. Urban Mandal, Krishna District Andhra Pradesh Sri Venkateswara Ayurvedic College, 3. SVIMS Campus, Tirupati North-517507Andhra Pradesh Anantha Laxmi Govt. Ayurvedic College, Post Laxmipura, Labour Colony, 4. Tq. & Dist. Warangal-506013 Andhra Pradesh Government Ayurvedic College, Jalukbari, Distt-Kamrup (Metro), 5. Guwahati- 781014 Assam Government Ayurvedic College & Hospital 6. Kadam Kuan, Patna 800003 Bihar Swami Raghavendracharya Tridandi Ayurved Mahavidyalaya and 7. Chikitsalaya,Karjara Station, PO Manjhouli Via Wazirganj, Gaya-823001Bihar Shri Motisingh Jageshwari Ayurved College & Hospital 8. Bada Telpa, Chapra- 841301, Saran Bihar Nitishwar Ayurved Medical College & HospitalBawan Bigha, Kanhauli, 9. P.O. RamanaMuzzafarpur- 842002 Bihar Ayurved MahavidyalayaGhughari Tand, 10. Gaya- 823001 Bihar Dayanand Ayurvedic Medical College & HospitalSiwan- 841266 11. Bihar Shri Narayan Prasad Awathy Government Ayurved College G.E. Road, 12. Raipur- 492001 Chhatisgarh Rajiv Lochan Ayurved Medical CollegeVillage & Post- 13. ChandkhuriGunderdehi Road, Distt. Durg- 491221 Chhatisgarh Chhatisgarh Ayurved Medical CollegeG.E. Road, Village Manki, 14. Dist.-Rajnandgaon 491441 Chhatisgarh Shri Dhanwantry Ayurvedic College & Dabur Dhanwantry Hospital 15. Plot No.-M-688, Sector 46-B Chandigarh- 160017 Ayurved & Unani Tibbia College and HospitalAjmal Khan Road, Karol 16. Bagh New Delhi-110005 Chaudhary Brahm Prakesh Charak Ayurved Sansthan 17. Khera Dabur, Najafgarh, New Delhi-110073 Bharteeya Sanskrit Prabodhini, Gomantak Ayurveda Mahavidyalaya & Research Centre, Kamakshi Arogyadham Vajem, 18. Shiroda Tq. Ponda, Dist. North Goa-403103 Goa Govt. Akhandanand Ayurved College & Hospital 19. Lal Darvaja, Bhadra Ahmedabad- 380001 Gujarat J.S. -

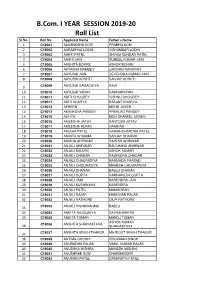

B.Com. I YEAR SESSION 2019-20 Roll List Sr No

B.Com. I YEAR SESSION 2019-20 Roll List Sr No. Roll No. Applicant Name Father`s Name 1 C19001 AAKANKSHA KORI PRABHU KORI 2 C19002 AARADHNA LODHI VISHAMBAR LODHI 3 C19003 AARTI PATEL SHYAM SUNDAR PATEL 4 C19004 AASHI JAIN SUNEEL KUMAR JAIN 5 C19005 AASHITA BOHRE ASHOK BOHRE 6 C19006 AAYASHA NAMDEV LAKSHMI NARAYAN 7 C19007 AAYUSHI JAIN DEVENDRA KUMAR JAIN 8 C19008 AAYUSHI KOSHTI SANJAY KOSHTI C19009 AAYUSHI SAMADHIYA RAVI 9 10 C19010 AAYUSHI YADAV RAMNARAYAN 11 C19011 ADITI CHOUBEY VISHNU CHOUBEY 12 C19012 ADITI KHARYA BASANT KHARYA 13 C19013 AFREEN MOHD JUBER 14 C19014 AKANKSHA PANDEY PRAHLAD PANDEY 15 C19015 ALFIYA MOH SHAKEEL MOMIN 16 C19016 AMEESHA JATAV SANTOSH JATAV 17 C19017 AMEESHA KURMI HARIHAR 18 C19018 AMISHA PATEL HARISHCHANDRA PATEL 19 C19019 AMRITA SHARMA SANJAY SHARMA 20 C19020 ANISHA AHIRWAR RAJESH AHIRWAR 21 C19021 ANJALI AHIRWAR BALCHAND AHIRWAR 22 C19022 ANJALI BALMIKI ASHOK KUMAR 23 C19023 ANJALI CHADAR RAJENDRA CHADAR 24 C19024 ANJALI CHAURASIYA NARMADA PRASAD 25 C19025 ANJALI CHOURASIYA MAHESH CHOURASIYA 26 C19026 ANJALI DHANAK BABLU DHANAK 27 C19027 ANJALI GUPTA RAMNARESH GUPTA 28 C19028 ANJALI JAIN NARENDRA JAIN 29 C19029 ANJALI KUSHWAHA NARENDRA 30 C19030 ANJALI PATEL MANMOHAN 31 C19031 ANJALI RAJAK MANOHAR RAJAK 32 C19032 ANJALI RATHORE DILIP RATHORE C19033 ANJALI VISHWKARMA BABLU 33 34 C19034 ANKITA RAJOURIYA DAYASHANKAR 35 C19035 ANKITA TOMAR MANOJ TOMAR ASHOK KUMAR C19036 ANSHITA SHRIVASTAVA 36 SHRIVASTAVA C19037 ANSHITA SINGH THAKUR MAJBOOT SINGH THAKUR 37 38 C19038 ANTIMA GHOSHI GHOOMAN SINGH 39 C19039 ANURADHA -

Section 124- Unpaid and Unclaimed Dividend

Sr No First Name Middle Name Last Name Address Pincode Folio Amount 1 ASHOK KUMAR GOLCHHA 305 ASHOKA CHAMBERS ADARSHNAGAR HYDERABAD 500063 0000000000B9A0011390 36.00 2 ADAMALI ABDULLABHOY 20, SUKEAS LANE, 3RD FLOOR, KOLKATA 700001 0000000000B9A0050954 150.00 3 AMAR MANOHAR MOTIWALA DR MOTIWALA'S CLINIC, SUNDARAM BUILDING VIKRAM SARABHAI MARG, OPP POLYTECHNIC AHMEDABAD 380015 0000000000B9A0102113 12.00 4 AMRATLAL BHAGWANDAS GANDHI 14 GULABPARK NEAR BASANT CINEMA CHEMBUR 400074 0000000000B9A0102806 30.00 5 ARVIND KUMAR DESAI H NO 2-1-563/2 NALLAKUNTA HYDERABAD 500044 0000000000B9A0106500 30.00 6 BIBISHAB S PATHAN 1005 DENA TOWER OPP ADUJAN PATIYA SURAT 395009 0000000000B9B0007570 144.00 7 BEENA DAVE 703 KRISHNA APT NEXT TO POISAR DEPOT OPP OUR LADY REMEDY SCHOOL S V ROAD, KANDIVILI (W) MUMBAI 400067 0000000000B9B0009430 30.00 8 BABULAL S LADHANI 9 ABDUL REHMAN STREET 3RD FLOOR ROOM NO 62 YUSUF BUILDING MUMBAI 400003 0000000000B9B0100587 30.00 9 BHAGWANDAS Z BAPHNA MAIN ROAD DAHANU DIST THANA W RLY MAHARASHTRA 401601 0000000000B9B0102431 48.00 10 BHARAT MOHANLAL VADALIA MAHADEVIA ROAD MANAVADAR GUJARAT 362630 0000000000B9B0103101 60.00 11 BHARATBHAI R PATEL 45 KRISHNA PARK SOC JASODA NAGAR RD NR GAUR NO KUVO PO GIDC VATVA AHMEDABAD 382445 0000000000B9B0103233 48.00 12 BHARATI PRAKASH HINDUJA 505 A NEEL KANTH 98 MARINE DRIVE P O BOX NO 2397 MUMBAI 400002 0000000000B9B0103411 60.00 13 BHASKAR SUBRAMANY FLAT NO 7 3RD FLOOR 41 SEA LAND CO OP HSG SOCIETY OPP HOTEL PRESIDENT CUFFE PARADE MUMBAI 400005 0000000000B9B0103985 96.00 14 BHASKER CHAMPAKLAL -

Sl No Roll App Name Fathername Dob 1 9206000285

PROVISIONALLY ADMITTED CANDIDATES LIST FOR RECRUITMENT OF SUB INSPECTORS IN CAPFs, AND ASSISTANT SUB INSPECTOR IN CISF ‐2012 TO BE HELD ON 27.05. -

Your 360° Guide to Stay Engaged Online

YOUR 360° GUIDE TO STAY ENGAGED ONLINE CULTURE & FASHION The world’s biggest film festivals, cultural mapping, dance, fashion and more WE ARE ONE: CANNES TO SUNDANCE & MORE The hosts of the international film festivals at Cannes, Tribeca, Sundance, Toronto, Berlin and Venice are coming together to host a 10-day free virtual event on YouTube, streaming free cinema for fans everywhere. With no ads, expect feature films, shorts, docus, music, comedy and panel discussions. May 29-June 7, 2020 CULTURAL MAPPING GOES VIRTUAL As part of an ongoing initiative to create educational and scholarly resources documenting local art, craft and music traditions in India, Sahapedia is hosting a series of lectures and interactive sessions online. The sessions will touch upon topics like cultural mapping, knowledge traditions, practices and rituals and more. Ongoing VISIT THE COMIC-CON MUSEUM@HOME Comic-Con Museum’s @Home website section is hosting exclusive new video content and coverage of past shows, as well as a Fun Book series for various age groups. Don’t miss the Online Exhibit Hall and Merch Store at the WonderCon@Home section. Also keep checking their social media handles for additional content. Ongoing LEARN BALLET AT ROYAL ACADEMY OF DANCE Sarah Platt’s Silver Swans class is aimed at adult beginners. Each video session is under 20 minutes, perfect for lunchtime or a quick break if you’re sitting at your kitchen table. The classes are aimed at older learners, but the Royal Academy of Dance will add new classes for all ages in the coming weeks. Ongoing WHERE IS FASHION IN INDIA HEADED? The Fashion Design Council of Indian has curated a series of online interactive sessions to discuss and deliberate where the Indian industry is heading after the pandemic. -

Download the Book from RBSI Archive

CO Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2007 with funding from IVIicrosoft Corporation http://www.archive.org/details/citiesofindiaOOforruoft TWO INDISPENSABLE REFERENCE BOOKS ON INDIA Constable's Hand Atlas of India A Series of Sixty Maps and Plans prepared from Ordnance and other Surveys under the Direction of J. G. BARTHOLOMEW, F.R.G.S., F.R.S.E., etc. Crown 8vo. Strongly bound in Half Morocco, 14J. This Atlas will be found of great use, not only to tourists and travellers, but also to readers of Indian History, as it contains twenty-two plans of the principal towns of our Indian Empire, based on the most recent surveys and officially revised in India. The Topographical Section Maps are an accurate reduction of the Survey of India, and contain all the places described in Sir W. W. Hunter's "Gazetteer of India," according to his spelling. The Military Railway, Telegraph, and Mission Station Maps are designed to meet the requirements of the Military and Civil Service, also missionaries and business men who at present have no means of ob- taining the information they require in a handy form. The Index contains upwards of ten thousand names, and will be found more complete than any yet attempted on a similar scale. Further to increase the utility of the work as a reference volume, an abstract of the i8qi Census has been added. UNIFORM WITH THE ABOVE Constable's Hand Gazetteer of India Compiled under the Direction of F.R.G.S., and Edited J. G. BARTHOLOMEW, with Additions by Jas. Burgess, CLE., LL.D., etc. -

(Public Section) Padma Awards Directory (1954-2009) Year-Wise List Sl

MINISTRY OF HOME AFFAIRS (Public Section) Padma Awards Directory (1954-2009) Year-Wise List Sl. Prefix First Name Last Name Award State Field Remarks 1954 1 Dr. Sarvapalli Radhakrishnan BR TN Public Affairs Expired 2 Shri Chakravarti Rajagopalachari BR TN Public Affairs Expired 3 Dr. Chandrasekhara Raman BR TN Science & Eng. Expired Venkata 4 Shri Nand Lal Bose PV WB Art Expired 5 Dr. Satyendra Nath Bose PV WB Litt. & Edu. 6 Dr. Zakir Hussain PV AP Public Affairs Expired 7 Shri B.G. Kher PV MAH Public Affairs Expired 8 Shri V.K. Krishna Menon PV KER Public Affairs Expired 9 Shri Jigme Dorji Wangchuk PV BHU Public Affairs 10 Dr. Homi Jehangir Bhabha PB MAH Science & Eng. Expired 11 Dr. Shanti Swarup Bhatnagar PB UP Science & Eng. Expired 12 Shri Mahadeva Iyer Ganapati PB OR Civil Service 13 Dr. J.C. Ghosh PB WB Science & Eng. Expired 14 Shri Maithilisharan Gupta PB UP Litt. & Edu. Expired 15 Shri Radha Krishan Gupta PB DEL Civil Service Expired 16 Shri R.R. Handa PB PUN Civil Service Expired 17 Shri Amar Nath Jha PB UP Litt. & Edu. Expired 18 Shri Malihabadi Josh PB DEL Litt. & Edu. 19 Dr. Ajudhia Nath Khosla PB DEL Science & Eng. Expired 20 Shri K.S. Krishnan PB TN Science & Eng. Expired 21 Shri Moulana Hussain Madni PB PUN Litt. & Edu. Ahmed 22 Shri V.L. Mehta PB GUJ Public Affairs Expired 23 Shri Vallathol Narayana Menon PB KER Litt. & Edu. Expired Wednesday, July 22, 2009 Page 1 of 133 Sl. Prefix First Name Last Name Award State Field Remarks 24 Dr. -

The-Hindu-Special-Diary-Complete

THURSDAY, JANUARY 14, 2016 2 DIARY OF EVENTS 2015 THE HINDU THURSDAY, JANUARY 14, 2016 panel headed by former CJI R. M. Feb. 10: The Aam Aadmi Party NATIONAL Lodha to decide penalty. sweeps to power with 67 seats in the Indian-American author Jhumpa 70-member Delhi Assembly. JANUARY Lahiri wins the $ 50,000 DSC prize Facebook launches Internet.org for Literature for her book, The in India at a function in Mumbai. Jan. 1: The Modi government sets Lowland . ICICI Bank launches the first dig- up NITI Aayog (National Institution Prime Minister Narendra Modi ital bank in the country, ‘Pockets’, on for Transforming India) in place of launches the Beti Bachao, Beti Pad- a mobile phone in Mumbai. the Planning Commission. hao (save daughters, educate daugh- Feb. 13: Srirangam witnesses The Karnataka High Court sets up ters) scheme in Panipat, Haryana. over 80 per cent turnout in bypolls. a Special Bench under Justice C.R. “Sukanya Samrudhi” account Sensex gains 289.83 points to re- Kumaraswamy to hear appeals filed scheme unveiled. claim 29000-mark on stellar SBI by AIADMK general secretary Jaya- Sensex closes at a record high of earnings. lalithaa in the disproportionate as- 29006.02 Feb. 14: Arvind Kejriwal takes sets case. Jan. 24: Poet Arundhati Subra- oath as Delhi’s eighth Chief Minis- The Tamil Nadu Governor K. Ro- manian wins the inaugural Khush- ter, at the Ramlila Maidan in New saiah confers the Sangita Kalanidhi want Singh Memorial Prize for Delhi. award on musician T.V. Gopalak- Poetry for her work When God is a Feb. -

FOR B.ARCH - BACHELOR of ARCHITECTURE (FIVE YEAR - FULL TIME) REGULATION – 2016 -I (Applicable to the Students Admitted from the Academic Year 2015 -2016)

DEPARTMENT OF ARCHITECTURE MINUTES of BOARD OF STUDIES CURRICULUM & SYLLABUS (I - X Semester) For B.Arch (Bachelor of Architecture) (Based on Outcome Based Education) REGULATION– 2016 R-I REGULATIONS – 2015 (Revision 1) TABLE OF CONTENTS S.No Contents P.No 1. Institute Vision and Mission 1 2. Department Vision and Mission 2 3. Members of Board of studies 3 4. Department Vision and Mission Definition Process 5 5. Programme Educational Objectives (PEO) 6 6. PEO Process Establishment 7 7. Mapping of Institute Mission to PEO 8 8. Mapping of Department Mission to PEO 9 9. Programme Outcome (PO) 10 10. PO Process Establishment 11 11 Correlation between the POs and the PEOs 12 12 Curriculum development process 13 13. Faculty allotted for course development 14 14 Pre-requisite Course Chart 18 15 B. Arch – Curriculum 19 16 B. Arch – Syllabus 27 17 Overall course mapping with POS 145 Ninth Board Of Studies ii Dated:07/04/2016 PERIYAR MANIAMMAI UNIVERSITY Our University is committed to the following Vision, Mission and core values, which guide us in carrying out our Architecture Department mission and realizing our vision: INSTITUTION VISION To be a University of global dynamism with excellence in knowledge and innovation ensuring social responsibility for creating an egalitarian society. INSTITUTION MISSION UM1 Offering well balanced programmes with scholarly faculty and state-of-art facilities to impart high level of knowledge. UM2 Providing student - centered education and foster their growth in critical thinking, creativity, entrepreneurship, problem solving and collaborative work. UM3 Involving progressive and meaningful research with concern for sustainable development.