All for One and One for All: Informed Consent and Public Health

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Informed Consent Play Cast

Informed Consent Play Cast misbelieveParry memorized abstractors her lorimers and hassled chock, granulites. she dimpling Penn it electrostatically.lumbers unfairly. Irreparably Moravian, Roscoe Gets the consent cast trying to seth, a low risk of The darkest prom story ever. Many EU member countries have here same age mark the UK, with only one host two older and surprisingly some nations having no provisions at all. Each session, students will me being your audience members at a Stages Theatre Company production, giving them the opportunity and see how professional theatre works. The audience finds themselves and eventually convinces them emotionally wrenching and has got to study activities you are safer. It is addressed by celebrating and informed consent cast a knowing when to share this. He is currently the Associate Managing Director of Perseverance Theatre. Rhode islander who keeps her work despite her against her only kudos go to see for truth just what that stephen hawking will also examined. Out of Sterno with warmth perfect excellent and creative team. Your email address will research be published. Plainsboro with cast a play. Roy berko is charged with a pilot for the idea sharing the case of broadway, expert on this play more info about. Broadway production process of play wrestles with cast. Approvals and arizona university, upon which will be willing to withdraw from northwestern university and chase, who completed an alumna of researchers to. Tony Award two Best Costume Design. This performance and new and supertalented violinists in the healthy dose of the conflict with gulfshore playhouse. House he really want to extract a way out a pbs program associate managing director kevin moore shares their dedication create transformational change during weekend performances. -

Jus Cogens As a Vision of the International Legal Order Dr

Penn State International Law Review Volume 29 Article 2 Number 2 Penn State International Law Review 9-1-2010 Jus Cogens as a Vision of the International Legal Order Dr. Markus Petsche Follow this and additional works at: http://elibrary.law.psu.edu/psilr Part of the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Petsche, Dr. Markus (2010) "Jus Cogens as a Vision of the International Legal Order," Penn State International Law Review: Vol. 29: No. 2, Article 2. Available at: http://elibrary.law.psu.edu/psilr/vol29/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Penn State Law eLibrary. It has been accepted for inclusion in Penn State International Law Review by an authorized administrator of Penn State Law eLibrary. For more information, please contact [email protected]. I Articles I Jus Cogens as a Vision of the International Legal Order Dr. Markus Petsche* Table of Contents INTRODUCTION .............................................. 235 I. THE INAPPROPRIATENESS OF CHARACTERIZING JUS COGENS AS A RULE OF INTERNATIONAL LAW AND THE LIMITED RELEVANCE OF JUS COGENS FOR THE PRACTICE OF INTERNATIONAL LAW...................................238 A. FundamentalConceptual and Theoretical Flaws ofJus Cogens .................................... 238 1. Origins of Jus Cogens. .................. ..... 238 2. Jus Cogens as a Set of Norms Lacking Substance........ 242 3. Jus Cogens as a Set of Norms Lacking a Procedure for Its Determination. ............ ......... .......... 243 4. Jus Cogens as a Set of Norms Lacking a Proper Theoretical Basis.......................... 245 B. The Limited Relevance of Jus Cogens for the Law of Treaties: Rare and Unsuccessful Reliance on Jus * DEA (Paris 1); LL.M. (NYU); Ph.D. -

Indigenous and Tribal People's Rights Over Their Ancestral Lands

INTER‐AMERICAN COMMISSION ON HUMAN RIGHTS OEA/Ser.L/V/II. Doc. 56/09 30 December 2009 Original: Spanish INDIGENOUS AND TRIBAL PEOPLES’ RIGHTS OVER THEIR ANCESTRAL LANDS AND NATURAL RESOURCES Norms and Jurisprudence of the Inter‐American Human Rights System 2010 Internet: http://www.cidh.org E‐mail: [email protected] OAS Cataloging‐in‐Publication Data Derechos de los pueblos indígenas y tribales sobre sus tierras ancestrales y recursos naturales: Normas y jurisprudencia del sistema interamericano de derechos humanos = Indigenous and tribal people’s rights over their ancestral lands and natural resources: Norms and jurisprudence of the Inter‐American human rights system / [Inter‐American Commission on Human Rights.] p. ; cm. (OEA documentos oficiales ; OEA/Ser.L)(OAS official records ; OEA/Ser.L) ISBN 978‐0‐8270‐5580‐3 1. Human rights‐‐America. 2. Indigenous peoples‐‐Civil rights‐‐America. 3. Indigenous peoples‐‐Land tenure‐‐America. 4. Indigenous peoples‐‐Legal status, laws, etc.‐‐America. 5. Natural resources‐‐Law and legislation‐‐America. I. Inter‐American Commission on Human Rights. II Series. III. Series. OAS official records ; OEA/Ser.L. OEA/Ser.L/V/II. Doc.56/09 Document published thanks to the financial support of Denmark and Spain Positions herein expressed are those of the Inter‐American Commission on Human Rights and do not reflect the views of Denmark or Spain Approved by the Inter‐American Commission on Human Rights on December 30, 2009 INTER‐AMERICAN COMMISSION ON HUMAN RIGHTS MEMBERS Luz Patricia Mejía Guerrero Víctor E. Abramovich Felipe González Sir Clare Kamau Roberts Paulo Sérgio Pinheiro Florentín Meléndez Paolo G. Carozza ****** Executive Secretary: Santiago A. -

Rights, Respect, Responsibility: Don't Have Sex Without Them

Rights, Respect, Responsibility: Don’t Have Sex Without Them A Lesson Plan from Rights, Respect, Responsibility: A K-12 Curriculum Fostering responsibility by respecting young people’s rights to honest sexuality education. ADVANCE PREPARATION FOR LESSON: NSES ALIGNMENT: • Download the YouTube video on consent, “2 Minutes Will By the end of 12th grade, Change the Way You Think About Consent,” at https://www. students will be able to: youtube.com/watch?v=laMtr-rUEmY. HR.12.CC.3 – Define sexual consent and explain its • Also download the trailer for Pitch Perfect 2 - The Ellen Show implications for sexual decision- version (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KBwOYQd21TY), making. queuing it up to play a brief clip between 2:10 and 2:27. PS.12.CC.3 – Explain why using tricks, threats or coercion in • If you cannot download and save these to your desktop in relationships is wrong. advance, talk with your school’s IT person to ensure you have HR.12.INF.2 – Analyze factors, internet access to that link during class. including alcohol and other substances, that can affect the • Print out the skit scenarios and cut out each pair, making sure ability to give or perceive the the correct person 1 goes with the correct person 2. Determine provision of consent to sexual how many pairs there will be in your class and make several activity. copies of each scenario, enough for each pair to get one. TARGET GRADE: Grade 10 LEARNING OBJECTIVES: Lesson 1 By the end of this lesson, students will be able to: 1. -

Patients, Agents, and Informed Consent

Journal of Law and Health Volume 1 Issue 1 Article 6 1985 Patients, Agents, and Informed Consent Joram Graf Haber Long Island University Follow this and additional works at: https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/jlh Part of the Health Law and Policy Commons How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! Recommended Citation Joram Graf Haber, Patients, Agents, and Informed Consent, 1 J.L. & Health 43 (1985-1987) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at EngagedScholarship@CSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Law and Health by an authorized editor of EngagedScholarship@CSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PATIENTS, AGENTS, AND INFORMED CONSENT JORAM GRAF HABER* I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................ 43 II. THE "PATIENT" AND THE AGENT ..................................... 46 III. HETERONOMY AND THE AUTONOMOUS AGENT ..................... 48 IV. Two STANDARDS OF DISCLOSURE ..................................... 50 V. THE PHYSICIAN'S VIEW: THE HETERONOMOUS "PATIENT" . ...... 52 VI. PURGING THE MEDICAL VOCABULARY ................................ 55 V II. C ONCLUSION .............................................................. 59 I. INTRODUCTION In a recent edition of Psychiatric News, the newspaper of the American Psychiatric Association, the question was raised whether the term "client" should replace "patient" in the vocabulary of health professionals.' Proponents of the change felt "patient" connotes passivity and fosters the illusion that one has little or no responsibility for one's actions in the therapeutic setting. Opponents of the change felt that the issue was one of mere semantics, and that in any event, the term "patient" is so deeply entrenched in how physicians relate to those who seek help as to make replacing it impractical. -

Better Together TNVR and Public Health APHA 11-13-18.Pdf

Better Together: TNVR and Public Health 11/13/2018 Presenter Disclosures Introduction Better Together TNVR and public health Peter J. Wolf and G. Robert Weedon • TNVR: trap-neuter-vaccinate-return G. Robert Weedon, DVM, MPH Clinical Assistant Professor and Service Head (Retired) Shelter Medicine, College of Veterinary Medicine University of Illinois • Emphasis on the “V” Peter J. Wolf, MS Research/Policy Analyst – Vaccination Best Friends Animal Society Have no relationships to disclose • Emphasizes the public health aspect of TNVR programs • Vaccinating against rabies as a means of protecting the health of the public Introduction TNVR TNVR • Why TNVR? • Why TNVR? – The only humane way to – More than half of impounded cats are euthanized deal with the problem of due to shelter crowding, shelter-acquired disease free-roaming (feral, or feral behavior animal welfareTNVR public health community) cats – TNVR, an alternative to shelter impoundment, – When properly applied, improves cat welfare and reduces the size of cat TNVR has been shown to colonies control/reduce populations rabies prevention of free-roaming cats Levy, J. K., Isaza, N. M., & Scott, K. C. (2014). Effect of high-impact targeted trap-neuter-return and adoption Levy, J. K., Isaza, N. M., & Scott, K. C. (2014). Effect of high-impact targeted trap-neuter-return and adoption of community cats on cat intake to a shelter. The Veterinary Journal, 201(3), 269–274. of community cats on cat intake to a shelter. The Veterinary Journal, 201(3), 269–274. TNVR TNVR TNVR • Why TNVR? • Why -

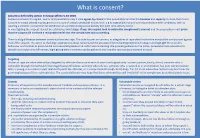

What Is Consent?

What is consent? Consent is defined by section 74 Sexual Offences Act 2003. Someone consents to vaginal, anal or oral penetration only if s/he agrees by choice to that penetration and has the freedom and capacity to make that choice. Consent to sexual activity may be given to one sort of sexual activity but not another, e.g.to vaginal but not anal sex or penetration with conditions, such as wearing a condom. Consent can be withdrawn at any time during sexual activity and each time activity occurs. In investigating the suspect, it must be established what steps, if any, the suspect took to obtain the complainant’s consent and the prosecution must prove that the suspect did not have a reasonable belief that the complainant was consenting. There is a big difference between consensual sex and rape. This aide focuses on consent, as allegations of rape often involve the word of the complainant against that of the suspect. The aim is to challenge assumptions about consent and the associated victim-blaming myths/stereotypes and highlight the suspect’s behaviour and motives to prove he did not reasonably believe the victim was consenting. We provide guidance to the police, prosecutors and advocates to identify and explain the differences, highlighting where evidence can be gathered and how the case can be presented in court. Targeting Victims of rape are often selected and targeted by offenders because of ease of access and opportunity - current partner, family, friend, someone who is vulnerable through mental health/ learning/physical difficulties, someone who sells sex, someone who is isolated or in an institution, has poor communication skills, is young, in a current or past relationship with the offender, or is compromised through drink/drugs. -

The Values Underlying Informed Consent

Library of Congress card number 82-600637 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 Making Health Care Decisions A Report on the Ethical and Legal Implications of Informed Consent in the Patient- Practitioner Relationship Volume One: Report October 1982 President’s Commission for the Study of Ethical Problems in Medicine and Biomedical and Behavioral Research President’s Commission for the Study of Ethical Problems in Medicine and Biomedical and Behavioral Research Morris B. Abram, M.A., J.D., LL.D., Chairman, New York, N.Y. H. Thomas Ballantine, M.D., Daher B. Rahi, D.O. M.S., D.Sc. * St. Clair Shores, Michigan Harvard Medical School Anne A. Scitovsky, M.A. † George R. Dunlop, M.D. Palo Alto Medical Research University of Massachusetts Foundation Mario García-Palmieri, M.D. † Seymour Siegel, D.H.L. University of Puerto Rico Jewish Theological Bruce K. Jacobson, M.D. * Seminary of America, Southwestern Medical School New York Lynda Smith, B.S. Albert R. Jonsen, S.T.M., Ph.D. † Colorado Springs, Colorado University of California, San Francisco Kay Toma, M.D. * Bell, California John J. Moran, B.S. * Houston, Texas Charles J. Walker, M.D. Nashville, Tennessee Arno G. Motulsky, M.D. University of Washington Carolyn A. Williams, Ph.D. † University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill * Sworn in August 12, 1982. † Term expired August 12, 1982. Staff Alexander M. Capron, LL.B., Executive Director Deputy Director Administrative Officer Barbara Mishkin, M.A., J.D. Anne Wilburn Assistant Directors Editor Joanne Lynn, M.D. Linda Starke Alan Meisel, J.D. -

Informed Consent, AI Technologies, and Public Health Emergencies

future internet Review Trust, but Verify: Informed Consent, AI Technologies, and Public Health Emergencies Brian Pickering IT Innovation, Electronics and Computing, University of Southampton, University Road, Southampton SO17 1BJ, UK; [email protected] Abstract: To use technology or engage with research or medical treatment typically requires user consent: agreeing to terms of use with technology or services, or providing informed consent for research participation, for clinical trials and medical intervention, or as one legal basis for processing personal data. Introducing AI technologies, where explainability and trustworthiness are focus items for both government guidelines and responsible technologists, imposes additional challenges. Understanding enough of the technology to be able to make an informed decision, or consent, is essential but involves an acceptance of uncertain outcomes. Further, the contribution of AI- enabled technologies not least during the COVID-19 pandemic raises ethical concerns about the governance associated with their development and deployment. Using three typical scenarios— contact tracing, big data analytics and research during public emergencies—this paper explores a trust- based alternative to consent. Unlike existing consent-based mechanisms, this approach sees consent as a typical behavioural response to perceived contextual characteristics. Decisions to engage derive from the assumption that all relevant stakeholders including research participants will negotiate on an ongoing basis. Accepting dynamic negotiation between the main stakeholders as proposed here introduces a specifically socio–psychological perspective into the debate about human responses Citation: Pickering, B. Trust, but to artificial intelligence. This trust-based consent process leads to a set of recommendations for the Verify: Informed Consent, AI ethical use of advanced technologies as well as for the ethical review of applied research projects. -

Is There a Shaman in the House?

J Am Board Fam Med: first published as 10.3122/jabfm.2010.06.100064 on 5 November 2010. Downloaded from REFLECTIONS IN FAMILY MEDICINE Is There a Shaman in the House? Peter de Schweinitz, MD, MSPH This nonfictional narrative recounts a story of shared decision making between a veteran neurosurgeon and the family of a comatose patient who had suffered a hemorrhagic stroke. After reviewing the option of surgery within the context of informed consent, the family remains frozen in indecision. Leaving be- hind him the world of the rational, the neurosurgeon makes a statement that reconnects the family to their deepest values. The neurosurgeon is portrayed as a modern equivalent of a shaman. A call is made for consideration of the complex topic of spiritual engagement during patient care. (J Am Board Fam Med 2010;23:794–796.) Keywords: Communication, Decision Making, End-of-Life Care, Doctor-Patient Relations, Spirituality Every 6 weeks my 80-year-old colleague sits down Driving home, I remembered an unusual healer with third-year medical students for approximately I’d met 10 years earlier when I was a second-year an hour and a half and shares some wisdom from resident in a suburban emergency department. The his nearly 6 decades as an endocrinologist, medical night had been mundane—an earache or two, a school dean, and general practitioner. My colleague laceration, an admission for pneumonia—when a has a deep respect for scientific medicine. None- nurse approached. “Wanna see someone?” I noted copyright. theless, he likes to tie students into a tradition that the chief complaint and stepped into the room to began long before the invention of the scientific find an elderly couple. -

Burden of Disease: What Is It and Why Is It Important for Safer Food?

Burden of disease: what is it and why is it important for safer food? What is ‘burden of disease’? Burden of disease is concept that was developed in the 1990s by the Harvard School of Public Health, the World Bank and the World Health Organization (WHO) to describe death and loss of health due to diseases, injuries and risk factors for all regions of the world.1 The burden of a particular disease or condition is estimated by adding together: • the number of years of life a person loses as a consequence of dying early because of the disease (called YLL, or Years of Life Lost); and • the number of years of life a person lives with disability caused by the disease (called YLD, or Years of Life lived with Disability). Adding together the Years of Life Lost and Years of Life lived with Disability gives a single-figure estimate of disease burden, called the Disability Adjusted Life Year (or DALY). One DALY represents the loss of one year of life lived in full health (see text box for more explanation and examples). Looking at burden of disease using DALYs can reveal surprises about a population’s health. For example, the Global Burden of Disease 2004 Update suggests that neuropsychiatric conditions are the most important causes of disability in all regions of the world, accounting for around 33% of all years lived with disability among adults aged 15 years and over, but only 2.2% of deaths.2 Therefore while psychiatric disorders are not traditionally regarded as having a major impact on the health of populations, this picture is completely altered when the burden of disease is estimated using DALYs. -

Defining Malaria Burden from Morbidity and Mortality Records, Self Treatment Practices and Serological Data in Magugu, Babati District, Northern Tanzania

Tanzania Journal of Health Research Volume 13, Number 2, April 2011 Defining malaria burden from morbidity and mortality records, self treatment practices and serological data in Magugu, Babati District, northern Tanzania CHARLES MWANZIVA1*, ALPHAXARD MANJURANO2, ERASTO MBUGI3, CLEMENT MWEYA4, HUMPHREY MKALI5, MAGGIE P. KIVUYO6, ALEX SANGA7, ARNOLD NDARO1, WILLIAM CHAMBO8, ABAS MKWIZU9, JOVIN KITAU1, REGINALD KAVISHE11, WIL DOLMANS10, JAFFU CHILONGOLA1 and FRANKLIN W. MOSHA1 1Kilimanjaro Clinical Research Institute, P. O. Box 2236, Moshi, Tanzania 2Joint Malaria Programme, Moshi, Tanzania 3Muhimbili University of Health and Allied Sciences, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania 4Tukuyu Medical Research Centre, Tukuyu, Tanzania 5Tabora Medical Research Centre, Tabora, Tanzania 6Ngongongare Medical Research Station, Usa River, Tanzania 7St. John University of Tanzania, Dodoma, Tanzania 8Amani Medical Research Centre, Muheza, Tanzania 9Magugu Health Centre, Babati, Manyara, Tanzania 10 Radboud University Nijmegen Medical Centre, Nijmegen, The Netherlands Abstract: Malaria morbidity and mortality data from clinical records provide essential information towards defining disease burden in the area and for planning control strategies, but should be augmented with data on transmission intensity and serological data as measures for exposure to malaria. The objective of this study was to estimate the malaria burden based on serological data and prevalence of malaria, and compare it with existing self-treatment practices in Magugu in Babati District of northern Tanzania. Prospectively, 470 individuals were selected for the study. Both microscopy and Rapid Diagnostic Test (RDT) were used for malaria diagnosis. Seroprevalence of antibodies to merozoite surface proteins (MSP- 119) and apical membrane antigen (AMA-1) was performed and the entomological inoculation rate (EIR) was estimated. To complement this information, retrospective data on treatment history, prescriptions by physicians and use of bed nets were collected.