Tomato Leaf Mould

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Maximiliano Agustín Huerta Cabrera

UNIVERSIDAD AUTÓNOMA AGRARIA ANTONIO NARRO DIVISIÓN DE AGRONOMÍA DEPARTAMENTO DE PARASITOLOGÍA Aislamiento e Identificación de Hongos Secundarios al Ácaro (Acolups lycopersici) en Tomate Por: MAXIMILIANO AGUSTÍN HUERTA CABRERA TESIS Presentada como requisito parcial para obtener el título de: INGENIERO AGRÓNOMO PARASITÓLOGO Saltillo, Coahuila, México Octubre de 2017 AGRADECIMIENTOS A DIOS Por concederme lo más maravilloso de la vida, la de MIS PADRES Y MI FAMILIA. Por tender tu mano a ayudar a levantarme, para seguir adelante y obtener un triunfo más, en esta vida; porque tu señor siempre has estado en los momentos más difíciles de mi vida y nunca me abandonas, gracias DIOS MIO, por tus bendiciones SEÑOR. A MI “ALMA TERRA MATER” Por abrigarme en su seno a partir desde el primer día que ingrese hasta el final de mi carrera; por permitir superarme, así como enseñarme a trabajar, lo más hermoso que alimenta a nuestro pueblo mexicano “el campo” , además de obtener la herramienta necesaria para aprovechar al máximo sus frutos. MIS ASESORES Mi más sincero agradecimiento al Dr. Ernesto Cerna Chávez. Por aceptarme como su tesista. A la Dra. Mariana Beltrán Beache por su valioso apoyo como coasesora, y por sus consejos y dedicación que me brindo durante la realización del presente, y así culminar exitosamente mi tesis profesional. Al Dr. Juan Carlos Delgado Ortiz por su valioso tiempo que me brindo apoyándome con el experimento. A la Dra. Yisa María Ochoa Fuentes por su gran apoyo durante toda la carrera como mi tutora, por su gran apoyo y sus -

Analysis of the Emerging Situation of Resistance to Succinate Dehydrogenase Inhibitors in Pyrenophora Teres and Zymoseptoria Tritici in Europe

Universität Hohenheim Institut für Phytomedizin Fachgebiet Phytopathologie Prof. Dr. Ralf T. Vögele Analysis of the emerging situation of resistance to succinate dehydrogenase inhibitors in Pyrenophora teres and Zymoseptoria tritici in Europe Dissertation zur Erlangung des Grades eines Doktors der Agrarwissenschaften vorgelegt der Fakultät Agrarwissenschaften von Dipl. Agr. Biol. Alexandra Rehfus aus Leonberg 2018 Diese Arbeit wurde unterstützt und finanziert durch die BASF SE, Unternehmensbereich Pflanzenschutz, Forschung Fungizide, Limburgerhof. Die vorliegende Arbeit wurde am 15.05.2017 von der Fakultät Agrarwissenschaften der Universität Hohenheim als „Erlangung des Doktorgrades an der agrarwissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Universität Hohenheim in Stuttgart“ angenommen. Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 14.11.2017 1. Dekan: Prof. Dr. R. T. Vögele Berichterstatter, 1. Prüfer: Prof. Dr. R. T. Vögele Mitberichterstatter, 2. Prüfer: Prof. Dr. O. Spring 3. Prüfer: Prof. Dr. Dr. C. P. W. Zebitz Leiter des Kolloquiums: Prof. Dr. J. Wünsche Table of contents III Table of contents Table of contents ................................................................................................. III Abbreviations ..................................................................................................... VII Figures ................................................................................................................. IX Tables ................................................................................................................. -

1 Check-List of Cladosporium Names Frank M. DUGAN, Konstanze

Check-list of Cladosporium names Frank M. DUGAN , Konstanze SCHUBERT & Uwe BRAUN Abstract: DUGAN , F.M., SCHUBERT , K. & BRAUN ; U. (2004): Check-list of Cladosporium names. Schlechtendalia 11 : 1–119. Names of species and subspecific taxa referred to the hyphomycetous genus Cladosporium are listed. Citations for original descriptions, types, synonyms, teleomorphs (if known), references of important redescriptions in literature, illustrations as well as notes are given. This list contains data of 772 taxa, i.e., valid, invalid and illegitime species, varieties and formae as well as herbarium names. Zusammenfassung: DUGAN , F.M., SCHUBERT , K. & BRAUN ; U. (2004): Checkliste der Cladosporium -Namen. Schlechtendalia 11 : 1–119. Namen von Arten und subspezifischen Taxa der Hyphomycetengattung Cladosporium werden aufgelistet. Bibliographische Angaben zur Erstbeschreibung, Typusangaben, Synonyme, die Teleomorphe (falls bekannt), wichtige Literaturhinweise und Abbildungen sowie Anmerkungen werden angegeben. Die vorliegende Liste enthält Namen von 772 Taxa, d. h. gültige, ungültige und illegitime Arten, Varietäten, Formen und auch Herbarnamen. Introduction: Cladosporium Link (LINK 1816) is one of the largest genera of hyphomycetes, comprising more than 772 names, but also one of the most heterogeneous ones, which is not very surprising since all early circumscriptions and delimitations from similar genera were rather vague and imprecise (FRIES 1832, 1849; SACCARDO 1886; LINDAU 1907, etc.). All kinds of superficially similar cladosporioid fungi, i.e., amero- to phragmosporous dematiaceous hyphomycetes with conidia formed in acropetal chains, were assigned to Cladosporium s. lat., ranging from saprobes to plant pathogens as well as human-pathogenic taxa. DE VRIES (1952) and ELLIS (1971, 1976) maintained broad concepts of Cladosporium . ARX (1983), MORGAN - JONES & JACOBSEN (1988), MCKEMY & MORGAN -JONES (1990), MORGAN -JONES & MCKEMY (1990) and DAVID (1997) discussed the heterogeneity of Cladosporium and contributed towards a more natural circumscription of this genus. -

“Caracterización Morfológica Y Molecular De Aislamientos De Cladosporium.”

Universidad Nacional de La Plata Facultad de Ciencias Exactas Licenciatura en Biotecnología y Biología molecular “Caracterización morfológica y molecular de aislamientos de Cladosporium.” Trabajo Final de Grado Alumna: Rocío Medina Director: Ph.D. Pedro Balatti. 2011 Página 1 Caracterización morfológica y molecular de aislamientos de Cladosporium El presente Trabajo Final de Grado de la Carrera de Licenciatura en Biotecnología y Biología Molecular de la Facultad de Ciencias Exactas, Universidad Nacional de La Plata, fue realizado en el Centro de Investigaciones de Fitopatología (CIDEFI) y en el Instituto de Fitopatología Vegetal (INFiVE), de la Facultad de Ciencias Agrarias y Forestales, UNLP, bajo la dirección del Dr. Pedro A. Balatti. Página 2 Caracterización morfológica y molecular de aislamientos de Cladosporium Agradecimientos Deseo expresar mi agradecimiento a la Facultad de Ciencias Exactas por la formación brindada. A mi papá por haber confiado en mí incondicionalmente. A mi mamá y a Rochi, por haberme apoyado y “bancado” todos estos años. Los quiero!! A mi tío, Anto, Belu y Pani; gracias por estar siempre conmigo. A Ange, gracias, sos una segunda mamá para mi! A mis amigas incondicionales, que en todas las etapas de mi vida me apoyaron y acompañaron, gracias Bren, Chulis, Luli, Verito, Pao y Vick. Al Dr. Pedro Balatti por su paciencia, atención, predisposición, por intentar enseñarme algo de todo lo que sabe, y por su confianza en mí. A Silvina y Ale, gracias por TODO. A Mario por transmitirme su pasión por los hongos. A los chicos del INFIVE, Ismael, Darío, Pepe, Grace; Emi, Ernest y Car, quienes me apoyaron y ayudaron siempre. -

Cercosporoid Fungi of Poland Monographiae Botanicae 105 Official Publication of the Polish Botanical Society

Monographiae Botanicae 105 Urszula Świderska-Burek Cercosporoid fungi of Poland Monographiae Botanicae 105 Official publication of the Polish Botanical Society Urszula Świderska-Burek Cercosporoid fungi of Poland Wrocław 2015 Editor-in-Chief of the series Zygmunt Kącki, University of Wrocław, Poland Honorary Editor-in-Chief Krystyna Czyżewska, University of Łódź, Poland Chairman of the Editorial Council Jacek Herbich, University of Gdańsk, Poland Editorial Council Gian Pietro Giusso del Galdo, University of Catania, Italy Jan Holeksa, Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań, Poland Czesław Hołdyński, University of Warmia and Mazury in Olsztyn, Poland Bogdan Jackowiak, Adam Mickiewicz University, Poland Stefania Loster, Jagiellonian University, Poland Zbigniew Mirek, Polish Academy of Sciences, Cracow, Poland Valentina Neshataeva, Russian Botanical Society St. Petersburg, Russian Federation Vilém Pavlů, Grassland Research Station in Liberec, Czech Republic Agnieszka Anna Popiela, University of Szczecin, Poland Waldemar Żukowski, Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań, Poland Editorial Secretary Marta Czarniecka, University of Wrocław, Poland Managing/Production Editor Piotr Otręba, Polish Botanical Society, Poland Deputy Managing Editor Mateusz Labudda, Warsaw University of Life Sciences – SGGW, Poland Reviewers of the volume Uwe Braun, Martin Luther University of Halle-Wittenberg, Germany Tomasz Majewski, Warsaw University of Life Sciences – SGGW, Poland Editorial office University of Wrocław Institute of Environmental Biology, Department of Botany Kanonia 6/8, 50-328 Wrocław, Poland tel.: +48 71 375 4084 email: [email protected] e-ISSN: 2392-2923 e-ISBN: 978-83-86292-52-3 p-ISSN: 0077-0655 p-ISBN: 978-83-86292-53-0 DOI: 10.5586/mb.2015.001 © The Author(s) 2015. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits redistribution, commercial and non-commercial, provided that the original work is properly cited. -

Tomato Leaf Mold

Tomato Leaf Mold Passalora fulva Leaf mold, caused by the fungus Passalora fulva (previ- Warm temperatures (70-75 degrees F) and moderately ously called Fulvia fulva or Cladosporium fulvum), is one high relative humidity (75-90 percent) are conducive to of the most common diseases of tomatoes produced in infection and disease development. Under these condi- greenhouses and high tunnels. In the Southern United tions, a large number of fungal spores are produced on the States, tomato leaf mold can cause severe defoliation and lower leaf surfaces and disseminated by wind, water, rain yield losses to tomatoes produced in the field, especially splash, tools and insects. during the spring and early summer. The disease develops Contaminated seeds are thought to be the primary rapidly during wet and humid conditions, spreading from source of the fungus. In temperate climates or greenhous- lower to upper leaves and resulting in significant yield es, the fungus can survive on plant debris and in the soil as losses if it is left unmanaged (Figure 1). spores or resting structures (sclerotia) for up to a year. Successful management of leaf mold requires early The length of time that the fungus survives in the detection and accurate identification of the disease. soil or on plant debris in the Deep South has not been Symptoms begin with yellow diffuse spots or patches on determined, but moderate winter temperatures may allow the upper leaf surfaces. As the disease progresses, these spores and sclerotia to survive for more than a year in spots enlarge into yellow to light brown areas with unde- the South. -

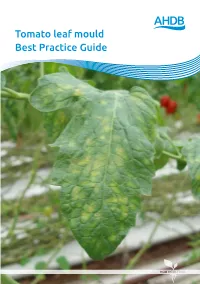

Tomato Leaf Mould Best Practice Guide

Tomato leaf mould Best Practice Guide Contents 3 Background 4 The pathogen 6 Control 11 Spray application 12 Crop husbandry 13 Resistant stains The information in this guide was compiled by Dave Kaye and Sarah Mayne, RSK ADAS We are grateful to the growers who provided answers to the growers’ questionnaire as well as additional information on control of tomato leaf mould during 2015-2016 Photography: All images are copyright of Dave Kaye, RSK ADAS, except page 12, Derek Hargreaves and pages 2 and 15, Ivan Timov. 2 Background Tomato leaf mould (Passalora fulva) can be This best practice guide provides one of the most destructive foliar diseases information on disease symptoms and of tomato when the crop is grown under epidemiology, as well as information on humid conditions. how to manage the disease using cultural and chemical measures, effective crop It has recently reappeared in some UK husbandry, varietal resistance and plant crops, and has persisted overwinter on a protection products. few nurseries between one crop and the next. Prevention of the disease by managing the glasshouse environment is much easier than managing the disease. Top tips for preventing tomato leaf mould 1 Monitor tomato crops for P. fulva from April onwards. 2 Maintain excellent hygiene standards throughout the entire season. 3 At sites with a history of leaf mould, measures should be implemented early to prevent P. fulva establishment. 4 Identify and monitor disease hotspots where P. fulva infections occur early each year, and treat accordingly. 5 Minimise periods of relative humidity (RH) above 85 per cent and keep the crop well ventilated. -

Cladosporium Fulvum

Fungal Genetics and Biology 44 (2007) 415–429 www.elsevier.com/locate/yfgbi Mating-type genes and the genetic structure of a world-wide collection of the tomato pathogen Cladosporium fulvum Ioannis Stergiopoulos a, Marizeth Groenewald a,b, Martijn Staats a, Pim Lindhout c,1, Pedro W. Crous a,b, Pierre J.G.M. De Wit a,¤ a Laboratory of Phytopathology, Wageningen University and Research Centre, Binnenhaven 5, 6709 PD Wageningen, The Netherlands b Centraalbureau voor Schimmelcultures, Fungal Biodiversity Centre, Uppsalalaan 8, 3584 CT Utrecht, The Netherlands c Laboratory of Plant Breeding, Wageningen University and Research Centre, Droevendaalsesteeg 1, 6708 PB Wageningen, The Netherlands Received 30 June 2006; accepted 7 November 2006 Available online 18 December 2006 Abstract Two mating-type genes, designated MAT1-1-1 and MAT1-2-1, were cloned and sequenced from the presumed asexual ascomycete Cladosporium fulvum (syn. Passalora fulva). The encoded products are highly homologous to mating-type proteins from members of the Mycosphaerellaceae, such as Mycosphaerella graminicola and Cercospora beticola. In addition, the two MAT idiomorphs of C. fulvum showed regions of homology and each contained one additional putative ORF without signiWcant similarity to known sequences. The dis- tribution of the two mating-type genes in a world-wide collection of 86 C. fulvum strains showed a departure from a 1:1 ratio (2 D 4.81, df D 1). AFLP analysis revealed a high level of genotypic diversity, while strains of the fungus were identiWed with similar virulence spec- tra but distinct AFLP patterns and opposite mating-types. These features could suggest the occurrence of recombination in C. -

Host Range, Geographical Distribution and Current Accepted Names of Cercosporoid and Ramularioid Species in Iran

Current Research in Environmental & Applied Mycology (Journal of Fungal Biology) 9(1): 122–163 (2019) ISSN 2229-2225 www.creamjournal.org Article Doi 10.5943/cream/9/1/13 Host range, geographical distribution and current accepted names of cercosporoid and ramularioid species in Iran Pirnia M Department of Plant Protection, Faculty of Agriculture, University of Zabol, Zabol, Iran Pirnia M 2019 – Host range, geographical distribution and current accepted names of cercosporoid and ramularioid species in Iran. Current Research in Environmental & Applied Mycology (Journal of Fungal Biology) 9(1), 122–163, Doi 10.5943/cream/9/1/13 Abstract Comprehensive up to date information of cercosporoid and ramularioid species of Iran is given with their hosts, geographical distribution and references. A total of 186 taxa belonging to 24 genara are listed. Among them, 134 taxa were belonged to 16 Cercospora and Cercospora-like genera viz. Cercospora (62 species), Cercosporidium (1 species), Clypeosphaerella (1 species), Fulvia (1 species), Graminopassalora (1 species), Neocercospora (1 species), Neocercosporidium (1 species), Nothopassalora (1 species), Paracercosporidium (1 species), Passalora (21 species), Pseudocercospora (36 species), Rosisphaerella (1 species), Scolecostigmina (2 species), Sirosporium (2 species), Sultanimyces (1 species) and Zasmidium (1 species); and 52 taxa were belonged to 8 Ramularia and Ramularia-like genera viz. Cercosporella (2 species), Microcyclosporella (1 species), Neoovularia (2 species), Neopseudocercosporella (1 species), Neoramularia (2 species), Ramularia (42 species), Ramulariopsis (1 species) and Ramulispora (1 species). Key words – anamorphic fungi – biodiversity – Cercospora-like genera – Ramularia-like genera – west of Asia Introduction Cercosporoid and ramularioid fungi are traditionally related to the genus Mycospharella Johanson. Sivanesan (1984) investigated teleomorph-anamorph connexions in bitunicate ascomycetes and cited that Mycosphaerella is related to some anamorphic genera viz. -

Tomato Leaf Mold

Plant Pathology and Plant-Microbe Biology Section School of Integrative Plant Science Cornell Cooperative Extension Cornell AgriTech Tomato Leaf Mold Introduction Tomato leaf mold is a foliar disease that is especially problematic in greenhouse and high tunnels. It was first described in 1883 as a pathogen that causes leaf lesions. It is less common in the field compared to greenhouses and high tunnels. With the rise of high tunnel construction in New York State through assistance programs by the Natural Resources Conservation Service, tomato leaf mold is appearing more frequently. High tunnels allow for season extension of high value crops such as tomatoes, yet the structures are also conducive to the growth of tomato leaf mold, which favors humid, dry conditions. Despite the slower progression of disease compared to a pathogen such as Phytophthora infestans, management is still crucial because tomatoes are a high value crop and consistent yields are an important source of income for growers. Causal Agent Tomato leaf mold is caused by a fungal pathogen called Passalora fulva (syn. Cladosporium fulvum). It is an ascomycete fungus that lives on living tomato leaves. The fungus produces conidia that infect the lower surfaces of leaves (Figure 1). Upon landing on leaves, the fungus lands and enters plant stomata used in gas exchange. The stomata become clogged and tomato plants cannot respire well, resulting in wilting, defoliation, and infection. Figure 1. Left: the fungus Passalora fulva isolated from infected tomato leaves. Right: the fungus under the microscope. Symptoms Disease symptoms first appear after seven days, as light green spots on leaves. -

Passalora Fulva (Cooke) U

DIRECCIÓN GENERAL DE SANIDAD VEGETAL CENTRO NACIONAL DE REFERENCIA FITOSANITARIA Área de Diagnóstico Fitosanitario Laboratorio de Micología Protocolo de Diagnóstico: Passalora fulva (Cooke) U. Braun & Crous, 2003 (Moho de la hoja del tomate) Tecámac, Estado de México, julio 2019 Senasica, agricultura sana para el bienestar Aviso El presente protocolo de diagnóstico fitosanitario fue desarrollado en las instalaciones de la Dirección del Centro Nacional de Referencia Fitosanitaria (CNRF), de la Dirección General de Sanidad Vegetal (DGSV) del Servicio Nacional de Sanidad, Inocuidad y Calidad Agroalimentaria (SENASICA), con el objetivo de diagnosticar específicamente la presencia o ausencia de Passalora fulva. La metodología descrita tiene un sustento científico que respalda los resultados obtenidos al aplicarlo. La incorrecta implementación o variaciones en la metodología especificada en este documento de referencia pueden derivar en resultados no esperados, por lo que es responsabilidad del usuario seguir y aplicar el protocolo de forma correcta. La presente versión podrá ser mejorada y/o actualizada quedando el registro en el historial de cambios. I. ÍNDICE 1. OBJETIVO Y ALCANCE DEL PROTOCOLO ............................................................................................. 1 2. INTRODUCCIÓN .............................................................................................................................................. 1 2.1 Información sobre la plaga ........................................................................................................................... -

Durph, Aardappel En Phytophthora KNPV

Gewasbescherming, jaargang 41, juni 2010 3NUMMER DuRPh, aardappel en Phytophthora KNPV - voorjaarsvergadering Mededelingenblad van de Koninklijke Nederlandse Plantenziektekundige Vereniging de Koninklijke Mededelingenblad van GWSBSCHRMNG [ Mededelingenblad van de Koninklijke Nederlandse Plantenziektekundige Vereniging Gewasbescherming, Huijbers’ Administratiekantoor, Afbeelding voorpagina het mededelingenblad van de KNPV, Postbus 244, 6700 AE Wageningen, tel.: Normale vatbare en resistente verschijnt zes keer per jaar in de 0317-421545, e-mail: [email protected]. GM-aardappels. Haverkort et al., p. 119. oneven maand. Kopij inleveren voor Alle overige vragen kunt u richten aan de de 20e van de voorafgaande maand. secretaris van de KNPV, Jan Bouwman, Postbus 31, 6700 AA Wageningen, e-mail: Redactie e-mail: [email protected] [email protected] Jan-Kees Goud (WU, Fytopa- Postbank: 92 31 65, ABN-AMRO: Graanziekten thologie), hoofdredacteur, 53.93.39.768, ten name van KNPV, voorzitter: G.J.H. Kema (PRI) e-mail: [email protected]; Wageningen, Betalingen o.v.v. uw naam. secretaris: H.T.A.M. Schepers José van Bijsterveldt-Gels (PD), secretaris, PPO, Postbus 430, 8200 AK Lelystad [email protected]; Bestuur Koninklijke Nederlandse e-mail: [email protected] Marianne Roseboom-de Vries, Plantenziektekundige Vereniging administratief medewerker, G.H.J. Kema (PRI), voorzitter Fytobacteriologie [email protected]; vacant, secretaris voorzitter: J.M. Raaijmakers (WU) Linus Franke (PRI) J.J. Bouwman (Nefyto), penningmeester secretaris: J. van Doorn [email protected] S. Sütterlin (LNV) PPO-BB, Postbus 85, 2160 AB Lisse Erno Bouma (Agrovision), L. Bastiaans (WU-DPW) e-mail: [email protected] [email protected]; Thomas Lans J.S.