Battle of Surigao Strait

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Analysis of the Battle of Surigao Strait by Walter S

Analysis of the Battle of Surigao Strait By Walter S. Zapotoczny Today, all great nations recognize basic principles of war and incorporate them in their doctrine. The lists vary from nation to nation. In the Western World, the accepted principles are essentially a post-Napoleonic conception, advanced by Clausewitz, the great Prussian philosopher of war in the early nineteenth century, and his contemporary, Jomini, the well- known French general and theorist. These principles are common to ground, as well as, naval operations. The United States Army recognizes nine principles and includes them in its Field Manual 100-5. Their proper application, the Army holds, is essential to the exercise of effective command and to the successful conduct of military operations. These nine principles provide an effective model to analyze the Battle of Surigao Strait. OBJECTIVE The first of the nine principles is Objective. The FM 100-5 definition states that every military operation must be directed toward a clearly defined, decisive, and attainable objective. The ultimate military objective of war is the destruction of the enemy's armed forces and his will to fight. The objective of each operation must contribute to this ultimate objective. Each intermediate objective must be such that its attainment will most directly, quickly, and economically contribute to the purpose of the operation. The selection of an objective is based upon consideration of the means available, the enemy, and the area of operations. Every commander must understand and clearly define his objective and consider each contemplated action in light thereof. Once planes from Admiral Halsey’s carriers spotted Admiral Nishimura’s fleet making for the Surigao Strait and Admiral Kurita’s large fleet coming through the San Bernardino Strait, it was obvious to Admiral Kinkaid that the Japanese planed to converge in Leyte Gulf to attack MacArthur’s invasion ships. -

Pdf (Accessed Department of Environment and Natural September 1, 2010)

OceanTEFFH O icial MAGAZINEog OF the OCEANOGRAPHYraphy SOCIETY CITATION May, P.W., J.D. Doyle, J.D. Pullen, and L.T. David. 2011. Two-way coupled atmosphere-ocean modeling of the PhilEx Intensive Observational Periods. Oceanography 24(1):48–57, doi:10.5670/ oceanog.2011.03. COPYRIGHT This article has been published inOceanography , Volume 24, Number 1, a quarterly journal of The Oceanography Society. Copyright 2011 by The Oceanography Society. All rights reserved. USAGE Permission is granted to copy this article for use in teaching and research. Republication, systematic reproduction, or collective redistribution of any portion of this article by photocopy machine, reposting, or other means is permitted only with the approval of The Oceanography Society. Send all correspondence to: [email protected] or The Oceanography Society, PO Box 1931, Rockville, MD 20849-1931, USA. downloaded FROM www.tos.org/oceanography PHILIppINE STRAITS DYNAMICS EXPERIMENT BY PAUL W. MAY, JAMES D. DOYLE, JULIE D. PULLEN, And LAURA T. DAVID Two-Way Coupled Atmosphere-Ocean Modeling of the PhilEx Intensive Observational Periods ABSTRACT. High-resolution coupled atmosphere-ocean simulations of the primarily controlled by topography and Philippines show the regional and local nature of atmospheric patterns and ocean geometry, and they act to complicate response during Intensive Observational Period cruises in January–February 2008 and obscure an emerging understanding (IOP-08) and February–March 2009 (IOP-09) for the Philippine Straits Dynamics of the interisland circulation. Exploring Experiment. Winds were stronger and more variable during IOP-08 because the time the 10–100 km circulation patterns period covered was near the peak of the northeast monsoon season. -

The Project for Study on Improvement of Bridges Through Disaster Mitigating Measures for Large Scale Earthquakes in the Republic of the Philippines

THE REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC WORKS AND HIGHWAYS (DPWH) THE PROJECT FOR STUDY ON IMPROVEMENT OF BRIDGES THROUGH DISASTER MITIGATING MEASURES FOR LARGE SCALE EARTHQUAKES IN THE REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES FINAL REPORT MAIN TEXT [2/2] DECEMBER 2013 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY (JICA) CTI ENGINEERING INTERNATIONAL CO., LTD CHODAI CO., LTD. NIPPON KOEI CO., LTD. EI JR(先) 13-261(3) Exchange Rate used in the Report is: PHP 1.00 = JPY 2.222 US$ 1.00 = JPY 97.229 = PHP 43.756 (Average Value in August 2013, Central Bank of the Philippines) LOCATION MAP OF STUDY BRIDGES (PACKAGE B : WITHIN METRO MANILA) i LOCATION MAP OF STUDY BRIDGES (PACKAGE C : OUTSIDE METRO MANILA) ii B01 Delpan Bridge B02 Jones Bridge B03 Mc Arthur Bridge B04 Quezon Bridge B05 Ayala Bridge B06 Nagtahan Bridge B07 Pandacan Bridge B08 Lambingan Bridge B09 Makati-Mandaluyong Bridge B10 Guadalupe Bridge Photos of Package B Bridges (1/2) iii B11 C-5 Bridge B12 Bambang Bridge B13-1 Vargas Bridge (1 & 2) B14 Rosario Bridge B15 Marcos Bridge B16 Marikina Bridge B17 San Jose Bridge Photos of Package B Bridges (2/2) iv C01 Badiwan Bridge C02 Buntun Bridge C03 Lucban Bridge C04 Magapit Bridge C05 Sicsican Bridge C06 Bamban Bridge C07 1st Mandaue-Mactan Bridge C08 Marcelo Fernan Bridge C09 Palanit Bridge C10 Jibatang Bridge Photos of Package C Bridges (1/2) v C11 Mawo Bridge C12 Biliran Bridge C13 San Juanico Bridge C14 Lilo-an Bridge C15 Wawa Bridge C16 2nd Magsaysay Bridge Photos of Package C Bridges (2/2) vi vii Perspective View of Lambingan Bridge (1/2) viii Perspective View of Lambingan Bridge (2/2) ix Perspective View of Guadalupe Bridge x Perspective View of Palanit Bridge xi Perspective View of Mawo Bridge (1/2) xii Perspective View of Mawo Bridge (2/2) xiii Perspective View of Wawa Bridge TABLE OF CONTENTS Location Map Photos Perspective View Table of Contents List of Figures & Tables Abbreviations Main Text Appendices MAIN TEXT PART 1 GENERAL CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................... -

Dynamics of Atmospheres and Oceans Seasonal Surface Ocean

Dynamics of Atmospheres and Oceans 47 (2009) 114–137 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Dynamics of Atmospheres and Oceans journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/dynatmoce Seasonal surface ocean circulation and dynamics in the Philippine Archipelago region during 2004–2008 Weiqing Han a,∗, Andrew M. Moore b, Julia Levin c, Bin Zhang c, Hernan G. Arango c, Enrique Curchitser c, Emanuele Di Lorenzo d, Arnold L. Gordon e, Jialin Lin f a Department of Atmospheric and Oceanic Sciences, University of Colorado, UCB 311, Boulder, CO 80309, USA b Ocean Sciences Department, University of California, Santa Cruz, CA, USA c IMCS, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ, USA d EAS, Georgia Institute of Technology, Atlanta, GA, USA e Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, Columbia University, Palisades, NY, USA f Department of Geography, Ohio State University, Columbus, OH, USA article info abstract Article history: The dynamics of the seasonal surface circulation in the Philippine Available online 3 December 2008 Archipelago (117◦E–128◦E, 0◦N–14◦N) are investigated using a high- resolution configuration of the Regional Ocean Modeling System (ROMS) for the period of January 2004–March 2008. Three experi- Keywords: ments were performed to estimate the relative importance of local, Philippine Archipelago remote and tidal forcing. On the annual mean, the circulation in the Straits Sulu Sea shows inflow from the South China Sea at the Mindoro and Circulation and dynamics Balabac Straits, outflow into the Sulawesi Sea at the Sibutu Passage, Transport and cyclonic circulation in the southern basin. A strong jet with a maximum speed exceeding 100 cm s−1 forms in the northeast Sulu Sea where currents from the Mindoro and Tablas Straits converge. -

Republic Act No. 9355 an Act Creating the Province of Dinagat Islands

W No. 884 Begun and held in Metro Manila, on Monaay, the twenty-fourth day of July, two thousand six. [REPUBLIC ACT NO. 9355 AN ACT CREATING THE PROVINCE OF DINAGAT ISLANDS Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Represeniaiives of the Philippines in Congress assembled. ARTICLE I GENERALPROVISIONS SECTION1. Title. - This Act shall be known as the "Charter of the Province of Dinagat Islands." SEC.2. Province ofDinugut Islands. - There is hereby created a new province from the present Province of Surigao del Norte to be known as the Province of Dinagat Islands consisting of the municipalities of Basilisa, Cagdianao, Dinagat, Libjo (Albor), Loreto, San Jose and Tubajon with the following boundaries: 2 Bounded on the North, starting from the desolation point is Surigao Strait; on the East by the Philippine Sea; on the South- East by Dinagat sound; on the South by Gaboc Channel and Nonoc Island; on the South-Westby Awasan Bay, Hanigad Island and Hikdop Island; and on the West by Surigao Strait. The geographic positions of four (4) selected outer most points of the main island of the new Province of Dinagat Islands, with latitude and longitude are as follows: SELECTED OUTER MOST POINTS LATITUDE LONGITUDE REMARKS (1) Northernmost Point lO"28'15.6173"125"42'23.5800" Desolation Point (2) Eastem most Point 9"53'37.1G57' 125"42'20.3417" Along Dinagat Sound (3). Southern inmt Point 9"51'12.0722" 125°39151.1G43" Along Gaboe Channel (4) Westernmost Point 10"08'14.3014" 125"28'16.G544" Tungopoint The Province of Dinagat Islands contains an approximate land area of eighty thousand two hundred twelve hectares (80,212 has.) or 802.12 sq. -

INBOUND THROUGH the SURIGAO STRAIT the Following Is a Summary

INBOUND THROUGH THE SURIGAO STRAIT The following is a summary of advice and suggestions provided by a number of cruising yachtsmen who all wish you the very smoothest of sailing. Please note: the views and comments expressed in this document are offered in the interests of the pleasure, safety and security of all, and do not necessarily reflect the policy or opinion of Puerto Galera Yacht Club, Inc. If you find anything in these notes that is not quite accurate or, if you wish to add new information, please contact the: [email protected] LITTLE KNOWN FACTS The Philippine Deep 40 miles due east of Siargao Island lies the Philippine Deep, which was first surveyed by the German vessel Emden in 1927. The Deep reaches a depth of more than 35,400 feet, whereas the height of Mt Everest is less than 30,000 feet. The GPS reading at the deepest point is 9° 42’N, 126° 50’E. Don’t plan to drop anchor here! The Surigao Strait This is the same route taken by Magellan when he first entered this vast archipelago, in 1521, and claimed it for the King of Spain. The islands have ever since been known as ‘the Philippines’, in honour of the King. The Strait itself is deep and free from dangers, with the shorelines steep too. The only challenge is the tidal flow – up to 8 knots in places, when in full flood. WEATHER The Philippine islands experience two distinct ‘seasons’ of weather: the NE monsoon, from November through April; and, the SW monsoon from May through October. -

![RIOP09, Leg 2 [Final] Report](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0759/riop09-leg-2-final-report-2890759.webp)

RIOP09, Leg 2 [Final] Report

RIOP09, Leg 2 [final] Report Regional Cruise Intensive Observational Period 2009 RIOP09 R/V Melville, 27 February – 21 March 2009 Arnold L. Gordon, Chief Scientist Leg 2 [final] Report Manila to Dumaguete, 9 March to 21 March 2009 “Pidgie” RIOP09 Leg 2 Mascot, Dumaguete-Manila Preface: While this report covers RIOP09 leg 2, it also serves as the final report, thus the introductory section of the leg 1 report is repeated. For completeness within a single document the preliminary analysis [or better stated: first impressions of the story told by the RIOP09 data set] included in the leg 1 report are given in the appendices section of this report. Other appendices describe specific components of RIOP09: CTD-O2; LADCP; hull ADCP; PhilEx moorings; the Philippine research program: Chemistry/Bio- optics; and sediment trap moorings. I Introduction: The second Regional IOP of PhilEx, RIOP09, aboard the R/V Melville began from Manila on 27 February. We return to Manila on 21 March 2009, with an intermediate port stop for personnel exchange in Dumaguete, Negros, on 9 March. This divides the RIOP09 into 2 legs, with CTD-O2/LADCP/water samples [oxygen, nutrients]; hull ADCP and underway-surface data [met/SSS/SST/Chlorophyll] on both legs, and the recovery of: 4 PhilEx, 2 Sediment Trap moorings of the University of Hamburg, and an EM-Apex profiler, on leg 2. The general objective of RIOP09, as with the previous regional cruises is to provide a view of the stratification and circulation of the Philippine seas under varied monsoon condition, as required to support of PhilEx DRI goals directed at ocean 1 RIOP09, Leg 2 [final] Report dynamics within straits. -

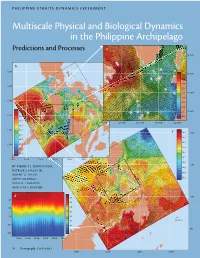

Multiscale Physical and Biological Dynamics in the Philippine Archipelago Predictions and Processes a 12°30’N

PHILIppINE STRAITS DYNAMICS EXPERIMENT Multiscale Physical and Biological Dynamics in the Philippine Archipelago Predictions and Processes a 12°30’N b 15°N 28.5 12°00’N 28.2 27.9 14°N 27.6 27.3 11°30’N 27.0 13°N 26.7 26.4 28.5 26.1 11°00’N 12°N 28.2 25.8 27.9 120°00’E 120°30’E 121°00’E 121°30’E 122°00’E 27.6 11°N 27.3 c 29.7 20°N 27.0 29.0 26.7 28.3 10°N 26.4 27.6 26.1 25.8 26.9 26.2 118°E 119°E 120°E 121°E 122°E 123°E 124°E 25.5 15°N BY PIERRE F.J. LERMUSIAUX, 24.8 PATRICK J. HALEY JR., 24.0 WAYNE G. LESLIE, 23.4 ARPIT AgARWAL, OLEG G. LogUTov, AND LISA J. BURTon d 28 10°N -50 26 24 -100 22 -150 20 -1 18 40 cm s -200 16 5°N 14 -250 06Feb 11Feb 16Feb 21Feb 26Feb 03Mar 70 Oceanography | Vol.24, No.1 115°E 120°E 125°E 130°E ABSTRACT. The Philippine Archipelago is remarkable because of its complex of which are known to be among the geometry, with multiple islands and passages, and its multiscale dynamics, from the strongest in the world (e.g., Apel et al., large-scale open-ocean and atmospheric forcing, to the strong tides and internal 1985). The purpose of the present study waves in narrow straits and at steep shelfbreaks. -

ADMIRALTY Charts to Be Published April

DATEMA DELFZIJL B.V. ROTTERDAM BRANCH ZEESLUIZEN 8 GALVANISTRAAT 148 9936 HX DELFZIJL 3029 AD ROTTERDAM P.O. BOX 101 THE NETHERLANDS 9930 AC DELFZIJL T +31 (0)10 436 61 88 ADMIRALTY charts THE NETHERLANDS F +31 (0)10 436 55 11 T +31 (0)596 63 52 52 to be published April F +31 (0)596 61 52 45 WWW.DATEMA.NL ADMIRALTY Charts to be Published 13 April 2017 860 Morocco - West Coast, Approaches to Casablanca and Mohammedia. 110 International Chart Series, North Sea - Netherlands, Westkapelle to Stellendam and Maasvlakte. CAUTION – NEW ROUTEING MEASURES – NEED TO RETAIN PREVIOUS EDITION OF THIS CHART* 359 Mexico - East Coast, Dos Bocas Terminal. 644 International Chart Series, Mozambique, Baía de Maputo. 646 Mozambique, Porto de Maputo. 1112 France - North Coast, Cherbourg. 1114 France - North Coast, Approaches to Cherbourg, Cap de la Hague to Pointe de Barfleur. 1259 Korea - South Coast, Busan and Masan. 1307 Mexico - East Coast, Bahía de Campeche. 1320 Irish Sea, Fleetwood to Douglas. 1630 International Chart Series, North Sea, Netherlands, West Hinder and Outer Gabbard to Vlissingen and Scheveningen. CAUTION – NEW ROUTEING MEASURES – NEED TO RETAIN PREVIOUS EDITION OF THIS CHART* 1826 International Chart Series, British Isles, Irish Sea, Eastern Part. 1882 England - East Coast, Bridlington and Filey. 2135 France - North Coast, Pointe de Barfleur to Pointe de La Percée. 2241 Baltic Sea, Entrance to the Gulf of Finland. 2248 Baltic Sea, Gulf of Finland, Western Part. 2264 Baltic Sea, Gulf of Finland, Eastern Part. 2626 Mexico - East Coast, Bay of Campeche. 2656 English Channel, Central Part. 2716 International Chart Series, Baltic Sea, Latvia, Ventspils. -

Philippine Marginal Seas NAST/NRCP/DOST

Marginal Seas of the Philippines:a marginal sea is a sea Status and Challengespartially enclosed by islands, archipelagos, or peninsulas, adjacent to or Cesar L Villanoy widely open to the open South China Sea Marine Science Instituteocean at the surface, West Philippine Sea and/or bounded by East UniversitySea of the Philippines submarine ridges on the Sulu Sea sea floor - Wikipedia Sulawesi Sea RTD on Philippine Marginal Seas NAST/NRCP/DOST Smaller Marginal Seas within the Archipelago San Bernardino Strait N Sibuyan Sea Sill depth 92m S Sibuyan Sea Visayan Sea Surigao Strait Camotes Sea Sill depth 52m Bohol Sea Bathymetry Philippine archipelagic basins are deep but separated by shallower topographic barriers of sills Name Max Depth Sill Depth (m) Surface Area (km2) South China Sea >5,000 2,200 3,352,500 Sulawesi Sea >5,000 1,350 430,000 Sulu Sea >5,000 520 (Panay) 287,500 350 (Sibutu) Bohol Sea 1,800 420 (Sulu) 26,150 52 (Surigao Strait) North Sibuyan 1,700 500 9,500 South Sibuyan 1,350 400 7,500 Visayan 50 Shallow sea 8,900 Camotes 800 <300 8,600 Deep water flowing over sills Temperature and oxygen profiles below 300m in the different basins Chlorophyll Forcing in the Marginal Seas Asian Monsoon Winds earth.nullschool.net Chavanne et al., 2002) Wind jets in the Verde Passage forcing local upwelling May et al, 2011 Bohol Sea Marginal Sea with significant flow from Pacific to Sulu Sea Bohol Jet and Iligan Bay Eddy Semi-enclosed nature of archipelagic basins and implications to reef connectivity Kool et al, 2011 Summary • Archipelagic -

Call the Hands

CALL THE HANDS Issue No.36 November 2019 From the President Welcome to this edition of Call the Hands and two accompanying occasional papers. I trust you find them of interest. In the October edition of Call the Hands we highlighted the 75th Anniversary of the battles of Leyte Gulf which occurred between 20 and 25 October. The series of sea battles in and around Leyte Gulf in October 1944 marked a turning point in the Pacific war. Is was a decisive battle in which the entire and still powerful Japanese Navy was committed. The Japanese force was attempting to destroy the vast American fleet of vessels supporting the strategically critical amphibious landings on Leyte. Given the significance of these operations to Australia and the historic role played by participating Royal Australian Naval ships, this edition of Call the Hands continues coverage of the battles and provides numerous additional reading references. It is important that more Australians understand the significance of these battles. Occasional Paper 66 by David Scott, a junior sailor in HMAS Arunta was first published by the Society in September 2016. It is a gripping account of HMAS Arunta’s role in the Battles of Leyte Gulf. It combines personal observations and experiences with a more strategic perspective of the multiple actions fought in late October 1944. The paper also provides a strong sense of the arduous, uncomfortable and stressful conditions experienced by the ships company who spent extraordinary periods of time closed up at action stations. Other papers, listed as recommended reading include accounts by Vice Admiral Sir John Collins and Rear Admiral Guy Griffiths. -

PART 3 Scale 1: Publication Edition Scale 1: Publication Edition Scale 1: Publication Edition 13 W Approaches to Cebu Harbour 35,000 Sept

Natural Date of New Natural Date of New Natural Date of New Chart No. Title of Chart or Plan Chart No. Title of Chart or Plan Chart No. Title of Chart or Plan PART 3 Scale 1: Publication Edition Scale 1: Publication Edition Scale 1: Publication Edition 13 w Approaches to Cebu Harbour 35,000 Sept. 2001 Apr. 2011 1680w Teluk Darvel 100,000 Oct. 1971 Nov. 2009 3626w Approaches to Kota Kinabalu and Teluk Sapangar 35,000 Jan. 1990 - 14 w Cebu Harbour 12,500 June 2001 Apr. 2011 1681w Northern Shore of Sibuko Bay 97,000 Feb. 1893 Mar. 2005 3728w Pulau-Pulau Mantanani to Pulau Banggi 150,000 Mar. 1990 Nov. 2009 287 w Eastern Approaches to Balabac Strait 300,000 Mar. 1990 Feb. 2011 1686w Kunak and Approaches 20,000 Feb. 1968 - 3801w Plans in the Philippine Islands - Apr. 1964 Nov. 2000 340 w Daya Wan and Approaches to Huizhou 60,000 Sept. 2010 Mar. 2011 1844w Brunei Bay and Approaches 75,000 Nov. 1990 Apr. 2010 A Bais 40,000 341 w Macao to Hong Kong 75,000 Nov. 1989 July 2011 Approaches to Sipitang Wharf 25,000 B San Jose de Buenavista 10,000 342 w Shekou Gang to Mawan Gang 15,000 Aug. 2001 Jan. 2010 1852w Tanjung Mangkapadie to Tawau including Lingkas, Bunyu and - June 1994 - C Tagbilaran 20,000 343 w Zhujiang Kou including Approaches to Chiwan, Shekou and Nansha Gang 75,000 Nov. 1989 Nov. 2010 Approaches D San Carlos 50,000 Nansha Gang 30,000 Approaches to Lingkas and Bunyu 100,000 E Port Canoan 5,000 J4 344 w Shanban Zhou to Nizhou Tou 25,000 Aug.