The State of the Coalfields

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wales Regional Geology RWM | Wales Regional Geology

Wales regional geology RWM | Wales Regional Geology Contents 1 Introduction Subregions Wales: summary of the regional geology Available information for this region 2 Rock type Younger sedimentary rocks Older sedimentary rocks 3 Basement rocks Rock structure 4 Groundwater 5 Resources 6 Natural processes Further information 7 - 21 Figures 22 - 24 Glossary Clicking on words in green, such as sedimentary or lava will take the reader to a brief non-technical explanation of that word in the Glossary section. By clicking on the highlighted word in the Glossary, the reader will be taken back to the page they were on. Clicking on words in blue, such as Higher Strength Rock or groundwater will take the reader to a brief talking head video or animation providing a non-technical explanation. For the purposes of this work the BGS only used data which was publicly available at the end of February 2016. The one exception to this was the extent of Oil and Gas Authority licensing which was updated to include data to the end of June 2018. 1 RWM | Wales Regional Geology Introduction This region comprises Wales and includes the adjacent inshore area which extends to 20km from the coast. Subregions To present the conclusions of our work in a concise and accessible way, we have divided Wales into 6 subregions (see Figure 1 below). We have selected subregions with broadly similar geological attributes relevant to the safety of a GDF, although there is still considerable variability in each subregion. The boundaries between subregions may locally coincide with the extent of a particular Rock Type of Interest, or may correspond to discrete features such as faults. -

Newsletter 16

Number 16 March 2019 Price £6.00 Welcome to the 16th edition of the Welsh Stone Forum May 11th: C12th-C19th stonework of the lower Teifi Newsletter. Many thanks to everyone who contributed to Valley this edition of the Newsletter, to the 2018 field programme, Leader: Tim Palmer and the planning of the 2019 programme. Meet:Meet 11.00am, Llandygwydd. (SN 240 436), off the A484 between Newcastle Emlyn and Cardigan Subscriptions We will examine a variety of local and foreign stones, If you have not paid your subscription for 2019, please not all of which are understood. The first stop will be the forward payment to Andrew Haycock (andrew.haycock@ demolished church (with standing font) at the meeting museumwales.ac.uk). If you are able to do this via a bank point. We will then move to the Friends of Friendless transfer then this is very helpful. Churches church at Manordeifi (SN 229 432), assuming repairs following this winter’s flooding have been Data Protection completed. Lunch will be at St Dogmael’s cafe and Museum (SN 164 459), including a trip to a nearby farm to Last year we asked you to complete a form to update see the substantial collection of medieval stonework from the information that we hold about you. This is so we the mid C20th excavations which have not previously comply with data protection legislation (GDPR, General been on show. The final stop will be the C19th church Data Protection Regulations). If any of your details (e.g. with incorporated medieval doorway at Meline (SN 118 address or e-mail) have changed please contact us so we 387), a new Friends of Friendless Churches listing. -

The City of Cardiff Council, County Borough Councils of Bridgend, Caerphilly, Merthyr Tydfil, Rhondda Cynon Taf and the Vale of Glamorgan

THE CITY OF CARDIFF COUNCIL, COUNTY BOROUGH COUNCILS OF BRIDGEND, CAERPHILLY, MERTHYR TYDFIL, RHONDDA CYNON TAF AND THE VALE OF GLAMORGAN AGENDA ITEM NO: 7 THE GLAMORGAN ARCHIVES JOINT COMMITTEE 27 June 2014 REPORT FOR THE PERIOD 1 March – 31 May 2014 REPORT OF: THE GLAMORGAN ARCHIVIST 1. PURPOSE OF REPORT This report describes the work of Glamorgan Archives for the period 1 March to 31 May 2014. 2. BACKGROUND As part of the agreed reporting process the Glamorgan Archivist updates the Joint Committee quarterly on the work and achievements of the service. 3. Members are asked to note the content of this report. 4. ISSUES A. MANAGEMENT OF RESOURCES 1. Staff: establishment Maintain appropriate levels of staff There has been no staff movement during the quarter. From April the Deputy Glamorgan Archivist reduced her hours to 30 a week. Review establishment The manager-led regrading process has been followed for four staff positions in which responsibilities have increased since the original evaluation was completed. The posts are Administrative Officer, Senior Records Officer, Records Assistant and Preservation Assistant. All were in detriment following the single status assessment and comprise 7 members of staff. Applications have been submitted and results are awaited. 1 Develop skill sharing programme During the quarter 44 volunteers and work experience placements have contributed 1917 hours to the work of the Office. Of these 19 came from Cardiff, nine each from the Vale of Glamorgan and Bridgend, four from Rhondda Cynon Taf and three from outside our area: from Newport, Haverfordwest and Catalonia. In addition nine tours have been provided to prospective volunteers and two references were supplied to former volunteers. -

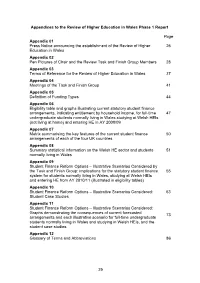

Appendices to the Review of Higher Education in Wales Phase 1 Report

Appendices to the Review of Higher Education in Wales Phase 1 Report Page Appendix 01 Press Notice announcing the establishment of the Review of Higher 26 Education in Wales Appendix 02 Pen Pictures of Chair and the Review Task and Finish Group Members 28 Appendix 03 Terms of Reference for the Review of Higher Education in Wales 37 Appendix 04 Meetings of the Task and Finish Group 41 Appendix 05 Definition of Funding Types 44 Appendix 06 Eligibility table and graphs illustrating current statutory student finance arrangements, indicating entitlement by household income, for full-time 47 undergraduate students normally living in Wales studying at Welsh HEIs (not living at home) and entering HE in AY 2008/09 Appendix 07 Matrix summarising the key features of the current student finance 50 arrangements of each of the four UK countries Appendix 08 Summary statistical information on the Welsh HE sector and students 51 normally living in Wales Appendix 09 Student Finance Reform Options – Illustrative Scenarios Considered by the Task and Finish Group: implications for the statutory student finance 55 system for students normally living in Wales, studying at Welsh HEIs and entering HE from AY 2010/11 (illustrated in eligibility tables) Appendix 10 Student Finance Reform Options – Illustrative Scenarios Considered: 63 Student Case Studies Appendix 11 Student Finance Reform Options – Illustrative Scenarios Considered: Graphs demonstrating the consequences of current forecasted 73 arrangements and each illustrative scenario for full-time undergraduate students normally living in Wales and studying in Welsh HEIs, and the student case studies Appendix 12 Glossary of Terms and Abbreviations 86 25 Appendix 01 Press notice announcing the establishment of the Review of Higher Education in Wales Minister announces Task and Finish group to review higher education in Wales Education Minister Jane Hutt today announced the membership of a Task and Finish group that will conduct a two-stage review of higher education in Wales. -

The Involvement of the Women of the South Wales Coalfield In

“Not Just Supporting But Leading”: The Involvement of the Women of the South Wales Coalfield in the 1984-85 Miners’ Strike By Rebecca Davies Enrolment: 00068411 Thesis submitted for Doctor of Philosophy degree at the University of Glamorgan February 2010. ABSTRACT The 1984-85 miners’ strike dramatically changed the face of the South Wales Valleys. This dissertation will show that the women’s groups that played such a crucial supportive role in it were not the homogenous entity that has often been portrayed. They shared some comparable features with similar groups in English pit villages but there were also qualitative differences between the South Wales groups and their English counterparts and between the different Welsh groups themselves. There is evidence of tensions between the Welsh groups and disputes with the communities they were trying to assist, as well as clashes with local miners’ lodges and the South Wales NUM. At the same time women’s support groups, various in structure and purpose but united in the aim of supporting the miners, challenged and shifted the balance of established gender roles The miners’ strike evokes warm memories of communities bonding together to fight for their survival. This thesis investigates in detail the women involved in support groups to discover what impact their involvement made on their lives afterwards. Their role is contextualised by the long-standing tradition of Welsh women’s involvement in popular politics and industrial disputes; however, not all women discovered a new confidence arising from their involvement. But others did and for them this self-belief survived the strike and, in some cases, permanently altered their own lives. -

PT Conditions in the South Wales Coalfield

Journal of the Geological Society, London, Vol. 153, 1996, pp. 265-275, 10 figs. 2 tables. Printed in Northern Ireland P-T conditions in the South Wales Coalfield: evidence from coexisting hydrocarbon and aqueous fluid inclusions D. H. M. ALDERTON’ & R. E. BEVINS2 I Department of Geology, Royal Holloway (University of London), Egham, Surrey TW20 OEX, UK ’Department of Geology, National Museum of Wales, Cardiff CFl 3NP, UK Abstract: Siderite nodules in the Carboniferous Coal Measures of South Wales contain cavities which are often infilled with quartz, carbonates, sulphides, and hydrocarbons. The quartz contains a mixture of hydrocarbon and aqueous fluid inclusions. The aqueous fluid inclusions consist of a dilute brine (3 wt % NaCl equivalent) and have homogenization temperatures in the range 97-212 “C (mean 143 “C). The hydrocarbon fluid inclusions are dominated by methane with a small component of higher order hydrocarbons;their homogenization temperatures are in therange 35-78°C (mean54°C). It is assumed that the two fluids were trapped simultaneously during growth of the quartz and thus a P-T estimate of entrapment can be obtained by graphical intersection of the hydrocarbon isochores and the aqueous fluid bubble point (homogenization) temperatures assuming hydrocarbon saturation. This method gives temperaturesbetween 130 and160”C, and pressures between 40 and 55 MPa. The timing of mineralization is uncertain, but it is suggested that it took place during burial and low grade metamorphism of the subsiding sedimentary basin (i.e. in the Upper Carboniferous). The hydrother- mal fluids were probably derived from evolved meteoric or connate waters expelled during subsidence and sediment compaction. -

The First City-Wide Map of Shallow Groundwater Temperatures in the UK

1 The first city-wide map of shallow groundwater 2 temperatures in the UK to support the development of 3 ground source heat systems 4 Gareth Farr1, Ashley M. Patton1, David P. Boon1, David R. James2, Bernard Williams2 & David 5 I. Schofield1. 6 1British Geological Survey, Columbus House, Tongwynlais, Cardiff, CF15 7NE, UK 7 2Cardiff Harbour Authority, Queen Alexandra House, Cargo Road, Cardiff Bay, CF10 4LY, UK 8 *Corresponding author (e-mail: [email protected]) 9 10 Keywords: ground source heating, open loop, urban heat island, low enthalpy, Cardiff, Wales. 11 12 Abstract: Low enthalpy ground source heating systems can help to reduce our dependency on fossil 13 fuels, in turn reducing greenhouse gas emissions and increasing energy security. In order to de-risk and 14 support the sustainable development, regulation and management of ground source heating systems in 15 urban areas, detailed baseline mapping of groundwater temperatures is required. Groundwater 16 temperatures were measured in 168 monitoring boreholes primarily within a Quaternary sand and gravel 17 aquifer in the city of Cardiff, UK. The data has been used to create the first city-wide map of shallow 18 groundwater temperatures in the UK. This map can be used both to support development of ground 19 source heating but also to act as a detailed baseline from which to measure change. Shallow groundwater 20 temperatures under the city were found to be 2°C warmer than the UK average groundwater temperature 21 and this additional heat is attributed to the Urban Heat Island. The Zone of Seasonal Fluctuation varies 22 from 7.1 and 15.5 mbgl within the shallow Quaternary aquifer, averaging 9.5 mbgl. -

Draft Sustainability Appraisal Scoping Report Appendix 2

biivi Torfaen Replacement Local Development Plan (2018-2033) Cynllun Datblygu Amnewid Lleol Torfaen (2018-2033) Draft Sustainability Appraisal Scoping Report Adroddiad Drafft Cwmpasu Gwerthusiad Cynaliadwyedd Appendix 2 - Baseline Characteristics of Torfaen Atodiad 2 - Rhynweddau Sylfaenol Torfaen April 2019 Ebrill 2019 TORFAEN COUNTY BOROUGH COUNCIL REPLACEMENT LOCAL DEVELOPMENT PLAN DRAFT SUSTAINABILITY APPRAISAL SCOPING REPORT APPENDIX 2 THE BASELINE CHARACTERISTICS OF TORFAEN April 2019 Front Cover Image Credits Big Pit, Blaenavon - Amgueddfa Cymru – National Museum Wales Cwmbran Town Centre - M&G Retail Draft Sustainability Appraisal Scoping Report 2 Appendix 2 - The Baseline Characteristics of Torfaen (April 2019) Contents 1 Introduction 5 1.1 Introduction 5 2. A Prosperous Wales 6 2.1 Introduction 6 2.2 Employment and Economy 6 2.3 Tourism 18 2.4 Retail 19 2.5 Education 20 2.6 Key Issues 23 2.7 LDP Opportunities 24 3. A Resilient Wales 25 3.1 Introduction 25 3.2 Air 25 3.3 Biodiversity, Flora & Fauna 27 3.4 Water 31 3.5 Geology, Minerals & Soils 35 3.6 Waste 44 3.7 WIMD Physical Environment Domain 48 3.8 Key Issues 48 3.9 LDP Opportunities 50 4. A Healthier Wales 52 4.1 Introduction 52 4.2 Access to Services 52 4.3 Community Facilities & Recreation 53 4.4 Human Health 54 4.5 Key Issues 58 4.6 LDP Opportunities 58 5. A More Equal Wales 59 5.1 Introduction 59 5.2 Population 59 5.3 Key Issues 65 5.4 LDP Opportunities 65 6. A Wales of Cohesive Communities 67 6.1 Introduction 67 6.2 Multiple Deprivation 67 6.3 Housing 69 6.4 Crime 89 6.5 Transport 92 6.6 Key Issues 106 6.7 LDP Opportunities 110 7. -

Valley of Vision

21 January to 19 March 2017 Saturdays and Sundays 3 to 5pm Wolfson Fine Arts in collaboration with the University of South Wales Valley Valley of Vision www.wolfson.cam.ac.uk/fine-arts Foreword - Painting the Valleys is the subject matter. Apart from a scattering of small mines and a few huge, opencast sites on the rim of the coalfield, there is no longer a coal industry. There For over two hundred years, the Valleys of South Wales have inspired are memories and ruins, books, photographs and articles, industrial museums painters and printmakers. J M W Turner, Richard Wilson and Julius Caesar and visitors’ centres. And there are ghosts and paintings. Ibbetson were among the early visitors, drawn to the coalfield by the promise of extraordinary images – the visual combination of burgeoning I know for certain that the ghosts are still out there, haunting abandoned heavy industry and dramatic landscapes. mineshafts, winding-sheds and chapels where the physical evidence of an industry that once employed a quarter of a million miners in these Valleys has They came to witness the fiery spectacle of iron furnaces giving birth to a new almost disappeared. Even the scarred hillsides have been blanketed in new industrial age. Here was the cutting edge of Britain’s pioneering technologies. forests as the Valleys continue to be greened. Yet they discovered, within a stone’s throw of the blast furnaces and pit shafts, a landscape of waterfalls, precipitous forests and wild, romantic moorland. Thankfully, the paintings have survived. Some of them are gathered here, at this exhibition. -

Edging the Estuary

the welsh + Richard Wyn Jones Devolution’s unfinished business John Osmond Theodore Huckle and a Welsh jurisdiction Emrys Roberts Elystan Morgan’s tryst with Wales John Borkowski and Angus Walker Wales should join with West on airport Cynog Dafis Sacred landscape and sustainable development Zoë Harcombe The obesity epidemic Katie Harris Human trafficking on our streets Peter Jones Why a barrage is a step too far Gareth Rees Edging Cultural apartheid on the airwaves Karen Owen When Caernarfon was the print the estuary capital of Wales Trevor Fishlock A hole in our national trouser Nigel Jenkins In the footsteps of Y Gododdin www.iwa.org.uk | Spring 2013 | No. 49 | £8.99 The Institute of Welsh Affairs gratefully acknowledges funding support from the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust, the Esmée Fairbairn Foundation and the Waterloo Foundation. The following organisations are corporate members: Public Sector Private Sector Voluntary Sector • Aberystwyth University • ABACA Limited • Aberdare & District Chamber • ACAS Wales • Arden Kitt Associates Ltd of Trade & Commerce • Bangor University • Association of Chartered Certified • Alcohol Concern Cymru • BBC Cymru Wales Accountants (ACCA) • Business in the Community • Cardiff & Vale College / Coleg Caerdydd a’r Fro • Beaufort Research • Cardiff University (CAIRD) • Cardiff School of Management • BT • Cartrefi Cymru • Cardiff University • Cassidian UK Ltd • Cartrefi Cymunedol Community • Cardiff University Library • Castell Howell Foods Housing Cymru • Centre for Regeneration Excellence Wales • -

Bangor University DOCTOR of PHILOSOPHY the History of the Jewish Diaspora in Wales Parry-Jones

Bangor University DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY The history of the Jewish diaspora in Wales Parry-Jones, Cai Award date: 2014 Awarding institution: Bangor University Link to publication General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 07. Oct. 2021 Contents Abstract ii Acknowledgments iii List of Abbreviations v Map of Jewish communities established in Wales between 1768 and 1996 vii Introduction 1 1. The Growth and Development of Welsh Jewry 36 2. Patterns of Religious and Communal Life in Wales’ Orthodox Jewish 75 Communities 3. Jewish Refugees, Evacuees and the Second World War 123 4. A Tolerant Nation?: An Exploration of Jewish and Non-Jewish Relations 165 in Nineteenth and Twentieth Century Wales 5. Being Jewish in Wales: Exploring Jewish Encounters with Welshness 221 6. The Decline and Endurance of Wales’ Jewish Communities in the 265 Twentieth and Twenty-first Centuries Conclusion 302 Appendix A: Photographs and Etchings of a Number of Wales’ Synagogues 318 Appendix B: Images from Newspapers and Periodicals 331 Appendix C: Figures for the Size of the Communities Drawn from the 332 Jewish Year Book, 1896-2013 Glossary 347 Bibliography 353 i Abstract This thesis examines the history of Jewish communities and individuals in Wales. -

Wales Heritage Interpretation Plan

TOUCH STONE GREAT EXPLANATIONS FOR PEOPLE AT PLACES Cadw Pan-Wales heritage interpretation plan Wales – the first industrial nation Ysgogiad DDrriivviinngg FFoorrcceess © Cadw, Welsh Government Interpretation plan October 2011 Cadw Pan-Wales heritage interpretation plan Wales – the first industrial nation Ysgogiad Driving Forces Interpretation plan Prepared by Touchstone Heritage Management Consultants, Red Kite Environment and Letha Consultancy October 2011 Touchstone Heritage Management Consultants 18 Rose Crescent, Perth PH1 1NS, Scotland +44/0 1738 440111 +44/0 7831 381317 [email protected] www.touchstone-heritage.co.uk Michael Hamish Glen HFAHI FSAScot FTS, Principal Associated practice: QuiteWrite Cadw – Wales – the first industrial nation / Interpretation plan i ____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Contents 1 Foreword 1 2 Introduction 3 3 The story of industry in Wales 4 4 Our approach – a summary 13 5 Stakeholders and initiatives 14 6 Interpretive aim and objectives 16 7 Interpretive themes 18 8 Market and audiences 23 9 Our proposals 27 10 Interpretive mechanisms 30 11 Potential partnerships 34 12 Monitoring and evaluation 35 13 Appendices: Appendix A: Those consulted 38 Appendix B: The brief in full 39 Appendix C: National Trust market segments 41 Appendix D: Selected people and sites 42 The illustration on the cover is part of a reconstruction drawing of Blaenavon Ironworks by Michael