Valley of Vision

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FGV-Newsletter-Summer-2018.Pdf

Painting From Memory The Landscape of Kyffin Williams Angela Hughes John ‘Kyffin’ Williams (1918– relentlessly by the Irish Sea; as Ian Jeffrey (in Sinclair, 2004, 18,) 2006) is one of the most wrote: “Snowdonia is not a biddable terrain in the style of the successful Welsh artists of the English shires”. Therefore, Williams developed a different mode of 20th century, best known for expression, what Nicholas Sinclair (2007, 31) called a “highly painting the people and land- individual language”, to communicate this ancient drama, which scape of Gwynedd and the he argues, separates Williams “from the English landscape low-lying farmland of north- tradition of the previous hundred years.” west Wales. Born and raised in these areas, he came to know A key component in Williams’ visual language is simplification; he the landscape and people strips the composition of everything except its essential elements, intimately and loved them as Alistair Crawford (quoted in Skidmore, 2008, 127) noted passionately. Whilst a student “Kyffin’s landscape is as sparse as a memory from childhood”. in the Slade School of Art, To achieve this uncluttered image, Williams would make sketches London (1941-1944), Williams of a scene using black Indian ink, water colour and soft 4b or 6b was clear that the land and sea pencils, trying to be exact as possible in capturing the essence of his cynefin - the metaphoric of a place, but “never attempted to interpret” at this stage. ‘square mile’ where he felt (Williams, 1973, 158) In his studio, Williams would then re-inter- a sense of belonging, would pret the landscape, discarding typographical accuracy, in favour form the central motif of his of the expressive qualities of mood and drama. -

THE FRY ART GALLERY TOO When Bardfield Came to Walden Artists in Saffron Walden from the 1960S to the 1980S 2 December 2017 to 25 March 2018

THE FRY ART GALLERY TOO When Bardfield Came to Walden Artists in Saffron Walden from the 1960s to the 1980s 2 December 2017 to 25 March 2018 Welcome to our new display space - The Fry Art Gallery Too - which opens for the first time while our main gallery at 19a Castle Street undergoes its annual winter closure for maintenance and work on the Collection. The north west Essex village of Great Bardfield and its surrounding area became the home for a wide range of artists from the early 1930s until the 1980s. More than 3000 examples of their work are brought together in the North West Essex Collection, selections of which are displayed in exhibitions at The Fry Art Gallery. Our first display in our new supplementary space focuses on those artists who lived at various times in and around Saffron Walden in the later twentieth century. Edward and Charlotte Bawden were the first artists to arrive in Great Bardfield around 1930, along with Eric and Tirzah Ravilious. After 30 years at Brick House, Charlotte arranged in 1970 that she and Edward would move to Park Lane, Saffron Walden for their later years. Sadly, Charlotte died before the move, but Edward was welcomed into an established community of successful professional artists in and around the town. These included artists Paul Beck and John Bolam, and the stage designers Olga Lehmann and David Myerscough- Jones. Sheila Robinson had already moved to the town from Great Bardfield in 1968, with her daughter Chloë Cheese, while the writer and artist Olive Cook had been established here with her photographer and artist husband Edwin Smith for many years. -

Wales Regional Geology RWM | Wales Regional Geology

Wales regional geology RWM | Wales Regional Geology Contents 1 Introduction Subregions Wales: summary of the regional geology Available information for this region 2 Rock type Younger sedimentary rocks Older sedimentary rocks 3 Basement rocks Rock structure 4 Groundwater 5 Resources 6 Natural processes Further information 7 - 21 Figures 22 - 24 Glossary Clicking on words in green, such as sedimentary or lava will take the reader to a brief non-technical explanation of that word in the Glossary section. By clicking on the highlighted word in the Glossary, the reader will be taken back to the page they were on. Clicking on words in blue, such as Higher Strength Rock or groundwater will take the reader to a brief talking head video or animation providing a non-technical explanation. For the purposes of this work the BGS only used data which was publicly available at the end of February 2016. The one exception to this was the extent of Oil and Gas Authority licensing which was updated to include data to the end of June 2018. 1 RWM | Wales Regional Geology Introduction This region comprises Wales and includes the adjacent inshore area which extends to 20km from the coast. Subregions To present the conclusions of our work in a concise and accessible way, we have divided Wales into 6 subregions (see Figure 1 below). We have selected subregions with broadly similar geological attributes relevant to the safety of a GDF, although there is still considerable variability in each subregion. The boundaries between subregions may locally coincide with the extent of a particular Rock Type of Interest, or may correspond to discrete features such as faults. -

Energy in Wales

House of Commons Welsh Affairs Committee Energy in Wales Third Report of Session 2005–06 Volume I Report, together with formal minutes, Ordered by The House of Commons to be printed 11 July 2006 HC 876-I Published on Thursday 20 July 2006 by authority of the House of Commons London: The Stationery Office Limited £0.00 The Welsh Affairs Committee The Welsh Affairs Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to examine the expenditure, administration, and policy of the Office of the Secretary of State for Wales (including relations with the National Assembly for Wales.) Current membership Dr Hywel Francis MP (Chairman) (Labour, Aberavon) Mr Stephen Crabb MP (Conservative, Preseli Pembrokeshire) David T. C. Davies MP (Conservative, Monmouth) Nia Griffith MP (Labour, Llanelli) Mrs Siân C. James MP (Labour, Swansea East) Mr David Jones MP (Conservative, Clwyd West) Mr Martyn Jones MP (Labour, Clwyd South) Albert Owen MP (Labour, Ynys Môn) Jessica Morden MP (Labour, Newport East) Hywel Williams MP (Plaid Cymru, Caernarfon) Mark Williams MP (Liberal Democrat, Ceredigion) Powers The Committee is one of the departmental select committees, the powers of which are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No 152. These are available on the Internet via www.parliament.uk. Publications The Reports and evidence of the Committee are published by The Stationery Office by Order of the House. All publications of the Committee (including press notices) are on the Internet at www.parliament.uk/parliamentary_committees/welsh_affairs_committee.cfm. A list of Reports of the Committee in the present Parliament is at the back of this volume. -

Newsletter 16

Number 16 March 2019 Price £6.00 Welcome to the 16th edition of the Welsh Stone Forum May 11th: C12th-C19th stonework of the lower Teifi Newsletter. Many thanks to everyone who contributed to Valley this edition of the Newsletter, to the 2018 field programme, Leader: Tim Palmer and the planning of the 2019 programme. Meet:Meet 11.00am, Llandygwydd. (SN 240 436), off the A484 between Newcastle Emlyn and Cardigan Subscriptions We will examine a variety of local and foreign stones, If you have not paid your subscription for 2019, please not all of which are understood. The first stop will be the forward payment to Andrew Haycock (andrew.haycock@ demolished church (with standing font) at the meeting museumwales.ac.uk). If you are able to do this via a bank point. We will then move to the Friends of Friendless transfer then this is very helpful. Churches church at Manordeifi (SN 229 432), assuming repairs following this winter’s flooding have been Data Protection completed. Lunch will be at St Dogmael’s cafe and Museum (SN 164 459), including a trip to a nearby farm to Last year we asked you to complete a form to update see the substantial collection of medieval stonework from the information that we hold about you. This is so we the mid C20th excavations which have not previously comply with data protection legislation (GDPR, General been on show. The final stop will be the C19th church Data Protection Regulations). If any of your details (e.g. with incorporated medieval doorway at Meline (SN 118 address or e-mail) have changed please contact us so we 387), a new Friends of Friendless Churches listing. -

The Social Identity of Wales in Question: an Analysis of Culture, Language, and Identity in Cardiff, Bangor, and Aberystwyth

Linfield University DigitalCommons@Linfield Fulbright Grantee Projects Office of Competitive Scholarships 8-3-2012 The Social Identity of Wales in Question: An Analysis of Culture, Language, and Identity in Cardiff, Bangor, and Aberystwyth Clara Martinez Linfield College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.linfield.edu/fulbright Part of the Critical and Cultural Studies Commons, and the International and Intercultural Communication Commons Recommended Citation Martinez, Clara, "The Social Identity of Wales in Question: An Analysis of Culture, Language, and Identity in Cardiff, Bangor, and Aberystwyth" (2012). Fulbright Grantee Projects. Article. Submission 4. https://digitalcommons.linfield.edu/fulbright/4 This Article is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It is brought to you for free via open access, courtesy of DigitalCommons@Linfield, with permission from the rights-holder(s). Your use of this Article must comply with the Terms of Use for material posted in DigitalCommons@Linfield, or with other stated terms (such as a Creative Commons license) indicated in the record and/or on the work itself. For more information, or if you have questions about permitted uses, please contact [email protected]. Fulbright Summer Institute: Wales 2012 The Social Identity of Wales in Question: An Analysis of Culture, Language, and Identity in Cardiff, Bangor, and Aberystwyth Clara Martinez Reflective Journal Portfolio Fulbright Wales Summer Institute Professors August 3, 2012 Table of Contents Introduction -

The City of Cardiff Council, County Borough Councils of Bridgend, Caerphilly, Merthyr Tydfil, Rhondda Cynon Taf and the Vale of Glamorgan

THE CITY OF CARDIFF COUNCIL, COUNTY BOROUGH COUNCILS OF BRIDGEND, CAERPHILLY, MERTHYR TYDFIL, RHONDDA CYNON TAF AND THE VALE OF GLAMORGAN AGENDA ITEM NO: 7 THE GLAMORGAN ARCHIVES JOINT COMMITTEE 27 June 2014 REPORT FOR THE PERIOD 1 March – 31 May 2014 REPORT OF: THE GLAMORGAN ARCHIVIST 1. PURPOSE OF REPORT This report describes the work of Glamorgan Archives for the period 1 March to 31 May 2014. 2. BACKGROUND As part of the agreed reporting process the Glamorgan Archivist updates the Joint Committee quarterly on the work and achievements of the service. 3. Members are asked to note the content of this report. 4. ISSUES A. MANAGEMENT OF RESOURCES 1. Staff: establishment Maintain appropriate levels of staff There has been no staff movement during the quarter. From April the Deputy Glamorgan Archivist reduced her hours to 30 a week. Review establishment The manager-led regrading process has been followed for four staff positions in which responsibilities have increased since the original evaluation was completed. The posts are Administrative Officer, Senior Records Officer, Records Assistant and Preservation Assistant. All were in detriment following the single status assessment and comprise 7 members of staff. Applications have been submitted and results are awaited. 1 Develop skill sharing programme During the quarter 44 volunteers and work experience placements have contributed 1917 hours to the work of the Office. Of these 19 came from Cardiff, nine each from the Vale of Glamorgan and Bridgend, four from Rhondda Cynon Taf and three from outside our area: from Newport, Haverfordwest and Catalonia. In addition nine tours have been provided to prospective volunteers and two references were supplied to former volunteers. -

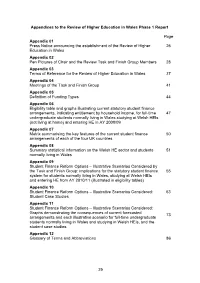

Appendices to the Review of Higher Education in Wales Phase 1 Report

Appendices to the Review of Higher Education in Wales Phase 1 Report Page Appendix 01 Press Notice announcing the establishment of the Review of Higher 26 Education in Wales Appendix 02 Pen Pictures of Chair and the Review Task and Finish Group Members 28 Appendix 03 Terms of Reference for the Review of Higher Education in Wales 37 Appendix 04 Meetings of the Task and Finish Group 41 Appendix 05 Definition of Funding Types 44 Appendix 06 Eligibility table and graphs illustrating current statutory student finance arrangements, indicating entitlement by household income, for full-time 47 undergraduate students normally living in Wales studying at Welsh HEIs (not living at home) and entering HE in AY 2008/09 Appendix 07 Matrix summarising the key features of the current student finance 50 arrangements of each of the four UK countries Appendix 08 Summary statistical information on the Welsh HE sector and students 51 normally living in Wales Appendix 09 Student Finance Reform Options – Illustrative Scenarios Considered by the Task and Finish Group: implications for the statutory student finance 55 system for students normally living in Wales, studying at Welsh HEIs and entering HE from AY 2010/11 (illustrated in eligibility tables) Appendix 10 Student Finance Reform Options – Illustrative Scenarios Considered: 63 Student Case Studies Appendix 11 Student Finance Reform Options – Illustrative Scenarios Considered: Graphs demonstrating the consequences of current forecasted 73 arrangements and each illustrative scenario for full-time undergraduate students normally living in Wales and studying in Welsh HEIs, and the student case studies Appendix 12 Glossary of Terms and Abbreviations 86 25 Appendix 01 Press notice announcing the establishment of the Review of Higher Education in Wales Minister announces Task and Finish group to review higher education in Wales Education Minister Jane Hutt today announced the membership of a Task and Finish group that will conduct a two-stage review of higher education in Wales. -

The Involvement of the Women of the South Wales Coalfield In

“Not Just Supporting But Leading”: The Involvement of the Women of the South Wales Coalfield in the 1984-85 Miners’ Strike By Rebecca Davies Enrolment: 00068411 Thesis submitted for Doctor of Philosophy degree at the University of Glamorgan February 2010. ABSTRACT The 1984-85 miners’ strike dramatically changed the face of the South Wales Valleys. This dissertation will show that the women’s groups that played such a crucial supportive role in it were not the homogenous entity that has often been portrayed. They shared some comparable features with similar groups in English pit villages but there were also qualitative differences between the South Wales groups and their English counterparts and between the different Welsh groups themselves. There is evidence of tensions between the Welsh groups and disputes with the communities they were trying to assist, as well as clashes with local miners’ lodges and the South Wales NUM. At the same time women’s support groups, various in structure and purpose but united in the aim of supporting the miners, challenged and shifted the balance of established gender roles The miners’ strike evokes warm memories of communities bonding together to fight for their survival. This thesis investigates in detail the women involved in support groups to discover what impact their involvement made on their lives afterwards. Their role is contextualised by the long-standing tradition of Welsh women’s involvement in popular politics and industrial disputes; however, not all women discovered a new confidence arising from their involvement. But others did and for them this self-belief survived the strike and, in some cases, permanently altered their own lives. -

Curwen 2017 Course Brochure

Curwen Print Study Centre Curwen Print Study Centre Fine Art Registered Charity Number1048580 Print For more information Contact 892380 [email protected] Courses Curwen Print Study Centre Chilford Hall Linton CB21 4LE www.curwenprintstudy.co.uk 2017 INTRODUCTION Who we are The Curwen Print Study Centre was established as an educational Fine Art Printmaking charity in the late 1990s by Master Printer Stanley Jones MBE and local entrepreneur and art lover Sam Alper OBE. Since its formation, the Curwen Print Study Centre has established a reputation for excellence in its field. The adult course programme offers something for everyone, from those who are new to printmaking to those who have previous experience and are looking for advanced or Masterclass tuition. Open access is available to artists who have successfully completed the relevant course. We welcome artists of all abilities and all ages. Our highly successful education programme involves school students from Cambridgeshire, Essex, Norfolk, Suffolk, Berkshire, Buckinghamshire and Hertfordshire. The majority of schools re-book each year, encouraged by the higher grades that they subsequently achieve at GCSE, AVCE, IB, AS and A2. The content can be adapted to suit all ability levels, from the least able to the most talented students looking for enrichment and extension. Why choose Curwen? • Experienced tutors • Well-equipped, light and airy studio • Small class sizes • High level of individual support • Welcoming and friendly atmosphere • Tranquil location with plenty -

Oral History and Mining Heritage in Wales and Cornwall

Heritage and Memory: Oral History and Mining Heritage in Wales and Cornwall Submitted by Bethan Elinor Coupland, to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History, December, 2012. This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. (Signature) ..................................................................................... 1 Abstract Scholarly work on the relationship between heritage and memory has largely neglected living memory (that is ‘everyday’ memories of lived experience). There is a common assumption that heritage fosters or maintains broader ‘collective’ memories (often referred to as social, public or cultural memories) in a linear sense, after living memory has lapsed. However, given the range of complex conceptualisations of ‘memory’ itself, there are inevitably multiple ways in which memory and heritage interact. This thesis argues that where heritage displays represent the recent past, the picture is more complex; that heritage narratives play a prominent role in the tussle between different layers of memory. Empirically, the research focuses on two prominent mining heritage sites; Big Pit coal mine in south Wales and Geevor tin mine in Cornwall. Industrial heritage sites are one of the few sorts of public historical representation where heritage narratives exist so closely alongside living memories of the social experiences they represent. -

Download Publication

Arts Council OF GREAT BRITAI N Patronage and Responsibility Thirty=fourth annual report and accounts 1978/79 ARTS COUNCIL OF GREAT BRITAIN REFERENCE ONLY DO NOT REMOVE fROwI THE LIBRARY Thirty-fourth Annual Report and Accounts 1979 ISSN 0066-813 3 Published by the Arts Council of Great Britai n 105 Piccadilly, London W 1V OAU Designed by Duncan Firt h Printed by Watmoughs Limited, Idle, Bradford ; and London Cover pictures : Dave Atkins (the Foreman) and Liz Robertson (Eliza) in the Leicester Haymarket production ofMy Fair Lady, produced by Cameron Mackintosh with special funds from Arts Council Touring (photo : Donald Cooper), and Ian McKellen (Prozorov) and Susan Trac y (Natalya) in the Royal Shakespeare Company's small- scale tour of The Three Sisters . Contents 4 Chairman's Introductio n 5 Secretary-General's Report 12 Regional Developmen t 13 Drama 16 Music and Dance 20 Visual Arts 24 Literature 25 Touring 27 Festivals 27 Arts Centres 28 Community Art s 29 Performance Art 29 Ethnic Arts 30 Marketing 30 Housing the Arts 31 Training 31 Education 32 Research and Informatio n 33 Press Office 33 Publications 34 Scotland 36 Wales 38 Membership of Council and Staff 39 Council, Committees and Panels 47 Annual Accounts , Awards, Funds and Exhibitions The objects for which the Arts Council of Great Britain is established by Royal Charter are : 1 To develop and improve the knowledge , understanding and practice of the arts ; 2 To increase the accessibility of the arts to the public throughout Great Britain ; and 3 To co-operate with government departments, local authorities and other bodies to achieve these objects .