Class, Work and Masculinity in the South Wales Coalfield

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hirwaun Village Study

HIRWAUN VILLAGE STUDY Prepared on behalf of Rhondda Cynon Taf County Borough Council April 2008 Nathaniel Lichfield & Partners Ltd 1st Floor, Westville House Fitzalan Court Cardiff CF24 0EL Offices also in: T 029 2043 5880 Manchester F 029 2049 4081 London E [email protected] Newcastle-upon-Tyne www.nlpplanning.com CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .........................................................................................................3 Introduction...................................................................................................................3 Current supply of public facilities ..................................................................................3 The Vision for Hirwaun .................................................................................................4 Future Elements within Hirwaun ...................................................................................4 Conclusions ..................................................................................................................5 1.0 INTRODUCTION ..........................................................................................................6 Aims and objectives of the study ..................................................................................6 Overview of methodology .............................................................................................8 Structure of study..........................................................................................................9 2.0 -

Maerdy, Ferndale and Blaenllechau

Community Profile – Maerdy, Ferndale and Blaenllechau Version 6 – will be updated and reviewed next on 29.05.20 Maerdy Miners Memorial to commemorate the mining history in the Rhondda is Ferndale high street. situated alongside the A4233 in Maerdy on the way to Aberdare Ferndale is a small town in the Rhondda Fach valley. Its neighboring villages include Maerdy and Blaenllechau. Ferndale is 2.1 miles from Maerdy. It is situated at the top at the Rhondda Fach valley, 8 miles from Pontypridd and 20 miles from Cardiff. The villages have magnificent scenery. Maerdy was the last deep mine in the Rhondda valley and closed in 1985 but the mine was still used to transport men into the mine for coal to be mined to the surface at Tower Colliery until 1990. The population of the area is 7,255 of this 21% is aged over 65 years of age, 18% are aged under 14 and 61% aged 35-50. Most of the population is of working age. 30% of people aged between 16-74 are in full time employment in Maerdy and Ferndale compared with 36% across Wales. 40% of people have no qualifications in Maerdy & Ferndale compared with 26% across Wales (Census, 2011). There is a variety of community facilities offering a variety of activities for all ages. There are local community buildings that people access for activities. These are the Maerdy hub and the Arts Factory. Both centre’s offer job clubs, Citizen’s Advice Bureau (CAB) and signposting. There is a sports centre offering football, netball rugby, Pen y Cymoedd Community Profile – Maerdy and Ferndale/V6/02.09.2019 basketball, tennis and a gym. -

Aberaman, Godreaman, Cwmaman and Abercwmboi

Community Profile – Aberaman, Godreaman, Cwmaman and Abercwmboi Aberaman is a village near Aberdare in the county borough of Rhondda Cynon Taf. It was heavily dependent on the coal industry and the population, as a result, grew rapidly in the late nineteenth century. Most of the industry has now disappeared and a substantial proportion of the working population travel to work in Cardiff. Within the area of Aberaman lies three smaller villages Godreaman, Cwmaman and Abercwmboi. The border of Aberaman runs down the Cynon River. Cwmaman sandstone for climbing sports Cwmaman is a former coal mining village near Aberdare. The name is Welsh for Aman Valley and the River Aman flows through the village. It lies in the valley of several mountains. Within the village, there are two children's playgrounds and playing fields. At the top of the village there are several reservoirs accessible from several footpaths along the river. Cwmaman Working Men’s club was the first venue the band the Stereophonics played from, the band were all from the area. Cwmaman is the venue for an annual music festival which has been held Abercwmboi RFC a community every year since 2008 on the last weekend of September. venue for functions. Abercwmboi has retained its identity and not been developed as have many other Cynon Valley villages. As a result, is a very close and friendly community. Many families continue to remain within the community and have a great sense of belonging. Abercwmboi RFC offer a venue for community functions and have teams supporting junior rugby, senior rugby and women’s rugby. -

Rhondda Cynon Taf Christmas 2019 & New Year Services 2020

Rhondda Cynon Taf Christmas 2019 & New Year Services 2020 Christmas Christmas Service Days of Sunday Monday Boxing Day Friday Saturday Sunday Monday New Year's Eve New Year's Day Thursday Operators Route Eve Day number Operation 22 / 12 / 19 23 / 12 / 19 26 / 12 / 19 27 / 12 / 19 28 / 12 / 19 29 / 12 / 19 30 / 12 / 19 31 / 12 / 19 01 / 01 / 20 02 / 01 / 20 24 / 12 / 19 25 / 12 / 19 School School School Mon to Sat Saturday Normal Saturday Saturday Stagecoach 1 Aberdare - Abernant No Service Holiday Holiday No Service No Service No Service No Service Holiday (Daytime) Service Service Service Service Service Service Service School School School Mon to Sat Saturday Normal Saturday Saturday Stagecoach 2 Aberdare - Tŷ Fry No Service Holiday Holiday No Service No Service No Service No Service Holiday (Daytime) Service Service Service Service Service Service Service Early Finish Globe Mon to Sat Penrhiwceiber - Cefn Normal Normal Normal Normal Normal Normal 3 No Service No Service No Service No Service (see No Service Coaches (Daytime) Pennar Service Service Service Service Service Service summary) School School School Mon to Sat Aberdare - Llwydcoed - Saturday Normal Saturday Saturday Stagecoach 6 No Service Holiday Holiday No Service No Service No Service No Service Holiday (Daytime) Merthyr Tydfil Service Service Service Service Service Service Service Harris Mon to Sat Normal Normal Saturday Normal Saturday Saturday Normal 7 Pontypridd - Blackwood No Service No Service No Service No Service No Service Coaches (Daytime) Service Service Service -

Wales Regional Geology RWM | Wales Regional Geology

Wales regional geology RWM | Wales Regional Geology Contents 1 Introduction Subregions Wales: summary of the regional geology Available information for this region 2 Rock type Younger sedimentary rocks Older sedimentary rocks 3 Basement rocks Rock structure 4 Groundwater 5 Resources 6 Natural processes Further information 7 - 21 Figures 22 - 24 Glossary Clicking on words in green, such as sedimentary or lava will take the reader to a brief non-technical explanation of that word in the Glossary section. By clicking on the highlighted word in the Glossary, the reader will be taken back to the page they were on. Clicking on words in blue, such as Higher Strength Rock or groundwater will take the reader to a brief talking head video or animation providing a non-technical explanation. For the purposes of this work the BGS only used data which was publicly available at the end of February 2016. The one exception to this was the extent of Oil and Gas Authority licensing which was updated to include data to the end of June 2018. 1 RWM | Wales Regional Geology Introduction This region comprises Wales and includes the adjacent inshore area which extends to 20km from the coast. Subregions To present the conclusions of our work in a concise and accessible way, we have divided Wales into 6 subregions (see Figure 1 below). We have selected subregions with broadly similar geological attributes relevant to the safety of a GDF, although there is still considerable variability in each subregion. The boundaries between subregions may locally coincide with the extent of a particular Rock Type of Interest, or may correspond to discrete features such as faults. -

Newsletter 16

Number 16 March 2019 Price £6.00 Welcome to the 16th edition of the Welsh Stone Forum May 11th: C12th-C19th stonework of the lower Teifi Newsletter. Many thanks to everyone who contributed to Valley this edition of the Newsletter, to the 2018 field programme, Leader: Tim Palmer and the planning of the 2019 programme. Meet:Meet 11.00am, Llandygwydd. (SN 240 436), off the A484 between Newcastle Emlyn and Cardigan Subscriptions We will examine a variety of local and foreign stones, If you have not paid your subscription for 2019, please not all of which are understood. The first stop will be the forward payment to Andrew Haycock (andrew.haycock@ demolished church (with standing font) at the meeting museumwales.ac.uk). If you are able to do this via a bank point. We will then move to the Friends of Friendless transfer then this is very helpful. Churches church at Manordeifi (SN 229 432), assuming repairs following this winter’s flooding have been Data Protection completed. Lunch will be at St Dogmael’s cafe and Museum (SN 164 459), including a trip to a nearby farm to Last year we asked you to complete a form to update see the substantial collection of medieval stonework from the information that we hold about you. This is so we the mid C20th excavations which have not previously comply with data protection legislation (GDPR, General been on show. The final stop will be the C19th church Data Protection Regulations). If any of your details (e.g. with incorporated medieval doorway at Meline (SN 118 address or e-mail) have changed please contact us so we 387), a new Friends of Friendless Churches listing. -

Starting School 2018-19 Cover Final.Qxp Layout 1

Starting School 2018-2019 Contents Introduction 2 Information and advice - Contact details..............................................................................................2 Part 1 3 Primary and Secondary Education – General Admission Arrangements A. Choosing a School..........................................................................................................................3 B. Applying for a place ........................................................................................................................4 C.How places are allocated ................................................................................................................5 Part 2 7 Stages of Education Maintained Schools ............................................................................................................................7 Admission Timetable 2018 - 2019 Academic Year ............................................................................14 Admission Policies Voluntary Aided and Controlled (Church) Schools ................................................15 Special Educational Needs ................................................................................................................24 Part 3 26 Appeals Process ..............................................................................................................................26 Part 4 29 Provision of Home to School/College Transport Learner Travel Policy, Information and Arrangements ........................................................................29 -

The Pit and the Pendulum: a Cooperative Future for Work in The

Pit and the Pendulum Prelims.qxd 02/03/04 13:34 Page i POLITICS AND SOCIETY IN WALES The Pit and the Pendulum Pit and the Pendulum Prelims.qxd 02/03/04 13:34 Page ii POLITICS AND SOCIETY IN WALES SERIES Series editor: Ralph Fevre Previous volumes in the series: Paul Chaney, Tom Hall and Andrew Pithouse (eds), New Governance – New Democracy? Post-Devolution Wales Neil Selwyn and Stephen Gorard, The Information Age: Technology, Learning and Exclusion in Wales Graham Day, Making Sense of Wales: A Sociological Perspective Richard Rawlings, Delineating Wales: Constitutional, Legal and Administrative Aspects of National Devolution The Politics and Society in Wales Series examines issues of politics and government, and particularly the effects of devolution on policy-making and implementation, and the way in which Wales is governed as the National Assembly gains in maturity. It will also increase our knowledge and understanding of Welsh society and analyse the most important aspects of social and economic change in Wales. Where necessary, studies in the series will incorporate strong comparative elements which will allow a more fully informed appraisal of the condition of Wales. Pit and the Pendulum Prelims.qxd 02/03/04 13:34 Page iii POLITICS AND SOCIETY IN WALES The Pit and the Pendulum A COOPERATIVE FUTURE FOR WORK IN THE WELSH VALLEYS By MOLLY SCOTT CATO Published on behalf of the Social Science Committee of the Board of Celtic Studies of the University of Wales UNIVERSITY OF WALES PRESS CARDIFF 2004 Pit and the Pendulum Prelims.qxd 04/03/04 16:01 Page iv © Molly Scott Cato, 2004 British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data. -

Postal Sector Council Alternative Sector Name Month (Dates)

POSTAL COUNCIL ALTERNATIVE SECTOR NAME MONTH (DATES) SECTOR BN15 0 Adur District Council Sompting, Coombes 02.12.20-03.01.21(excl Christmas holidays) BN15 8 Adur District Council Lancing (Incl Sompting (South)) 02.12.20-03.01.21(excl Christmas holidays) BN15 9 Adur District Council Lancing (Incl Sompting (North)) 02.12.20-03.01.21(excl Christmas holidays) BN42 4 Adur District Council Southwick 02.12.20-03.01.21(excl Christmas holidays) BN43 5 Adur District Council Old Shoreham, Shoreham 02.12.20-03.01.21(excl Christmas holidays) BN43 6 Adur District Council Kingston By Sea, Shoreham-by-sea 02.12.20-03.01.21(excl Christmas holidays) BN12 5 Arun District Council Ferring, Goring-by-sea 02.12.20-03.01.21(excl Christmas holidays) BN16 1 Arun District Council East Preston 02.12.20-03.01.21(excl Christmas holidays) BN16 2 Arun District Council Rustington (South), Brighton 02.12.20-03.01.21(excl Christmas holidays) BN16 3 Arun District Council Rustington, Brighton 02.12.20-03.01.21(excl Christmas holidays) BN16 4 Arun District Council Angmering 02.12.20-03.01.21(excl Christmas holidays) BN17 5 Arun District Council Littlehampton (Incl Climping) 02.12.20-03.01.21(excl Christmas holidays) BN17 6 Arun District Council Littlehampton (Incl Wick) 02.12.20-03.01.21(excl Christmas holidays) BN17 7 Arun District Council Wick, Lyminster 02.12.20-03.01.21(excl Christmas holidays) BN18 0 Arun District Council Yapton, Walberton, Ford, Fontwell 02.12.20-03.01.21(excl Christmas holidays) BN18 9 Arun District Council Arundel (Incl Amberley, Poling, Warningcamp) -

The City of Cardiff Council, County Borough Councils of Bridgend, Caerphilly, Merthyr Tydfil, Rhondda Cynon Taf and the Vale of Glamorgan

THE CITY OF CARDIFF COUNCIL, COUNTY BOROUGH COUNCILS OF BRIDGEND, CAERPHILLY, MERTHYR TYDFIL, RHONDDA CYNON TAF AND THE VALE OF GLAMORGAN AGENDA ITEM NO: 7 THE GLAMORGAN ARCHIVES JOINT COMMITTEE 27 June 2014 REPORT FOR THE PERIOD 1 March – 31 May 2014 REPORT OF: THE GLAMORGAN ARCHIVIST 1. PURPOSE OF REPORT This report describes the work of Glamorgan Archives for the period 1 March to 31 May 2014. 2. BACKGROUND As part of the agreed reporting process the Glamorgan Archivist updates the Joint Committee quarterly on the work and achievements of the service. 3. Members are asked to note the content of this report. 4. ISSUES A. MANAGEMENT OF RESOURCES 1. Staff: establishment Maintain appropriate levels of staff There has been no staff movement during the quarter. From April the Deputy Glamorgan Archivist reduced her hours to 30 a week. Review establishment The manager-led regrading process has been followed for four staff positions in which responsibilities have increased since the original evaluation was completed. The posts are Administrative Officer, Senior Records Officer, Records Assistant and Preservation Assistant. All were in detriment following the single status assessment and comprise 7 members of staff. Applications have been submitted and results are awaited. 1 Develop skill sharing programme During the quarter 44 volunteers and work experience placements have contributed 1917 hours to the work of the Office. Of these 19 came from Cardiff, nine each from the Vale of Glamorgan and Bridgend, four from Rhondda Cynon Taf and three from outside our area: from Newport, Haverfordwest and Catalonia. In addition nine tours have been provided to prospective volunteers and two references were supplied to former volunteers. -

COMMUNITY COORDINATOR BULLETIN March 2018

COMMUNITY COORDINATOR BULLETIN March 2018 CONTENTS Rhondda Valleys Page no. 2 Cynon Valley 4 Taff Ely 5 Merthyr Tydfil 6 Health 7 Cwm Taf general information 8 1 Rhondda Valleys Contact: Meriel Gough Tel: 07580 865938 or email: [email protected] Seasons Dance Spring Sequence Dance th Tuesday 6 March 2-4pm, NUM Tonypandy, Llwynypia Rd. Live music with an organist. Bar will be open for light refreshments. Entry £2. Everyone Welcome. Contact Lynda: 07927 038 922 Over 50’s Walking Group Maerdy Every Thursday from 10:30am – 12:30pm at Teify House, Station Terrace, Maerdy, Ferndale, CF43 4BE You’re sure of a friendly welcome! To find out more call 0800 161 5780 or email [email protected] Walking Football Programme in Clydach Vale This is a new programme: The group meet at 11am until noon every Tuesday at the 3G pitch Clydach Vale.Qualified Coaches oversee the group. Everyone welcome! The first three visits are free and then £2 each thereafter. Contact Cori Williams 01443 442743 / 07791 038918 email: [email protected] Actif Woods Treherbert: Come and try out some woodland activities for FREE! 12-week woodland activity programmes in the Treherbert/RCT area. sessions are run by Woodland Leaders and activities are for Carers and people aged 54+ Come and try out some woodland activities, learn new skills, meet new people and see how woodlands can benefit you! Woodland activities range from short, easy walks, woodland crafts to basic bushcraft skills and woodland management. All activities will be tailored to suit the abilities and needs of the group. -

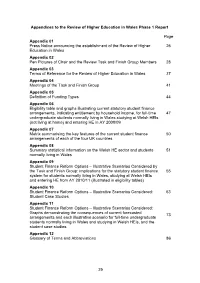

Appendices to the Review of Higher Education in Wales Phase 1 Report

Appendices to the Review of Higher Education in Wales Phase 1 Report Page Appendix 01 Press Notice announcing the establishment of the Review of Higher 26 Education in Wales Appendix 02 Pen Pictures of Chair and the Review Task and Finish Group Members 28 Appendix 03 Terms of Reference for the Review of Higher Education in Wales 37 Appendix 04 Meetings of the Task and Finish Group 41 Appendix 05 Definition of Funding Types 44 Appendix 06 Eligibility table and graphs illustrating current statutory student finance arrangements, indicating entitlement by household income, for full-time 47 undergraduate students normally living in Wales studying at Welsh HEIs (not living at home) and entering HE in AY 2008/09 Appendix 07 Matrix summarising the key features of the current student finance 50 arrangements of each of the four UK countries Appendix 08 Summary statistical information on the Welsh HE sector and students 51 normally living in Wales Appendix 09 Student Finance Reform Options – Illustrative Scenarios Considered by the Task and Finish Group: implications for the statutory student finance 55 system for students normally living in Wales, studying at Welsh HEIs and entering HE from AY 2010/11 (illustrated in eligibility tables) Appendix 10 Student Finance Reform Options – Illustrative Scenarios Considered: 63 Student Case Studies Appendix 11 Student Finance Reform Options – Illustrative Scenarios Considered: Graphs demonstrating the consequences of current forecasted 73 arrangements and each illustrative scenario for full-time undergraduate students normally living in Wales and studying in Welsh HEIs, and the student case studies Appendix 12 Glossary of Terms and Abbreviations 86 25 Appendix 01 Press notice announcing the establishment of the Review of Higher Education in Wales Minister announces Task and Finish group to review higher education in Wales Education Minister Jane Hutt today announced the membership of a Task and Finish group that will conduct a two-stage review of higher education in Wales.