WARREN HITZIG, ALISON MYRDEN, ) Alan N

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vlambaram-Front

kndeVn> ∫t>t tMu> Etu> Vzm>prm>TM • VLAMBARAM TM Canada’s Oldest Tamil Newspaper kw;Wk; midj;Jmidj;J thfd rl;lg;gpur;ridfSf;Fk;l;lgg;gpur;ridfSf;Fk; VINOTHKUMARINOTHKUMAR LICENSEDLICENSED PARALEGALPARALEGAL 647.667.6034647.6667.6037.603344 WWW.TRAFFICKUMAR.CAWWW.TRAFFICKUMAR.CA fT: 28 pelm>: 12 s∫k Ân˘Wnq>qÖpt>TRik metM‰Âiq Elvsm> JUNE 15, 2018 oñreRWye Âtõv› dk>lá ÆWpe›d>! 2018 §ñ 07Eõ fidwpq>q oñreRWye ∏Ty jnfeykk>kd>S Et>Wt›tLõ mekext>Tñ 42Avˇ wpeˇt>Wt›tLõ ErÑdevˇ aTØDy AsnÉkzek mekexm> ¯vˇm> …z>z 124 wteT 40IÖ wpq>Œ oñreRWye fede¸ kZõ 76 AsnÉkizÖ wpq>Œ puim mñqt>Tõ …t>TWyek º›vmen åT›k> vetk>kd>S oñreRWye mekext>Tõ kdS> AKqˇ. akk> dS> Yñ tilVyen wp‰m>peñim Ad>Siy aimk>Kqˇ. 53 vyten Andrea Horwath oñreRWye ak>kd>SYñ tilvren 53 vyˇ fede¸mñqt>Tõ åT›k>kd>St> tilV dk>lá ÆWpe›d> oñreRWye AKqe›. 1990Eõ oñreRWye mekext>Tñ aÎt>t ÂtõvrekÖ mekext>Tõ ∏Ty jnfeykk>kd>S ptVWyq>Kqe›. Ad>S aimt>tˇ. atñ Pñn› Em>Âiqteñ ∏Ty jnfeykk> kd>S awmRk>keVõ Pqf>t 49 vyten Mike aTk AsnÉkizÖ wpq>Œ Schreiner I tilvrekk> wkeÑd …t>TWyekº›v åT›k>kd>Syek pÍimk>kd>S oñreRWye mekext>Tñ vf>ˇz>zˇ. mekext>Tõ …t>TWyekº›vk>kd>S sRt>TWlWy Âtõ tdivyek o‰vir åñŒ aiuÖptq>m>, kd>S aÒvlkÉ kiz fdt>t ars pxm> wpŒvtq>m> iqf>>tˇ o‰ kd>S 8 AsnÉkiz yetõ wpqQ> ‰kk> WvÑÎm.> oñreRWye Lprõ kd>SYñ 161 v‰dkel sRt>Trt> Tõ Em>ÂiqWy Âtõ Âiqyek …t>TWyekº›vkd>S ån aiuk>m> tikimiy Euf>ˇz>zˇ. -

House of Commons Debates

House of Commons Debates VOLUME 147 Ï NUMBER 094 Ï 2nd SESSION Ï 41st PARLIAMENT OFFICIAL REPORT (HANSARD) Monday, June 2, 2014 Speaker: The Honourable Andrew Scheer CONTENTS (Table of Contents appears at back of this issue.) 5961 HOUSE OF COMMONS Monday, June 2, 2014 The House met at 11 a.m. Hamilton, and which I am on most days when I am back in the constituency. Prayers Despite all of these accomplishments and many more, above all else Lincoln Alexander was a champion of young people. He was convinced that if a society did not take care of its youth, it would have no future. He also knew that education and awareness were PRIVATE MEMBERS' BUSINESS essential in changing society's prejudices and sometimes flawed presuppositions about others. That is why it is so fitting that so many Ï (1105) schools are named after him. He himself had been a young person [English] who sought to make his place in his community so that he could contribute to his country. LINCOLN ALEXANDER DAY ACT Mr. David Sweet (Ancaster—Dundas—Flamborough—West- As a young boy, Lincoln Alexander faced prejudice daily, but his dale, CPC) moved that Bill S-213, An Act respecting Lincoln mother encouraged him to be two or three times as good as everyone Alexander Day, be read the second time and referred to a committee. else, and indeed he was. Lincoln Alexander followed his mother's He said: Mr. Speaker, I was proud to introduce Bill S-213, an act advice and worked hard to overcome poverty and prejudice. -

Core 1..136 Hansard (PRISM::Advent3b2 15.50)

House of Commons Debates VOLUME 146 Ï NUMBER 253 Ï 1st SESSION Ï 41st PARLIAMENT OFFICIAL REPORT (HANSARD) Wednesday, May 22, 2013 Speaker: The Honourable Andrew Scheer CONTENTS (Table of Contents appears at back of this issue.) 16793 HOUSE OF COMMONS Wednesday, May 22, 2013 The House met at 2 p.m. As elected officials, it is our duty to give Canadians a voice; we are accountable to them. Today, I am therefore giving a voice to a constituent who wrote to Prayers me: Since you have been in your position, this is really the first time I have been kept Ï (1405) informed about political issues and decisions being made in Ottawa. [English] I really feel as though I am being asked to do my job as a citizen—to express myself—and not just to go and vote. This really is the first time. The Speaker: It being Wednesday, we will now have the singing of the national anthem, led by the hon. member for Papineau. With this survey I received in the mail, I feel as though someone is listening. I see that you really embrace the NDP's vision to get young people involved. Well [Members sang the national anthem] done! I voted for you, and in no way do I regret it. In return, you are doing a good job. You have earned my trust. You are even motivating me to keep my loved ones STATEMENTS BY MEMBERS informed and to urge them to vote. [English] I have a message for my constituents: you can rest assured that the NDP is here to stand up for democracy and defend your right to be B.C. -

Glebe Report

13Iebe repart September 21, 1990 Vol. 19 No. 8 Provincial Election Wrap-up BY MICHAEL PANKHURST 38.3%. In 1987 the Pro- The minority/majority steep learning curve, de- gressive Conservatives pick- question aside, Gigantes ex- feated candidate Richard In the aftermath of the ed up 10.6% of the riding's pressed delight with the Patten is assessing his stunning NDP victory in the votes. In this election, results. "It's a great thrill future. He is not bitter, recent provincial election, support for new PC candi- and quite a responsibility. however, he has become a bit some of the candidates in date, Alex Burney, slipped We will proceed judiciously." disillusioned with politics. Ottawa Centre were asked to 8.9%. John Gay of the Her feelings, she said, went In his eyes, he and his to reflect on the outcome Family Coalition and Bill from initial disbelief to Liberal colleagues "worked of the election and about Hipwell of the Green Party joy as the reality of the hard" in "very stressful their plans for the future. managed to pick up 2.6% and win sunk in She called the jobs" and did not deserve The election result in 1.8% of the vote respective results both "frightening" the kind of trouncing the Ottawa Centre offered no ly. Support for Indepen- and "exhilarating." electorate laid on them. surprises. Evelyn Gigantes dent candidate John Turmel He feels that people are and Richard Patten were run- plunged from 2% to one half "too quick to criticize" and ning neck and neck, although of one percent of the vote. -

5Dterra Infinity

5dterra infinity. Smoking: L&M menthols mood, Random coding using DevBloodshed. EDEN 3. It only takes one (I)ota of (A)lpha et (O)mega to get to (N)omen (E)st (O)men. 4. Will Bael always remain a King in the body of a frog ? Or will the lips of Skip to content the Crowned Queen of space return the King to Grace ? We shall • Home • 5dTERRA SERENITY GLOBAL COOP by danahorochowski see. http://www.facebook.com/METATRON256 Homework for the 7thfire VAMPIRE BBQ or 8thfire 100,000 to Die at the London Olympics ? // Important X Class 1.1 Solar SIOUX BATCHEWANA Event Information (July 7, Posted on July 17, 2012 2012) // http://www.helioviewer.org/ /// http://www.swpc.noaa.gov/today.htm l#satenv MARdi 07 10 2012 = 4 SOL is going to help MOTHER EArth clean up the VRIL VATICAN VIRUS VAMPIRES with +++++++PHOTONS +++++ MOONday 07 09 2012 = 21 Homework for the 7thfire VAMPIRE = 3 byebuysinhttp://8thfire.biz/byebuysi BBQ or 8thfire SIOUX n.htm BATCHEWANA http://www.facebook.com/META BYE BUY SIN SATURN ATON and TRON256 the SLAVE SYSTEM of LEVAN and LILITH, HELLO SERENITY COOP 1. Can 4 fundamental operations of magick be equated with the modes of BARTER TRADE NETWORK divination ? Turmel: Creditos Barter Clubs are half Argentine Solution - Jct: Isaac Isitan’s The 4 modes of divination are 1) sortiledge 2) automatism 3) illusion and “Money” video on the banking system crash in Argentina in 2000 provides 4) hallucination invaluable footage of the rise of the biggest people barter network on Earth, - using a database like Liber 777, it can be proved that there are natural 7,000,000 members, the Red Global de Trueque network. -

“It's Miller Time!”

Queen’s Park Today – Daily Report February 27, 2020 Quotation of the day “It’s Miller time!” Before his question period query, PC MPPs heckle and cheer NDP MPP Paul Miller, who has only asked a handful of questions since the start of the 42nd parliamentary session. Official Opposition Leader Andrea Horwath suggested that’s “something that [the PCs] do to try to create interesting dynamics in our caucus. I wish the government, instead of playing games like that, could actually take seriously the fact that parents in all ridings are very worried about the cutbacks to education.” Today at Queen’s Park On the schedule Morning debate has been cancelled this morning due to an expected snowstorm. The house convenes at 10:15 a.m. for question period. The government could put forward any of the following bills for afternoon debate: ● Bill 156, Security From Trespass and Protecting Food Safety Act; ● Bill 161, Smarter and Stronger Justice Act; ● Bill 171, Building Transit Faster Act; and ● Bill 175, Connecting People to Home and Community Care Act. Bill 145, Trust in Real Estate Services Act, which reforms the real estate industry, could face a third-reading vote after question period. Two PC backbench bills will be called during private members’ business debates: ● Michael Parsa will move second reading of Bill 173, Ontario Day Act; ● Will Bouma and Robin Martin will move their co-sponsored Bill 168, Combating Antisemitism Act. The bill would require the government to follow the working definition of anti-Semitism adopted by the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (IHRA) in 2016. -

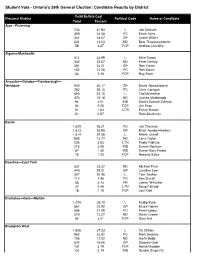

Candidate Results W Late Results

Student Vote - Ontario's 39th General Election: Candidate Results by District Valid Ballots Cast Electoral District Political Code Name of Candidate Total Percent Ajax—Pickering 743 41.93 L Joe Dickson 409 23.08 PC Kevin Ashe 331 18.67 GP Cecile Willert 231 13.03 ND Bala Thavarajasoorier 58 3.27 FCP Andrew Carvalho Algoma-Manitoulin 514 33.99 L Mike Brown 432 28.57 ND Peter Denley 351 23.21 GP Ron Yurick 152 10.05 PC Ron Swain 63 4.16 FCP Ray Scott Ancaster—Dundas—Flamborough— Westdale 940 30.17 GP David Januczkowski 782 25.10 PC Chris Corrigan 690 22.15 L Ted Mcmeekin 473 15.18 ND Juanita Maldonado 94 3.01 IND Martin Samuel Zuliniak 64 2.05 FCP Jim Enos 51 1.63 COR Eileen Butson 21 0.67 Sam Zaslavsky Barrie 1,629 26.21 PC Joe Tascona 1,613 25.95 GP Erich Jacoby-Hawkins 1,514 24.36 L Aileen Carroll 856 13.77 ND Larry Taylor 226 3.63 LTN Paolo Fabrizio 215 3.45 IND Darren Roskam 87 1.39 IND Daniel Gary Predie 75 1.20 FCP Roberto Sales Beaches—East York 531 35.37 ND Michael Prue 440 29.31 GP Caroline Law 307 20.45 L Tom Teahen 112 7.46 PC Don Duvall 56 3.73 FR James Whitaker 37 2.46 LTN Doug Patfield 18 1.19 FCP Joel Kidd Bramalea—Gore—Malton 1,079 38.70 L Kuldip Kular 667 23.92 GP Bruce Haines 588 21.09 PC Pam Hundal 370 13.27 ND Glenn Crowe 84 3.01 FCP Gary Nail Brampton West 1,526 37.23 L Vic Dhillon 962 23.47 PC Mark Beckles 706 17.22 ND Garth Bobb 642 15.66 GP Sanjeev Goel 131 3.19 FCP Norah Madden 131 3.19 IND Gurdial Singh Fiji Brampton—Springdale 1,057 33.95 ND Mani Singh 983 31.57 L Linda Jeffrey 497 15.96 PC Carman Mcclelland -

2009 By-Elections Report

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Elections Canada Report of the Chief Electoral Officer of Canada following the November 9, 2009, by-elections held in Cumberland–Colchester–Musquodoboit Valley, Hochelaga, Montmagny–L’Islet– Kamouraska–Rivière-du-Loup and New Westminster–Coquitlam Text in English and French on inverted pages. ISBN 978-1-100-51213-6 Cat. No.: SE1-2/2009-2 1. Canada. Parliament — Elections, 2009. 2. Elections — British Columbia. 3. Elections — Quebec (Province). 4. Elections — Nova Scotia. I. Title. II. Title: Rapport du directeur général des élections du Canada sur les élections partielles tenues le 9 novembre 2009 dans Cumberland–Colchester–Musquodoboit Valley, Hochelaga, Montmagny–L’Islet–Kamouraska–Rivière-du-Loup et New Westminster–Coquitlam. JL193 E43 2010 324.971'073 C2010-980079-6E © Chief Electoral Officer of Canada, 2010 All rights reserved Printed in Canada For enquiries, please contact: Public Enquiries Unit Elections Canada 257 Slater Street Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0M6 Tel.: 1-800-463-6868 Fax: 1-888-524-1444 (toll-free) TTY: 1-800-361-8935 www.elections.ca March 31, 2010 The Honourable Peter Milliken Speaker of the House of Commons Centre Block House of Commons Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0A6 Dear Mr. Speaker: I have the honour to provide my report following the by-elections, held on November 9, 2009, in the electoral districts of Cumberland–Colchester– Musquodoboit Valley, Hochelaga, Montmagny–L’Islet–Kamouraska–Rivière-du-Loup and New Westminster–Coquitlam. I have prepared the report in accordance with subsection 534(2) of the Canada Elections Act (S.C. 2000, c. 9). Under section 536 of the Act, the Speaker is required to submit this report to the House of Commons without delay. -

7Thfire.Biz NEW PARADIGM Jrgenius International Scools Or

HERSTORY / table of CONTENTs /doc /// pdf// / JAN 7 2013 /// 15 ///21// 31 // / Luna 2013 //// DEC 1 // 7 // 15 // 21 // 31 // / Nov // / October // SEPTEMBER /// /AUGUST // JULY / / JUNO / / MAYDAY // / APRIL FOOLS // MARCH 2012 // AQUARIUS 2012 // JANUS 2012 / Made in cANADa! http://7thfire.biz/01152013.htm FRIADAY 01 11 2013- FREE me in SERENITY 555- JRGENIUS.CA- USURY FREE GLOBAL COOPERATIVE U NITED FISHER KINGDOMS cyberclass.net idlenomore http://cyberclass.net/idlenomore.htm idlenomore http://7thfire.biz/idlenomore.htm IDLE NO MORE idlenomore email list. = January 2013 Email Out - KEEP them ACCOUNTABLE MEEGWETCH DANA EARTH PARTY WALKOUT of your BEAST SLAVE JOB JAN 11 2013. http:// 8thfire .biz/ /// http:// jrgenius .ca/ /// http:// 7thfire .biz/ See you on the STREETS - NAZI FACEBOOK BLOCKED me from SHARING this list with you USURY FREE. PASS it ON.... http://serenitystreetnews.com/119846881-January-2013-Email-Out.pdf //// http://www.scribd.com/doc/119846881/January-2013-Email-Out NEW MOON - PUT your WAMPUM where your MOUTH IS- Today’s new moon in sidereal Sagittarius on January 11, 2013 @ 2:44 PM (EST) is the perfect new moon to begin the year on a “seriously” carefree and optimistic note--as there’s a conjunction with the sidereal sun in 26 degrees of Sagittarius and Mercury in 22 degrees of Sagittarius. A theme of authenticity all wrapped up, in an age old analogy that encourage us to put our money where our mouth is, makes for a good sound resolution. If you think about it, time equals money (at least in our culture) and is also equivalent to our level/s of consciousness. -

Reclaiming the Legislature to Reinvigorate Representative Democracyembargoedcopy

SAMARA’S MP EXIT INTERVIEWS: VOLUME II Flip the Script Reclaiming the legislature to reinvigorate representative democracyEMBARGOEDCOPY REPORT ONE: MPs IN PARLIAMENT REPORT TWO: MPs IN THEIR CONSTITUENCY REPORT THREE: MPs IN THEIR POLITICAL PARTY “If you’ve ever had the misfortune of watching a debate over a piece of legislation … you know that it’s one canned speech followed by another canned speech, where Speaker B makes no attempt to address Speaker A’sEMBARGOED point. They just read from a script with a differentCOPY conclusion.” 2 Contents INTRODUCING SAMARA’S MP EXIT INTERVIEWS: VOLUME II 4 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 6 WHO PARTICIPATED? 8 INTRODUCTION 9 Why start at Parliament? 9 A fire drill with no fire 10 The true work of an MP 11 The job description: MPs on the Hill 11 Constructive dismissal 12 DEBATES AND SCRUTINY: “[WE’RE] BREACHING OUR RESPONSIBILITIES AS PARLIAMENTARIANS” 13 Follow the money—if you can 15 Access to information 15 Tools for the job: Scrutiny 17 COMMITTEES: “JUST SAVE YOUR BREATH” 18 Encroaching partisanship 19 Parliamentary secretaries riding shotgun 20 Musical chairs 23 Busy work for backbenchers? 24 Tools for the job: Committee 25 PRIVATE MEMBERS’ BUSINESS: “TWO HOURS OF GLORY” 26 Duck, duck, goose! 28 Feel-good legislation 29 Taking the long view 30 Tools for the job: Private members’ business 32 CONCLUSION: REINVIGORATING THE PARLIAMENTARY WORK OF MPs 33 Where to start? 33 Empowered representatives, stronger democracy 34 METHODOLOGY 36 END NOTES 37 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 38 PARTICIPATING FORMER MPs 40 3 Introducing Samara’s MP Exit Interviews: Volume II Representative democracy is in trouble. -

Not to Be Forgotten: Care of Vulnerable Canadians

Parliamentary Committee on Palliative and Compassionate Care Not to be Forgotten Care of Vulnerable Canadians Harold Albrecht MP Co chair Joseph Comartin MP Co chair Frank Valeriote MP Co chair Kelly Block MP Francis Scarpaleggia MP Committee Co founders November 2011 Parliamentary Committee on Palliative and Compassionate Care … Special Thanks to Larry Miller MP Bev Shipley MP Pat Davidson MP Gord Brown MP Megan Leslie MP Denise Savoie MP Tim Uppal MP Thanks to the more than 55 MPs, and former MPs, from all parties, who in a multitude of ways, publicly or quietly, supported the Committee’s work. We are grateful to our former Liberal co-chair Michelle Simson for her enthusiasm and hard work. The Committee would especially like to thank the many individuals, organizations and groups who came at their own expense to make these hearings possible. Thank you for all you do on behalf of vulnerable Canadians. ii Table of Contents Executive Summary / 7 Committee Recommendations / 15 Introduction / 18 Part 1: Palliative and End –of-Life Care / 21 I --The Context: The Health Care System and the Care of Vulnerable Persons / 23 II -- The Integrated Continual Care Model / 24 Integrated Continual Care Systems have been shown to be cost effective / 25 III – Palliative Care and an Integrated Care System / 26 IV -- Hierarchy of Care Environments / 28 V -- Medical vs. Community model of care / 29 The role of the federal government / 31 VI -- Recruitment, Capacity building, Media, Education, Research, and Knowledge Translation / 32 Research is vitally needed -

List of Candidates by Electoral District and Individual Results Liste Des Candidats Par Circonscription Et Résultats Individuels

Thirty-seventh general election 2000: TABLE 12/TABLEAU 12 Trente-septième élection générale 2000 : Official voting results Résultats officiels du scrutin List of candidates by electoral district and individual results Liste des candidats par circonscription et résultats individuels Votes obtained Majority * Electoral district Candidate and affiliation Place of residence Occupation - - - - - - Votes obtenus Majorité * Circonscription Candidat et appartenance Lieu de résidence Profession No./Nbre % No./Nbre % Newfoundland/Terre-Neuve Bonavista--Trinity--Conception Brian Tobin (Lib.) St. John's, Nfld./T.-N. Politician/Politicien 22,096 54.4 11,087 27.3 Jim Morgan (P.C./P.-C.) Cupids, Nfld./T.-N. Businessman/Homme d'affaires 11,009 27.1 Fraser March (N.D.P./N.P.D.) Blaketown, Nfld./T.-N. Self-employed/Travailleur indépendant 6,473 15.9 Randy Wayne Dawe (Alliance) Clarke's Beach, Nfld./T.-N. Businessman/Homme d'affaires 1,051 2.6 Burin--St. George's Bill Matthews (Lib.) ** Mount Pearl, Nfld./T.-N. Parliamentarian/Parlementaire 14,603 47.5 6,712 21.8 Sam Synard (NIL) Marystown, Nfld./T.-N. Educator/Éducateur 7,891 25.7 Fred Pottle (P.C./P.-C.) Kippens, Nfld./T.-N. Businessman/Homme d'affaires 5,798 18.9 Peter Fenwick (Alliance) Cape St. George, Nfld./T.-N. Journalist/Journaliste 1,511 4.9 David Sullivan (N.D.P./N.P.D.) Torbay, Nfld./T.-N. Teacher/Enseignant 924 3.0 Gander--Grand Falls George Baker (Lib.) ** Gander, Nfld./T.-N. Parliamentarian/Parlementaire 15,874 55.0 7,683 26.6 Roger K. Pike (P.C./P.-C.) Grand Falls-Windsor, Nfld./T.-N.