Corn Cookbook

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

002 Mermaid Menu Nov2019.Indd

APPETIZERS MAIN SELECTIONS TORTILLA SOUP 6.75 / 9.25 SPAGHETTINI & SPICY RED SAUCE crimini mushrooms, spinach, zucchini, SOUP & SIDE SALAD 12 parmesan, garlic 16 19 | 23 LOW-FAT TURKEY CHILI with chicken with shrimp monterey jack cheese, cheddar jalapeño corn bread 8 with side salad 12 ROTISSERIE HERB CHICKEN CRISPY CALAMARI crisp half chicken, roasted garlic mashed potatoes, sweet chili soy aïoli 12 lemon-glazed vegetables, natural chicken sauce 17 FLAT BREAD SAUTÉED SALMON FILET brie cheese, mozzarella, green apples, oregano, drizzled with honey 12 grilled olive oil broccollini and asparagus, quinoa, artichokes, SWEDISH MEATBALLS and tomato, lemon vinaigrette 23 Helen Corbitt’s recipe; light brown gravy, nutmeg, grilled bread 12 JUMBO SHRIMP COCKTAIL classic cocktail sauce, lemon, horseradish 15 CHEESE SELECTION assorted domestic and imported cheese, sundried fruit, apple, assorted crackers 19 SANDWICHES ENTREE SALADS Sandwiches are served on Empire artisan breads. Side Salad substitute 2.5 CRAB LOUIE ROAST TURKEY, BACON, NM CHICKEN SALAD WITH BACON jumbo lump crab, greens, tomato, avocado, SWISS & AVOCADO OR TUNA PECAN egg, cucumber, louie dressing 24 toasted whole wheat, lettuce, tomato, served with chips 14 mayonnaise, chips 14 BISTRO SALAD RED RIVER YAHOO oven-roasted turkey, goat cheese, apples, sun-dried fruits, 16 FAJITA WRAP oven-roasted turkey, bacon, cheddar, grilled egg bread, spiced pecans, spinach, light balsamic ancho chicken, pico de gallo, pepper jack cheese, avocado, cranberry jalapeño jelly 14 lettuce, spicy ranch -

Ed Whitacre Fascinated the February 4, 2014 Crowd with His Experiences at Both AT&T and GM

HEADLINES VOL 7, NO. 49 Winter, 2014 Headliners – A Family Tradition for New Club President Wallace M. Smith t’s not like running for president of the United serve the Club,” Smith said. “Hopefully my service can give IStates, of course. There’s no two- or even four-year a little back to a place that has been and is very special to struggle to win the attention of enough voters to gain the me.” office. “Since we office in the building (practicing law with “I received a call from Tom Granger, who told me his partners in Smith, Robertson, Elliott & Douglas, L.L.P.) the committee charged with selecting officers wanted me to we eat lunch in the club a lot and sometimes go up to the serve the year after Judge Sparks,” bar in the late afternoon with says new Headliners president clients.” Wallace Smith. The Press Box is also the And now, that year has location of dinners that Wallace come and Wallace has taken on and Lanette, his wife of 29 years, the mantle of leadership of a share every couple of weeks or place he loves most because of so, watching a program on the the friendliness and genuineness TV or visiting with another of the people who staff the couple. Lanette is a frequent club operation. patron for her own purposes, “There is so little turnover hosting bridal showers or other that they know you and you get celebrations. to know them by name. I’ve been There’s also another family a member of other clubs and it tradition these days: Wallace’s wasn’t that way. -

Magazine Summer 2013

Austi n ColleMagazigne Summeer 2013 In a fast-changing, complex world, we’re preparing the next generation to think critically and respond thoughtfully. Austin College’s new IDEA Center—Inquiry, Discovery, Entrepreneurship, and Access—will equip students to innovate and excel in the competitive environment of life’s laboratory. From student-faculty research to community outreach, our new science complex will be at the center of the search for knowledge. Thi nk So the journey begins ... ooff tthhee tthhaatt aa rrouee t ther e The IDEA Center The IDEA Center: Opening Fall Term 2013 Homecoming Weekend Tours, October 25-26 L .................................................... .................................................... From the President .................................................... NEXT STEPS At Commencement in May, amid the excitement of graduates and their Our challenge in this cycle of planning will be to craft a living and families, I was pleased to note that “First Lady Emerita” Sara Bernice learning educational template that guides students from where they Moseley attended her 60th Austin College graduation ceremonies. What actually begin as freshmen toward the ideal of the Austin College graduate an achievement! That recognition turned bittersweet in mid-July as we as someone who is prepared to offer something of genuine value to the mourned Mrs. Moseley's passing. (See the article on page 6.) world. And we want the template to be robust enough to serve as a guide She was such a significant figure in the life of Austin College and in for future development and leadership throughout life. shaping the ideals and spirit of campus life today. Personally, I That work before us is made all the more complicated by the fact that Aappreciated her as a model of grace, leadership, and savvy. -

Stanley Marcus Did

Printed & bound A Newsletter for Bibliophiles February 2019 Printed & Bound focuses on the book as a collectible item and as an example of the printer’s art. It provides information about the history of printing and book production, guidelines for developing a book collection, and news about book-related publications and events. Articles in Printed & Bound may be reprinted free of charge SOMESUCH MINIATURE BOOKS provided that full attribution is given (name and date of Not many collectors of miniature books start their own publication, title and author of publishing companies to produce these tiny tomes, but that’s article, and copyright exactly what Stanley Marcus did. Already a noted collector information). Please request permission via email of rare and fine press books, as well as CEO of his family’s ([email protected]) before renowned Neiman-Marcus stores, Marcus then became a reprinting articles. Unless collector of miniature books. otherwise noted, all content is As his collection grew, Marcus’s first wife, Billie, written by Paula Jarvis, Editor decided that she would like to present him with a miniature and Publisher. version of his memoirs, Minding the Store, for his seventieth Printed & Bound birthday. However, while researching the world of Volume 6 Number 1 publishing, she realized that she should involve her husband February 2019 Issue in the process. Thus, Stanley Marcus embarked on his own publishing enterprise, dedicated to miniature books, and in © 2019 by Paula Jarvis c/o Nolan & Cunnings, Inc. 1975 brought out Minding the Store under his new Somesuch 28800 Mound Road Press imprint. (He had originally hoped to name it Nonesuch Warren, MI 48092 Press after the road he lived on, but that name was already in use by an English firm.) This first production was a bit Printed & Bound is published in disappointing as Marcus discovered that the greatly reduced February, June, and October. -

002 Mermaid Menu June2019.Indd

APPETIZERS MAIN SELECTIONS TORTILLA SOUP 6.75 / 9.25 cal 330 / 400 SPAGHETTINI & SPICY RED SAUCE crimini mushrooms, spinach, zucchini, SOUP & SIDE SALAD 11 parmesan, garlic 16 cal 650 19 | 23 LOW-FAT TURKEY CHILI with chicken with shrimp 7.5 11 cal 360 / 450 monterey jack cheese, cheddar jalapeño corn bread with side salad ROTISSERIE HERB CHICKEN CRISPY CALAMARI crisp half chicken, roasted garlic mashed potatoes, 15.5 cal 660 12 cal 820 lemon-glazed vegetables, natural chicken sauce sweet chili soy aïoli FLAT BREAD SAUTÉED SALMON FILET brie cheese, mozzarella, green apples, oregano, drizzled with honey 10 cal 970 grilled olive oil broccollini and asparagus, quinoa, artichokes, and tomato, lemon vinaigrette 21 SWEDISH MEATBALLS cal fat sat fat chol sodium carbs protein Helen Corbitt’s recipe; light brown gravy, nutmeg, grilled bread 10 cal 680 570 24 g 4.5 g 80 mg 850 mg 48 g 38 g JUMBO SHRIMP COCKTAIL classic cocktail sauce, lemon, horseradish 15 cal 290 CHEESE SELECTION assorted domestic and imported cheese, sundried fruit, apple, assorted crackers 18 SANDWICHES ENTREE SALADS Sandwiches are served on Empire artisan breads. Side Salad substitute 2.5 CRAB LOUIE ROAST TURKEY, BACON, NM CHICKEN SALAD WITH BACON jumbo lump crab, greens, tomato, avocado, SWISS & AVOCADO OR TUNA PECAN egg, cucumber, louie dressing 24 cal 420 toasted whole wheat, lettuce, tomato, served with chips 13.5 cal 880 / 730 BISTRO SALAD mayonnaise, chips 13.5 cal 740 RED RIVER YAHOO oven-roasted turkey, goat cheese, apples, sun-dried fruits, 15 FAJITA WRAP oven-roasted -

2016 the Howe Enterprise Howe Youth Baseball

http://howeenterprise.com/ Serving the community of Howe since 1963 Volume #54, Edition #9 Monday, July 18, 2016 howeenterprise.com Howe's That Public hearing tonight for The Eagle has landed The media can be an evil hotel in Howe force in this country. There is such pressure to feed the For those that like to give zone change from a C1 to economic machine for those conglomerate news sources their two cents on the future C2, on the property located such as CNN, Fox News, of Howe, tonight is their at the northeast intersection and of course the 'Big Four' (CBS, NBC, ABC and night. The City of Howe of N. Collins Freeway and FOX). They fight for Planning and Zoning W. Young Street. The Howe ratings because those who Commission (P&Z) will Enterprise learned that the have the most ratings, can get the most advertisers and hold a public hearing proposed use is for a hotel to charge the most money for tonight at 7 pm at 700 W. be built by Girishkumar advertising. Collectively, Haning St in Howe to Patel. The request for a the top 200 advertisers in consider the request for a continued on page 3 the United States spent a Cody Hartleben says, 'Welcome to Howe!' record $137.8 billion on advertising in 2014, up 2 percent year on year, Letter to editor: Local Howe Eagle Scout another town, no matter according to Ad Age's Hotel not good for Howe Cody Hartleben decided in how small they were, they annual "200 Leading seventh grade while had a giant saying telling National Advertisers" Submitted by Bill and Barbara Stambaugh report. -

Cookbooks Etc

Cookbooks Etc. Lee Adkins July 19, 2019 References [1] [2] Greece and It's Fabulous Foods Region by Region. Susaeta, Hellas S.A., Athens, GR. [3] Hugh Acheson. A New Turn in the South: Southern Flavors Reinven- ted for Your Kitchen. Clarkson Potter, New York, 2011. [4] Bruce Aidells and Denis Kelly. Hot Links and Country Flavors: Sausa- ges in American Regional Cooking. Knopf, 1990. [5] Vefa Alexiadou. Greece: The Cookbook. Phaidon, NY, 2016. [6] Jean Anderson and Elaine Hanna. The Doubleday Cookbook: Complete Contemporary Cooking. Doubleday & Company, Garden City, New York, 1975. [7] Pam Anderson. CookSmart: Perfect Recipes for Every Day. Houghton Mifflin, Boston, 2002. [8] Pepita Aris. Tapas & Traditional Spanish Cooking: The Authen- tic Taste Of Spain: 150 Sun-Drenched Classic And Regional Recipes Shown In 250 Stunning Photographs. Lorenz Books, 2008. [9] Cascia Parent Faculty Association. Gourmet Our Way. Cascia Parent Faculty Association, Tulsa, OK, 1995. 1 [10] Wesley Avila and Richard Parks III. Guerrilla Tacos: Recipes from the Streets of L.A. Ten Speed Press, California, 2017. Kindle. [11] Lee Bailey. Lee Bailey's New Orleans: Good Food and Glorious Hou- ses. Clarkson Potter, New York, 1993. [12] Lee Bailey. Lee Bailey's Cooking for Friends. Gramercy, 1998. [13] Lee Bailey. The Way I Cook. Gramercy, 2000. [14] Sabrina Baksh and Derrick Riches. Kebabs: 75 Recipes for Grilling. Harvard Common Press, Cambridge, 2017. [15] Douglas Baldwim. Sous Vide for the Home Cook Cookbook. Sous Vide, 2010. [16] Janet Ballantyne. Joy of Gardening Cookbook. Garden Way, Troy, New York, 1984. [17] David Barich and Thomas Ingalls. The Asian Grill. -

Cooking Their Culture: the Relationship Between

COOKING THEIR CULTURE: THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN COOKBOOKS AND THE WOMEN WHO OWNED THEM IN THE 1940s AND 1950s A Senior Honors Thesis by NORA C. COPE Submitted to the Office of Honors Programs Texas A&M University In partial fulfillment of the requirements of the UNIVERSITY UNDERGRADUATE RESEARCH FELLOWS April 2008 Major: American Studies ii ABSTRACT Cooking Their Culture: The Relationship Between Cookbooks and the Women Who Owned them in the 1940’s and 1950’s (April 2008) Nora Cope Department of American Studies Texas A&M University Fellows Advisor: Dr. Susan Stabile Department of American Studies My research explores the idea that the women of America’s past used cookbooks as life manuals and not just as collections of recipes. This project involves American gender roles and will be an important contribution to our women’s studies deficient academic community. I chose two different eras that have contrasting roles for women: World War II and the subsequent period of suburban growth. Next, I did a broad survey of as many cookbooks as I could that were published between 1942 and 1960, nationally distributed, and not regionally or ethnically focused. From this survey, I chose two books from each era that best represented these common characteristics to perform a close reading on each text not as literature, but as an artifact of material culture. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis benefited greatly from the support and funding received from the Office of Honors Programs and the Melbern G. Glasscock Center for Humanities Research. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ABSTRACT…………………………………………………………. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS…………………………..…….…….. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS…………………………………………. -

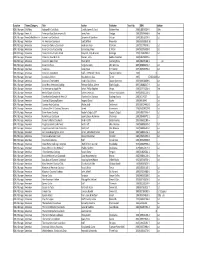

Cookbook Collection

Location Theme/Category Title Author Publisher Year Pub. ISBN edition CMU Storage SW/Mex. Kokopelli's Cook Book Cunkle, James & Carol Golden West 2008 188559024‐5 16th. CMU Storage Amer. # + American Food,Gastronomic St. Jones,Evan Vintage 1981 039474646‐5 2nd CMU Storage AmerCollectible. # + Fusion Food Cookbook Carpenter & Sandison Artisan 1994 188518300‐3 1st CMU Storage American All‐American Cookbook Scott,Willard Macmillan 1986 002608800‐26 CMU Storage American American Century Cookbook Anderson, Jean Clarkson ... 1997 051770576‐1 1st CMU Storage American American Country Cooking Emmerling, Mary C Potter 1987 051756020‐8 1st CMU Storage American American Country Inn B & B Maynard, Kitty & Lucian Rutledge 1990 155863059‐2 1st CMU Storage American American Food & Drink Mariani, John Lebhar‐Friedman 1999 086730784‐6 CMU Storage American American Mail‐Order Black‐Smith Running Press 1986 089471389‐2 pb CMU Storage American American Place Forgione, Larry Wm Morrow 1996 068808714‐7 1st CMU Storage American American... Jones, Evan E.P. Dutton 1975 052505353‐0 1st CMU Storage American America's Cook Book Staff ‐ NY Herald Tribune Charles Scribner 1940 0 CMU Storage American America's Kitchen Blue,Anthony Dias Turner 1995 1570361614 1st CMU Storage American America's Test Kitchen Cook's Illus. Editors Boston Common 2002 093618459‐0 1st CMU Storage American Art of New American Cooking Feltman‐Sailhac, Arlene Black Dog & L.. 1995 188482217‐7 1st CMU Storage American As American as Apple Pie Schulz, Phillip Stephen Wings 1996 051715034‐4 2nd -

Texas Radically Increased the Silt and Solids in the Kent Caperton and Craig Enoch Enjoyed Their Lunch Colorado River Water

HEADLINES BREAKFAST WITH SANTA Fall 2018 Grayson Howry helps his little sister Mattie get up on Santa’s lap. Henry Burnett mails a letter to Santa. Santa photo by Chris Caselli Santa and Birdie Levy have a good chat. Davis and Blake Baroch visit with Santa. The Rudy Garza Family EVENTS Breakfast with Santa November 24, 2018 Almost everyone in the Jones’ family was happy to be with Santa. photo by Chris Caselli by photo Jillian Becker made sure her letter to Santa made it to the mail box on time. Young Master Liam Walker was pleased his grandparents Lynn and Bill brought him to the party. Almost everyone in the Heath family was happy to be with Santa. Stephanie Jastrow and her daughter Claire (pretty in plaid) 2 EVENTS Breakfast with Santa November 24, 2018 Hector De Leon always enjoys an outing with his grandkids Anna, Henry and Winnie. Harry Osborne and his friend, Maddie Moncure, spent some good quality time writing to Santa. The Valdez family gets into the Christmas spirit at the club. The McDaniel family all dressed up for Santa. Will Jones brought his grandchildren to see Santa- Mae and Wally McNew. 3 INSIDE TRACK James Scott September 26, 2018 Have you ever wondered how self-driving cars work or how computers translate languages or approximate the human voice? These are just a few of the applications of artificial intel- ligence (AI) having nothing to do with “killer robots.” In a fascinating and completely understandable discussion of AI, Associate Professor James Scott of UT’s McCombs School of Business demonstrated why he is the recipient of the Regent’s Outstanding Teaching Award. -

Picton Cookbook – Recipe Pages – Check Your Downloaded Files

Aunt Ellen's Cheese Ball Ellen Chance Picton get-togethers wouldn't be complete without Aunt Ellen's cheese ball. 1 10 oz Cracker Barrel Sharp or Extra Sharp-Cheddar Cheese 2 packages (3 oz) Philadelphia Cream Cheese 2 jars Kraft Old English Cheese 3 pickled jalapeno chile peppers, finely chopped 3 cloves garlic, crushed 1 tablespoon Tabasco sauce paprika Seed and finely chop jalapenos. Let cream cheese and Old English cheese soften to room temperature. Grate Cracker Barrel cheese. Press or finely chop garlic. Mix all ingredients together. Form 2 balls or 4 balls. Sprinkle with Paprika. Chill. Will keep well in refrigerator, or freeze. Serve with crackers. Crab and Mushroom Hors D'oeuvres Grace Wise 2 jars (2 1/2 oz. each) sliced mushrooms 2 tablespoons scallions, sliced 1/2 stick margarine 1 tablespoon flour 1/2 cup heavy cream 1 tablespoon lemon juice 1 teaspoon finely chopped parsley 1 1/2 teaspoons prepared mustard 1/2 teaspoon salt 1/8 teaspoon cayenne 1/8 teaspoon paprika 12 ounces crabmeat (1 1/2 cup) 2 egg whites, stiffly beaten parsley, finely chopped 12 scallop shells Saute mushrooms and scallions briefly in margarine. Add flour and cook over very low heat, stirring constantly, for about 1 minute. Remove from heat. Add cream, lemon juice, 1 teaspoon parsley, mustard, salt, cayenne, and paprika. Cook over low heat until sauce is thickened, stirring constantly. Remove from heat and gently stir in crabmeat. Fold in egg whites. Fill scallop sheels with 1/4 cup of 19 mixture. Sprinkle with parsley. Place on baking sheet. -

Towersummer2011.Pdf

TOWER UNIVERSITY OF DALLAS MAGAZINE SUMMER 2011 An Enthusiastically Catholic Community of Learnerslegacy our PRESIDENT’S COLUMN Spotlight on Dan & Margie Cruse n 1955 Bishop Gorman called on members of the Catholic community to help him establish a Catholic university in Dallas Iwhich would support the work of the church. Mr. Edward Maher and Mr. Eugene Constantin, Jr. stepped forward. These men, with the help of the Sisters of St. Mary of Namur and Mr. John Carpenter, turned an idea into a physical reality. These giants and their families are commemorated throughout campus in the names of the Constantin College and the Maher Athletic Center. Mr. Constantin’s charge that UD be a distinguished university, not just another little Catholic college, has always been an inspirational vision for the University. The founders’ commitment to excellence was sustained by Mr. James Moroney, Jr., Mr. and Mrs. Patrick E. and Beatrice Haggerty, Mr. Ed Haggar, Mr. Tom Unis, Mr. Louis Maher, and the Constantin Foundation, among others, who made extraor- dinary contributions to the fledgling University. Nor would UD be the same without Mr. Joe Oscar Neuhoff or Mr. Gene Vilfordi, who have served on the Board of Trustees energetically for decades. Nor can we fail to mention Drs. Don and Louise Cowan who joined the faculty soon after the establishment of the University and became UD’s academic “godparents.” They were the inspiration and designers of the original Core Curriculum. These names were not only important to UD’s growth but sustained the Catholic Church in Dallas for the second half of the 21st century – they are the names of corporate giants, church leaders and brilliant intellectuals.