OPERATION PHOENIX: the Peaceful Atom Comes to Campus Joseph D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Is War Necessary for Economic Growth?

Historically Speaking-Issues (merged papers) 09/26/06 IS WAR NECESSARY FOR ECONOMIC GROWTH? VERNON W. RUTTAN UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA CLEMONS LECTURE SAINT JOHNS UNIVERSITY COLLEGEVILLE, MINNESOTA OCTOBER 9, 2006 1 OUTLINE PREFACE 3 INTRODUCTION 4 SIX GENERAL PURPOSE TECHNOLOGIES 5 The Aircraft Industry 6 Nuclear Power 7 The Computer Industry 9 The Semiconductor Industry 11 The Internet 13 The Space Industries 15 TECHNOLOGICAL MATURITY 17 IS WAR NECESSARY? 20 Changes in Military Doctrine 20 Private Sector Entrepreneurship 23 Public Commercial Technology Development 24 ANTICIPATING TECHNOLOGICAL FUTURES 25 PERSPECTIVES 28 SELECTED REFERENCES 32 2 PREFACE In a book published in 2001, Technology, Growth and Development: An Induced Innovation Perspective, I discussed several examples but did not give particular attention to the role of military and defense related research, development and procurement as a source of commercial technology development. A major generalization from that work was that government had played an important role in the development of almost every general purpose technology in which the United States was internationally competitive. Preparation for several speaking engagements following the publication of the book led to a reexamination of what I had written. It became clear to me that defense and defense related institutions had played a predominant role in the development of many of the general purpose technologies that I had discussed. The role of military and defense related research, development and procurement was sitting there in plain sight. But I was unable or unwilling to recognize it! It was with considerable reluctance that I decided to undertake the preparation of the book I discuss in this paper, Is War Necessary for Economic Growth? Military Procurement and Technology Development. -

Richard G. Hewlett and Jack M. Holl. Atoms

ATOMS PEACE WAR Eisenhower and the Atomic Energy Commission Richard G. Hewlett and lack M. Roll With a Foreword by Richard S. Kirkendall and an Essay on Sources by Roger M. Anders University of California Press Berkeley Los Angeles London Published 1989 by the University of California Press Berkeley and Los Angeles, California University of California Press, Ltd. London, England Prepared by the Atomic Energy Commission; work made for hire. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Hewlett, Richard G. Atoms for peace and war, 1953-1961. (California studies in the history of science) Bibliography: p. Includes index. 1. Nuclear energy—United States—History. 2. U.S. Atomic Energy Commission—History. 3. Eisenhower, Dwight D. (Dwight David), 1890-1969. 4. United States—Politics and government-1953-1961. I. Holl, Jack M. II. Title. III. Series. QC792. 7. H48 1989 333.79'24'0973 88-29578 ISBN 0-520-06018-0 (alk. paper) Printed in the United States of America 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 CONTENTS List of Illustrations vii List of Figures and Tables ix Foreword by Richard S. Kirkendall xi Preface xix Acknowledgements xxvii 1. A Secret Mission 1 2. The Eisenhower Imprint 17 3. The President and the Bomb 34 4. The Oppenheimer Case 73 5. The Political Arena 113 6. Nuclear Weapons: A New Reality 144 7. Nuclear Power for the Marketplace 183 8. Atoms for Peace: Building American Policy 209 9. Pursuit of the Peaceful Atom 238 10. The Seeds of Anxiety 271 11. Safeguards, EURATOM, and the International Agency 305 12. -

Case 1:12-Cv-07667-VEC-GWG Document 133 Filed 06/27/14 Page 1 of 120

Case 1:12-cv-07667-VEC-GWG Document 133 Filed 06/27/14 Page 1 of 120 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK ) BEVERLY ADKINS, CHARMAINE WILLIAMS, ) REBECCA PETTWAY, RUBBIE McCOY, ) WILLIAM YOUNG, on behalf of themselves and all ) others similarly situated, and MICHIGAN LEGAL ) SERVICES, ) ) Plaintiffs, ) Case No. 1:12-cv-7667-VEC ) v. ) EXPERT REPORT OF ) THOMAS J. SUGRUE MORGAN STANLEY, MORGAN STANLEY & ) IN SUPPORT OF CO. LLC, MORGAN STANLEY ABS CAPITAL I ) CLASS INC., MORGAN STANLEY MORTGAGE ) CERTIFICATION CAPITAL INC., and MORGAN STANLEY ) MORTGAGE CAPITAL HOLDINGS LLC, ) ) Defendants. ) ) 1 Case 1:12-cv-07667-VEC-GWG Document 133 Filed 06/27/14 Page 2 of 120 Table of Contents I. STATEMENT OF QUALIFICATIONS ................................................................................... 3 II. OVERVIEW OF FINDINGS ................................................................................................... 5 III. SCOPE OF THE REPORT .................................................................................................... 6 1. Chronological scope ............................................................................................................................ 6 2. Geographical scope ............................................................................................................................. 7 IV. RACE AND HOUSING MARKETS IN METROPOLITAN DETROIT ........................... 7 1. Historical overview ............................................................................................................................ -

The Oratory of Dwight D. Eisenhower

The oratory of Dwight D. Eisenhower Book or Report Section Accepted Version Oliva, M. (2017) The oratory of Dwight D. Eisenhower. In: Crines, A. S. and Hatzisavvidou, S. (eds.) Republican orators from Eisenhower to Trump. Rhetoric, Politics and Society. Palgrave MacMillan, pp. 11-39. ISBN 9783319685441 doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-68545-8 Available at http://centaur.reading.ac.uk/69178/ It is advisable to refer to the publisher’s version if you intend to cite from the work. See Guidance on citing . To link to this article DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-68545-8 Publisher: Palgrave MacMillan All outputs in CentAUR are protected by Intellectual Property Rights law, including copyright law. Copyright and IPR is retained by the creators or other copyright holders. Terms and conditions for use of this material are defined in the End User Agreement . www.reading.ac.uk/centaur CentAUR Central Archive at the University of Reading Reading’s research outputs online THE ORATORY OF DWIGHT D. EISENHOWER Dr Mara Oliva Department of History University of Reading [email protected] word count: 9255 (including referencing) 1 On November 4, 1952, Republican Dwight D. Eisenhower became the 34th President of the United States with a landslide, thus ending the Democratic Party twenty years occupancy of the White House. He also carried his Party to a narrow control of both the House of Representatives and the Senate. His success, not the Party’s, was repeated in 1956. Even more impressive than Eisenhower’s two landslide victories was his ability to protect and maintain his popularity among the American people throughout the eight years of his presidency. -

Timeline of the Cold War

Timeline of the Cold War 1945 Defeat of Germany and Japan February 4-11: Yalta Conference meeting of FDR, Churchill, Stalin - the 'Big Three' Soviet Union has control of Eastern Europe. The Cold War Begins May 8: VE Day - Victory in Europe. Germany surrenders to the Red Army in Berlin July: Potsdam Conference - Germany was officially partitioned into four zones of occupation. August 6: The United States drops atomic bomb on Hiroshima (20 kiloton bomb 'Little Boy' kills 80,000) August 8: Russia declares war on Japan August 9: The United States drops atomic bomb on Nagasaki (22 kiloton 'Fat Man' kills 70,000) August 14 : Japanese surrender End of World War II August 15: Emperor surrender broadcast - VJ Day 1946 February 9: Stalin hostile speech - communism & capitalism were incompatible March 5 : "Sinews of Peace" Iron Curtain Speech by Winston Churchill - "an "iron curtain" has descended on Europe" March 10: Truman demands Russia leave Iran July 1: Operation Crossroads with Test Able was the first public demonstration of America's atomic arsenal July 25: America's Test Baker - underwater explosion 1947 Containment March 12 : Truman Doctrine - Truman declares active role in Greek Civil War June : Marshall Plan is announced setting a precedent for helping countries combat poverty, disease and malnutrition September 2: Rio Pact - U.S. meet 19 Latin American countries and created a security zone around the hemisphere 1948 Containment February 25 : Communist takeover in Czechoslovakia March 2: Truman's Loyalty Program created to catch Cold War -

Eisenhower's Dilemma

UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN Eisenhower’s Dilemma How to Talk about Nuclear Weapons Paul Gregory Leahy 3/30/2009 Leahy 2 For Christopher & Michael, My Brothers Leahy 3 Table of Contents Introduction….6 Chapter 1: The General, 1945-1953….17 Chapter 2: The First Term, 1953-1957….43 Chapter 3: The Second Term, 1957-1961….103 Conclusion….137 Bibliography….144 Leahy 4 Acknowledgements I would to begin by taking a moment to thanks those individuals without whom this study would not be possible. Foremost among these individuals, I would like to thank Professor Jonathan Marwil, who had advised me throughout the writing of this thesis. Over countless hours he persistently pushed me to do better, work harder, and above all to write more consciously. His expert tutelage remains inestimable to me. I am gratified and humbled to have worked with him for these many months. I appreciate his patience and hope to have created something worth his efforts, as well as my own. I would like to thank the Department of History and the Honors Program for both enabling me to pursue my passion for history through their generous financial support, without which I could never have traveled to Abilene, Kansas. I would like to thank Kathy Evaldson for ensuring that the History Honors Thesis Program and the Department run smoothly. I also never could have joined the program were it not for Professor Kathleen Canning’s recommendation. She has my continued thanks. I would like to recognize and thank Professor Hussein Fancy for his contributions to my education. Similarly, I would like to recognize Professors Damon Salesa, Douglass Northrop, and Brian Porter-Szucs, who have all contributed to my education in meaningful and important ways. -

Environment and Natural Resources

A Guide To Historical Holdings in the Dwight D. Eisenhower Library NATURAL RESOURCES AND THE ENVIRONMENT Compiled By DAVID J. HAIGHT August 1994 NATURAL RESOURCES AND THE ENVIROMENT A Guide to Historical Materials in the Eisenhower Library Introduction Most scholars do not consider the years of the Eisenhower Administration to be a period of environmental action. To many historians and environmentalists, the push for reform truly began with the publication in 1962 of Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring, a critique of the use of pesticides, and the passage of the Wilderness Act in 1964. The roots of this environmental activity, however, reach back to the 1950s and before, and it is therefore important to examine the documentary resources of the Dwight D. Eisenhower Library. Following World War II, much of America experienced economic growth and prosperity. More Americans than ever before owned automobiles and labor saving household appliances. This increase in prosperity and mobility resulted in social changes which contain the beginnings of the modern environmental movement. With much more mobility and leisure time available more Americans began seeking recreation in the nation's forests, parks, rivers and wildlife refuges. The industrial expansion and increased travel, however, had its costs. The United States consumed great quantities of oil and became increasingly reliant on the Middle East and other parts of the world to supply the nation’s growing demand for fuel. Other sources of energy were sought and for some, atomic power appeared to be the answer to many of the nation’s energy needs. In the American West, much of which is arid, ambitious plans were made to bring prosperity to this part of the country through massive water storage and hydroelectric power projects. -

The Pre-History of Nuclear Development in Pakistan

Fevered with Dreams of the Future: The Coming of the Atomic Age to Pakistan* Zia Mian Too little attention has been paid to the part which an early exposure to American goods, skills, and American ways of doing things can play in forming the tastes and desires of newly emerging countries. President John F. Kennedy, 1963. On October 19, 1954, Pakistan’s prime minister met the president of the United States at the White House, in Washington. In Pakistan, this news was carried alongside the report that the Minister for Industries, Khan Abdul Qayyum Khan, had announced the establishment of an Atomic Energy Research Organization. These developments came a few months after Pakistan and the United States had signed an agreement on military cooperation and launched a new program to bring American economic advisers to Pakistan. Each of these initiatives expressed a particular relationship between Pakistan and the United States, a key moment in the coming into play of ways of thinking, the rise of institutions, and preparation of people, all of which have profoundly shaped contemporary Pakistan. This essay examines the period before and immediately after this critical year in which Pakistan’s leaders tied their national future to the United States. It focuses in particular on how elite aspirations and ideas of being modern, especially the role played by the prospect of an imminent ‘atomic age,’ shaped Pakistan’s search for U.S. military, economic and technical support to strengthen the new state. The essay begins by looking briefly at how the possibility of an ‘atomic age’ as an approaching, desirable global future took shape in the early decades of the twentieth century. -

"Blessing" of Atomic Energy in the Early Cold War Era

International Journal of Korean History (Vol.19 No.2, Aug. 2014) 107 The Atoms for Peace USIS Films: Spreading the Gospel of the "Blessing" of Atomic Energy in the Early Cold War Era Tsuchiya Yuka* Introduction In 1955 Blessing of Atomic Agency (原子力の恵み) was released. It was a 30-minute documentary made by the US Information Service in Tokyo to commemorate the 10th anniversary of the atomic bombings of Hiroshi- ma and Nagasaki. The film featured Japanese progress in “peaceful uses” of atomic energy, especially the use of radio-isotopes from the US Ar- gonne National Laboratory. They were widely used in Japanese scientific laboratories, national institutions and private companies in various fields including agriculture, medicine, industry, and disaster prevention. The film also introduced the nuclear power generation method, mentioning the commercial use of this technology in the US and Europe. It depicted Ja- pan as a nation that overcame the defeat of war and the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, enjoying the “blessing” of atomic energy, and striving to become a powerful country with science and technology. Not only was this film screened at American Centers, schools, or village halls all across Japan, but it was also translated into various different lan- * Professor, International/American Studies, Ehime University. 108 The Atoms for Peace USIS Films guages and screened in over 18 countries including the UK, Finland, In- donesia, Sudan, and Venezuela. Blessing of Atomic Agency was one of some 50 USIS films (govern- ment-sponsored information/education films) produced as part of the “Atoms for Peace” campaign launched by the US Eisenhower administra- tion (1953-1960). -

Four Decades of Stadium Planning in Detroit, 1936-1975

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 2016 Olympic Bids, Professional Sports, and Urban Politics: Four Decades of Stadium Planning in Detroit, 1936-1975 Jeffrey R. Wing Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Wing, Jeffrey R., "Olympic Bids, Professional Sports, and Urban Politics: Four Decades of Stadium Planning in Detroit, 1936-1975" (2016). Dissertations. 2155. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/2155 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 2016 Jeffrey R. Wing LOYOLA UNIVERSITY CHICAGO OLYMPIC BIDS, PROFESSIONAL SPORTS, AND URBAN POLITICS: FOUR DECADES OF STADIUM PLANNING IN DETROIT, 1936-1975 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY PROGRAM IN HISTORY BY JEFFREY R. WING CHICAGO, IL AUGUST 2016 Copyright by Jeffrey R. Wing, 2016 All rights reserved. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Writing this dissertation often seemed like a solitary exercise, but I couldn’t have accomplished it alone. I would like to thank Professor Elliott Gorn for his advice and support over the past few years. The final draft is much more focused than I envisioned when I began the process, and I have Prof. Gorn to thank for that. -

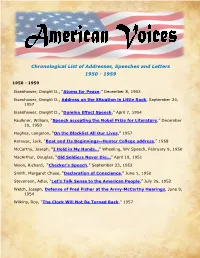

Chronological List of Addresses, Speeches and Letters 1950 - 1959

Chronological List of Addresses, Speeches and Letters 1950 - 1959 1950 - 1959 Eisenhower, Dwight D., “Atoms for Peace,” December 8, 1953 Eisenhower, Dwight D., Address on the Situation in Little Rock, September 24, 1957 Eisenhower, Dwight D., “Domino Effect Speech,” April 7, 1954 Faulkner, William, “Speech accepting the Nobel Prize for Literature,” December 10, 1950 Hughes, Langston, “On the Blacklist All Our Lives,” 1957 Kerouac, Jack, “Beat and Its Beginnings—Hunter College address,” 1958 McCarthy, Joseph, “I Hold in My Hands…” Wheeling, WV Speech, February 9, 1950 MacArthur, Douglas, “Old Soldiers Never Die…” April 19, 1951 Nixon, Richard, “Checker’s Speech,” September 23, 1952 Smith, Margaret Chase, “Declaration of Conscience,” June 1, 1950 Stevenson, Adlai, “Let’s Talk Sense to the American People,” July 26, 1952 Welch, Joseph, Defense of Fred Fisher at the Army-McCarthy Hearings, June 9, 1954 Wilkins, Roy, “The Clock Will Not Be Turned Back,” 1957 SOURCE: http://www.americanrhetoric.com/speeches/dwightdeisenhoweratomsforpeace.html Eisenhower, Dwight D., Atoms for Peace, December 8, 1953 *Madam President and* Members of the General Assembly: When Secretary General Hammarskjold’s invitation to address this General Assembly reached me in Bermuda, I was just beginning a series of conferences with the Prime Ministers and Foreign Ministers of Great Britain and of France. Our subject was some of the problems that beset our world. During the remainder of the Bermuda Conference, I had constantly in mind that ahead of me lay a great honor. That honor is mine today, as I stand here, privileged to address the General Assembly of the United Nations. -

Atoms for Peace Organized by The

Atoms for Peace Organized by the International Atomic Energy Agency In cooperation with the OECD/Nuclear Energy Agency (NEA) Nuclear Energy Institute (NEI) World Nuclear Association (WNA) The material in this book has been supplied by the authors and has not been edited. The views expressed remain the responsibility of the named authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the government of the designating Member State(s). The IAEA cannot be held responsible for any material reproduced in this book. International Symposium on Uranium Raw Material for the Nuclear Fuel Cycle: Exploration, Mining, Production, Supply and Demand, Economics and Environmental Issues (URAM-2009) ABSTRACTS Title Author (s) Page T0 - OPENING SESSION Address of Symposium President: The uranium world in F. J. Dahlkamp 1 9 transition from stagnancy to revival IAEA activities on uranium resources and production and C. Ganguly, J. Slezak 2 13 databases for the nuclear fuel cycle 3 A long-term view of uranium supply and demand R. Vance 15 T1 - URANIUM MARKETS & ECONOMICS ORAL PRESENTATIONS 4 Nuclear power has a bright outlook and information on G. Capus 19 uranium resources is our duty 5 Uranium Stewardship – the unifying foundation M. Roche 21 6 Safeguards obligations related to uranium/thorium mining A. Petoe 23 and processing 7 A review of uranium resources, production and exploration A. McKay, I. Lambert, L. Carson 25 in Australia 8 Paradigmatic shifts in exploration process: The role of J. Marlatt, K. Kyser 27 industry-academia collaborative research and development in discovering the next generation of uranium ore deposits 9 Uranium markets and economics: Uranium production cost D.