On Xerox University Microfilms

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Paul Gerhardt As a Hymn Writer and His Influence on English Hymnody

Paul Gerhardt as a Hymn Writer and his Influence on English Hymnody by Theodore Brown Hewitt About Paul Gerhardt as a Hymn Writer and his Influence on English Hymnody by Theodore Brown Hewitt Title: Paul Gerhardt as a Hymn Writer and his Influence on English Hymnody URL: http://www.ccel.org/ccel/hewitt/gerhardt.html Author(s): Hewitt, Theodore Brown Publisher: Grand Rapids, MI: Christian Classics Ethereal Library Description: A literary study of Gerhardt©s hymns and English translations of them. First Published: 1918 Publication History: First Edition: Yale University Press, 1918; Second Edition: Concordia Publishing House, 1976 Print Basis: Concordia Publishing House, 1976, omitting material still under copyright. Source: New Haven: Yale University Press Rights: Public Domain Date Created: 2002-09 Status: Profitable future work may include: ·(none under consideration) Editorial Comments: Orthography was edited to facilitate automated use: ·ThML markup (assuming HTML semantics of whitespace) ·Added hyperlinks to (original) translations by Winkworth and (possibly altered) translations by others, at CCEL. ·Added appendix including (possibly altered) translations from the Moravian Hymn Book, 1912; Hymnal and Order of Service, 1925; and Lutheran Hymnary, 1913, 1935. This allows access to all or parts of over 60 translated or adapted hymns. ·Added WWEC entries to authors and translators. Contributor(s): Stephen Hutcheson (Transcriber) Stephen Hutcheson (Formatter) LC Call no: BV330.G4H4 1918 LC Subjects: Practical theology Worship (Public and Private) Including the church year, Christian symbols, liturgy, prayer, hymnology Hymnology Table of Contents About This Book. p. ii Title Page. p. 1 Preface. p. 2 Contents. p. 3 Bibliography. p. 5 Chronological Table. -

The Musical Heritage of the Lutheran Church Volume I

The Musical Heritage of the Lutheran Church Volume I Edited by Theodore Hoelty-Nickel Valparaiso, Indiana The greatest contribution of the Lutheran Church to the culture of Western civilization lies in the field of music. Our Lutheran University is therefore particularly happy over the fact that, under the guidance of Professor Theodore Hoelty-Nickel, head of its Department of Music, it has been able to make a definite contribution to the advancement of musical taste in the Lutheran Church of America. The essays of this volume, originally presented at the Seminar in Church Music during the summer of 1944, are an encouraging evidence of the growing appreciation of our unique musical heritage. O. P. Kretzmann The Musical Heritage of the Lutheran Church Volume I Table of Contents Foreword Opening Address -Prof. Theo. Hoelty-Nickel, Valparaiso, Ind. Benefits Derived from a More Scholarly Approach to the Rich Musical and Liturgical Heritage of the Lutheran Church -Prof. Walter E. Buszin, Concordia College, Fort Wayne, Ind. The Chorale—Artistic Weapon of the Lutheran Church -Dr. Hans Rosenwald, Chicago, Ill. Problems Connected with Editing Lutheran Church Music -Prof. Walter E. Buszin The Radio and Our Musical Heritage -Mr. Gerhard Schroth, University of Chicago, Chicago, Ill. Is the Musical Training at Our Synodical Institutions Adequate for the Preserving of Our Musical Heritage? -Dr. Theo. G. Stelzer, Concordia Teachers College, Seward, Nebr. Problems of the Church Organist -Mr. Herbert D. Bruening, St. Luke’s Lutheran Church, Chicago, Ill. Members of the Seminar, 1944 From The Musical Heritage of the Lutheran Church, Volume I (Valparaiso, Ind.: Valparaiso University, 1945). -

Primärliteratur Für Die Mündliche Prüfung

1 Prof. A. Solbach Deutsches Institut Primärliteratur für die mündliche Prüfung Für die Lyrik-Themen nutzen Sie bitte folgenden Sammelband als Grundlage. Alle darin abgedruckten Gedichte des jeweiligen Autors sind Prüfungsgegenstand. Der neue Conrady. Das große deutsche Gedichtbuch von den Anfängen bis zur Gegenwart. Hg. v. Karl Otto Conrady. 2. Aufl. Düsseldorf u.a.: Artemis & Winkler, 2001. ISBN 3-538-06894-1 (Euro 24,90) Aus dem Gebiet 17. Jahrhundert: Angelus Silesius: Lyrik Johann Beer: Jucundus Jucundissimus Narrenspital Jakob Böhme: Prosa* Andreas Heinrich Bucholtz: Herkules und Valiska* Daniel Czepko: Lyrik Simon Dach: Lyrik Paul Fleming: Lyrik Paul Gerhardt: Lyrik Catherina Regina v. Greiffenberg: Lyrik Grimmelshausen: Simplicius Simplicissimus Courasche Andreas Gryphius: Leo Armenius Papinianus Horribilicribrifax Peter Squentz Johann Christian Günther: Lyrik Georg Philipp Harsdörffer: Frauenzimmer Gespräch-Spiele* Hofmann von Hofmannswaldau: Lyrik Quirinus Kuhlmann: Lyrik Friedrich v. Logau: Lyrik Daniel Caspar v. Lohenstein: Sophonisbe * Exzerpte 2 Cleopatra Großmütiger Feldherr Arminius* Æ Tod Neros Johann Michael Moscherosch: Philander von Sittewalt* Martin Opitz: Buch von der deutschen Poeterey Lyrik Übersetzung von John Barclays „Argenis“* Schäfferey von der Nimfen Hercinie Christian Reuter: Schlampampe (= L’Honette Femme oder die ehrliche Frau) Schelmuffsky Knorr v. Rosenroth: Lyrik Friedrich v. Spee: Lyrik Anton Ulrich: Aramena* Die Römische Octavia* Georg Rudolf Weckherlin: Lyrik Christian Weise: Masaniello Die drei -

Reclams Buch Der Deutschen Gedichte

1 Reclams Buch der deutschen Gedichte Vom Mittelalter bis ins 21. Jahrhundert Ausgewählt und herausgegeben von Heinrich Detering Reclam 2 3 Reclams Buch der deutschen Gedichte Band i 4 4., durchgesehene und erweiterte Auflage Alle Rechte vorbehalten © 2007, 2017 Philipp Reclam jun. GmbH & Co. KG, Stuttgart Gestaltung bis S. 851: Friedrich Forssman, Kassel Gestaltung des Schubers: Rosa Loy, Leipzig Satz: Reclam, Ditzingen Druck und buchbinderische Verarbeitung: GGP Media GmbH, Pößneck Printed in Germany 2017 reclam ist eine eingetragene Marke der Philipp Reclam jun. GmbH & Co. KG, Stuttgart isbn 978-3-15-011090-4 www.reclam.de Inhalt 5 Vorwort 9 [Merseburger Zaubersprüche] 19 • [Lorscher Bienensegen] 19 • Notker iii. von St. Gallen 20 • Der von Kürenberg 20 • Albrecht von Johansdorf 21 • Dietmar von Aist 23 • Friedrich von Hausen 24 • Heinrich von Morungen 25 • Heinrich von Veldeke 28 • [Du bist mîn, ich bin dîn] 29 • Hartmann von Aue 30 • Reinmar 30 • Walther von der Vogelweide 34 • Wolfram von Eschenbach 46 • Der Tannhäuser 48 • Neidhart 52 • Ulrich von Lichtenstein 55 • Mechthild von Magdeburg 57 • Konrad von Würzburg 59 • Frauenlob 61 • Johannes Hadloub 62 • Mönch von Salzburg 63 • Oswald von Wolkenstein 65 • Hans Rosenplüt 71 • Martin Luther 71 • Ulrich von Hutten 74 • Hans Sachs 77 • Philipp Nicolai 79 • Georg Rodolf Weckherlin 81 • Martin Opitz 83 • Simon Dach 85 • Johann Rist 91 • Friedrich Spee von Lan- genfeld 93 • Paul Gerhardt 96 • Paul Fleming 104 • Johann Klaj 110 • Andreas Gryphius 111 • Christian Hoffmann von Hoffmannswaldau -

Ein „Weiber-Freund"?

L'Homme Ζ. F. G. 13,2(2002) Ein „Weiber-Freund"? Entstehung und Rezeption von Wilhelm Ignatius Schütz „Ehren=Preiß des hochlöblichen Frauen=Zimmers" (1663), einem Beitrag zur Querelle des femmes Marion Kintzinger Mit seiner Schrift „Ehren=Preiß des hochlöblichen Frauen=Zimmers" trat der gelehrte Jurist Wilhelm Ignatius Schütz 1663 als vehementer Verteidiger des weiblichen Ge- schlechtes an die Öffentlichkeit. Entschieden setzte er sich für die These ein, dass der Verstand des weiblichen Geschlechtes dem des männlichen von Natur aus gleich, auch „zu Verrichtung tugendsamer Werck/ un(d) Thaten ebenmässig qualificirt, und geschickt sei".1 Seine Schrift wurde zu einem Erfolg.2 Hinter dem Pseudonym Poliandin verborgen, aber umso heftiger, attackierte ihn drei Jahre später der junge Literat Johann Gorgias. Entschieden verneinte er das aufgestellte Egalitätspostulat.3 Trotz zunächst breiter Rezeption, sogar durch Sigmund von Birken in einem Schäfer- gespräch über den „Ehrenpreis",4 gerieten Person und Werk später in Vergessenheit. Erst 1 Als Textausgabe künftig: Wilhelm Ignatius Schütz, Ehren=Preiß Deß Hochlöblichen Frauen=2mmers, Frank- furt 1663; Johann Gorgias, Gestiirtzter Ehren=Preiß des hochlöblichen Frauen=Zimmers, o.O., 1666, hg. von Marion Kintzinger u. Claudia Ulbrich, Hildesheim/Zürich/New York 2003, mit einer Bnleitung von Marion Kintzinger - Schütz im Text zitiert als „Ehrenpreis", Gorgias als „Gestürtzter Ehrenpreis". 2 Im Jahr 1673 erschien eine zweite, in der Niedersächsischen Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek Göttin- gen als Verlust geltende Auflage, die nach Hajek entschärft worden sein soll. Sie enthält einen Brief- wechsel zwischen zwei adeligen Frauen, datiert auf den 16. Dezember 1665. Egon Hajek, Johann Gor- gias. Ein verschollener Dichter des 17. Jahrhunderts, in: Euphorion, 24 (1925), 22-49, 197-240, 205, Anm. -

![[' 2. 0 0 7-] Poetics and Rhetorics in Early Modern Germany](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6851/2-0-0-7-poetics-and-rhetorics-in-early-modern-germany-1126851.webp)

[' 2. 0 0 7-] Poetics and Rhetorics in Early Modern Germany

Early Modern German Literature 1350-1700 Edited by Max Reinhart Rochester, New York u.a. CAMDEN HOUSE [' 2. 0 0 7-] Poetics and Rhetorics in Early Modern Germany Joachim Knape ROM ANTIQUIIT ON, REFLECTION ON MEANS of communication - an texts Fin general and poetic texts in particular- brought about two distinct gen res of theoretical texts: rhetorics and poetics. Theoretical knowledge was sys tematized in these two genres for instructional purposes, and its practical applications were debated down to the eighteenth century. At the center of this discussion stood the communicator (or, text producer), armed with pro cedural options and obligations and with the text as his primary instrument of communication. Thus, poeto-rhetorical theory always derived its rules from and reflected the prevailing practice.1 This development began in the fourth century B.C. with Aristotle's Rhetoric and Poetics, which he based an the public communicative practices of the Greek polis in politics, theater, and poetic performance. In the Roman tra dition, rhetorics2 reflectcd the practice of law in thc forum (genus iudiciale), political counsel (genus deliberativum), and communal decisions regarding issues of praise and blame (genus demonstrativum). These comprise the three main speech situations, or cases (genera causarum). The most important the oreticians of rhetoric were Cicero and Quintilian, along with the now unknown author (presumed in the Middle Ages to have been Cicero) of the rhetorics addressed to Herennium. As for poetics, aside from the monumental Ars poet ica ofHorace, Roman literature did not have a particularly rich theoretical tra dition. The Hellenistic poetics On the Sublime by Pseudo-Longinus (first century A.D.) was rediscovered only in the seventeenth century in France and England; it became a key work for modern aesthetics. -

Bach Chor Berlin

BACH-CHOR AN DER KAISER-WILHELM-GEDÄCHTNIS-KIRCHE JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH Sehet, wir gehn hinauf gen Jerusalem BWV 159 Sonnabend, 2. März 2019, 18 Uhr Kaiser-Wilhelm-Gedächtnis-Kirche Berlin Mitwirkende Kantategottesdienst Alt Susanne Langner Tenor Volker Arndt JOHANN PACHELBEL Ciacona f-Moll 1653-1706 Bass Philipp Kaven Orgelpositiv Peter Uehling Orgel Jonas Sandmeier Bach-Chor Liturgin Eingangsvotum Bach-Collegium Leitung Achim Zimmermann Gebet Liturgin Pfarrerin Kathrin Oxen Schriftlesung: 1. Korinther 13,1-13 Am Ausgang erbitten wir sehr herzlich eine Spende zur Durchführung unserer Kantategottesdienste. 2 1 Gemeinde Wir glauben all an einen Gott [EG 183] Liturgin Schriftlesung: Lukas 18,31-43 Ansprache Gemeinde Lasset uns mit Jesus ziehen [EG 384] . : . 2. Lasset uns mit Jesus leiden, / seinem Vorbild werden gleich; / nach dem Leide folgen Freuden, / Armut hier macht dorten reich, / Tränensaat, die erntet Lachen; / Hoffnung tröste die Geduld: / Es kann leichtlich Gottes Huld / aus dem Regen Sonne machen. / Jesu, hier leid ich mit dir, / dort teil deine Freud mit mir! 4. Lasset uns mit Jesus leben. / Weil er auferstanden ist, / muss das Grab uns wiedergeben. / Jesu, unser Haupt du bist, / wir sind deines Leibes Glieder, / wo du lebst, da leben wir; / ach erkenn uns für und für, / trauter Freund, als deine Brüder! / Jesu, dir ich lebe hier, / dorten ewig auch bei dir. Text: Sigmund von Birken 1653 Melodie: Sollt ich meinem Gott nicht singen (Nr. 325) Liturgin Biblisches Votum 2 3 J. S. BACH Sehet, wir gehn hinauf gen Jerusalem Recitativo -

Yale Collection of German Baroque Literature Author Index 1

Yale Collection of German Baroque Literature Author Index Abel, Caspar. Abele, Matthias, d.1677. Diarium Belli Hispanici, oder Vollstindiges Tag-Register Vivat oder so genandte künstliche Unordnung. des jetzigen Spanischen Krieges wie er Von 1701. Nürnberg, Bey Michael und Johann Friederich Endtern. 1670 zur Recommendation Eines Auff den blank Januarii. 1707 Item No. 659a; [I.-V. und letzter Theil] Worinnen 40.[i.e. 160] Item No. 1698b; bis 1707. ... geführet worden samt... dem was wunderseltzame Geschichte...meist aus eigener Erfahrung, sich mit den Ungern und Sevennesern zugetragen...; zusammen geschrieben...durch Matthiam Abele, von und zu angestellten Actus Oratorii, ... heraus gegeben Von Casp. Lilienberg...; [75]; 4v. in 2. fronts. (v.1,2) 13-14 cm.; Title and Abeln ... Halberstadt Gedruckt bey Joh. Erasmus Hynitzsch imprint of 3,5 vary; Vol.1 has title: Künstliche Unordnung; Königl. Preuß. Hof-Buchdr; [12]p., 34 cm. Signatures: [A] - das ist, Wunder-seltsame, niemals in offentlichen Druck C2. gekommene...Begebenheiten...Zum andernmal aufgelegt. Reel: 603 [n.p.]. Reel: 160 Abel, Caspar, 1676-1763. Caspar Abels auserlesene Satirische Gedichte, worinnen Abraham à Sancta Clara, 1644?-1709. viele jetzo im Schwange gehende Laster, auf eine zwar freye, Abrahamische Lauber-Hütt. und schertzhaffte doch vernünfftige Art gestrafet werden; und Wien und Mürnberg, Verlegts J.P. Krauss. 1723-38 Theils ihrer Vortrefligkeit halber aus dem berühmten Boileau Item No. 1131; Ein Tisch mit Speisen in der Mitt...Denen und Horatio übersetzet Theils auch nach deren Vorbilde Juden zum Trutz, denen Christen zum Nutz an- und verfertiget sind. aufgerichtet, wie auch mit mit vielen auserlesenen so wohl Quedlinburg und Aschersleben, verlegts Gottlob Ernst biblischen als andern sinnreichen Concepten, Geschichten und Struntze. -

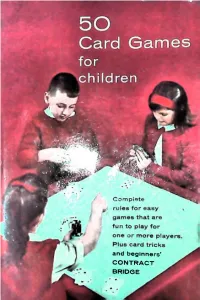

And Beginners' CONTRACT BRIDGE ■ I T !

and beginners' CONTRACT BRIDGE ■ I t ! : CHILDREN By VERNON QUINN * With an Easy Lesson in Contract Bridge COMPLETE LAYOUTS FOR PLAYING the united states playing CARD CO. f CINCINNATI, OHIO, U. S. A. ■ 3 CONTENTS > ( Something About Cards 5 Copyright, MCMXXXHI, by Vernon Quinn CARD GAMES THAT ARE FUN TO PLAY 1. Menagerie ................... 9 All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced without the 2. Donkey.......................... 11 written permission of the publishers. 3. Spade the Gardener .. 12 4. Snip-Snap-Snorem........ H 5. The Earl of Coventry 15 6. I Doubt It.................... 16 Copyright, MCMXLVI, by 7. War................................ 17 WHITMAN PUBLISHING COMPANY 8. Concentration ............ 19 Racine, Wisconsin 9. Rolling Stone.............. 21 printed in u.s.a. 10. Linger Long ................ 22 11. Stay Away.................... 23 12. Hearts .......................... 24 13. Frogs in the Pond___ 25 14. Twenty-Nine .............. 27 15. Giggle a Bit................ 29 16. My Ship Sails.............. 30 17. Stop-and-Go ................ 32 18. Yukon .......................... 33 19. Old Maid...................... 36 20. Go Fishing.................. 37 TWELVE GAMES OF SOLITAIRE 21. Pirate Gold ................................ 39 To 22. Pyramid........................................ 41 23. Montana .................................... 43 Joan and Ann 24. Lazy Boy.................................... 45 and 25. Round the Clock...................... 46 26. Spread Eacle.............................. 47 'Richard -

University of Birmingham Rethinking Agency and Creativity

University of Birmingham Rethinking agency and creativity Brown, Hilary DOI: 10.1080/14781700.2017.1300103 License: None: All rights reserved Document Version Peer reviewed version Citation for published version (Harvard): Brown, H 2017, 'Rethinking agency and creativity: translation, collaboration and gender in early modern Germany', Translation Studies, vol. 11, no. 1, pp. 84-102. https://doi.org/10.1080/14781700.2017.1300103 Link to publication on Research at Birmingham portal Publisher Rights Statement: This is an Accepted Manuscript of an article published by Taylor & Francis in Translation Studies on 18th April 2017, available online: http://www.tandfonline.com/10.1080/14781700.2017.1300103. General rights Unless a licence is specified above, all rights (including copyright and moral rights) in this document are retained by the authors and/or the copyright holders. The express permission of the copyright holder must be obtained for any use of this material other than for purposes permitted by law. •Users may freely distribute the URL that is used to identify this publication. •Users may download and/or print one copy of the publication from the University of Birmingham research portal for the purpose of private study or non-commercial research. •User may use extracts from the document in line with the concept of ‘fair dealing’ under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 (?) •Users may not further distribute the material nor use it for the purposes of commercial gain. Where a licence is displayed above, please note the terms and conditions of the licence govern your use of this document. When citing, please reference the published version. -

Gather Everyone Together

Gather Everyone Together A Family Engagement E-Letter from the ADAMHS Board Prevention Project SPECIAL EDITION: GET SHUFFLIN’ Get Shufflin’ Together! Research suggests shows that card-related games could benefit our mental and emotional wellbeing. Playing cards is a way to keep our minds healthy, connect to others, and simply relax. Card games can expand our brain power, delay cognitive disorders, and exercise many social skills such as respect, hones- ty, and patience to name a few. Card games can even improve self-confidence in social environments and allow some to relax and cope with stress! Less competitive or one player games can give your brain time to relax and unwind after a long day. In the end, card games are another form of entertainment and meant to be fun. These days, it is hard to avoid being “plugged into” some sort of electronic device for work or school so what better way to break away from your screens and connect with your most im- portant followers – your loved ones at home! We even created a special deck of cards that serves dual purpose during this unique time in history: you can play your favorite games while pondering thoughts on life and living. If you didn’t get a deck, email: [email protected] so your family can GET Shufflin’! Game On! Schedule a weekly game night to play your family favorites or start a new tradition. Or challenge yourselves to learn a new game each day. Everyone ben- efits from face to face time together. Here are a few popular games to get you started: Blitz (2-12 players) -Also known as "Scat," "Thirty-One," and "Ride the Bus.” Players draw and discard a card each turn with the aim of trying to improve their three card hand. -

The Library of Alexandria the Library of Alexandria

THE LIBRARY OF ALEXANDRIA THE LIBRARY OF ALEXANDRIA THE LIBRARY OF ALEXANDRIA CENTRE OF LEARNING IN THE ANCIENT WORLD Edited by Roy MACLEOD I.B.TAURIS www.ibtauris.com Reprinted in 2010 by I.B.Tauris & Co Ltd 6 Salem Road, London W2 4BU 175 Fifth Avenue, New York NY 10010 www.ibtauris.com Distributed in the United States and Canada Exclusively by Palgrave Macmillan 175 Fifth Avenue, New York NY 10010 Revised paperback edition published in 2004 by I.B.Tauris & Co Ltd Paperback edition published in 2002 by I.B.Tauris & Co Ltd First published in 2000 by I.B.Tauris & Co Ltd Copyright © Roy MacLeod, 2000, 2002, 2004 The right of Roy MacLeod to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by the author in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or any part thereof, may not be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. ISBN: 978 1 85043 594 5 A full CIP record for this book is available from the British Library A full CIP record is available from the Library of Congress Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: available Typeset by The Midlands Book Typesetting Co., Loughborough, Leicestershire Printed and bound in India by Thomson Press India Ltd Contents Notes on Contributors VB Map of Alexandria x Preface Xl Introduction: Alexandria in History and Myth Roy MacLeod Part I.