Minder-Baker-Hoey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Film, Television and Video Productions Featuring Brass Bands

Film, Television and Video productions featuring brass bands Gavin Holman, October 2019 Over the years the brass bands in the UK, and elsewhere, have appeared numerous times on screen, whether in feature films or on television programmes. In most cases they are small appearances fulfilling the role of a “local” band in the background or supporting a musical event in the plot of the drama. At other times band have a more central role in the production, featuring in a documentary or being a major part of the activity (e.g. Brassed Off, or the few situation comedies with bands as their main topic). Bands have been used to provide music in various long-running television programmes, an example is the 40 or more appearances of Chalk Farm Salvation Army Band on the Christmas Blue Peter shows on BBC1. Bands have taken part in game shows, provided the backdrop for and focus of various commercial advertisements, played bands of the past in historical dramas, and more. This listing of 450 entries is a second attempt to document these appearances on the large and small screen – an original list had been part of the original Brass Band Bibliography in the IBEW, but was dropped in the early 2000s. Some overseas bands are included. Where the details of the broadcast can be determined (or remembered) these have been listed, but in some cases all that is known is that a particular band appeared on a certain show at some point in time - a little vague to say the least, but I hope that we can add detail in future as more information comes to light. -

An Examination of the Causes of Education Policy Outputs in Ontario, Saskatchewan, and Alberta

Why Do Parties Not Make a Difference? An Examination of the Causes of Education Policy Outputs in Ontario, Saskatchewan, and Alberta By Saman Chamanfar A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements of the degree of Ph.D. Political Science University of Toronto © Copyright by Saman Chamanfar 2017 Why Do Parties Not Make a Difference? An Examination of the Causes of Education Policy Outputs in Ontario, Saskatchewan, and Alberta Saman Chamanfar Doctor of Philosophy Political Science University of Toronto 2017 Abstract This study seeks to explain why partisanship—contrary to what we might expect based on the findings of other studies concerning social policies—is generally not a useful explanatory variable when examining the primary and secondary education policies of three Canadian provinces (Ontario, Saskatchewan, and Alberta) during two periods (the 1970s and 1990- 2008). Four specific areas of the education sector of the provinces will be examined: objectives of curricula; spending; ministry relations with school boards; and government policies concerning private and charter schools. Utilizing a qualitative approach and building on the findings of other studies on provincial education systems, it will be argued that in order to understand why the three provinces generally adopted similar policies in both periods, regardless of the differences in the ideologies of governing parties, we need to consider the causal effect of key ideas in both periods. In addition, it will be shown that opposition parties in most instances did not present policies that differed from those of governing parties or criticize the policies of such parties. This will further illustrate the limited usefulness of adopting a partisanship lens when seeking to understand the policy positions of various parties in the provinces concerning the education sector. -

Lublin Studies in Modern Languages and Literature

Lublin Studies in Modern Languages and Literature VOL. 43 No 2 (2019) ii e-ISSN: 2450-4580 Publisher: Maria Curie-Skłodowska University Lublin, Poland Maria Curie-Skłodowska University Press MCSU Library building, 3rd floor ul. Idziego Radziszewskiego 11, 20-031 Lublin, Poland phone: (081) 537 53 04 e-mail: [email protected] www.wydawnictwo.umcs.lublin.pl Editorial Board Editor-in-Chief Jolanta Knieja, Maria Curie-Skłodowska University, Lublin, Poland Deputy Editors-in-Chief Jarosław Krajka, Maria Curie-Skłodowska University, Lublin, Poland Anna Maziarczyk, Maria Curie-Skłodowska University, Lublin, Poland Statistical Editor Tomasz Krajka, Lublin University of Technology, Poland International Advisory Board Anikó Ádám, Pázmány Péter Catholic University, Hungary Monika Adamczyk-Garbowska, Maria Curie-Sklodowska University, Poland Ruba Fahmi Bataineh, Yarmouk University, Jordan Alejandro Curado, University of Extramadura, Spain Saadiyah Darus, National University of Malaysia, Malaysia Janusz Golec, Maria Curie-Sklodowska University, Poland Margot Heinemann, Leipzig University, Germany Christophe Ippolito, Georgia Institute of Technology, United States of America Vita Kalnberzina, University of Riga, Latvia Henryk Kardela, Maria Curie-Sklodowska University, Poland Ferit Kilickaya, Mehmet Akif Ersoy University, Turkey Laure Lévêque, University of Toulon, France Heinz-Helmut Lüger, University of Koblenz-Landau, Germany Peter Schnyder, University of Upper Alsace, France Alain Vuillemin, Artois University, France v Indexing Peer Review Process 1. Each article is reviewed by two independent reviewers not affiliated to the place of work of the author of the article or the publisher. 2. For publications in foreign languages, at least one reviewer’s affiliation should be in a different country than the country of the author of the article. -

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} up the Junction by Nell Dunn up the JUNCTION (1967) from the Collection of Short Stories 'Up the Junction' by Nell Dunn Published in 1963

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Up the Junction by Nell Dunn UP THE JUNCTION (1967) From the collection of short stories 'Up the Junction' by Nell Dunn published in 1963. Nell Dunn was an upper-class woman who went 'slumming' in Battersea in 1959 and wrote a series of sketches (sketches being a much more appropriate term than short stories) which were published in 1963 (my copy has the cover on the left above) as 'Up the Junction'. Four of the pieces were published in The New Statesman. The stories mainly revolve around three working-class women, sisters Sylvie and Rube and an unnamed narrator. The first story, 'Out with the Girls', begins: We stand, the three of us, me, Sylvie and Rube, pressed up against the saloon door, brown ales clutched in our hands. Rube, neck stiff so as not to shake her beehive, stares sultrily round the packed pub. Sylvie eyes the boy hunched over the mike and shifts her gaze down to her breasts snug in her new pink jumper. 'Kiss! Kiss! Kiss!' he screams. Three blokes beckon us over to their table. Rube doubles up with laughter. 'Come on, then. They can buy us some beer.' 'Hey, look out, yer steppin' on me winkle!' Dignified, the three of us squeeze between tables and sit ourselves, knees tight together, daintily on the chairs. 'Three browns, please,' says Sylvie before we've been asked. The first version of 'Up the Junction' was of course Ken Loach and Tony Garnett's filming of the book for the Play for Today strand in 1965, with Carol White as Sylvie, Geraldine Sherman as Rube and Vickery Turner as Eileen, presumably the unnamed narrator of the book. -

Human' Jaspects of Aaonsí F*Oshv ÍK\ Tke Pilrns Ana /Movéis ÍK\ É^ of the 1980S and 1990S

DOCTORAL Sara MarHn .Alegre -Human than "Human' jAspects of AAonsí F*osHv ÍK\ tke Pilrns ana /Movéis ÍK\ é^ of the 1980s and 1990s Dirigida per: Dr. Departement de Pilologia jA^glesa i de oermanisfica/ T-acwIfat de Uetres/ AUTÓNOMA D^ BARCELONA/ Bellaterra, 1990. - Aldiss, Brian. BilBon Year Spree. London: Corgi, 1973. - Aldridge, Alexandra. 77» Scientific World View in Dystopia. Ann Arbor, Michigan: UMI Research Press, 1978 (1984). - Alexander, Garth. "Hollywood Dream Turns to Nightmare for Sony", in 77» Sunday Times, 20 November 1994, section 2 Business: 7. - Amis, Martin. 77» Moronic Inferno (1986). HarmorKlsworth: Penguin, 1987. - Andrews, Nigel. "Nightmares and Nasties" in Martin Barker (ed.), 77» Video Nasties: Freedom and Censorship in the MecBa. London and Sydney: Ruto Press, 1984:39 - 47. - Ashley, Bob. 77» Study of Popidar Fiction: A Source Book. London: Pinter Publishers, 1989. - Attebery, Brian. Strategies of Fantasy. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1992. - Bahar, Saba. "Monstrosity, Historicity and Frankenstein" in 77» European English Messenger, vol. IV, no. 2, Autumn 1995:12 -15. - Baldick, Chris. In Frankenstein's Shadow: Myth, Monstrosity, and Nineteenth-Century Writing. Oxford: Oxford Clarendon Press, 1987. - Baring, Anne and Cashford, Jutes. 77» Myth of the Goddess: Evolution of an Image (1991). Harmondsworth: Penguin - Arkana, 1993. - Barker, Martin. 'Introduction" to Martin Barker (ed.), 77» Video Nasties: Freedom and Censorship in the Media. London and Sydney: Ruto Press, 1984(a): 1-6. "Nasties': Problems of Identification" in Martin Barker (ed.), 77» Video Nasties: Freedom and Censorship in the MecBa. London and Sydney. Ruto Press, 1984(b): 104 - 118. »Nasty Politics or Video Nasties?' in Martin Barker (ed.), 77» Video Nasties: Freedom and Censorship in the Medß. -

British Film and TV Since 1960 COM FT 316 (Core Course)

British Film and TV Since 1960 COM FT 316 (Core Course) Instructor Information Names Ms Kate Domaille; Dr Christine Fanthome Course Day and Meeting Time [Weekdays], [time] Course Location [Name] Room, 43 Harrington Gardens, SW7 4JU BU Telephone 020 7244 6255 Email Addresses [email protected]; [email protected] Office Hours By appointment Course Description In this course you will learn how British film and television has evolved from the 1960s to the present day You will undertake a series of case studies of British film and television genres and examine how the aesthetics, audience expectations and production conventions have changed over time You will develop a deep set of analytic skills for appreciating the evolution of British film and television The course provides opportunities to appreciate the specific evolution of film and television in the British context from the 1960s to the present day through the study of production conventions, representation and audiences. A close focus is placed on the development of film and television through an examination of industry movement and changing audience expectations over time. The course offers opportunities to analyse and evaluate social change through the medium of film and television. Subjects covered in individual sessions include comedy, crime, fantasy, art film and TV, youth culture, heritage drama, the ethics and logistics of filming in public spaces, documentary and social realism, and new documentary which will encompass reality TV and citizen journalism. Course Objectives On completion of the course, the successful student will show evidence of being able to: interpret film or television texts in terms of their understanding of the cultural contexts in which those works were created. -

Papers of John L. (Jack) Sweeney and Máire Macneill Sweeney LA52

Papers of John L. (Jack) Sweeney and Máire MacNeill Sweeney LA52 Descriptive Catalogue UCD Archives School of History and Archives archives @ucd.ie www.ucd.ie/archives T + 353 1 716 7555 F + 353 1 716 1146 © 2007 University College Dublin. All rights reserved ii CONTENTS CONTEXT Biographical history iv Archival history v CONTENT AND STRUCTURE Scope and content v System of arrangement vi CONDITIONS OF ACCESS AND USE Access xiv Language xiv Finding-aid xiv DESCRIPTION CONTROL Archivist’s note xiv ALLIED MATERIALS Allied Collections in UCD Archives xiv Related collections elsewhere xiv iii Biographical History John Lincoln ‘Jack’ Sweeney was a scholar, critic, art collector, and poet. Born in Brooklyn, New York, he attended university at Georgetown and Cambridge, where he studied with I.A. Richards, and Columbia, where he studied law. In 1942 he was appointed curator of Harvard Library’s Poetry Room (established in 1931 and specialising in twentieth century poetry in English); curator of the Farnsworth Room in 1945; and Subject Specialist in English Literature in 1947. Stratis Haviaras writes in The Harvard Librarian that ‘Though five other curators preceded him, Jack Sweeney is considered the Father of the Poetry Room …’. 1 He oversaw the Poetry Room’s move to the Lamont Library, ‘establishing its philosophy and its role within the library system and the University; and he endowed it with an international reputation’.2 He also lectured in General Education and English at Harvard. He was the brother of art critic and museum director, James Johnson Sweeney (Museum of Modern Art, New York; Solomon R. -

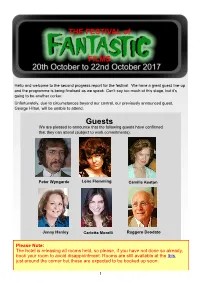

Guests We Are Pleased to Announce That the Following Guests Have Confirmed That They Can Attend (Subject to Work Commitments)

Hello and welcome to the second progress report for the festival. We have a great guest line-up and the programme is being finalised as we speak. Can’t say too much at this stage, but it’s going to be another corker. Unfortunately, due to circumstances beyond our control, our previously announced guest, George Hilton, will be unable to attend. Guests We are pleased to announce that the following guests have confirmed that they can attend (subject to work commitments). Peter Wyngarde Lone Flemming Camille Keaton Jenny Hanley Carlotta Morelli Ruggero Deodato Please Note: The hotel is releasing all rooms held, so please, if you have not done so already, book your room to avoid disappointment. Rooms are still available at the Ibis, just around the corner but these are expected to be booked up soon. 1 Welcome to the Festival : Once again the Festival approaches and as always it is great looking forward to meeting old friends again and talking films. The main topic of conversation so far this year seems to be the imminent arrival of some more classic Hammer films on Blu Ray, at long last. Like so many of you, I am very much looking forward to these and it is fortuitous that this year Jenny Hanley is making a return visit to our festival, just as her Hammer magnum opus with Christopher Lee and Dennis Waterman, Scars of Dracula is on the list of new blu rays being released. I am having to face the inevitable question of how much longer I can go on, but that is not your problem. -

Labor Relations, 16Mm Film and Euston Films

Scope: An Online Journal of Film and Television Studies Issue 26 February 2014 Labor Relations, 16mm Film and Euston Films Max Sexton, Birkbeck College, University of London Film as a technology has been used, adapted and implemented in particular ways within television. This article provides examples of this process along with its complexities and demonstrates how a system of regulated labor on British television during the 1970s shaped the aesthetic form that 16mm film was used to develop. The questions of how far the production process was guided by institutionalized conventions, however, is one that the article seeks to answer in its analysis of the function and form of the filmed television series produced by Euston Films, a subsidiary of Thames Television. Charles Barr (1996) has discussed the legacy of live television that seeks to develop analyses of the developing formal systems of early television. For example, the telerecordings of most of the Quatermass serials were only “television films” because they were recorded on film, but were not constructed or edited as film, although they may have used some film inserts. According to Barr, television drama may have been shot on film, but it was different from film. It was only later in the 1960s and 1970s that shooting on film meant that the studio drama was replaced by shooting on location on 16mm. Barr notes that in Britain, unlike in the US, if a growing proportion of drama was shot on film, dramas were still referred to as “plays.” Consequently, the TV plays-on-film were distinct from “films.” However, as this article demonstrates, the development of the 16mm film from the 1970s complicates some of the notions that television drama was either live or continued to be planned, shot and edited as a live play. -

Celluloid Television Culture the Specificity of Film on Television: The

ORBIT-OnlineRepository ofBirkbeckInstitutionalTheses Enabling Open Access to Birkbeck’s Research Degree output Celluloid Television Culture The Specificity of Film on Television: the Action-adventure Text as an Example of a Production and Textual Strategy, 1955 – 1978. https://eprints.bbk.ac.uk/id/eprint/40025/ Version: Full Version Citation: Sexton, Max (2013) Celluloid Television Culture The Speci- ficity of Film on Television: the Action-adventure Text as an Example of a Production and Textual Strategy, 1955 – 1978. [Thesis] (Unpublished) c 2020 The Author(s) All material available through ORBIT is protected by intellectual property law, including copy- right law. Any use made of the contents should comply with the relevant law. Deposit Guide Contact: email Celluloid Television Culture The Specificity of Film on Television: the Action-adventure Text as an Example of a Production and Textual Strategy, 1955 – 1978. Max Sexton A thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy, Birkbeck, University of London, 2012. Declaration I hereby declare that the thesis presented by me for examination of the PhD degree is solely my own work, other than where I have clearly indicated. Birkbeck, University of London Abstract of Thesis (5ST) Notes for Candidate: 1. Type your abstract on the other side of this sheet. 2. Use single-spacing typing. Limit your abstract to one side of the sheet. 3. Please submit this copy of your abstract to the Research Student Unit, Birkbeck, University of London, Registry, Malet Street, London, WC1E 7HX, at the same time as you submit copies of your thesis. 4. This abstract will be forwarded to the University Library, which will send this sheet to the British Library and to ASLIB (Association of Special Libraries and Information Bureaux) for publication to Index to Theses . -

Sands End Revisited a Local History Guide

SANDS END REvisitED A Local HISToRy GuIDE We found useful information at the Archive and Local History centre in Hammersmith. There were people that came into school and helped us with our research because they had been residents in Sands End or pupils at Langford many years ago. We also went to Elizabeth Barnes Court Old People’s home to hear more stories and memories of people who knew Sands End in the past. Some of the places in Sands End are named after people that lived here, for example Bagley’s Lane, is named after the Bagley family, locally well known for market gardening and were called the ‘Kings of Fulham’. Elaysha This local history guide about the Sands End area, has been compiled by Y6 from Langford Primary school. Working in partnership with Hammersmith and Fulham Urban Studies Centre, LBHF’s Archives and Local History Centre, and local interest group Sands End Revisited, Oak class became ‘History Detectives’ and were taken back in time to discover the stories of Sands End and the changes that have taken place over the years. By visiting local landmarks, such as the Community Centre on Broughton Road - which was once the old Sunlight laundry - examining old photos at the Archives, and sharing the memories of former local residents and pupils of Langford School, the children discovered a wealth of information, learnt about the changes that have taken place over the years and tried to uncover any secrets about the local area. The stories presented here are a mixture of fact, personal experience, and maybe a little bit of urban myth thrown in to really get you thinking! Thanks to Heritage Lottery Fund for the grant to produce the project. -

File Stardom in the Following Decade

Margaret Rutherford, Alastair Sim, eccentricity and the British character actor WILSON, Chris Available from the Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive (SHURA) at: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/17393/ A Sheffield Hallam University thesis This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Please visit http://shura.shu.ac.uk/17393/ and http://shura.shu.ac.uk/information.html for further details about copyright and re-use permissions. Sheffield Hallam University Learning and IT Services Adsetts Centre City Campus 2S>22 Sheffield S1 1WB 101 826 201 6 Return to Learning Centre of issue Fines are charged at 50p per hour REFERENCE Margaret Rutherford, Alastair Sim, Eccentricity and the British Character Actor by Chris Wilson A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Sheffield Hallam University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy September 2005 I should like to dedicate this thesis to my mother who died peacefully on July 1st, 2005. She loved the work of both actors, and I like to think she would have approved. Abstract The thesis is in the form of four sections, with an introduction and conclusion. The text should be used in conjunction with the annotated filmography. The introduction includes my initial impressions of Margaret Rutherford and Alastair Sim's work, and its significance for British cinema as a whole.