Historical Paper No.3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Biennial Review 1969/70 Bedford Institute Dartmouth, Nova Scotia Ocean Science Reviews 1969/70 A

(This page Blank in the original) ii Bedford Institute. ii Biennial Review 1969/70 Bedford Institute Dartmouth, Nova Scotia Ocean Science Reviews 1969/70 A Atlantic Oceanographic Laboratory Marine Sciences Branch Department of Energy, Mines and Resources’ B Marine Ecology Laboratory Fisheries Research Board of Canada C *As of June 11, 1971, Department of Environment (see forward), iii (This page Blank in the original) iv Foreword This Biennial Review continues our established practice of issuing a single document to report upon the work of the Bedford Institute as a whole. A new feature introduced in this edition is a section containing four essays: The HUDSON 70 Expedition by C.R. Mann Earth Sciences Studies in Arctic Marine Waters, 1970 by B.R. Pelletier Analysis of Marine Ecosystems by K.H. Mann Operation Oil by C.S. Mason and Wm. L. Ford They serve as an overview of the focal interests of the past two years in contrast to the body of the Review, which is basically a series of individual progress reports. The search for petroleum on the continental shelves of Eastern Canada and Arctic intensified considerably with several drilling rigs and many geophysical exploration teams in the field. To provide a regional depository for the mandatory core samples required from all drilling, the first stage of a core storage and archival laboratory was completed in 1970. This new addition to the Institute is operated by the Resource Administration Division of the Department of Energy, Mines & Resources. In a related move the Geological Survey of Canada undertook to establish at the Institute a new team whose primary function will be the stratigraphic mapping of the continental shelf. -

HALIFAX HIGHLIGHTS | Issue 6 1

HALIFAX HIGHLIGHTS | Issue 6 1 Issue 6 July 31, 2013 HALIFAX HIGHLIGHTS Introducing you to Halifax, and helping you get ready for the fall Join us on social media for the most up to date news and events! MUSEUMS AND HISTORY One of the things that visitors and newcomers often Halifax Citadel find striking about Halifax is its sense of history. Hali- 5425 Sackville St fax is one of Canada’s oldest cities, and there are This national historic site is open year-round (though ser- many museums and historic sites that celebrate vari- vices and interpretation are only available from May to ous aspects of Halifax’s past that you should be sure October). The hill, now a very visible and well-known tour- to visit while you are here. In this issue, we hope to ist attraction, was the site of Fort George and the centre of highlight some of these historic places. Halifax’ elaborate defensive system for about one hundred If you want to learn more about Halifax’s story, be -fifty years. Today, costumed interpreters offer tours and sure to visit the Halifax Regional Municipality’s brief explanations of life in the fort as it would have been in the history on their website: http://www.halifax.ca/ year 1869. community/history.html The Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21 1055 Marginal Road Pier 21 was a passenger terminal used to process immi- grants to Canada arriving via ocean liner from 1928 to 1971. Opened as a national museum in 1999, Pier 21 cele- brates the story of Canadian immigration, going back to 1867 and as far up as the present day. -

Peacekeepers Parade

The Bosn’s Call Volume 24, No. 3, Autumn 2017 PEACEKEEPERS PARADE Pictured above is the Colour Party from the Calgary Naval Veterans Association at the Peace- keepers’ Parade held on Sunday, August 13th. Left to Right ~ Cal Annis, Bill Bethell, Art Jor- genson and Master-at-Arms Eric Kahler. Calgary Naval Veterans Association • www.cnva.ca CALGARY NAVAL VETERANS ASSOCIATION Skipper’s www.cnva.ca Autumn 2017 | Corvette Club: 2402 - 2A Street SE, Calgary, AB T2G 4Z2 Log [email protected] ~ 403-261-0530 ~ Fax 403-261-0540 n EXECUTIVE Paris Sahlen, CNVA President F PAST PRESIDENT • Art JORGENSON – 403-281-2468, [email protected] – Charities, Communication. The Bosn’s Call The Bosn’s hope everyone has had a nice warm summer F PRESIDENT • Paris SAHLEN, CD – 403-252-4532, RCNA, HMCS Calgary Liaison, Charities, Stampede. with a little smoke thrown in. Here is an update F EXECUTIVE VICE-PRESIDENT • Ken MADRICK Charities, Honours on the different activities the Club has been do- & Awards, Financial Statements, Galley Vice-Admiral. I ing this year so far. F VICE-PRESIDENT • Tom CONRICK • Sick & Visiting, Colonel Belcher, Charities, Honours & Awards. We still have Remembrance Day, our trip to Banff and our New Year’s Levee. The Club will F TREASURER • Anita VON – 403-240-1967. be closed December 23rd. One other thing—it F SECRETARY • Laura WEAVER. would be nice if we asked our Red Seal chefs if n DIRECTORS there is anything they need help with before leav- F Cal ANNIS – 403-938-0955 • Honours & Awards, Galley Till. ing the Club. -

Corporate Plan Summary, the Quarterly June 22, 2017

2018–2019 — DEFENCE CONSTRUCTION CANADA 2022–2023 CORPORATE PLAN INCLUDING THE OPERATING AND SUMMARY CAPITAL BUDGETS FOR 2018–2019 AN INTRODUCTION TO DEFENCE CONSTRUCTION CANADA Defence Construction Canada (DCC) is a unique maintenance work. Others are more complex with organization in many ways—its business model high security requirements. combines the best characteristics from both the private and public sector. To draw a comparison, DCC has site offices at all active Canadian Armed DCC’s everyday operations are similar to those of Forces (CAF) establishments in Canada and abroad, as a civil engineering consultancy firm. However, as required. Its Head Office is in Ottawa and it maintains a Crown corporation, it is governed by Part X of five regional offices (Atlantic, Quebec, Ontario, Schedule III to the Financial Administration Act. Its Western and National Capital Region), as well as 31 key Client-Partners are the Assistant Deputy Minister site offices located at Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) Infrastructure and Environment (ADM IE) Group at bases, wings, and area support units. The Corporation the Department of National Defence (DND) and the currently employs about 900 people. Communications Security Establishment (CSE). The Corporation also provides services to Shared Services As a Crown corporation, DCC complies with Canada relating to the expansion of the electronic Government of Canada legislation, such as the data centre at CFB Borden. DCC employees do not do Financial Administration Act, Official Languages the hands-on, hammer-and-nails construction work Act, Access to Information Act and Employment at the job site. Instead, as part of an organization that Equity Act, to name a few. -

Trident Fury 2020

• CANADIAN MILITARY’S TRUSTED NEWS SOURCE • NEED Volume 65 Number 48 | December 7, 2020 MORE SPACE? STILL TAKING DONATIONS! newspaper.comnewwsspapaper.com 2020 NDWCC MARPAC NEWSEWWS CFBCFCFB Esquimalt,EsEsqqu Victoria, B.C. NOW OPEN! 4402 Westshore Parkway, Victoria DONATE NOW THRU E-PLEDGE (778) 817-1293 • eliteselfstorage.ca TRIDENT FURY 2020 MS Cole Wood, from the Mine Countermeasures Diving Team, checks equipment in the Containerized Diving System Workshop on board HMCS Whitehorse during Exercise Trident Fury 2020. Beautiful smiles We proudly serve the start here! Island Owned and Operated Canadian Forces Community since 1984. As a military family we understand your cleaning needs during ongoing VIEW OUR FLYER Capital Park service, deployment and relocation. www.mollymaid.ca Dental IN THIS PAPER WEEKLY! 250-590-8566 CapitalParkDental.com (250) 744-3427 check out our newly renovated esquimalt store Français aussi ! Suite 110, 525 Superior St, Victoria [email protected] 2 • LOOKOUT CANADIAN MILITARY’S TRUSTED NEWS SOURCE • CELEBRATING 76 YEARS PROVIDING RCN NEWS December 7, 2020 Force Preservation and Generation IN A PANDEMIC SLt K.B. McHale-Hall Dalhousie University in Halifax, N.S., for medical essential activities to be conducted, and the potential MARPAC Public Affairs school, LCdr Drake jokingly remarks of the common- for members to spend the quarantine period in their alities. “I don’t have any shoes named after me yet, but homes should set household requirements be met. “People first, mission always.” there’s still time.” The strict protocol of a full quarantine eliminates all Amidst a global pandemic, this core philosophy of His career began in the Naval Reserves serving as interactions with others. -

MWO Martin (Smiley) Nowell, CD After 41 + Years of Loyal and Dedicated

MWO Martin (Smiley) Nowell, CD After 41 + years of loyal and dedicated service to the CAF and the CME branch, MWO Nowell will be retiring on the 12th of August 2015. MWO Nowell was born in Winnipeg, Manitoba in 1956. He joined the CF on the 13 of June 1974 as a Field Engineer. On completion of basic training and QL3 course Pte Nowell was posted to 3 Field Squadron, CFB Chilliwack. After almost five years in Chilliwack, Cpl Nowell was posted to CFB Shilo in May 1979. After seeing the light Cpl Nowell remustered to a Water sewage and POL tech in 1983 and was back in CFSME for his QL3 course. Upon completion of his course Cpl Nowell was posted to CFB Portage La Prairie. A quick 3 year posting in Portage Cpl Nowell was packing up and moving to CFB Cold Lake. During his posting to Cold Lake, in Dec 1990 Cpl Nowell had his first deployment to UNDOF (Golan Heights) for a six month tour. On the completion of his tour Cpl Nowell was on the move again being posted back to 1CER CFB Chilliwack in 1991. Within a year from returning from the Golan Heights Cpl Nowell was being deployed to Kuwait in April for a nine month tour. Upon returning from tour he was on a summer exercise in Wainwright AB. After the exercise he was on the move again in 1993 to CFB Winnipeg for his first posting there. During his posting to Winnipeg he was deployed to Somali for a six month tour. -

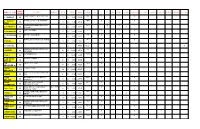

Name of Plan Wing Span Details Source Area Price Ama Ff Cl Ot Scale Gas Rubber Electric Other Glider 3 View Engine Red. Ot C

WING NAME OF PLAN DETAILS SOURCE AREA PRICE AMA POND RC FF CL OT SCALE GAS RUBBER ELECTRIC OTHER GLIDER 3 VIEW ENGINE RED. OT SPAN COMET MODEL AIRPLANE CO. 7D4 X X C 1 PURSUIT 15 3 $ 4.00 33199 C 1 PURSUIT FLYING ACES CLUB FINEMAN 80B5 X X 15 3 $ 4.00 30519 (NEW) MODEL AIRPLANE NEWS 1/69, 90C3 X X C 47 PROFILE 35 SCHAAF 5 $ 7.00 31244 X WALT MOONEY 14F7 X X X C A B MINICAB 20 3 $ 4.00 21346 C L W CURLEW BRITISH MAGAZINE 6D6 X X X 15 2 $ 3.00 20416 T 1 POPULAR AVIATION 9/28, POND 40E5 X X C MODEL 24 4 $ 5.00 24542 C P SPECIAL $ - 34697 RD121 X MODEL AIRPLANE NEWS 4/42, 8A6 X X C RAIDER 68 LATORRE 21 $ 23.00 20519 X AEROMODELLO 42D3 X C S A 1 38 9 $ 12.00 32805 C.A.B. GY 20 BY WALT MOONEY X X X 20 4 $ 6.00 36265 MINICAB C.W. SKY FLYER PLAN 15G3 X X HELLDIVER 02 15 4 $ 5.00 35529 C2 (INC C130 H PLAMER PLAN X X X 133 90 $ 122.00 50587 X HERCULES QUIET & ELECTRIC FLIGHT INT., X CABBIE 38 5/06 6 $ 9.00 50413 CABIN AEROMODELLER PLAN 8/41, 35F5 X X 20 4 $ 5.00 23940 BIPLANE DOWNES CABIN THE OAKLAND TRIBUNE 68B3 X X 20 3 $ 4.00 29091 COMMERCIAL NEWSPAPER 1931 Indoor Miller’s record-holding Dec. 1979 X Cabin Fever: 40 Manhattan Cabin. -

1. Canadian Marine SCIENCE from Before Titanic to the Establishment of the Bedford Institute of Oceanography in 1962 Eric L. Mills

HISTORICAL ROOTS 1. CANADIAN MARINE SCIENCE FROM BEFORE TITANIC TO THE ESTABLISHMENT OF THE BEDFORD INSTITUTE OF OCEANOGRAPHY IN 1962 Eric L. Mills SUMMARY Beginning in the early 1960s, the Bedford Institute of Oceanography consolidated marine sciences and technologies that had developed separately, some of them since the late 19th century. Marine laboratories, devoted mainly to marine biology, were established in 1908 in St. Andrews, New Brunswick, and Nanaimo, British Columbia, and it was in them that Canada’s first studies in physical oceanography began in the early 1930s and became fully established after World War II. Charting and tidal observation developed separately in post-Confederation Canada, beginning in the last two decades of the 19th century, and becoming united in the Canadian Hydrographic Service in 1924. For a number of scientific and political reasons, Canadian marine sciences developed most rapidly after World War II (post-1945), including work in the Arctic, the founding of graduate programs in oceanography on both Atlantic and Pacific coasts, the reorientation of physical oceanography from the federal Fisheries Research Board to the federal Department of Mines and Technical Surveys, increased work on marine geology and geophysics, and eventually the founding of the Bedford Institute of Oceanography, which brought all these fields together. Key words: Canadian marine science, Atlantic and Pacific biological stations, charting, tides, hydrography, post-World War II developments, origin of BIO. E-mail: [email protected] The Bedford Institute of Oceanography (BIO) opened formally in 1962 Europe decades before. The result, achieved with the help of university (Fig. 1), bringing together scientists and technologists who had worked in biologists, was an organizational structure, the Board of Management of fields as diverse as physical oceanography, hydrographic charting, marine the Biological Station (became the Biological Board of Canada in 1912), geology, and marine ecology. -

Convoy Cup Mini-Offshore Race September 12, 2020

Notice of Race Convoy Cup Mini-Offshore Race September 12, 2020 1. Organizing Authority: These races are hosted by the Dartmouth Yacht Club of Dartmouth, Nova Scotia. 2. Objectives: The Convoy Cup Ocean Race offers racing and cruising yachts an opportunity to participate in an ocean race to commemorate the links that formed between the province of Nova Scotia and the countries of Europe during the two world wars. Halifax was the congregation point for hundreds of naval vessels and supply ships that formed convoys to transport the necessities of life across the Atlantic Ocean; this race is dedicated to the memory of all those men and women in the navy and merchant marine service who sailed in those convoys. 3. Rules: Racing will be governed by the Racing Rules of Sailing 2017-2020 (RRS), the prescriptions of the Canadian Yachting Association and this Notice of Race except as modified by the Sailing Instructions. Dartmouth Yacht Club Race Committee (RC) will have final authority on all matters. 4. Description: Normally the Convoy Cup is an overnight 100 n/m ocean race and a Basin Race is also held. This season is quite different due to the COVID 19 pandemic so the event this year has been changed to a mini-offshore race. The Convoy Cup Mini-Offshore Race will be comprised of 1 race of approximately 30 n/m (course and distances may be adjusted according to forecast winds and conditions). 5. Start date, course and finish: The races will commence September 12, 2020 at 1200 at a start line established between the Navy Island buoy HY2 (Mark 11on the DYC course card) and the RC flag on the Race Committee boat passing either side of George’s Island outbound only, and proceeding to HB, port rounding and return keeping George’s Island to starboard, to finish at the CSS Acadia dock, at in a line projected from the edge of the wharf, which is closest to the Last Steps Memorial. -

Fucus Gardneri Using Gamma-Ray Spectroscopy

Determination of 131I Uptake in Fucus Gardneri Using Gamma-Ray Spectroscopy Determination de 1'Accumulation de I dans Fucus Gardneri par Spectroscopie Gamma A thesis submitted to the Division of Graduate Studies of the Royal Military College of Canada By Kristine Margaret Mattson In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Applied Science in Nuclear Engineering August 2011 © This thesis may be used within the Department of National Defence, but copyright for open publication remains the property of the author. Library and Archives Bibliotheque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du in Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-83402-2 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-83402-2 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distrbute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. -

ACTION STATIONS! Volume 37 - Issue 1 Winter 2018

HMCS SACKVILLE - CANADA’S NAVAL MEMORIAL ACTION STATIONS! Volume 37 - Issue 1 Winter 2018 Action Stations Winter 2018 1 Volume 37 - Issue 1 ACTION STATIONS! Winter 2018 Editor and design: Our Cover LCdr ret’d Pat Jessup, RCN Chair - Commemorations, CNMT [email protected] Editorial Committee LS ret’d Steve Rowland, RCN Cdr ret’d Len Canfield, RCN - Public Affairs LCdr ret’d Doug Thomas, RCN - Exec. Director Debbie Findlay - Financial Officer Editorial Associates Major ret’d Peter Holmes, RCAF Tanya Cowbrough Carl Anderson CPO Dean Boettger, RCN webmaster: Steve Rowland Permanently moored in the Thames close to London Bridge, HMS Belfast was commissioned into the Royal Photographers Navy in August 1939. In late 1942 she was assigned for duty in the North Atlantic where she played a key role Lt(N) ret’d Ian Urquhart, RCN in the battle of North Cape, which ended in the sinking Cdr ret’d Bill Gard, RCN of the German battle cruiser Scharnhorst. In June 1944 Doug Struthers HMS Belfast led the naval bombardment off Normandy in Cdr ret’d Heather Armstrong, RCN support of the Allied landings of D-Day. She last fired her guns in anger during the Korean War, when she earned the name “that straight-shooting ship”. HMS Belfast is Garry Weir now part of the Imperial War Museum and along with http://www.forposterityssake.ca/ HMCS Sackville, a member of the Historical Naval Ships Association. HMS Belfast turns 80 in 2018 and is open Roger Litwiller: daily to visitors. http://www.rogerlitwiller.com/ HMS Belfast photograph courtesy of the Imperial -

For an Extra $130 Bucks…

For an Extra $130 Bucks…. Update On Canada’s Military Financial Crisis A VIEW FROM THE BOTTOM UP Report of the Standing Senate Committee on National Security and Defence Committee Members Sen. Colin Kenny – Chair Sen. J. Michael Forrestall – Deputy Chair Sen. Norman K. Atkins Sen. Tommy Banks Sen. Jane Cordy Sen. Joseph A. Day Sen. Michael A. Meighen Sen. David P. Smith Sen. John (Jack) Wiebe Second Session Thirty-Seventh Parliament November 2002 (Ce rapport est disponible en français) Information regarding the committee can be obtained through its web site: http://sen-sec.ca Questions can be directed to: Toll free: 1-800-267-7362 Or via e-mail: The Committee Clerk: [email protected] The Committee Chair: [email protected] Media inquiries can be directed to: [email protected] For an Extra 130 Bucks . Update On Canada’s Military Financial Crisis A VIEW FROM THE BOTTOM UP • Senate Standing Committee on National Security and Defence November, 2002 MEMBERSHIP 37th Parliament – 2nd Session STANDING COMMITTEE ON NATIONAL SECURITY AND DEFENCE The Honourable Colin Kenny, Chair The Honourable J. Michael Forrestall, Deputy Chair And The Honourable Senators: Atkins Banks Cordy Day Meighen Smith* (Not a member of the Committee during the period that the evidence was gathered) Wiebe *Carstairs, P.C. (or Robichaud, P.C.) *Lynch-Staunton (or Kinsella) *Ex Officio Members FOR AN EXTRA $130 BUCKS: UPDATE ON CANADA’S MILITARY FINANCIAL CRISIS A VIEW FROM THE BOTTOM UP TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 7 MONEY ISN’T EVERYTHING, BUT . ............................................ 9 WHEN FRUGAL ISN’T SMART ....................................................