Download Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gerrit Dou's Enchanting Trompe- L'oeil

Volume 7, Issue 1 (Winter 2015) Gerrit Dou’s Enchanting Trompe- l’Oeil : Virtuosity and Agency in Early Modern Collections Angela Ho [email protected] Recommended Citation: Angela Ho, “Gerrit Dou’s Enchanting Trompe- l’Oeil : Virtuosity and Agency in Early Modern Collections,” JHNA 7:1 (Winter 2015), DOI: 10.5092/jhna.2015.7.1.1 Available at https://jhna.org/articles/gerrit-dous-enchanting-trompe-loeil-virtuosity-agen- cy-in-early-modern-collections/ Published by Historians of Netherlandish Art: https://hnanews.org/ Republication Guidelines: https://jhna.org/republication-guidelines/ Notes: This PDF is provided for reference purposes only and may not contain all the functionality or features of the original, online publication. This is a revised PDF that may contain different page numbers from the previous version. Use electronic searching to locate passages. This PDF provides paragraph numbers as well as page numbers for citation purposes. ISSN: 1949-9833 JHNA 1:1 (Winter 2009) 1 GERRIT DOU’S ENCHANTING TROMPE L’OEIL: VIRTUOSITY AND AGENCY IN EARLY MODERN COLLECTIONS Angela Ho This paper focuses on Painter with Pipe and Book (ca. 1650) by Gerrit Dou, a painter much admired by an exclusive circle of elite collectors in his own time. By incorporating a false frame and picture curtain, Dou transformed this work from a familiar “niche picture” into a depiction of a painting composed in his signature format. Drawing on anthropologist Alfred Gell’s concepts of enchantment and art nexus, I analyze how such a picture would have mediated the interactions between artist, owner, and viewer, enabling each agent to project his identity and shape one another’s response. -

Exceptional Examples of the Masters of Etching and Engraving : the Print Collection of the Late J. Harsen Purdy, of New York

EXCEPTIONAL EXAMPLES OF THE MASTERS OF ETCHINa AND ENGRAVING THE PRINT COLLECTION OF THE LATE J. HARSEN PURDY, of new york city TO BE SOLD AT UNRESTRICTED PUBLIC SALE ON TUESDAY AND WEDNESDAY EVENINGS APRIL 10th and 11th, 1917 UNDER THE MANAGEMENT OF THE AMERICAN ART ASSOCIATION AMERICAN ART GALLERIES MADISON SQUARE SOUTH NEW YORK CITY smithsoniaM INSTITUTION 3i< 7' THE AMERICAN ART ASSOCIATION DESIGNS ITS CATALOGUES AND DIRECTS ALL DETAILS OF ILLUSTRATION TEXT AND TYPOGRAPHY ON PUBLIC EXHIBITION AT THE AMERICAN ART GALLERIES MADISON SQUARE SOUTH, NEW YORK ENTRANCE, 6 EAST 23rd STREET BEGINNING THURSDAY, APRIL 5th, 1917 MASTERPIECES OF ENGRAVERS AND ETCHERS THE PRINT COLLECTION OF THE LATE J. HARSEN PURDY, of new york city TO BE SOLD AT UNRESTRICTED PUBLIC SALE BY ORDER OF ALBERT W. PROSS, ESQ., AND THE NEW YORK TRUST COMPANY, AS EXECUTORS ON TUESDAY AND WEDNESDAY EVENINGS APRIL 10th and 11th, 1917 AT 8:00 O'CLOCK IN THE EVENINGS AT THE AMERICAN ART GALLERIES ALBRECHT DURER, ENGRAVING Knight, Death and the Devil [No. 69] EXCEPTIONAL EXAMPLES OF THE MASTERS OF ETCHING AND ENGRAVING THE PRINT COLLECTION OF THE LATE J. HARSEN PURDY, of new york city TO BE sold at unrestricted PUBLIC SALE BY ORDER OF ALBERT W. PROSS, ESQ., AND THE NEW YORK TRUST COMPANY, AS EXECUTORS ON TUESDAY AND WEDNESDAY, APRIL 10th AND 11th AT 8:00 O'CLOCK IN THE EVENINGS THE SALE TO BE CONDUCTED BY MR. THOMAS E. KIRBY AND HIS ASSISTANTS, OF THE AMERICAN ART ASSOCIATION, Managers NEW YORK CITY 1917 ——— ^37 INTRODUCTORY NOTICE REGARDING THE PRINT- COLLECTION OF THE LATE MR. -

Wallerant VAILLANT

Neil Jeffares, Dictionary of pastellists before 1800 Online edition VAILLANT, Wallerant colour than the earlier drawings, and it seems Lille 30.V.1623 – Amsterdam 28.VIII.1677 likely that this change in technique was The eldest of five artist brothers, Wallerant encouraged by the availability of better materials Vaillant (also spelt Walrand Vailjant, etc.) was than the artist had previously been able to obtain born in Lille. Vaillant’s family, who were or manufacture. It seems unlikely to be Protestant, left Lille for Amsterdam around 1642, coincidence that Vaillant and Nanteuil (q.v.) both although Wallerant had joined the studio of turned to this medium in Paris at the same time. Erasmus Quellin II in Antwerp in 1639. Vaillant Bibliography made portraits and still lifes in oil, including a Barrow 1735, s.v. Crayons, citing Browne; series of highly finished self-portraits. He is also Bénézit; Bergmans 1936–38; Brieger 1921; known to have produced numerous black chalk Browne 1675, p. 25f; Dechaux & al. 1995; Ger portraits by around 1650 (one, in Berlin, is dated Luijten, in Grove; Mariette 1851–60, s.v. Robert 1642); some of these early sheets may have used (Le Prince); Meder 1919, p. 138; Pilkington 1852; a very limited range of pastel. His earliest known Ratouis de Limay 1946; Rogeaux 2001; etchings are dated 1656. J.732.111 Gosuinus van BUYTENDYCK (1585– Rotterdam 1976; Shelley 2002; Thieme & Becker; 1661), predikant te Dordrecht, m/u, 1650 He travelled widely: in 1658 he was recorded Vandalle 1937; Wessely 1865, 1881 in Heidelberg, and in the same year he attended ~grav. -

Kiállítás a Keresztény Múzeum Gyűjteményéből 2004

(1609 – 1690) Kiállítás a Keresztény Múzeum gyűjteményéből 2004. június 8 – szeptember 30. Exhibition from the collection of the Christian Museum June 8 – September 30, 2004 A kiállítást rendezték és a katalógust írták Curators of the exhibition and authors of the catalogue Iványi Bianca, Juhász Sándor Köszönet a kutatásban nyújtott segítségért • Thanks for research assistance Huigen Leeflang, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam Klaus de Rijk, Royal Netherlands Embassy, Budapest Jef Schaeps, Printroom of Leiden University, Leiden Gary Schwartz, CODART, Amsterdam Leslie Schwartz, Teylers Museum, Haarlem Külön köszönet • Special thanks Zentai Loránd, Szépművészeti Múzeum, Budapest Angol fordítás • English translation Mezei Elmira Katalógus terv • Catalogue design Barák Péter, Premierlap – Arbako Stúdió, Budapest Borító terv • Cover design Suhai Dóra A kiállítás támogatói • Sponsors of the exhibition A katalógus támogatója • Sponsor of the catalogue Nemzeti Kulturális Alapprogram Kiadó • Publisher Keresztény Múzeum, Esztergom Felelős kiadó • Editor in chief Cséfalvay Pál Copyright © Iványi Bianca, Juhász Sándor, 2004 Copyright © Keresztény Múzeum, 2004 ISBN 963 7129 13 8 INTRODUCTION Hallmarked by such outstanding talents as Rembrandt and Vermeer, the seventeenth century was the Golden Age of Dutch art. Antoni Waterloo (1609–1690) was one of the successful artists of that period; today, however, his name is hardly known to the wider public. Because of the modest number of paintings that are verifiably his, we must look to his graphics – to the almost 140 etchings and several drawings that are left to us – to evaluate his art. Waterloo belongs to the so-called peintre-graveur group of artists; a painter who etched his own original compositions instead of executing reproductions, like several other artists did. -

HNA November 2017 Newsletter

historians of netherlandish art NEWSLETTER AND REVIEW OF BOOKS Dedicated to the Study of Netherlandish, German and Franco-Flemish Art and Architecture, 1350-1750 Vol. 34, No. 2 November 2017 Peter Paul Rubens, Centaur Tormented by Peter Paul Rubens, Ecce Homo, c. 1612. Cupid. Drawing after Antique Sculpture, State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg 1600/1608. Wallraf-Richartz-Museum, © The State Hermitage Museum, Cologne © Rheinisches Bildarchiv Köln St. Petersburg 2017 Exhibited in Peter Paul Rubens: The Power of Transformation. Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, October 17, 2017 – January 21, 2018 Städel Museum, Frankfurt, February 8 – May 21, 2018. HNA Newsletter, Vol. 23, No. 2, November 2006 1 historians of netherlandish art www.hnanews.org E-Mail: [email protected] Historians of Netherlandish Art Offi cers President – Paul Crenshaw (2017-2021) Providence College Department of Art History 1 Cummingham Square Providence RI 02918-0001 Vice-President – Louisa Wood Ruby (2017-2021) The Frick Collection and Art Reference Library 10 East 71 Street New York NY 10021 Treasurer – David Levine Southern Connecticut State University 501 Crescent Street New Haven CT 06515 European Treasurer and Liaison - Fiona Healy Seminarstrasse 7 D-55127 Mainz Germany Contents President's Message .............................................................. 1 In Memoriam ......................................................................... 2 Board Members Personalia ............................................................................... 4 Arthur -

Anthonie Waterloo

Anthonie Waterloo Anthonie Waterloo | Tekeningen en Schilderijen Anthonie Waterloo Aliases: Antonie Waaterloo; Anthonie Waterlo; Anthonie Waterloo; Antonie Waterloo; Anthonis Waterlouw van Ryssel, born Lille, bapt 6 May 1609; d Utrecht, 23 Oct 1690. Antoni Waterloo (Lille, 1609 - Utrecht, 1690) was a painter, publisher, draughtsman, and an acclaimed etcher in his time. He is very little known to the general audience, despite the fact that actually quite a bit is known about his life, although information on him is scattered. Waterloo was born in 1609 in Lille, probably a few days before his baptism on 6 May 1609, as a son of the cloth-cutter Caspar Waterloo. He was named after his grandfather, Antoni Waterloo. We do not know precisely how Waterloo came to Amsterdam in 1621. Before and during the Spanish-Dutch conflict in 1621, many Flemish people went to Holland, preferring Dutch rule, which supported tolerance, to that of Spain. Waterloo is not known to have had any teacher, and he said to have been self- taught, but certainly the many artists in his family and among his friends introduced him to the techniques of art. His mother was Magdalena Vaillant, aunt of Wallerant Vaillant, the best-known of the famous Vaillant family of etchers. In 1640 Waterloo married Catharyna Stevens van der Dorp who was the widow of painter and dealer Elias Homis. Waterloo moved about considerably during his life. He made the traditional Rhine voyage. About 1660 he travelled to Hamburg, Altona, Blankenese, Holstein, Bergdorf, Lüneburg and Gdansk. Maybe he went to south and possibly visited Italy. -

Old Master Prints

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt6n39n8g8 Online items available Old Master Prints Processed by Grunwald Center for the Graphic Arts, UCLA Hammer Museum staff; machine-readable finding aid created by Layna White Grunwald Center for the Graphic Arts UCLA Hammer Museum University of California, Los Angeles 10899 Wilshire Blvd. Los Angeles, California 90024-4201 Phone: (310) 443-7078 Fax: (310) 443-7099 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.hammer.ucla.edu © 2003 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Old Master Prints 1 Old Master Prints Grunwald Center for the Graphic Arts, UCLA Hammer Museum University of California, Los Angeles Los Angeles, California Contact Information Grunwald Center for the Graphic Arts UCLA Hammer Museum University of California, Los Angeles 10899 Wilshire Blvd. Los Angeles, California 90024-4201 Phone: (310) 443-7078 Fax: (310) 443-7099 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.hammer.ucla.edu Processed by: Grunwald Center for the Graphic Arts, UCLA Hammer Museum staff Date Completed: 2/21/2003 Encoded by: Layna White © 2003 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: Old Master Prints Repository: Grunwald Center for the Graphic Arts, UCLA Hammer Museum Los Angeles, CA 90024 Language: English. Publication Rights For publication information, please contact Susan Shin, Grunwald Center for the Graphic Arts, [email protected] Preferred Citation [Identification of item], Collection of the Grunwald Center for the Graphic Arts, UCLA. [Item credit line, if given] Notes In 15th-century Europe, the invention of the printed image coincided with both the wide availability of paper and the invention of moveable type in the West. -

Michael Sweerts (1618-1664) and the Academic Tradition

ABSTRACT Title of Document: MICHAEL SWEERTS (1618-1664) AND THE ACADEMIC TRADITION Lara Rebecca Yeager-Crasselt, Doctor of Philosophy, 2013 Directed By: Professor Arthur K. Wheelock, Jr., Department of Art History and Archaeology This dissertation examines the career of Flemish artist Michael Sweerts (1618-1664) in Brussels and Rome, and his place in the development of an academic tradition in the Netherlands in the seventeenth century. Sweerts demonstrated a deep interest in artistic practice, theory and pedagogy over the course of his career, which found remarkable expression in a number of paintings that represent artists learning and practicing their profession. In studios and local neighborhoods, Sweerts depicts artists drawing or painting after antique sculpture and live models, reflecting the coalescence of Northern and Southern attitudes towards the education of artists and the function and meaning of the early modern academy. By shifting the emphasis on Sweerts away from the Bamboccianti – the contemporary group of Dutch and Flemish genre painters who depicted Rome’s everyday subject matter – to a different set of artistic traditions, this dissertation is able to approach the artist from new contextual and theoretical perspectives. It firmly situates Sweerts within the artistic and intellectual contexts of his native Brussels, examining the classicistic traditions and tapestry industry that he encountered as a young, aspiring artist. It positions him and his work in relation to the Italian academic culture he experienced in Rome, as well as investigating his engagement with the work of the Flemish sculptor François Duquesnoy (1597-1643) and the French painter Nicholas Poussin (1594-1665). The breadth of Sweerts’ artistic and academic pursuits ultimately provide significant insight into the ways in which the Netherlandish artistic traditions of naturalism and working from life coalesced with the theoretical and practical aims of the academy. -

A Larder Still-Life with a Cockerel Hanging from a Hook and A

A larder still-life with a cockerel hanging from a hook POA and a sleeping boy with game and a gun at the window REF:- 365306 Artist: Circle of WALLERANT VAILLANT Height: 109 cm (42 1/1") Width: 89 cm (35") Framed Height: 137.3 cm (54") Framed Width: 117 cm (46") 1 https://johnbennettfinepaintings.com/a-larder-stilllife-with-a-cockerel-hanging-from-a-hook- and-a 01/10/2021 Short Description Wallerant Vaillant was a Dutch Golden Age painter and although a painter in oils, is probably best known now for being one of the first to utilise the schraapkunst - mezzotint - technique. He born in Lille (which was Flemish until being taken by Louis XIV in 1668) on 30th May 1623, one of five boys who all became painters or engravers although one of them later joined the church and another became a merchant. In 1639 he was a pupil of Erasmus Quellinus II (1607-1678) in Antwerp but by 1643 he was living with his parents in Amsterdam remaining in that city, apart from a stay in Middleburg from 1647-9 where he became a member of the Guild of St Luke, until 1658 when he travelled with his brother Bernard to Frankfurt and Heidelburg. In 1649 he painted a portrait of Jan Six, a wealthy Amsterdam merchant who had previously been painted and etched by Rembrandt and during this stage of his career in Amsterdam he was not only working on oils but also producing life-size chalk portraits and some etchings. Stylistically, Vaillant was influenced by the important Amsterdam portrait painter Bartholomeus van der Helst (1613-1670) and then later, during his five years in Paris, by the French School. -

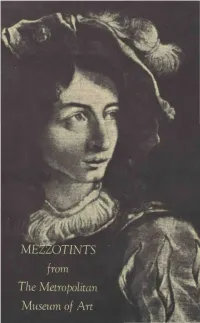

A from the Metropolitan Museum Of

A from The Metropolitan Museum of Art t Cover: The Standard Bearer (detail) by Prince Rupert (1619-1682) alter Pietro della Vecchia MEZZOTINTS from The Metropolitan Museum of Art THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART Sept. 4 > Nov. 3, J 968 THE SMITH COLLEQE MUSEUM OF ART NORTHAMPTON, MASSACHUSETTS Nov. 20 - Dec. 29, 1968 THE UNIVERSITY OF KANSAS MUSEUM OF ART Jan. 10 - Feb. 3, 1969 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 68-6G722 S> THE UNIVERSITY OF KANSAS MUSEUM OF ART Miscellaneous Publications No. 74 o Jo I ACKNOWLEDQMENTS The present exhibition was organized by Mr. John Ittmann, a student in the Department of History of Art at the University of Kan sas. Mr. Ittmann's work in the Print Department of the Metropolitan Museum of Art during the summer of 19(38 was supported in part by an undergraduate research grant from the College of Arts and Sciences, The University of Kansas. All of the prints included in this exhibition with the few exceptions noted in the catalogue are from the collection of the Print Department of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. At the Metropolitan it has been possible to supplement the exhibition with additional prints, includ ing a small group of early color mezzotints, which are not listed in the present catalogue. We wish to thank the Trustees and Staff of The Metropolitan Museum of Art for approving the loan of these prints and The Smith College Museum of Art and Michael Wentworth for additional loans. Mr. Ittmann wishes to express his personal thanks to Mr. McKendry, Miss Janet Byrne and to all the members of the Print Department of the Metropolitan Museum of Art for their unfailing cooperation; to Miss Eleanor Sayre of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, for her en couragement and advice; and to Mrs. -

Engraving and Etching; a Handbook for The

CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY GIFT OF Geoffrey Steele FINE ARTS Cornell University Library NE 430.L76 1907 Engraving and etching; a handbook for the 3 1924 020 520 668 Cornell University Library The original of tiiis book is in tine Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924020520668 ENGRAVING AND ETCHING ENGRAVING AND ETCHING A HANDBOOK FOR THE USE OF STUDENTS AND PRINT COLLECTORS BY DR. FR. LIPPMANN LATE KEEPER OF THE PRINT ROOM IN THE ROYAL MUSEUM, BERLIN TRANSLATED FROM THE THIRD GERMAN EDITION REVISED BY DR. MAX LEHRS BY MARTIN HARDIE NATIONAL ART LIBRARY, VICTORIA AND ALBERT MUSEUM WITH 131 ILLUSTRATIONS ^ „ ' Us NEW YORK: CHARLES SCRIBNER'S SONS^;.,j^, 153—157 FIFTH AVENUE 1907 S|0 PRINTED BY HAZELL, WATSON AND VINEY, LD. LONDON AND AYLESBURY, ENGLAND. PREFACE TO THE FIRST EDITION '' I ^HE following history of the art of engraving closes -*• approximately with the beginning of the nine- teenth century. The more recent developments of the art have not been included, for the advent of steel- engraving, of lithography, and of modern mechanical processes has caused so wide a revolution in the repro- ductive arts that nineteenth-century engraving appears to require a separate history of its own and an entirely different treatment. The illustrations are all made to the exact size of the originals, though in some cases a detail only of the original is reproduced. PREFACE TO THE THIRD EDITION FRIEDRICH LIPPMANN died on October 2nd, to 1903, and it fell to me, as his successor in office, undertake a fresh revision of the handbook in preparation for a third edition. -

THE GLOBAL EYE Dutch, Spanish and Portuguese Maps in the Collections of the Grand Duke Cosimo III De’ Medici

Angelo Cattaneo Sabrina Corbellini THE GLOBAL EYE dutch, spanish and portuguese maps in the collections of the grand duke Cosimo III de’ Medici Mandragora Catalogue of the exhibition held at Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana, Florence from 7 November 2019 to 29 May 2020. ACCADEMIA DELLA CRUSCA Concept and Scientific Project Photographs © 2019 Mandragora. All rights reserved. Angelo Cattaneo and Sabrina Corbellini Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana*, Florence Mandragora s.r.l. via Capo di Mondo 61, 50136 Firenze Exhibition Layout Accademia della Crusca, Florence www.mandragora.it Fabrizio Monaci and Roberta Paganucci (photos by Alessio Misuri, Nicolò Orsi Battaglini) Alberto Bruschi, Grassina (Florence) © 2019 CHAM - Centre for the Humanities General Coordination Archivio di Stato di Firenze* NOVA School of Social Sciences and Humanities, Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana Deventer Collectie, Vereniging de Waag Universidade NOVA de Lisboa Direction: Anna Rita Fantoni Fototeca dei Musei Civici Fiorentini and University of Azores Exhibitions and Cultural Events Dept: Anna Rita Fundação da Casa de Bragança - Museu-Biblioteca, Av. de Berna, 26-C | 1069-061 Lisboa | Portugal Fantoni, Roberto Seriacopi Paço Ducal, Vila Viçosa (DGPC) [email protected] | www.cham.fcsh.unl.pt Reproductions Dept: Eugenia Antonucci Gallerie degli Uffizi*, Florence Manuscripts–Conservation Dept: Silvia Scipioni Kunsthandel Jacques Fijnaut, Amsterdam Administration: Carla Tanzi Monumentenfotografie, Rijksdienst voor het Editor Cultureel Erfgoed, afdeling Gebouwd Erfgoed Marco Salucci Multimedia Presentation Museo Galileo, Florence Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana: Eugenia Antonucci, Nationaal Archief, Den Haag English Translation Claudio Finocchi, Simone Falteri Nationaal Gevangenismuseum, Veenhuizen Sonia Hill, Ian Mansbridge Nederlands Scheepvaart Museum, Amsterdam Press Office Polo Museale della Toscana*, Florence Art director Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana: Silvia Scipioni Paola Vannucchi * By permission of the Ministero per i Beni e le Attività Culturali e per il Turismo.