Lamenting Patrick Og Maccrimmon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TT Skye Summer from 25Th May 2015.Indd

n Portree Fiscavaig Broadford Elgol Armadale Kyleakin Kyle Of Lochalsh Dunvegan Uig Flodigarry Staffi Includes School buses in Skye Skye 51 52 54 55 56 57A 57C 58 59 152 155 158 164 60X times bus Information correct at time of print of time at correct Information From 25 May 2015 May 25 From Armadale Broadford Kyle of Lochalsh 51 MONDAY TO FRIDAY (25 MAY 2015 UNTIL 25 OCTOBER 2015) SATURDAY (25 MAY 2015 UNTIL 25 OCTOBER 2015) NSch Service No. 51 51 51 51 51 51A 51 51 Service No. 51 51 51A 51 51 NSch NSch NSch School Armadale Pier - - - - - 1430 - - Armadale Pier - - 1430 - - Holidays Only Sabhal Mor Ostaig - - - - - 1438 - - Sabhal Mor Ostaig - - 1433 - - Isle Oronsay Road End - - - - - 1446 - - Isle Oronsay Road End - - 1441 - - Drumfearn Road End - - - - - 1451 - - Drumfearn Road End - - 1446 - - Broadford Hospital Road End 0815 0940 1045 1210 1343 1625 1750 Broadford Hospital Road End 0940 1343 1625 1750 Kyleakin Youth Hostel 0830 0955 1100 1225 1358 1509 1640 1805 Kyleakin Youth Hostel 0955 1358 1504 1640 1805 Kyle of Lochalsh Bus Terminal 0835 1000 1105 1230 1403 1514 1645 1810 Kyle of Lochalsh Bus Terminal 1000 1403 1509 1645 1810 NO SUNDAY SERVICE Kyle of Lochalsh Broadford Armadale 51 MONDAY TO FRIDAY (25 MAY 2015 UNTIL 25 OCTOBER 2015) SATURDAY (25 MAY 2015 UNTIL 25 OCTOBER 2015) NSch Service No. 51 51 51 51 51A 51 51 51 Service No. 51 51A 51 51 51 NSch NSch NSch NSch School Kyle of Lochalsh Bus Terminal 0740 0850 1015 1138 1338 1405 1600 1720 Kyle of Lochalsh Bus Terminal 0910 1341 1405 1600 1720 Holidays Only Kyleakin Youth -

The Misty Isle of Skye : Its Scenery, Its People, Its Story

THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA LOS ANGELES c.'^.cjy- U^';' D Cfi < 2 H O THE MISTY ISLE OF SKYE ITS SCENERY, ITS PEOPLE, ITS STORY BY J. A. MACCULLOCH EDINBURGH AND LONDON OLIPHANT ANDERSON & FERRIER 1905 Jerusalem, Athens, and Rome, I would see them before I die ! But I'd rather not see any one of the three, 'Plan be exiled for ever from Skye ! " Lovest thou mountains great, Peaks to the clouds that soar, Corrie and fell where eagles dwell, And cataracts dash evermore? Lovest thou green grassy glades. By the sunshine sweetly kist, Murmuring waves, and echoing caves? Then go to the Isle of Mist." Sheriff Nicolson. DA 15 To MACLEOD OF MACLEOD, C.M.G. Dear MacLeod, It is fitting that I should dedicate this book to you. You have been interested in its making and in its publica- tion, and how fiattering that is to an author s vanity / And what chief is there who is so beloved of his clansmen all over the world as you, or whose fiame is such a household word in dear old Skye as is yours ? A book about Skye should recognise these things, and so I inscribe your name on this page. Your Sincere Friend, THE A UTHOR. 8G54S7 EXILED FROM SKYE. The sun shines on the ocean, And the heavens are bhie and high, But the clouds hang- grey and lowering O'er the misty Isle of Skye. I hear the blue-bird singing, And the starling's mellow cry, But t4eve the peewit's screaming In the distant Isle of Skye. -

International Passenger Survey, 2008

UK Data Archive Study Number 5993 - International Passenger Survey, 2008 Airline code Airline name Code 2L 2L Helvetic Airways 26099 2M 2M Moldavian Airlines (Dump 31999 2R 2R Star Airlines (Dump) 07099 2T 2T Canada 3000 Airln (Dump) 80099 3D 3D Denim Air (Dump) 11099 3M 3M Gulf Stream Interntnal (Dump) 81099 3W 3W Euro Manx 01699 4L 4L Air Astana 31599 4P 4P Polonia 30699 4R 4R Hamburg International 08099 4U 4U German Wings 08011 5A 5A Air Atlanta 01099 5D 5D Vbird 11099 5E 5E Base Airlines (Dump) 11099 5G 5G Skyservice Airlines 80099 5P 5P SkyEurope Airlines Hungary 30599 5Q 5Q EuroCeltic Airways 01099 5R 5R Karthago Airlines 35499 5W 5W Astraeus 01062 6B 6B Britannia Airways 20099 6H 6H Israir (Airlines and Tourism ltd) 57099 6N 6N Trans Travel Airlines (Dump) 11099 6Q 6Q Slovak Airlines 30499 6U 6U Air Ukraine 32201 7B 7B Kras Air (Dump) 30999 7G 7G MK Airlines (Dump) 01099 7L 7L Sun d'Or International 57099 7W 7W Air Sask 80099 7Y 7Y EAE European Air Express 08099 8A 8A Atlas Blue 35299 8F 8F Fischer Air 30399 8L 8L Newair (Dump) 12099 8Q 8Q Onur Air (Dump) 16099 8U 8U Afriqiyah Airways 35199 9C 9C Gill Aviation (Dump) 01099 9G 9G Galaxy Airways (Dump) 22099 9L 9L Colgan Air (Dump) 81099 9P 9P Pelangi Air (Dump) 60599 9R 9R Phuket Airlines 66499 9S 9S Blue Panorama Airlines 10099 9U 9U Air Moldova (Dump) 31999 9W 9W Jet Airways (Dump) 61099 9Y 9Y Air Kazakstan (Dump) 31599 A3 A3 Aegean Airlines 22099 A7 A7 Air Plus Comet 25099 AA AA American Airlines 81028 AAA1 AAA Ansett Air Australia (Dump) 50099 AAA2 AAA Ansett New Zealand (Dump) -

Trek the Skye Trail

Trek the Skye Trail Europe | 900m www.360-expeditions.com Trek the Skye Trail Europe | 900m Join us on this 9-day expedition trekking the clearances and visit remote island Skye Trail, an established but less trodden communities and also have superb and, for the most part, deserted route opportunities for watching wildlife and if covering 27km (79 miles) from the North to the we’re lucky we may catch sight of seals, South of the island of Skye. There are no otters, golden eagles and sea eagles! waymarks on the route and many sections do not even have a path, however, we know this This route is perfect for those who want to get route well and the rewards as you walk south well away from the beaten track and is a trek from the most northerly point on the island never to be forgotten! are spectacular. Whilst on our trek we will be treated to some of the finest mountain views in the UK, passing under the shadows of the jagged Red and Black Cuillins (possibly the finest mountain range in Britain). We’ll also be taking in the breath-taking coastal scenery from beaches to cliff-tops in areas that are remarkable but almost unvisited. We’ll encounter haunting ruins of villages deserted during the highland [email protected] CLICK TO: 0207 1834 360 www.360-expeditions.com BOOK NOW Trek the Skye Trail Europe | 900m Physical - P2 Technical - T1 Prolonged walking over varied terrain. There No technical skills are needed. A good steady may be uphills and downhills, so a good solid walking ability only is required. -

Macleod of Macleod's Lament

MacLeod of MacLeod's Lament There are settings of this tune in the following manuscript: --Robert Meldrum's MS, ff.221-223 (with the title "Lament for Sir Rory Mor MacLeod of MacLeod") And in the following published sources: --Angus MacKay's Ancient Piobaireachd, pp.131-4 --Donald MacPhee's Collection of Piobaireachd, ii, 11-14 --C. S. Thomason's Ceol Mor, pp.165-6 --David Glen's Ancient Piobaireachd, pp.51-3 --William Stewart, Piobaireachd Society Collection (first series), ii, 1-4 --G. F. Ross, MacCrimmon and Other Piobaireachd, pp.26-7 The earliest source is Angus MacKay's published book. The tune is a four lined even one, with eight bars in each of the parts, as the second variation doubling implies. In MacKay's setting the end of the first line is an eallach short: "A thread of pride and self esteem…" © Dr. William Donaldson Published by Piper & Drummer Online, 2004-'05 "A thread of pride and self esteem…" © Dr. William Donaldson Published by Piper & Drummer Online, 2004-'05 And so on. Donald MacPhee made good this obvious slip in the second volume of his published collection, and most later editors followed MacPhee: "A thread of pride and self esteem…" © Dr. William Donaldson Published by Piper & Drummer Online, 2004-'05 "A thread of pride and self esteem…" © Dr. William Donaldson Published by Piper & Drummer Online, 2004-'05 "A thread of pride and self esteem…" © Dr. William Donaldson Published by Piper & Drummer Online, 2004-'05 "A thread of pride and self esteem…" © Dr. William Donaldson Published by Piper & Drummer Online, 2004-'05 "A thread of pride and self esteem…" © Dr. -

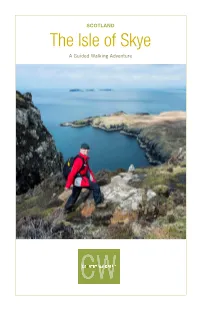

Scotland-The-Isle-Of-Skye-2016.Pdf

SCOTLAND The Isle of Skye A Guided Walking Adventure Table of Contents Daily Itinerary ........................................................................... 4 Tour Itinerary Overview .......................................................... 13 Tour Facts at a Glance ........................................................... 15 Traveling To and From Your Tour .......................................... 17 Information & Policies ............................................................ 20 Scotland at a Glance .............................................................. 22 Packing List ........................................................................... 26 800.464.9255 / countrywalkers.com 2 © 2015 Otago, LLC dba Country Walkers Travel Style This small-group Guided Walking Adventure offers an authentic travel experience, one that takes you away from the crowds and deep in to the fabric of local life. On it, you’ll enjoy 24/7 expert guides, premium accommodations, delicious meals, effortless transportation, and local wine or beer with dinner. Rest assured that every trip detail has been anticipated so you’re free to enjoy an adventure that exceeds your expectations. And, with our new optional Flight + Tour Combo and PrePrePre-Pre ---TourTour Edinburgh Extension to complement this destination, we take care of all the travel to simplify the journey. Refer to the attached itinerary for more details. Overview Unparalleled scenery, incredible walks, local folklore, and history come together effortlessly in the Highlands and -

Watsonia 17 (1989), 463-486

Watsonia, 17, 463-486 (1989) 463 Plant Records Records for publication must be submitted to the appropriate Vice-county Recorder (see Vice-county Recorders (1988)), and not the Editors. The records must normally be of species, hybrids or subspecies of native or naturalized alien plants belonging to one or more of the following categories: 1st or 2nd v.c. record; 1st post-1930 v.c. record; only extant v.c.locality, or 2nd such locality; a record of an extension of range by more than 100 km. Such records will also be accepted for the major islands in V.cc. 102-104 and 110. Only 1st records can be accepted for Rubus, Hieracium and hybrids. Records for subdivisions of vice-counties will not be treated separately; they must therefore be records for the vice-county as a whole. Records of Taraxacum are now being dealt with separately, by Dr A. J. Richards, and will be published at a later date. Records are arranged in the order given in the List of British vascular plants by J. E. Dandy (1958) and his subsequent revision (Watsonia, 7: 157-178 (1969)). All records are field records unless otherwise stated. With the exception of collectors' initials, herbarium abbreviations are those used in British and Irish herbaria by D. H. Kent & D. E . Alien (1984). Records from the following vice-counties are included in the text below: 2,4-7,11-14,17,25-27,33-35,38- 51,59-62,64,65,67-73,75,77-81,83,88,93,96,98,99, 101, 103, 104, 111, H5, H8, H21, H33, H39. -

The Piobaireachd Society of Central Pennsylvania What Is Piobaireachd? There Were Several Hereditary Lines of Pipers Throughout the Highlands

Volume 5, Issue 2 March 2018 The Piobaireachd Society of Central Pennsylvania What is Piobaireachd? There were several hereditary lines of pipers throughout the highlands. The “Piobaireachd” literally means “pipe most important line comes through the playing” or “pipe music.” However, in MacCrimmons of Skye. The recent times it has come to represent the MacCrimmons were hereditary pipers to type of music known as Ceol Mor. The the MacLeods on the Isle of Skye. The music for the Highland Bagpipe can be MacCrimmons were given lands near divided into three classes of music: Ceol Dunvegan Castle, known as Boreraig. Beag, Ceol Meadhonach, and Ceol Mor. The MacCrimmon cairn (stone Ceol Beag (Little Music) is the gaelic monument) was recently erected to mark name for the classification of tunes the place where the MacCrimmons held known as Marches, strathspeys & reels. their famous piping school at Boreraig. Marches came out of the military tradition On the solo competition circuit, of the 19th century. Strathspeys & Reels piobaireachd is where it’s at. The came out of the dance traditions. Highland Society gold medals at the Ceol Meadhonach (Middle Music) refers Argyllshire Gathering in Oban and the to the jigs, hornpipes and slow airs. Slow Northern Meeting in Inverness are airs were played by the ancient piping considered the pinnacle achievements by masters, however, jigs and hornpipes are many pipers. fairly modern additions to a piper’s Piobaireachd truly is Ceol Mor, the repertoire. “Great Music” of the Highland bagpipe. Ceol Mor (Great Music) is the classical music for the Highland Bagpipe, also known as, piobaireachd. -

History of the Macleods with Genealogies of the Principal

*? 1 /mIB4» » ' Q oc i. &;::$ 23 j • or v HISTORY OF THE MACLEODS. INVERNESS: PRINTED AT THE "SCOTTISH HIGHLANDER" OFFICE. HISTORY TP MACLEODS WITH GENEALOGIES OF THE PRINCIPAL FAMILIES OF THE NAME. ALEXANDER MACKENZIE, F.S.A. Scot., AUTHOR OF "THE HISTORY AND GENEALOGIES OF THE CLAN MACKENZIE"; "THE HISTORY OF THE MACDONALDS AND LORDS OF THE ISLES;" "THE HISTORY OF THE CAMERON'S;" "THE HISTORY OF THE MATHESONS ; " "THE " PROPHECIES OF THE BRAHAN SEER ; " THE HISTORICAL TALES AND LEGENDS OF THE HIGHLANDS;" "THE HISTORY " OF THE HIGHLAND CLEARANCES;" " THE SOCIAL STATE OF THE ISLE OF SKYE IN 1882-83;" ETC., ETC. MURUS AHENEUS. INVERNESS: A. & W. MACKENZIE. MDCCCLXXXIX. J iBRARY J TO LACHLAN MACDONALD, ESQUIRE OF SKAEBOST, THE BEST LANDLORD IN THE HIGHLANDS. THIS HISTORY OF HIS MOTHER'S CLAN (Ann Macleod of Gesto) IS INSCRIBED BY THE AUTHOR. Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2012 with funding from National Library of Scotland http://archive.org/details/historyofmacleodOOmack PREFACE. -:o:- This volume completes my fifth Clan History, written and published during the last ten years, making altogether some two thousand two hundred and fifty pages of a class of literary work which, in every line, requires the most scrupulous and careful verification. This is in addition to about the same number, dealing with the traditions^ superstitions, general history, and social condition of the Highlands, and mostly prepared after business hours in the course of an active private and public life, including my editorial labours in connection with the Celtic Maga- zine and the Scottish Highlander. This is far more than has ever been written by any author born north of the Grampians and whatever may be said ; about the quality of these productions, two agreeable facts may be stated regarding them. -

The Isle of Skye in 1882-1883

THE OF SK ALEXANDER MACKENZIE F.S.A. SCO'! THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA LOS ANGELES THE ISLE OF SKYE IN i882-i883; ILLUSTRATED BY A FULL REPORT OF THE TRIALS OF THE BRAES AND GLENDALE CROFTERS, AT INVERNESS AND EDINBURGH ; AND AN 'INTRODUCTORY CHAPTER. ALEXANDER MACKENZIE, F.S.A., SCOT., EDITOR OF THE Celtic Magazine ; AUTHOR OF The History of the Highland Clearances; T/ie History of the Mackenzies; The History of the Macdonalds and Lords of the Isles ; The Macdonalds of Glengarry ; The Macdonalds ofClanranald ; The History of the Mathesons ; The Prophecies of the Brahan Seer; The Historical Tales and Legends of the High- lands, &"c. ALSO A FULL REPORT OF THE TRIAL OF PATRICK SELLAR. INVERNESS: A. & W. MACKENZIE. 1883. ABERDEEN UNIVERSITY PRESS. A * MR. KENNETH MACDONALD, F.S.A, SCOT., TOWN-CLERK OF INVERNESS, A GENUINE FRIEND, AND AN ABLE ADVOCATE OF THE RIGHTS OF THE HIGHLAND PEOPLE, BY HIS FRIEND, THE AUTHOR. 879203 CONTENTS. Introduction : General Remarks ix Sleat and Strath xvii Bracadale xx Glendale xxvii Dr. Martin's Estate xxix Dunvegan xxix Waternish xxxi Grishornish and Lyndale xxxii Kilmuir Major Eraser's xxxiii The Brave Old Crofter xxxvii Eviction Results in Skye xlii Rent' of Benlee paid by Malcolm Mackenzie xliii Liberation of the Glendale Martyrs xliv The Scotsman in the Scales xlvi Patrick Sellar's Trial Hi Lord Napier as Chairman of the Royal Commission liv The Social Revolution in the Braes ; The Braes Crofters and Lord Macdonald 7 The Glendale Crofters and their Grievances 13 Dr. Nicol Martin's Estate Management 22 Burning of the First Summonses in the Braes 24 March of the Dismal Brigade, and Battle of the Braes. -

A'chleit (Argyll), A' Chleit

Iain Mac an Tàilleir 2003 1 A'Chleit (Argyll), A' Chleit. "The mouth of the Lednock", an obscure "The cliff or rock", from Norse. name. Abban (Inverness), An t-Àban. Aberlemno (Angus), Obar Leamhnach. “The backwater” or “small stream”. "The mouth of the elm stream". Abbey St Bathans (Berwick). Aberlour (Banff), Obar Lobhair. "The abbey of Baoithean". The surname "The mouth of the noisy or talkative stream". MacGylboythin, "son of the devotee of Aberlour Church and parish respectively are Baoithean", appeared in Dumfries in the 13th Cill Drostain and Sgìre Dhrostain, "the century, but has since died out. church and parish of Drostan". Abbotsinch (Renfrew). Abernethy (Inverness, Perth), Obar Neithich. "The abbot's meadow", from English/Gaelic, "The mouth of the Nethy", a river name on lands once belonging to Paisley Abbey. suggesting cleanliness. Aberarder (Inverness), Obar Àrdair. Aberscross (Sutherland), Abarsgaig. "The mouth of the Arder", from àrd and "Muddy strip of land". dobhar. Abersky (Inverness), Abairsgigh. Aberargie (Perth), Obar Fhargaidh. "Muddy place". "The mouth of the angry river", from fearg. Abertarff (Inverness), Obar Thairbh. Aberbothrie (Perth). "The mouth of the bull river". Rivers and "The mouth of the deaf stream", from bodhar, stream were often named after animals. “deaf”, suggesting a silent stream. Aberuchill (Perth), Obar Rùchaill. Abercairney (Perth). Although local Gaelic speakers understood "The mouth of the Cairney", a river name this name to mean "mouth of the red flood", from càrnach, meaning “stony”. from Obar Ruadh Thuil, older evidence Aberchalder (Inverness), Obar Chaladair. points to this name containing coille, "The mouth of the hard water", from caled "wood", with similarities to Orchill. -

Scottish Clans & Castles

Scottish Clans & Castles Starting at $2449.00* Find your castle in the sky Trip details Revisit the past on this leisurely Scottish tour filled with Tour start Tour end Trip Highlights: castle ruins, ancient battlefields, and colorful stories Glasgow Edinburgh • Dunvegan Castle from the country's rich history. • Palace of Holyroodhouse 10 9 15 • Isle of Skye Days Nights Meals • Culloden Battlefield • Eilean Donan Castle • Stirling Castle • Doune Castle Hotels: • Malmaison Glasgow • Balmacara Hotel • Glen Mhor Hotel • Norton House Hotel & Spa 2020 Scottish Clans & Castles 10 day/9 night tour Trip Itinerary Day 2 Stirling Castle | Doune Castle | Distillery Visit Day 1 Glasgow Arrival | City Tour Visit Stirling Castle, a mighty stronghold that dominates the surrounding plain, Tour begins at 2:00 PM at your hotel. Enjoy a Glasgow city tour to see George before some free time on your own for lunch. Visit the 14th century Doune Castle, Square, Glasgow Cathedral, Kelvingrove Park, and Glasgow University, all featured with its 100-foot-high gatehouse and well-preserved great hall. The formidable in the TV series Outlander. Enjoy a welcome drink with your group before dining structure has been used as a film location for many productions, including Monty independently. Python and the Holy Grail. Next, head to a whisky distillery for a sampling, then go back to Glasgow to dine at your hotel. (B, D) Day 3 Glencoe | Eilean Donan Castle Day 4 Isle of Skye | Dunvegan Castle | Kilt Rock | Portree Head into the majestic Highlands and journey by Loch Lomond, across Rannoch Explore the Isle of Skye and learn the history of Bonnie Prince Charlie.