A Summer in Skye

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2020 Cruise Directory Directory 2020 Cruise 2020 Cruise Directory M 18 C B Y 80 −−−−−−−−−−−−−−− 17 −−−−−−−−−−−−−−−

2020 MAIN Cover Artwork.qxp_Layout 1 07/03/2019 16:16 Page 1 2020 Hebridean Princess Cruise Calendar SPRING page CONTENTS March 2nd A Taste of the Lower Clyde 4 nights 22 European River Cruises on board MS Royal Crown 6th Firth of Clyde Explorer 4 nights 24 10th Historic Houses and Castles of the Clyde 7 nights 26 The Hebridean difference 3 Private charters 17 17th Inlets and Islands of Argyll 7 nights 28 24th Highland and Island Discovery 7 nights 30 Genuinely fully-inclusive cruising 4-5 Belmond Royal Scotsman 17 31st Flavours of the Hebrides 7 nights 32 Discovering more with Scottish islands A-Z 18-21 Hebridean’s exceptional crew 6-7 April 7th Easter Explorer 7 nights 34 Cruise itineraries 22-97 Life on board 8-9 14th Springtime Surprise 7 nights 36 Cabins 98-107 21st Idyllic Outer Isles 7 nights 38 Dining and cuisine 10-11 28th Footloose through the Inner Sound 7 nights 40 Smooth start to your cruise 108-109 2020 Cruise DireCTOrY Going ashore 12-13 On board A-Z 111 May 5th Glorious Gardens of the West Coast 7 nights 42 Themed cruises 14 12th Western Isles Panorama 7 nights 44 Highlands and islands of scotland What you need to know 112 Enriching guest speakers 15 19th St Kilda and the Outer Isles 7 nights 46 Orkney, Northern ireland, isle of Man and Norway Cabin facilities 113 26th Western Isles Wildlife 7 nights 48 Knowledgeable guides 15 Deck plans 114 SuMMER Partnerships 16 June 2nd St Kilda & Scotland’s Remote Archipelagos 7 nights 50 9th Heart of the Hebrides 7 nights 52 16th Footloose to the Outer Isles 7 nights 54 HEBRIDEAN -

Walks and Scrambles in the Highlands

Frontispiece} [Photo by Miss Omtes, SLIGACHAN BRIDGE, SGURR NAN GILLEAN AND THE BHASTEIR GROUP. WALKS AND SCRAMBLES IN THE HIGHLANDS. BY ARTHUR L. BAGLEY. WITH TWELVE ILLUSTRATIONS. Xon&on SKEFFINGTON & SON 34 SOUTHAMPTON STREET, STRAND, W.C. PUBLISHERS TO HIS MAJESTY THE KING I9H Richard Clav & Sons, Limiteu, brunswick street, stamford street s.e., and bungay, suffolk UNiVERi. CONTENTS BEN CRUACHAN ..... II CAIRNGORM AND BEN MUICH DHUI 9 III BRAERIACH AND CAIRN TOUL 18 IV THE LARIG GHRU 26 V A HIGHLAND SUNSET .... 33 VI SLIOCH 39 VII BEN EAY 47 VIII LIATHACH ; AN ABORTIVE ATTEMPT 56 IX GLEN TULACHA 64 X SGURR NAN GILLEAN, BY THE PINNACLES 7i XI BRUACH NA FRITHE .... 79 XII THROUGH GLEN AFFRIC 83 XIII FROM GLEN SHIEL TO BROADFORD, BY KYLE RHEA 92 XIV BEINN NA CAILLEACH . 99 XV FROM BROADFORD TO SOAY . 106 v vi CONTENTS CHAF. PACE XVI GARSBHEINN AND SGURR NAN EAG, FROM SOAY II4 XVII THE BHASTEIR . .122 XVIII CLACH GLAS AND BLAVEN . 1 29 XIX FROM ELGOL TO GLEN BRITTLE OVER THE DUBHS 138 XX SGURR SGUMA1N, SGURR ALASDAIR, SGURR TEARLACH AND SGURR MHIC CHOINNICH . I47 XXI FROM THURSO TO DURNESS . -153 XXII FROM DURNESS TO INCHNADAMPH . 1 66 XXIII BEN MORE OF ASSYNT 1 74 XXIV SUILVEN 180 XXV SGURR DEARG AND SGURR NA BANACHDICH . 1 88 XXVI THE CIOCH 1 96 1 LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Toface page SLIGACHAN BRIDGE, SGURR NAN GILLEAN AND THE bhasteir group . Frontispiece BEN CRUACHAN, FROM NEAR DALMALLY . 4 LOCH AN EILEAN ....... 9 AMONG THE CAIRNGORMS ; THE LARIG GHRU IN THE DISTANCE . -31 VIEW OF SKYE, FROM NEAR KYLE OF LOCH ALSH . -

Ullinish Country Lodge Struan, Isle of Skye, IV56

Offers Over Ullinish Country Lodge £599,000 (Freehold) Struan, Isle Of Skye, IV56 8FD An outstanding example of a substantial and excellently presented hospitality business with dramatic views of the Black Cuillin and MacLeod’s Tables Currently trading as a bed and breakfast but previously operated as a restaurant with rooms Set within stunning landscapes with sea views on the ever-popular Isle of Skye Uncomplicated and profitable “home and income” lifestyle business opportunity with potential for further business development Six characterful and lavish en-suite letting bedrooms as well as opulent public rooms including beautifully authentic and well- presented restaurant to seat c20 diners Spacious owner’s accommodation / staff rooms (4 bedrooms with 1 en-suite and private lounge) plus excellent service areas Included is a range of out buildings all set within 6 acres; offering some development potential subject to planning consents DESCRIPTION Ullinish Country Lodge is a most attractive property in a destination location, enjoying an elevated position with stunning views towards the mountains and sea. The property has a well recorded 300-year history which is evident throughout. This prominent business has a significant footprint within 6 acres. Located on the Isle of Skye, this is truly a must view property for anyone wishing to own a prestigious business with superlative views. The vendor has significantly upgraded and improved the property during their tenure, now presenting a truly walk-in business opportunity. The owner takes great pride in presenting their charming property to guests, ensuring they receive a particularly warm and friendly welcome. The reception area is spacious and leads to the sumptuous guest lounge which is set to sofas with an open fire and double aspect views. -

Sleat Community Hydro Neart an Uillt

SLEAT COMMUNITY HYDRO NEART AN UILLT SHARE PROSPECTUS share offer target: £235,000 Summary of Minimum investment: £250 the Proposal maximum investment: £25,000 Cumhachd Shlèite is a proposed 34 kW run-of-river micro hydro development in the community-owned Tormore Forest. Sleat Hydro Community Benefit Society Launch date: 7 December 2020 are responsible for managing the project and have produced this document to detail the opportunity to End date: 28 february 2021 invest in the society through a community share offer. This project will deliver clean, renewable energy to contribute to fighting the climate emergency and reducing our carbon footprint. Cumhachd Shlèite will also benefit our community as all profits from the scheme will be used to fund sustainable local projects. Investors will receive modest interest payments on their investment as well as the opportunity to become a member of the society and contribute to the organisation of the scheme. clean Allt a’ Cham-aird renewable energy This latest development is the next step in creating a Sustainable Sleat. Sleat is the southernmost peninsula of the community are members Community Shares Standard Mark. A subscription for shares in Sleat Hydro Community of the Isle of Skye with a population and recent initiatives include the Benefit Society should be regarded as both an This share offer has been awarded the Community overview of approximately 900 people. It has community broadband service investment for social and environmental purposes and Shares Standard Mark, awarded by the Community a rich and turbulent history and now Skyenet; providing split logs to one that could produce a modest financial return. -

Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination

Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination Anglophone Writing from 1600 to 1900 Silke Stroh northwestern university press evanston, illinois Northwestern University Press www .nupress.northwestern .edu Copyright © 2017 by Northwestern University Press. Published 2017. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data are available from the Library of Congress. Except where otherwise noted, this book is licensed under a Creative Commons At- tribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. In all cases attribution should include the following information: Stroh, Silke. Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination: Anglophone Writing from 1600 to 1900. Evanston, Ill.: Northwestern University Press, 2017. For permissions beyond the scope of this license, visit www.nupress.northwestern.edu An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high-quality books open access for the public good. More information about the initiative and links to the open-access version can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org Contents Acknowledgments vii Introduction 3 Chapter 1 The Modern Nation- State and Its Others: Civilizing Missions at Home and Abroad, ca. 1600 to 1800 33 Chapter 2 Anglophone Literature of Civilization and the Hybridized Gaelic Subject: Martin Martin’s Travel Writings 77 Chapter 3 The Reemergence of the Primitive Other? Noble Savagery and the Romantic Age 113 Chapter 4 From Flirtations with Romantic Otherness to a More Integrated National Synthesis: “Gentleman Savages” in Walter Scott’s Novel Waverley 141 Chapter 5 Of Celts and Teutons: Racial Biology and Anti- Gaelic Discourse, ca. -

South Skye Web.Indd

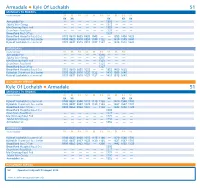

Armadale G Kyle Of Lochalsh 51 MONDAYS TO FRIDAYS route number 51 51 51 51 51 51 51 51 51 51 XX XX XX XX XX Armadale Pier — — — — — — 1310 — — — Sabhal Mor Ostaig — — — — — — 1315 — — — Isle Oronsay Road End — — — — — — 1323 — — — Drumfearn Road End — — — — — — 1328 — — — Broadford Post Offi ce — — — — — — 1337 — — — Broadford Hospital Road End 0715 0810 0855 0935 1045 — — 1355 1450 1625 Kyleakin Shorefront bus shelter 0730 0825 0910 0950 1100 1122 — 1410 1505 1640 Kyle of Lochalsh bus terminal 0737 0831 0915 0957 1107 1127 — 1415 1512 1647 SATURDAYS route number 51 51 51 51 51 51 51 51 51 Armadale Pier — — — — — 1310 — — — Sabhal Mor Ostaig — — — — — 1315 — — — Isle Oronsay Road End — — — — — 1323 — — — Drumfearn Road End — — — — — 1328 — — — Broadford Post Offi ce — — — — — 1337 — — — Broadford Hospital Road End 0715 0810 0855 1005 — — 1355 1450 1625 Kyleakin Shorefront bus shelter 0730 0825 0910 1020 1122 — 1410 1505 1640 Kyle of Lochalsh bus terminal 0737 0831 0915 1027 1127 — 1415 1512 1647 NO SUNDAY SERVICE Kyle Of Lochalsh G Armadale 51 MONDAYS TO FRIDAYS route number 51 51 51 51 51 51 51 51 51 51 XX XX XX XX XX Kyle of Lochalsh bus terminal 0740 0832 0900 1015 1115 1138 — 1420 1540 1700 Kyleakin Shorefront bus shelter 0745 0837 0907 1022 1120 1143 — 1427 1547 1707 Broadford Post Offi ce 0800 0852 0922 1037 — 1158 — 1442 1602 1722 Broadford Hospital Road End — — — — — — 1205 — — — Drumfearn Road End — — — — — — 1217 — — — Isle Oronsay Road End — — — — — — 1222 — — — Sabhal Mor Ostaig — — — — — — 1230 — — — Armadale Pier — — — — — — -

Former Fellows Biographical Index Part

Former Fellows of The Royal Society of Edinburgh 1783 – 2002 Biographical Index Part Two ISBN 0 902198 84 X Published July 2006 © The Royal Society of Edinburgh 22-26 George Street, Edinburgh, EH2 2PQ BIOGRAPHICAL INDEX OF FORMER FELLOWS OF THE ROYAL SOCIETY OF EDINBURGH 1783 – 2002 PART II K-Z C D Waterston and A Macmillan Shearer This is a print-out of the biographical index of over 4000 former Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh as held on the Society’s computer system in October 2005. It lists former Fellows from the foundation of the Society in 1783 to October 2002. Most are deceased Fellows up to and including the list given in the RSE Directory 2003 (Session 2002-3) but some former Fellows who left the Society by resignation or were removed from the roll are still living. HISTORY OF THE PROJECT Information on the Fellowship has been kept by the Society in many ways – unpublished sources include Council and Committee Minutes, Card Indices, and correspondence; published sources such as Transactions, Proceedings, Year Books, Billets, Candidates Lists, etc. All have been examined by the compilers, who have found the Minutes, particularly Committee Minutes, to be of variable quality, and it is to be regretted that the Society’s holdings of published billets and candidates lists are incomplete. The late Professor Neil Campbell prepared from these sources a loose-leaf list of some 1500 Ordinary Fellows elected during the Society’s first hundred years. He listed name and forenames, title where applicable and national honours, profession or discipline, position held, some information on membership of the other societies, dates of birth, election to the Society and death or resignation from the Society and reference to a printed biography. -

Offers Over £65000 Plot at 23 Tarskavaig

The Isle of Skye Estate Agency Portree Office: [email protected] The Isle of Skye Estate Agency 01478 612 683 Kyle Office: [email protected] www.iosea.co.uk 01599 534 555 Plot at 23 Tarskavaig Offers Over £65,000 0.25 Acres (to be confirmed with title). Planning in Principle Panoramic Views Excellent Location Planning Ref : 17/05692/PIP Elevated Description: Excellent opportunity to purchase an area of land located in the township of Tarskavaig on the popular Sleat penin- sular. The site benefits from planning permission in princi- ple for the erection of a single or 1 ½ storey property. The road to Tarskcavaig is very picturesque and really lives up to the name given to Sleat – ‘The garden of Skye’ with the luscious greenery and woodland settings. The whole site extends to 0.25 acre or thereby (to be con- firmed with title) and offers widespread views across Loch a’Ghlinne and over to the small isles and beyond. The plot is well positioned to take advantage of the stunning views afforded by the area. Sites in this area do not be- come available very often and this is a rare opportunity to acquire a plot that is ideally positioned to take advantage of the amenities that this beautiful area has to offer. Planning Permission in Principle has been granted for the erection of a single or 1 ½ storey property, dated Mon 05 Mar 2018 . Full details are available on request. All docu- ments can be viewed on the Highland Council Website www.highland.gov.uk, using the planning reference num- ber 17/05692/PIP which is the allocated renewal num- ber. -

TT Skye Summer from 25Th May 2015.Indd

n Portree Fiscavaig Broadford Elgol Armadale Kyleakin Kyle Of Lochalsh Dunvegan Uig Flodigarry Staffi Includes School buses in Skye Skye 51 52 54 55 56 57A 57C 58 59 152 155 158 164 60X times bus Information correct at time of print of time at correct Information From 25 May 2015 May 25 From Armadale Broadford Kyle of Lochalsh 51 MONDAY TO FRIDAY (25 MAY 2015 UNTIL 25 OCTOBER 2015) SATURDAY (25 MAY 2015 UNTIL 25 OCTOBER 2015) NSch Service No. 51 51 51 51 51 51A 51 51 Service No. 51 51 51A 51 51 NSch NSch NSch School Armadale Pier - - - - - 1430 - - Armadale Pier - - 1430 - - Holidays Only Sabhal Mor Ostaig - - - - - 1438 - - Sabhal Mor Ostaig - - 1433 - - Isle Oronsay Road End - - - - - 1446 - - Isle Oronsay Road End - - 1441 - - Drumfearn Road End - - - - - 1451 - - Drumfearn Road End - - 1446 - - Broadford Hospital Road End 0815 0940 1045 1210 1343 1625 1750 Broadford Hospital Road End 0940 1343 1625 1750 Kyleakin Youth Hostel 0830 0955 1100 1225 1358 1509 1640 1805 Kyleakin Youth Hostel 0955 1358 1504 1640 1805 Kyle of Lochalsh Bus Terminal 0835 1000 1105 1230 1403 1514 1645 1810 Kyle of Lochalsh Bus Terminal 1000 1403 1509 1645 1810 NO SUNDAY SERVICE Kyle of Lochalsh Broadford Armadale 51 MONDAY TO FRIDAY (25 MAY 2015 UNTIL 25 OCTOBER 2015) SATURDAY (25 MAY 2015 UNTIL 25 OCTOBER 2015) NSch Service No. 51 51 51 51 51A 51 51 51 Service No. 51 51A 51 51 51 NSch NSch NSch NSch School Kyle of Lochalsh Bus Terminal 0740 0850 1015 1138 1338 1405 1600 1720 Kyle of Lochalsh Bus Terminal 0910 1341 1405 1600 1720 Holidays Only Kyleakin Youth -

The Misty Isle of Skye : Its Scenery, Its People, Its Story

THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA LOS ANGELES c.'^.cjy- U^';' D Cfi < 2 H O THE MISTY ISLE OF SKYE ITS SCENERY, ITS PEOPLE, ITS STORY BY J. A. MACCULLOCH EDINBURGH AND LONDON OLIPHANT ANDERSON & FERRIER 1905 Jerusalem, Athens, and Rome, I would see them before I die ! But I'd rather not see any one of the three, 'Plan be exiled for ever from Skye ! " Lovest thou mountains great, Peaks to the clouds that soar, Corrie and fell where eagles dwell, And cataracts dash evermore? Lovest thou green grassy glades. By the sunshine sweetly kist, Murmuring waves, and echoing caves? Then go to the Isle of Mist." Sheriff Nicolson. DA 15 To MACLEOD OF MACLEOD, C.M.G. Dear MacLeod, It is fitting that I should dedicate this book to you. You have been interested in its making and in its publica- tion, and how fiattering that is to an author s vanity / And what chief is there who is so beloved of his clansmen all over the world as you, or whose fiame is such a household word in dear old Skye as is yours ? A book about Skye should recognise these things, and so I inscribe your name on this page. Your Sincere Friend, THE A UTHOR. 8G54S7 EXILED FROM SKYE. The sun shines on the ocean, And the heavens are bhie and high, But the clouds hang- grey and lowering O'er the misty Isle of Skye. I hear the blue-bird singing, And the starling's mellow cry, But t4eve the peewit's screaming In the distant Isle of Skye. -

Trek the Skye Trail

Trek the Skye Trail Europe | 900m www.360-expeditions.com Trek the Skye Trail Europe | 900m Join us on this 9-day expedition trekking the clearances and visit remote island Skye Trail, an established but less trodden communities and also have superb and, for the most part, deserted route opportunities for watching wildlife and if covering 27km (79 miles) from the North to the we’re lucky we may catch sight of seals, South of the island of Skye. There are no otters, golden eagles and sea eagles! waymarks on the route and many sections do not even have a path, however, we know this This route is perfect for those who want to get route well and the rewards as you walk south well away from the beaten track and is a trek from the most northerly point on the island never to be forgotten! are spectacular. Whilst on our trek we will be treated to some of the finest mountain views in the UK, passing under the shadows of the jagged Red and Black Cuillins (possibly the finest mountain range in Britain). We’ll also be taking in the breath-taking coastal scenery from beaches to cliff-tops in areas that are remarkable but almost unvisited. We’ll encounter haunting ruins of villages deserted during the highland [email protected] CLICK TO: 0207 1834 360 www.360-expeditions.com BOOK NOW Trek the Skye Trail Europe | 900m Physical - P2 Technical - T1 Prolonged walking over varied terrain. There No technical skills are needed. A good steady may be uphills and downhills, so a good solid walking ability only is required. -

Portland Daily Press: June 01,1866

Maine State Library Digital Maine Portland Daily Press, 1866 Portland Daily Press 6-1-1866 Portland Daily Press: June 01,1866 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalmaine.com/pdp_1866 Recommended Citation "Portland Daily Press: June 01,1866" (1866). Portland Daily Press, 1866. 127. https://digitalmaine.com/pdp_1866/127 This Text is brought to you for free and open access by the Portland Daily Press at Digital Maine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Portland Daily Press, 1866 by an authorized administrator of Digital Maine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. * * DAILY PRESS. I'Htnb1 {fthiCtl June 1862. Vo/. A. 23, PORTLAND, FRIDAY MORNING, JUNE 1,1866. Terms $8 p.er annum, in advance. THE PORTLAND DAILY PRESS is published PORTLAND AND VICINITY. Tribute of Respect. had •vary excepted,)at 82 Exchange Street, New New Advertisements. THE FENIANS. ng you for so many years at the head of day, (Sunday Advertisements. A of the members of tbe Board of Trade I Portland, N. A. Fohteu, Proprietor. »If meeting lier maritime and admiralty court TELEGRAPH, Nevr Advertisement! To-Day and of the Merchants* was called at half I Thumb :—Eight Dollar? a year in advance. Exchange Tlie people who have sulnlucd and controll- TO A Modern Miratle. action as e. SHERIFF'S SALE. THE DAILY PRESS. past eleven o’clock yesterdays to bike such the sea have from (lie the Rations Preserve your Health. earliest times dictat- THE MAfNE STATE PRESS, if published Proposals for would seem to bo the most expression ot a Bodies North- Lime.