The Onomastics of Prinicipal Anlo-Town Names.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Field Test of New Features & Adaptations Based on On- Going Feedback

FIELD TEST OF NEW FEATURES & ADAPTATIONS BASED ON ON- GOING FEEDBACK USAID/GHANA JUSTICE SECTOR REFORM CASE TRACKING SYSTEM ACTIVITY October 29, 2019 This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by Chemonics International Inc. FIELD TEST OF NEW FEATURES & ADAPTATIONS BASED ON ON- GOING FEEDBACK USAID/GHANA JUSTICE SECTOR REFORM CASE TRACKING SYSTEM ACTIVITY Contract No. AID-OOA-I-13-00032, Task Order No. 72064118F00001 Cover photo: Training session for staff of the Economic and Organised Crime Office (EOCO), Ho regional office on 14 May 2019. (Credit: Samuel Akrofi, Ghana Case Tracking System Activity) I FIELD TEST OF NEW FEATURES & ADAPTATIONS BASED ON ON-GOING FEEDBACK ACRONYMS ADKAR Awareness, Desire, Knowledge, Ability, Reinforcement BNI Bureau of National Investigations CLIN Contract Line Item Number CTS Case Tracking System EOCO Economic and Organized Crime Office FDA Food and Drug Authority FP Focal Point GoG Government of Ghana IBG Inter-regional Bridge Group ICT Information and Communications Technology GPoS Ghana Police Service GPrS Ghana Prison Service GRA Ghana Revenue Authority JSG Judicial Service of Ghana KSA Key Stakeholder Agency LAC Legal Aid Commission MOJ/DPP Ministry of Justice/Department of Public Prosecution PWA Performance Work Statement SGI Security and Governance Initiative SIE System Implementation Engineer(s) TDA Transnational Development Associates UAT user acceptance test USAID United States Agency for International Development TABLE OF -

An Epidemiological Profile of Malaria and Its Control in Ghana

An Epidemiological Profile of Malaria and its Control in Ghana Report prepared by National Malaria Control Programme, Accra, Ghana & University of Health & Allied Sciences, Ho, Ghana & AngloGold Ashanti Malaria Control Program, Obuasi, Ghana & World Health Organization, Country Programme, Accra, Ghana & The INFORM Project Department of Public Health Research Kenya Medical Research Institute - Wellcome Trust Progamme Nairobi, Kenya Version 1.0 November 2013 Acknowledgments The authors are indebted to the following individuals from the MPHD, KEMRI-Oxford programme: Ngiang-Bakwin Kandala, Caroline Kabaria, Viola Otieno, Damaris Kinyoki, Jonesmus Mutua and Stella Kasura; we are also grateful to the help provided by Philomena Efua Nyarko, Abena Asamoabea, Osei-Akoto and Anthony Amuzu of the Ghana Statistical Service for help providing parasitological data on the MICS4 survey; Catherine Linard for assistance on modelling human population settlement; and Muriel Bastien, Marie Sarah Villemin Partow, Reynald Erard and Christian Pethas-Magilad of the WHO archives in Geneva. We acknowledge in particular all those who have generously provided unpublished data, helped locate information or the geo-coordinates of data necessary to complete the analysis of malaria risk across Ghana: Collins Ahorlu, Benjamin Abuaku, Felicia Amo-Sakyi, Frank Amoyaw, Irene Ayi, Fred Binka, David van Bodegom, Michael Cappello, Daniel Chandramohan, Amanua Chinbua, Benjamin Crookston, Ina Danquah, Stephan Ehrhardt, Johnny Gyapong, Maragret Gyapong, Franca Hartgers, Debbie Humphries, Juergen May, Seth Owusu-Agyei, Kwadwo Koram, Margaret Kweku, Frank Mockenhaupt, Philip Ricks, Sylvester Segbaya, Harry Tagbor and Mitchell Weiss. The authors also acknowledge the support and encouragement provided by the RBM Partnership, Shamwill Issah and Alistair Robb of the UK government's Department for International Development (DFID), Claude Emile Rwagacondo of the West African RBM sub- regional network and Thomas Teuscher of RBM, Geneva. -

Ghana Marine Canoe Frame Survey 2016

INFORMATION REPORT NO 36 Republic of Ghana Ministry of Fisheries and Aquaculture Development FISHERIES COMMISSION Fisheries Scientific Survey Division REPORT ON THE 2016 GHANA MARINE CANOE FRAME SURVEY BY Dovlo E, Amador K, Nkrumah B et al August 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ............................................................................................................................... 2 LIST of Table and Figures .................................................................................................................... 3 Tables............................................................................................................................................... 3 Figures ............................................................................................................................................. 3 1.0 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................. 4 1.1 BACKGROUND 1.2 AIM OF SURVEY ............................................................................................................................. 5 2.0 PROFILES OF MMDAs IN THE REGIONS ......................................................................................... 5 2.1 VOLTA REGION .......................................................................................................................... 6 2.2 GREATER ACCRA REGION ......................................................................................................... -

BY DOE HEDE RICHMOND B.Ed (MATHEMATICS) a Thesis

LOCATION OF NON-OBNOXIOUS FACILITY (HOSPITAL) IN KETU SOUTH DISTRICT BY DOE HEDE RICHMOND B.Ed (MATHEMATICS) A Thesis Submitted to the Department of Mathematics, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Award of Master of Science in Industrial Mathematics. OF COLLEGE OF SCIENCE DEPARTMENT OF MATHEMATICS SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES INSTITUTE OF DISTANCE LEARNING MAY, 2013 DECLARATION I hereby declare that this thesis is the result of my own original research with close supervisor by my supervisor and that no part of it has been presented to any institution or organization anywhere for the award of Mastersdegree. All inclusive for the work of others has been duly acknowledged. Doe Hede Richmond (PG4065110) Student …………………… ………………… Signature Date Certified by; Mr. K. F. Darkwah Supervisor’s …………………… ………………… Signature Date Certified by; Mr. K. F. Darkwah …………………… ………………… Head of Department Signature Date ii ABSTRACT The main purpose of this research is to model the location of two emergency hospitals for Ketu South district due to the newness of the district. This is to help solve the immediate health needs of the people in the district. One essential way of doing this is to locate two hospitals which will be closer to all the towns and villages in order to reduce the cost of travelling and the distances people have to access the facilities (hospital). In doing this, p-median and heuristics(RH1, RH2 and RRH) were employed to minimize the distances people have to travel to the demand point (hospitals) to access the facilities. Floyd-warshall algorithm was also adopted to connect the ten (10) selected towns and villages together. -

Small and Medium Forest Enterprises in Ghana

Small and Medium Forest Enterprises in Ghana Small and medium forest enterprises (SMFEs) serve as the main or additional source of income for more than three million Ghanaians and can be broadly categorised into wood forest products, non-wood forest products and forest services. Many of these SMFEs are informal, untaxed and largely invisible within state forest planning and management. Pressure on the forest resource within Ghana is growing, due to both domestic and international demand for forest products and services. The need to improve the sustainability and livelihood contribution of SMFEs has become a policy priority, both in the search for a legal timber export trade within the Voluntary Small and Medium Partnership Agreement (VPA) linked to the European Union Forest Law Enforcement, Governance and Trade (EU FLEGT) Action Plan, and in the quest to develop a national Forest Enterprises strategy for Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation (REDD). This sourcebook aims to shed new light on the multiple SMFE sub-sectors that in Ghana operate within Ghana and the challenges they face. Chapter one presents some characteristics of SMFEs in Ghana. Chapter two presents information on what goes into establishing a small business and the obligations for small businesses and Ghana Government’s initiatives on small enterprises. Chapter three presents profiles of the key SMFE subsectors in Ghana including: akpeteshie (local gin), bamboo and rattan household goods, black pepper, bushmeat, chainsaw lumber, charcoal, chewsticks, cola, community-based ecotourism, essential oils, ginger, honey, medicinal products, mortar and pestles, mushrooms, shea butter, snails, tertiary wood processing and wood carving. -

Evidence from a Field Experiment in Ghana

Long-run Consequences of Health Insurance Promotion When Mandates are Not Enforceable: Evidence from a Field Experiment in Ghana Patrick Opoku Asuming, Hyuncheol Bryant Kim, and Armand Sim May 2019 Abstract We study long-run selection and treatment effects of a health insurance subsidy in Ghana, where mandates are not enforceable. We randomly provide different levels of subsidy (1/3, 2/3, and full), with follow-up surveys seven months and three years after the initial intervention. We find that a one-time subsidy promotes and sustains insurance enrollment for all treatment groups, but long-run health care service utilization increases only for the partial subsidy groups. We find evidence that selection explains this pattern: those who were enrolled due to the subsidy, especially the partial subsidy, are more ill and have greater health care utilization. Key words: health insurance; sustainability; selection; randomized experiments JEL code: I1, O12 Contact the corresponding author, Hyuncheol Bryant Kim, at [email protected]; Asuming: University of Ghana Business School; Kim: Department of Policy Analysis and Management, Cornell University; Sim: Department of Applied Economics and Management, Cornell University. We thank Ama Baafra Abeberese, Douglas Almond, Diane Alexander, Jim Berry, John Cawley, Esteban Mendez Chacon, Pierre-Andre Chiappori, Giacomo De Giorgi, Supreet Kaur, Robert Kaestner, Don Kenkel, Daeho Kim, Michael Kremer, Wojciech Kopczuk, Leigh Linden, Corrine Low, Doug Miller, Sangyoon Park, Seollee Park, Cristian Pop-Eleches, Bernard Salanie, and seminar participants at Columbia University, Cornell University, Seoul National University, and the NEUDC. This research was supported by the Cornell Population Center and Social Enterprise Development Foundation, Ghana (SEND-Ghana)." Armand Sim gratefully acknowledges financial support from the Indonesia Education Endowment Fund. -

“I Want to Go to School, but I Can't”: Examining the Factors That Impact

―I Want to go to School, but I Can‘t‖: Examining the Factors that Impact the Anlo Ewe Girl Child‘s Formal Education in Abor, Ghana A dissertation presented to the faculty of The Gladys W. and David H. Patton College of Education and Human Services of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Karen Yawa Agbemabiese-Grooms August 2011 © 2011 Karen Yawa Agbemabiese-Grooms. All Rights Reserved. 2 This dissertation titled ―I Want to go to School, but I Can‘t‖: Examining the Factors that Impact the Anlo Ewe Girl Child‘s Formal Education in Abor, Ghana by KAREN YAWA AGBEMABIESE-GROOMS has been approved for the Department of Educational Studies and The Gladys W. and David H. Patton College of Education and Human Services by Jaylynne N. Hutchinson Associate Professor of Educational Studies Renée A. Middleton Dean, The Gladys W. and David H. Patton College of Education and Human Services 3 Abstract AGBEMABIESE-GROOMS, KAREN YAWA, Ph.D., August 2011, Curriculum and Instruction, Cultural Studies ―I Want to go to School, but I Can‘t‖: Examining the Factors that Impact the Anlo Ewe Girl Child‘s Formal Education in Abor, Ghana (pp. 306) Director of Dissertation: Jaylynne N. Hutchinson This study explored factors that impact the Anlo Ewe girl child‘s formal educational outcomes. The issue of female and girl child education is a global concern even though its undesirable impact is more pronounced in African rural communities (Akyeampong, 2001; Nukunya, 2003). Although educational research in Ghana indicates that there are variables that limit girl‘s access to formal education, educational improvements are not consistent in remedying the gender inequities in education. -

Establishing an Index Insurance Trigger for Crop Loss in Northern Ghana

ESTABLISHLISING AN IINDEXNDEX INSURANCE TRIGGERS FOR CROP LOSS IN NORTHERN GHANA The Katie School of Insurance RESEARCH P A P E R N o . 7 SEPTEMBER 2011 ESTABLISHING AN INDEX of income for 60 percent of the population. INSURANCE TRIGGER FOR CROP Agricultural production depends on a number of LOSS IN NORTHERN GHANA factors including economic, political, technological, as well as factors such as disease, fires, and certainly THE KATIE SCHOOL OF weather. Rainfall and temperature have a significant INSURANCE 1 effect on agriculture, especially crops. Although every part of the world has its own weather patterns, and managing the risks associated with these patterns has ABSTRACT always been a part of life as a farmer, recent changes As a consequence of climate change, agriculture in in weather cycles resulting from increasing climate many parts of the world has become a riskier business change have increased the risk profile for farming and activity. Given the dependence on agriculture in adversely affected the ability of farmers to get loans. developing countries, this increased risk has a Farmers in developing countries may respond to losses potentially dramatic effect on the lives of people in ways that affect their future livelihoods such as throughout the developing world especially as it selling off valuable assets, or removing their children relates to their financial inclusion and sustainable from school and hiring them out to others for work. access to capital. This study analyzes the relationships They may also be unable to pay back loans in a timely between rainfall per crop gestation period (planting – manner, which makes rural banks and even harvesting) and crop yields and study the likelihood of microfinance institutions reluctant to provide them with crop yield losses. -

A Situation Analysis of Ghanaian Children and Women

MoWAC & UNICEF SITUATION ANALYSIS REPORT A Situation Analysis of Ghanaian Children and Women A Call for Reducing Disparities and Improving Equity UNICEF and Ministry of Women & Children’s Affairs, Ghana October 2011 SITUATION ANALYSIS REPORT MoWAC & UNICEF MoWAC & UNICEF SITUATION ANALYSIS REPORT PREFACE CONTENTS Over the past few years, Ghana has earned international credit as a model of political stability, good governance and democratic openness, with well-developed institutional capacities and an overall Preface II welcoming environment for the advancement and protection of women’s and children’s interests and rights. This Situation Analysis of Ghanaian children and women provide the status of some of List of Tables and Figures V the progress made, acknowledging that children living in poverty face deprivations of many of their List of Acronyms and Abbreviations VI rights, namely the rights to survive, to develop, to participate and to be protected. The report provides Map of Ghana IX comprehensive overview encompassing the latest data in economy, health, education, water and Executive Summary X sanitation, and child and social protection. What emerges is a story of success, challenges and Introduction 1 opportunities. PART ONE: The indings show that signiicant advances have been made towards the realisation of children’s rights, with Ghana likely to meet some of the MDGs, due to the right investment choices, policies THE COUNTRY CONTEXT and priorities. For example, MDG1a on reducing the population below the poverty line has been met; school enrolment is steadily increasing, the gender gap is closing at the basic education level, Chapter One: child mortality has sharply declined, full immunization coverage has nearly been achieved, and the The Governance Environment 6 MDG on access to safe water has been met. -

University of Ghana

University of Ghana http://ugspace.ug.edu.gh UNIVERSITY OF GHANA CENTRE FOR SOCIAL POLICY STUDIES A POLITICAL ECONOMY ANALYSIS OF GHANA’S SCHOOL FEEDING PROGRAMME BY OBED OPOKU AFRANE 10308813 THIS DISSERTATION IS SUBMITTED TO THE UNIVERSITY OF GHANA, LEGON IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENT FOR THE AWARD OF MA SOCIAL POLICY STUDIES DEGREE. JULY, 2015 University of Ghana http://ugspace.ug.edu.gh DECLARATION I, Obed Opoku Afrane, hereby declare that except the references to other people‟s work which were duly acknowledged, this dissertation is the result of my own independent work carried out at the Centre for Social Policy Studies, University of Ghana, Legon, under the supervision of Dr. Seidu M. Alidu and that it has not been presented in whole or in part elsewhere for the award of another degree. ……………………………… ………………………... OBED OPOKU AFRANE DATE (10308813) ……………………………….. ………………………… DR. SEIDU M. ALIDU DATE (SUPERVISOR) i University of Ghana http://ugspace.ug.edu.gh DEDICATION I dedicate this work to my mother Gladys S. Bonsu, my grandmother Afia Fowaah, and my uncle Mr. William Yeboah. It is also dedicated to the memory of my late aunty, Ms. Angelina Owusu Achiaa who until her death provided unflinching support to my upbringing and education at the University of Ghana. God richly bless them all. ii University of Ghana http://ugspace.ug.edu.gh ACKNOWLEDGEMENT First and foremost I give thanks to the Almighty God for His abundant mercies and favour upon my life, and the continuous blessings showered on me by bringing wonderful people into my life. I am most grateful to my supervisor, Dr. -

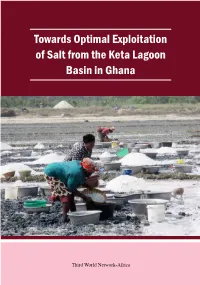

Towards Optimal Exploitation of Salt from the Keta Lagoon Basin in Ghana

Towards Optimal Exploitation of Salt from the Keta Lagoon Basin in Ghana Third World Network-Africa Towards Optimal Exploitation of Salt from the Keta Lagoon Basin in Ghana Third World Network-Africa Accra, Ghana Towards Optimal Exploitation of Salt from the Keta Lagoon Basin in Ghana is published by Third World Network-Africa No 9 Asmara Street, East Legon, Accra Box AN 19452, Accra, Ghana Tel: 233-302-500419/503669/511189 Website: www.twnafrica.org Email: [email protected] Copyright © Third World Network-Africa, 2017 ISBN: 9988271305 Foreword Ghana has the best endowment for and is the biggest producer of solar salt in West Africa. The bulk of the production and export comes from arti- sanal and small scale (ASM) producers. This is a research report on strug- gles between a large scale salt company and some communities around the Keta Lagoon in Ghana. At the centre of the conflict is the disruption of the livelihoods of the communities by the award of a concession to a foreign investor for large scale salt production, an act which has expropri- ated what the communities see as the commons around the lagoon where for generations they have carried out livelihood activities which combine fishing, farming and salt production. The Keta Lagoon is the second most important salt producing area in Ghana and the conflict, in which Police protecting the company have shot some locals dead, is emblematic of the wider problem of the status of ASM across Africa with many governments even when faced with the huge potential of ASM avoid offering support to these predominantly lo- cal entrepreneurs and reflexively choose to support large scale, usually foreign, investors. -

Certified Electrical Wiring Professionals Volta Regional Register Certification No

CERTIFIED ELECTRICAL WIRING PROFESSIONALS VOLTA REGIONAL REGISTER CERTIFICATION NO. NAME PHONE NUMBER PLACE OF WORK PIN NUMBER CLASS 1 ABOTSI FELIX GBOMOSHOW 0246296692 DENU EC/CEWP1/06/18/0020 DOMESTIC 2 ACKUAYI JOSEPH DOTSE 0244114574 ANYAKO EC/CEWP1/12/14/0021 DOMESTIC 3 ADANU KWASHIE WISDOM 0245768361 DZODZE, VOLTA REGION EC/CEWP1/06/16/0025 DOMESTIC 4 ADEVOR FRANCIS 0241658220 AVE-DAKPA EC/CEWP1/12/19/0013 DOMESTIC 5 ADISENU ADOLF QUARSHIE 0246627858 AGBOZUME EC/CEWP1/12/14/0039 DOMESTIC 6 ADJEI-DZIDE FRANKLIN ELENUJOR NOVA KING 0247928015 KPANDO, VOLTA EC/CEWP1/12/18/0025 DOMESTIC 7 ADOR AFEAFA 0246740864 SOGAKOPE EC/CEWP1/12/19/0018 DOMESTIC 8 ADZALI PAUL KOMLA 0245789340 TAFI MADOR EC/CEWP1/12/14/0054 DOMESTIC 9 ADZAMOA DIVINE MENSAH 0242769759 KRACHI EC/CEWP1/12/18/0031 DOMESTIC 10 ADZRAKU DODZI 0248682929 ALAVANYO EC/CEWP1/12/18/0033 DOMESTIC 11 AFADZINOO MIDAWO 0243650148 ANLO AFIADENYIGBA EC/CEWP1/06/14/0174 DOMESTIC 12 AFUTU BRIGHT 0245156375 HOHOE EC/CEWP1/12/18/0035 DOMESTIC 13 AGBALENYO CHRISTIAN KOFI 0285167920 ANLOKODZI, HO EC/CEWP1/12/13/0024 DOMESTIC 14 AGBAVE KINDNESS JERRY 0505231782 AKATSI, VOLTA REGION EC/CEWP1/12/15/0040 DOMESTIC 15 AGBAVOR SIMON 0243436475 KPANDO EC/CEWP1/12/16/0050 DOMESTIC 16 AGBAVOR VICTOR KWAKU 0244298648 AKATSI EC/CEWP1/06/14/0177 DOMESTIC 17 AGBEKO MICHEAL 0557912356 SOGAKOFE EC/CEWP1/06/19/0095 DOMESTIC 18 AGBEMADE SIMON 0244049157 DABALA, SOGAKOPE,VOLTA REGIONEC/CEWP1/12/16/0052 DOMESTIC 19 AGBEMAFLE MICHAEL 0248481385 HOHOE EC/CEWP1/12/18/0038 DOMESTIC 20 AGBENORKU KWAKU EMMANUEL 0506820579 DABALA JUNCTION- SOGAKOPE, VOLEC/CEWP1/12/17/0053 DOMESTIC 21 AGBENYEFIA SENANU FRANCIS 0244937008 CENTRAL TONGU EC/CEWP1/06/17/0046 DOMESTIC 22 AGBODOVI K.