Jugular Foramen Tumors: Diagnosis and Treatment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Morphological Study of Jugular Foramen

Vikas. C. Desai et al /J. Pharm. Sci. & Res. Vol. 9(4), 2017, 456-458 A Morphological Study of Jugular Foramen Vikas. C. Desai1, Pavan P Havaldar2 1. Asst. Prof, Department of Dentistry, BLDE University’s,Shri. B. M. Patil Medical College Hospital and Research Centre,Bijapur – 586103, Karnataka State. 2. Assistant Professor of Anatomy, Gadag Institute of Medical Sciences, Mallasamudra, Mulgund Road, Gadag, Karnataka, India. Abstract Jugular foramen is a large aperture in the base of the skull. It is located behind the carotid canal and is formed by the petrous part of the temporal bone and behind by the occipital bone. The jugular foramen is the main route of venous outflow from the skull and is characterised by laterality based on the predominance of one of the sides. Sigmoid sinus continues as internal jugular vein in posterior part of jugular foramen. Ligation of the internal jugular is sometimes performed during radical neck dissection with the risk of venous infarction, which some adduce to be due to ligation of the dominant internal jugular vein. It is generally said that although the Jugular foramen is larger on the right side compared to the left, its size as well as its height and volume vary in different racial groups and sexes. The foramen’s complex shape, its formation by two bones, and the numerous nerves and venous channels that pass through it further compound its anatomy. The present study was undertaken in 263(526 sides) different medical and dental institutions in Karnataka, India. Out of 263 skulls in 61.21% of cases the right foramina were larger than the left, in 13.68% of cases the left foramina were larger than the right and in 25.09% cases were equal on both sides. -

Recurrent Targetoid Hemosiderotic Hemangioma in a 26-Year-Old Man

CASE REPORT Recurrent Targetoid Hemosiderotic Hemangioma in a 26-Year-Old Man LT Sarah Broski Gendernalik, DO, MC (FS), USN LT James D. Gendernalik, DO, MC (FS), USN A 26-year-old previously healthy man presented with a 6-mm violaceous papule that had a surrounding 1.5-cm annular, nonblanching, erythematous halo on the right-sided flank. The man reported the lesion had been recurring for 4 to 5 years, flaring every 4 to 5 months and then slowly disap - pearing until the cycle recurred. Targetoid hemosiderotic hemangioma was clinically diagnosed. The lesion was removed by means of elliptical excision and the condition resolved. The authors discuss the clinical appearance, his - tology, and etiology of targetoid hemosiderotic heman - giomas. J Am Osteopath Assoc . 2011;111(2);117-118 argetoid hemosiderotic hemangiomas (THHs) are a com - Tmonly misdiagnosed presentation encountered in the primary care setting. In the present case report, we aim to pro - Figure. A 6-mm violaceous papule with a surrounding 1.5-cm annular, nonblanching, erythematous halo in a 26-year-old man. vide general practitioners with an understanding of the clin - ical appearance, pathology, and prognosis of THH. Report of Case A 26-year-old previously healthy man presented to our primary around it and itched and burned each time it developed. The care clinic with a 6-mm violaceous papule with a surrounding lesion faded completely to normal-appearing skin between 1.5-cm annular, nonblanching, erythematous halo on the right- episodes, without evidence of a papule or postinflammatory sided flank ( Figure ). The patient stated that the lesion had hyperpigmentation. -

Tumors and Tumor-Like Lesions of Blood Vessels 16 F.Ramon

16_DeSchepper_Tumors_and 15.09.2005 13:27 Uhr Seite 263 Chapter Tumors and Tumor-like Lesions of Blood Vessels 16 F.Ramon Contents 42]. There are two major classification schemes for vas- cular tumors. That of Enzinger et al. [12] relies on 16.1 Introduction . 263 pathological criteria and includes clinical and radiolog- 16.2 Definition and Classification . 264 ical features when appropriate. On the other hand, the 16.2.1 Benign Vascular Tumors . 264 classification of Mulliken and Glowacki [42] is based on 16.2.1.1 Classification of Mulliken . 264 endothelial growth characteristics and distinguishes 16.2.1.2 Classification of Enzinger . 264 16.2.1.3 WHO Classification . 265 hemangiomas from vascular malformations. The latter 16.2.2 Vascular Tumors of Borderline classification shows good correlation with the clinical or Intermediate Malignancy . 265 picture and imaging findings. 16.2.3 Malignant Vascular Tumors . 265 Hemangiomas are characterized by a phase of prolif- 16.2.4 Glomus Tumor . 266 eration and a stationary period, followed by involution. 16.2.5 Hemangiopericytoma . 266 Vascular malformations are no real tumors and can be 16.3 Incidence and Clinical Behavior . 266 divided into low- or high-flow lesions [65]. 16.3.1 Benign Vascular Tumors . 266 Cutaneous and subcutaneous lesions are usually 16.3.2 Angiomatous Syndromes . 267 easily diagnosed and present no significant diagnostic 16.3.3 Hemangioendothelioma . 267 problems. On the other hand, hemangiomas or vascular 16.3.4 Angiosarcomas . 268 16.3.5 Glomus Tumor . 268 malformations that arise in deep soft tissue must be dif- 16.3.6 Hemangiopericytoma . -

The Health-Related Quality of Life of Sarcoma Patients and Survivors In

Cancers 2020, 12 S1 of S7 Supplementary Materials The Health-Related Quality of Life of Sarcoma Patients and Survivors in Germany—Cross-Sectional Results of A Nationwide Observational Study (PROSa) Martin Eichler, Leopold Hentschel, Stephan Richter, Peter Hohenberger, Bernd Kasper, Dimosthenis Andreou, Daniel Pink, Jens Jakob, Susanne Singer, Robert Grützmann, Stephen Fung, Eva Wardelmann, Karin Arndt, Vitali Heidt, Christine Hofbauer, Marius Fried, Verena I. Gaidzik, Karl Verpoort, Marit Ahrens, Jürgen Weitz, Klaus-Dieter Schaser, Martin Bornhäuser, Jochen Schmitt, Markus K. Schuler and the PROSa study group Includes Entities We included sarcomas according to the following WHO classification. - Fletcher CDM, World Health Organization, International Agency for Research on Cancer, editors. WHO classification of tumours of soft tissue and bone. 4th ed. Lyon: IARC Press; 2013. 468 p. (World Health Organization classification of tumours). - Kurman RJ, International Agency for Research on Cancer, World Health Organization, editors. WHO classification of tumours of female reproductive organs. 4th ed. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2014. 307 p. (World Health Organization classification of tumours). - Humphrey PA, Moch H, Cubilla AL, Ulbright TM, Reuter VE. The 2016 WHO Classification of Tumours of the Urinary System and Male Genital Organs—Part B: Prostate and Bladder Tumours. Eur Urol. 2016 Jul;70(1):106–19. - World Health Organization, Swerdlow SH, International Agency for Research on Cancer, editors. WHO classification of tumours of haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues: [... reflects the views of a working group that convened for an Editorial and Consensus Conference at the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), Lyon, October 25 - 27, 2007]. 4. ed. -

Vascular Tumors and Malformations of the Orbit

14 Vascular Tumors Kaan Gündüz and Zeynel A. Karcioglu ascular tumors and malformations of the orbit VIII related antigen (v,w,f), CV141 (endothelium, comprise an important group of orbital space- mesothelium, and squamous cells), and VEGFR-3 Voccupying lesions. Reviews indicate that vas- (channels, neovascular endothelium). None of the cell cular lesions account for 6.2 to 12.0% of all histopatho- markers is absolutely specific in its application; a com- logically documented orbital space-occupying lesions bination is recommended in difficult cases. CD31 is (Table 14.1).1–5 There is ultrastructural and immuno- the most often used endothelial cell marker, with pos- histochemical evidence that capillary and cavernous itive membrane staining pattern in over 90% of cap- hemangiomas, lymphangioma, and other vascular le- illary hemangiomas, cavernous hemangiomas, and an- sions are of different nosologic origins, yet in many giosarcomas; CD34 is expressed only in about 50% of patients these entities coexist. Hence, some prefer to endothelial cell tumors. Lymphangioma pattern, on use a single umbrella term, “vascular hamartomatous the other hand, is negative with CD31 and CD34, lesions” to identify these masses, with the qualifica- but, it is positive with VEGFR-3. VEGFR-3 expression tion that, in a given case, one tissue element may pre- is also seen in Kaposi sarcoma and in neovascular dominate.6 For example, an “infantile hemangioma” endothelium. In hemangiopericytomas, the tumor may contain a few caverns or intertwined abnormal cells are typically positive for vimentin and CD34 and blood vessels, but its predominating component is negative for markers of endothelia (factor VIII, CD31, usually capillary hemangioma. -

Glomus Tumor in the Floor of the Mouth: a Case Report and Review of the Literature Haixiao Zou1,2, Li Song1, Mengqi Jia2,3, Li Wang4 and Yanfang Sun2,3*

Zou et al. World Journal of Surgical Oncology (2018) 16:201 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12957-018-1503-6 CASEREPORT Open Access Glomus tumor in the floor of the mouth: a case report and review of the literature Haixiao Zou1,2, Li Song1, Mengqi Jia2,3, Li Wang4 and Yanfang Sun2,3* Abstract Background: Glomus tumors are rare benign neoplasms that usually occur in the upper and lower extremities. Oral cavity involvement is exceptionally rare, with only a few cases reported to date. Case presentation: A 24-year-old woman with complaints of swelling in the left floor of her mouth for 6 months was referred to our institution. Her swallowing function was slightly affected; however, she did not have pain or tongue paralysis. Enhanced computed tomography revealed a 2.8 × 1.8 × 2.1 cm-sized well-defined, solid, heterogeneous nodule above the mylohyoid muscle. The mandible appeared to be uninvolved. The patient underwent surgery via an intraoral approach; histopathological examination revealed a glomus tumor. The patient has had no evidence of recurrence over 4 years of follow-up. Conclusions: Glomus tumors should be considered when patients present with painless nodules in the floor of the mouth. Keywords: Glomus tumor, Floor of mouth, Oral surgery Background Case presentation Theglomusbodyisaspecialarteriovenousanasto- A 24-year-old woman with a 6-month history of swelling mosisandfunctionsinthermalregulation.Glomustu- in the left floor of her mouth was referred to our institu- mors are rare, benign, mesenchymal tumors that tion. Although she experienced slight difficulty in swal- originate from modified smooth muscle cells of the lowing, she did not experience pain or tongue paralysis. -

Biomechanical Analysis of Skull Trauma and Opportunity In

Distriquin et al. European Radiology Experimental (2020) 4:66 European Radiology https://doi.org/10.1186/s41747-020-00194-x Experimental NARRATIVE REVIEW Open Access Biomechanical analysis of skull trauma and opportunity in neuroradiology interpretation to explain the post- concussion syndrome: literature review and case studies presentation Yannick Distriquin1, Jean-Marc Vital2 and Bruno Ella3* Abstract Traumatic head injuries are one of the leading causes of emergency worldwide due to their frequency and associated morbidity. The circumstances of their onset are often sports activities or road accidents. Numerous studies analysed post-concussion syndrome from a psychiatric and metabolic point of view after a mild head trauma. The aim was to help understand how the skull can suffer a mechanical deformation during a mild cranial trauma, and if it can explain the occurrence of some post-concussion symptoms. A multi-step electronic search was performed, using the following keywords: biomechanics properties of the skull, three-dimensional computed tomography of head injuries, statistics on skull injuries, and normative studies of the skull base. We analysed studies related to the observation of the skull after mild head trauma. The analysis of 23 studies showed that the cranial sutures could be deformed even during a mild head trauma. The skull base is a major site of bone shuffle. Three-dimensional computed tomography can help to understand some post-concussion symptoms. Four case studies showed stenosis of jugular foramen and petrous bone asymmetries who can correlate with concussion symptomatology. In conclusion, the skull is a heterogeneous structure that can be deformed even during a mild head trauma. -

Benign Hemangiomas

TUMORS OF BLOOD VESSELS CHARLES F. GESCHICKTER, M.D. (From tke Surgical Palkological Laboratory, Department of Surgery, Johns Hopkins Hospital and University) AND LOUISA E. KEASBEY, M.D. (Lancaster Gcaeral Hospital, Lancuster, Pennsylvania) Tumors of the blood vessels are perhaps as common as any form of neoplasm occurring in the human body. The greatest number of these lesions are benign angiomas of the body surfaces, small elevated red areas which remain without symptoms throughout life and are not subjected to treatment. Larger tumors of this type which undergb active growth after birth or which are situated about the face or oral cavity, where they constitute cosmetic defects, are more often the object of surgical removal. The majority of the vascular tumors clinically or pathologically studied fall into this latter group. Benign angiomas of similar pathologic nature occur in all of the internal viscera but are most common in the liver, where they are disclosed usually at autopsy. Angiomas of the bone, muscle, and the central nervous system are of less common occurrence, but, because of the symptoms produced, a higher percentage are available for study. Malignant lesions of the blood vessels are far more rare than was formerly supposed. An occasional angioma may metastasize following trauma or after repeated recurrences, but less than 1per cent of benign angiomas subjected to treatment fall into this group. I Primarily ma- lignant tumors of the vascular system-angiosarcomas-are equally rare. The pathological criteria for these growths have never been ade- quately established, and there is no general agreement as to this par- ticular form of tumor. -

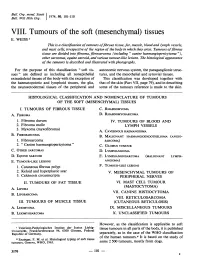

Mesenchymal) Tissues E

Bull. Org. mond. San 11974,) 50, 101-110 Bull. Wid Hith Org.j VIII. Tumours of the soft (mesenchymal) tissues E. WEISS 1 This is a classification oftumours offibrous tissue, fat, muscle, blood and lymph vessels, and mast cells, irrespective of the region of the body in which they arise. Tumours offibrous tissue are divided into fibroma, fibrosarcoma (including " canine haemangiopericytoma "), other sarcomas, equine sarcoid, and various tumour-like lesions. The histological appearance of the tamours is described and illustrated with photographs. For the purpose of this classification " soft tis- autonomic nervous system, the paraganglionic struc- sues" are defined as including all nonepithelial tures, and the mesothelial and synovial tissues. extraskeletal tissues of the body with the exception of This classification was developed together with the haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues, the glia, that of the skin (Part VII, page 79), and in describing the neuroectodermal tissues of the peripheral and some of the tumours reference is made to the skin. HISTOLOGICAL CLASSIFICATION AND NOMENCLATURE OF TUMOURS OF THE SOFT (MESENCHYMAL) TISSUES I. TUMOURS OF FIBROUS TISSUE C. RHABDOMYOMA A. FIBROMA D. RHABDOMYOSARCOMA 1. Fibroma durum IV. TUMOURS OF BLOOD AND 2. Fibroma molle LYMPH VESSELS 3. Myxoma (myxofibroma) A. CAVERNOUS HAEMANGIOMA B. FIBROSARCOMA B. MALIGNANT HAEMANGIOENDOTHELIOMA (ANGIO- 1. Fibrosarcoma SARCOMA) 2. " Canine haemangiopericytoma" C. GLOMUS TUMOUR C. OTHER SARCOMAS D. LYMPHANGIOMA D. EQUINE SARCOID E. LYMPHANGIOSARCOMA (MALIGNANT LYMPH- E. TUMOUR-LIKE LESIONS ANGIOMA) 1. Cutaneous fibrous polyp F. TUMOUR-LIKE LESIONS 2. Keloid and hyperplastic scar V. MESENCHYMAL TUMOURS OF 3. Calcinosis circumscripta PERIPHERAL NERVES II. TUMOURS OF FAT TISSUE VI. -

8.5 X12.5 Doublelines.P65

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-87409-0 - Modern Soft Tissue Pathology: Tumors and Non-Neoplastic Conditions Edited by Markku Miettinen Index More information Index abdominal ependymoma, 744 mucinous cystadenocarcinoma, 631 adult fibrosarcoma (AF), 364–365, 1026 abdominal extrauterine smooth muscle ovarian adenocarcinoma, 72, 79 adult granulosa cell tumor, 523–524 tumors, 79 pancreatic adenocarcinoma, 846 clinical features, 523 abdominal inflammatory myofibroblastic pulmonary adenocarcinoma, 51 genetics, 524 tumors, 297–298 renal adenocarcinoma, 67 pathology, 523–524 abdominal leiomyoma, 467, 477 serous cystadenocarcinoma, 631 adult rhabdomyoma, 548–549 abdominal leiomyosarcoma. See urinary bladder/urogenital tract clinical features, 548 gastrointestinal stromal tumor adenocarcinoma, 72, 401 differential diagnosis, 549 (GIST) uterine adenocarcinomas, 72 genetics, 549 abdominal perivascular epithelioid cell tumors adenofibroma, 523 pathology, 548–549 (PEComas), 542 adenoid cystic carcinoma, 1035 aggressive angiomyxoma (AAM), 514–518 abdominal wall desmoids, 244 adenomatoid tumor, 811–813 clinical features, 514–516 acquired elastotic hemangioma, 598 adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) gene, 143 differential diagnosis, 518 acquired tufted angioma, 590 adenosarcoma (mullerian¨ adenosarcoma), 523 genetics, 518 acral arteriovenous tumor, 583 adipocytic lesions (cytology), 1017–1022 pathology, 516 acral myxoinflammatory fibroblastic sarcoma atypical lipomatous tumor/well- aggressive digital papillary adenocarcinoma, (AMIFS), 365–370, 1026 differentiated -

The Interperiosteodural Concept Applied to the Jugular Foramen and Its Compartmentalization

LABORATORY INVESTIGATION J Neurosurg 129:770–778, 2018 The interperiosteodural concept applied to the jugular foramen and its compartmentalization Florian Bernard, MD,1 Ilyess Zemmoura, MD, PhD,2–4 Jean Philippe Cottier, MD, PhD,2,5 Henri-Dominique Fournier, MD, PhD,1,6 Louis-Marie Terrier, MD, MSc,2–4 and Stéphane Velut, MD, PhD2–4 1Department of Neurosurgery, CHU Angers; 2Université François–Rabelais de Tours, Inserm, Imagerie et Cerveau, UMR U930, Tours; 3Anatomy Laboratory, Faculté de Médecine, Tours; Departments of 4Neurosurgery and 5Neuroradiology, CHRU de Tours; and 6Anatomy Laboratory, Faculté de Médecine, Angers, France OBJECTIVE The dura mater is made of 2 layers: the endosteal layer (outer layer), which is firmly attached to the bone, and the meningeal layer (inner layer), which directly covers the brain and spinal cord. These 2 dural layers join together in most parts of the skull base and cranial convexity, and separate into the orbital and perisellar compartments or into the spinal epidural space to form the extradural neural axis compartment (EDNAC). The EDNAC contains fat and/or venous blood. The aim of this dissection study was to anatomically verify the concept of the EDNAC by focusing on the dural layers surrounding the jugular foramen area. METHODS The authors injected 10 cadaveric heads (20 jugular foramina) with colored latex and fixed them in formalin. The brainstem and cerebellum of 7 specimens were cautiously removed to allow a superior approach to the jugular fora- men. Special attention was paid to the meningeal architecture of the jugular foramen, the petrosal inferior sinus and its venous confluence with the sigmoid sinus, and the glossopharyngeal, vagus, and accessory nerves. -

Head and Neck Kaposi Sarcoma: Clinicopathological Analysis of 11 Cases

Head and Neck Pathology https://doi.org/10.1007/s12105-018-0902-x ORIGINAL PAPER Head and Neck Kaposi Sarcoma: Clinicopathological Analysis of 11 Cases Abbas Agaimy1 · Sarina K. Mueller2 · Thomas Harrer3 · Sebastian Bauer4 · Lester D. R. Thompson5 Received: 24 January 2018 / Accepted: 26 February 2018 © Springer Science+Business Media, LLC, part of Springer Nature 2018 Abstract Kaposi sarcoma (KS) of the head and neck area is uncommon with limited published case series. Our routine and consulta- tion files were reviewed for histologically and immunohistochemically proven KS affecting any cutaneous or mucosal head and neck site. Ten males and one female aged 42–78 years (median, 51 years; mean, 52 years) were retrieved. Eight patients were HIV-positive and three were HIV-negative. The affected sites were skin (n = 5), oral/oropharyngeal mucosa (n = 5), and lymph nodes (n = 3) in variable combination. The ear (pinna and external auditory canal) was affected in two cases; both were HIV-negative. Multifocal non-head and neck KS was reported in 50% of patients. At last follow-up (12–94 months; median, 46 months), most of patients were either KS-free (n = 8) or had ongoing remission under systemic maintenance therapy (n = 2). One patient was alive with KS (poor compliance). Histopathological evaluation showed classical features of KS. One case was predominantly sarcomatoid with prominent inflammation mimicking undifferentiated sarcoma. Immunohisto- chemistry showed consistent expression of CD31, CD34, ERG, D2-40 and HHV8 in all cases. This is one of the few series devoted to head and neck KS showing high prevalence of HIV-positivity, but also unusual presentations in HIV-negative patients with primary origin in the skin of the ear and the auditory canal.