Head and Neck Kaposi Sarcoma: Clinicopathological Analysis of 11 Cases

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Recurrent Targetoid Hemosiderotic Hemangioma in a 26-Year-Old Man

CASE REPORT Recurrent Targetoid Hemosiderotic Hemangioma in a 26-Year-Old Man LT Sarah Broski Gendernalik, DO, MC (FS), USN LT James D. Gendernalik, DO, MC (FS), USN A 26-year-old previously healthy man presented with a 6-mm violaceous papule that had a surrounding 1.5-cm annular, nonblanching, erythematous halo on the right-sided flank. The man reported the lesion had been recurring for 4 to 5 years, flaring every 4 to 5 months and then slowly disap - pearing until the cycle recurred. Targetoid hemosiderotic hemangioma was clinically diagnosed. The lesion was removed by means of elliptical excision and the condition resolved. The authors discuss the clinical appearance, his - tology, and etiology of targetoid hemosiderotic heman - giomas. J Am Osteopath Assoc . 2011;111(2);117-118 argetoid hemosiderotic hemangiomas (THHs) are a com - Tmonly misdiagnosed presentation encountered in the primary care setting. In the present case report, we aim to pro - Figure. A 6-mm violaceous papule with a surrounding 1.5-cm annular, nonblanching, erythematous halo in a 26-year-old man. vide general practitioners with an understanding of the clin - ical appearance, pathology, and prognosis of THH. Report of Case A 26-year-old previously healthy man presented to our primary around it and itched and burned each time it developed. The care clinic with a 6-mm violaceous papule with a surrounding lesion faded completely to normal-appearing skin between 1.5-cm annular, nonblanching, erythematous halo on the right- episodes, without evidence of a papule or postinflammatory sided flank ( Figure ). The patient stated that the lesion had hyperpigmentation. -

Vascular Tumors and Malformations of the Orbit

14 Vascular Tumors Kaan Gündüz and Zeynel A. Karcioglu ascular tumors and malformations of the orbit VIII related antigen (v,w,f), CV141 (endothelium, comprise an important group of orbital space- mesothelium, and squamous cells), and VEGFR-3 Voccupying lesions. Reviews indicate that vas- (channels, neovascular endothelium). None of the cell cular lesions account for 6.2 to 12.0% of all histopatho- markers is absolutely specific in its application; a com- logically documented orbital space-occupying lesions bination is recommended in difficult cases. CD31 is (Table 14.1).1–5 There is ultrastructural and immuno- the most often used endothelial cell marker, with pos- histochemical evidence that capillary and cavernous itive membrane staining pattern in over 90% of cap- hemangiomas, lymphangioma, and other vascular le- illary hemangiomas, cavernous hemangiomas, and an- sions are of different nosologic origins, yet in many giosarcomas; CD34 is expressed only in about 50% of patients these entities coexist. Hence, some prefer to endothelial cell tumors. Lymphangioma pattern, on use a single umbrella term, “vascular hamartomatous the other hand, is negative with CD31 and CD34, lesions” to identify these masses, with the qualifica- but, it is positive with VEGFR-3. VEGFR-3 expression tion that, in a given case, one tissue element may pre- is also seen in Kaposi sarcoma and in neovascular dominate.6 For example, an “infantile hemangioma” endothelium. In hemangiopericytomas, the tumor may contain a few caverns or intertwined abnormal cells are typically positive for vimentin and CD34 and blood vessels, but its predominating component is negative for markers of endothelia (factor VIII, CD31, usually capillary hemangioma. -

Benign Hemangiomas

TUMORS OF BLOOD VESSELS CHARLES F. GESCHICKTER, M.D. (From tke Surgical Palkological Laboratory, Department of Surgery, Johns Hopkins Hospital and University) AND LOUISA E. KEASBEY, M.D. (Lancaster Gcaeral Hospital, Lancuster, Pennsylvania) Tumors of the blood vessels are perhaps as common as any form of neoplasm occurring in the human body. The greatest number of these lesions are benign angiomas of the body surfaces, small elevated red areas which remain without symptoms throughout life and are not subjected to treatment. Larger tumors of this type which undergb active growth after birth or which are situated about the face or oral cavity, where they constitute cosmetic defects, are more often the object of surgical removal. The majority of the vascular tumors clinically or pathologically studied fall into this latter group. Benign angiomas of similar pathologic nature occur in all of the internal viscera but are most common in the liver, where they are disclosed usually at autopsy. Angiomas of the bone, muscle, and the central nervous system are of less common occurrence, but, because of the symptoms produced, a higher percentage are available for study. Malignant lesions of the blood vessels are far more rare than was formerly supposed. An occasional angioma may metastasize following trauma or after repeated recurrences, but less than 1per cent of benign angiomas subjected to treatment fall into this group. I Primarily ma- lignant tumors of the vascular system-angiosarcomas-are equally rare. The pathological criteria for these growths have never been ade- quately established, and there is no general agreement as to this par- ticular form of tumor. -

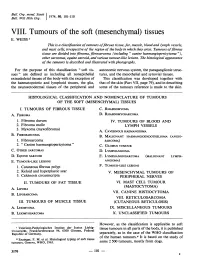

Mesenchymal) Tissues E

Bull. Org. mond. San 11974,) 50, 101-110 Bull. Wid Hith Org.j VIII. Tumours of the soft (mesenchymal) tissues E. WEISS 1 This is a classification oftumours offibrous tissue, fat, muscle, blood and lymph vessels, and mast cells, irrespective of the region of the body in which they arise. Tumours offibrous tissue are divided into fibroma, fibrosarcoma (including " canine haemangiopericytoma "), other sarcomas, equine sarcoid, and various tumour-like lesions. The histological appearance of the tamours is described and illustrated with photographs. For the purpose of this classification " soft tis- autonomic nervous system, the paraganglionic struc- sues" are defined as including all nonepithelial tures, and the mesothelial and synovial tissues. extraskeletal tissues of the body with the exception of This classification was developed together with the haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues, the glia, that of the skin (Part VII, page 79), and in describing the neuroectodermal tissues of the peripheral and some of the tumours reference is made to the skin. HISTOLOGICAL CLASSIFICATION AND NOMENCLATURE OF TUMOURS OF THE SOFT (MESENCHYMAL) TISSUES I. TUMOURS OF FIBROUS TISSUE C. RHABDOMYOMA A. FIBROMA D. RHABDOMYOSARCOMA 1. Fibroma durum IV. TUMOURS OF BLOOD AND 2. Fibroma molle LYMPH VESSELS 3. Myxoma (myxofibroma) A. CAVERNOUS HAEMANGIOMA B. FIBROSARCOMA B. MALIGNANT HAEMANGIOENDOTHELIOMA (ANGIO- 1. Fibrosarcoma SARCOMA) 2. " Canine haemangiopericytoma" C. GLOMUS TUMOUR C. OTHER SARCOMAS D. LYMPHANGIOMA D. EQUINE SARCOID E. LYMPHANGIOSARCOMA (MALIGNANT LYMPH- E. TUMOUR-LIKE LESIONS ANGIOMA) 1. Cutaneous fibrous polyp F. TUMOUR-LIKE LESIONS 2. Keloid and hyperplastic scar V. MESENCHYMAL TUMOURS OF 3. Calcinosis circumscripta PERIPHERAL NERVES II. TUMOURS OF FAT TISSUE VI. -

Kaposiform Hemangioendothelioma in Tonsil of a Child

Rekhi et al. World Journal of Surgical Oncology 2011, 9:57 http://www.wjso.com/content/9/1/57 WORLD JOURNAL OF SURGICAL ONCOLOGY CASEREPORT Open Access Kaposiform hemangioendothelioma in tonsil of a child associated with cervical lymphangioma: a rare case report Bharat Rekhi1*, Shweta Sethi1, Suyash S Kulkarni2 and Nirmala A Jambhekar1 Abstract Kaposiform hemangioendothelioma (KHE) is an uncommon vascular tumor of intermediate malignant potential, usually occurs in the extremities and retroperitoneum of infants and is characterized by its association with lymphangiomatosis and Kasabach-Merritt phenomenenon (KMP) in certain cases. It has rarely been observed in the head and neck region and at times, can present without KMP. Herein, we present an extremely uncommon case of KHE occurring in tonsil of a child, associated with a neck swelling, but unassociated with KMP. A 2-year-old male child referred to us with history of sore throat, dyspnoea and right-sided neck swelling off and on, since birth, was clinicoradiologically diagnosed with recurrent tonsillitis, including right sided peritonsillar abscess, for which he underwent right-sided tonsillectomy, elsewhere. Histopathological sections from the excised tonsillar mass were reviewed and showed a tumor composed of irregular, infiltrating lobules of spindle cells arranged in kaposiform architecture with slit-like, crescentic vessels. The cells displayed focal lumen formation containing red blood cells (RBCs), along with platelet thrombi and eosinophilic hyaline bodies. In addition, there were discrete foci of several dilated lymphatic vessels containing lymph and lymphocytes. On immunohistochemistry (IHC), spindle cells were diffusely positive for CD34, focally for CD31 and smooth muscle actin (SMA), the latter marker was mostly expressed around the blood vessels. -

Benign Lymphangioendothelioma Manifested Clinically As Actinic Keratosis James A

Benign Lymphangioendothelioma Manifested Clinically as Actinic Keratosis James A. Yiannias, MD, Scottsdale, Arizona R.K. Winkelmann, MD, PhD, Scottsdale, Arizona Benign lymphangioendothelioma is an acquired lymphangiectatic lesion that must be recognized and differentiated from angiosarcoma, early Kaposi’s sarcoma, and lymphangioma circum- scriptum. We report the case of a 68-year-old woman with the clinical presentation of a possible actinic keratosis and the typical histologic findings of benign lymphangioendothelioma and an overly- ing actinic keratosis. enign lymphangioendothelioma is a recently de- scribed acquired lymphangiectatic lesion. Clin- ically, it usually appears as a dull pink to red- B 1 dish brown macule or plaque. We report a case in which the clinical presentation was possible actinic FIGURE 1. Benign lymphangioendothelioma at extensor keratosis, with typical histologic findings of benign forearm after punch biopsy. lymphangioendothelioma and an overlying pig- mented actinic keratosis. Recognition of this entity is vital because the histologic differential diagnosis cally, a pigmented actinic keratosis or lentigo was sus- includes angiosarcoma, early Kaposi’s sarcoma, and pected. A punch biopsy specimen showed delicate, lymphangioma circumscriptum. thin-walled, endothelium-lined spaces and clefts in the upper dermis, with an overlying pigmented Case Report actinic keratosis (Figure 2). These vascular channels A 68-year-old white woman in generally good health ran parallel to the epidermis and contained no or few presented with a small, light brown patch on the erythrocytes in their lumina. The endothelial cells extensor surface of her right forearm that grew radi- outlined collagen bundles. Furthermore, there was no ally over a 2-year period. The lesion was asymptom- erythrocyte extravasation, hemosiderin deposition, or atic, but the patient was concerned about cosmesis significant inflammation, and no abnormal muscular and requested that it be removed. -

Cervical Lymphangioma in Adult Cervical Lymphangioma in Adult

AIJOC 10.5005/jp-journals-10003-1101 CASE REPORT Cervical Lymphangioma in Adult Cervical Lymphangioma in Adult Vinod Tukaram Kandakure, Girish Vitthalrao Thakur, Amit Ramesh Thote, Ayesha Junaid Kausar ABSTRACT There was no enhancing portion, and the lesion measured Lymphangiomas are uncommon congenital lesions of the approximately 6 × 4 × 3 cm. It was profoundly hyperintense lymphatic system which are usually present in childhood. We on T2W1 images (Fig. 2). It showed multiple incomplete report a case of adult lymphangioma, localized in the neck, and thin septi with communicating loculi. discuss the presentation, diagnosis and management of this tumor. Surgery Keywords: Head and neck, Lymphangioma, Children, Diagnosis, Treatment. The mass was reached through a 7 cm transverse skin incision in the submandibular region. Cystic mass was seen in How to cite this article: Kandakure VT, Thakur GV, Thote AR, Kausar AJ. Cervical Lymphangioma in Adult. Int J subcutaneous plane. Mass was dissected from tail of parotid Otorhinolaryngol Clin 2012;4(3):147-150. laterally then from behind posterior belly of digastric muscle till submandibular gland medially to vallecula in Source of support: Nil superomedial plane. It was touching internal jugular vein Conflict of interest: None declared (IJV) and common carotid artery posteriorly. Cystic mass was draining into the IJV via small vessel (Fig. 3). That vessel INTRODUCTION was ligated near the IJV. Although the lesion was in close Lymphangioma is an uncommon benign pathology, usually proximity to nerves, vessels and muscles, there was no reported in children and rarely in adults. Cervical lymphangioma involves congenital and cystic abnormalities derived from lymphatic vessels with a progressive and painless growth. -

Coexistence of Lymphangioma Circumscriptum and Angiokeratoma

C logy ase to R a e m p r o e Kemeriz et al., Dermatol Case Rep 2019, 4:2 r t D Dermatology Case Reports Case Report Open Access Coexistence of Lymphangioma Circumscriptum and Angiokeratoma in the Same Area: A Case Report Funda Kemeriz1*, Muzeyyen Gonul2, Aysun Gokce3 and Murat Alper3 1Department of Dermatology, Aksaray University, Aksaray, Turkey 2Department of Dermatology, Dıskapı Research and Training Hospital, Ankara, Turkey 3Department of Pathology, Dıskapı Research and Training Hospital, Ankara, Turkey *Corresponding author: Funda Kemeriz, Department of Dermatology, Aksaray University, Faculty of Medicine, Aksaray, Turkey, Tel: +905377104130; E-mail: [email protected] Received date: May 24, 2019; Accepted date: May 31, 2019; Published date: June 10, 2019 Copyright: ©2019 Kemeriz F, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. Abstract Lymphangioma is a rare benign malformation of lymphatic vessels. Lymphangioma Circumscriptum (LC) is the most common type. Angiokeratoma is a vascular lesion which is considered to be caused primarily by vascular ectasia in the papillary dermis and epidermal changes developing secondarily. Here we presented a 51-year-old patient developing angiokeratoma and LC in the same area with literature’s data. Previously, one case pointing out to the coexistence of LC and angiokeratoma in cutaneous tissue has been reported in the literature. In our case, the lesions’ general clinical appearance was consistent with angiokeratoma and dermoscopic examination revealed the findings of angiokeratoma in some areas, histopathologically one of the patients’ biopsies specimens revealed angiokeratoma, the other was consistent with lymphangioma. -

Role of Prenatal Imaging in the Diagnosis and Management of Fetal

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Role of prenatal imaging in the diagnosis and management of fetal facio‑cervical masses Weizeng Zheng1,5, Shuangshuang Gai2,5, Jiale Qin2, Fei Qiu3, Baohua Li4 & Yu Zou1* Congenital facio‑cervical masses can be a developmental anomaly of cystic, solid, or vascular origin, and have an inseparable relationship with adverse prognosis. This retrospective cross‑sectional study aimed at determining on the prenatal diagnosis of congenital facio‑cervical masses, its management and outcome in a large tertiary referral center. We collected information on prenatal clinical data, pregnancy outcomes, survival information, and fnal diagnosis. Out of 130 cases of facio‑cervical masses, a total of 119 cases of lymphatic malformations (LMs), 2 cases of teratoma, 2 cases of thyroglossal duct cyst, 4 cases of hemangioma, 1 case of congenital epulis, and 2 cases of dermoid cyst were reviewed. The accuracy of prenatal ultrasound was 93.85% (122/130). Observations of diameters using prenatal ultrasound revealed that the bigger the initial diameter is, the bigger the relative change during pregnancy. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed that 2 cases of masses were associated with airway compression. In conclusion, ultrasound has a high overall diagnostic accuracy of fetal face and neck deformities. Prenatal US can enhance the management of ambulatory monitoring and classifcation. Furthermore, MRI provided a detailed assessment of fetal congenital malformations, as well as visualization of the trachea, presenting a multi‑dimensional anatomical relationship. Facio-cervical masses are frequent clinical fndings in the pediatric population with only 55% of these lesions being congenital1. In fetuses, the common lesions include lymphatic malformations (LMs), dermoid cysts, cervi- cal teratoma, thyroglossal duct cysts, hemangioma, goiter, and branchial cyst 2–4. -

Lymphangioma in Patients with Pulmonary

cer Scien an ce C & f o T l h Radzikowska et al., J Cancer Sci Ther 2016, 8:9 a e n r a Journal of r p u y o DOI: 10.4172/1948-5956.1000419 J ISSN: 1948-5956 Cancer Science & Therapy Research Article Open Access Lymphangioma in Patients with Pulmonary Lymphangioleiomyomatosis: Results of Sirolimus Treatment Elżbieta Radzikowska1*, Katarzyna Błasińska-Przerwa2, Paulina Skrońska3, Elżbieta Wiatr1, Tomasz Świtaj4, Agnieszka Skoczylas5 and Kazimierz Roszkowski-Śliż1 1Department of Lung Diseases, National Tuberculosis and Lung Diseases Research Institute, Warsaw, Poland 2Department of Radiology, National Tuberculosis and Lung Diseases Research Institute, Warsaw, Poland 3Department of Genetics and Clinical Immunology, National Tuberculosis and Lung Diseases Research Institute, Warsaw, Poland 4Department of Soft Tissue/Bone Sarcoma and Melanoma, Maria Skłodowska-Curie Memorial Cancer Centre and Institute of Oncology, Warsaw, Poland 5Department of Geriatrics, National Institute of Geriatrics, Rheumatology and Rehabilitation, Warsaw, Poland Abstract Objective: Lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM) is a rare disease caused by abnormal proliferation of smooth muscle-like cells mainly in lungs and axial lymph nodes, that belongs to the group of PEComa tumours. Chylous pleural and abdominal effusions, lymhangioleiomiomas, angiomyolipomas are noticed in disease course. Sirolimus has been approved for LAM treatment, and also it has been reported to decrease the size of angiomyolipomas, lymphangiooedma, pleural and peritoneal chylous effusion. The aim of the study was to assess the significance of sirolimus therapy in patients with LAM and lymphangioma in retroperitoneal space. Method: Fourteen women with confirmed diagnosis of LAM (13 with sporadic LAM, and one TSC/LAM) and presence of lymphangioma in abdominal cavity were retrospectively reviewed. -

Acquired Progressive Lymphangioma in the Inguinal Area Mimicking Giant Condyloma Acuminatum

Acquired Progressive Lymphangioma in the Inguinal Area Mimicking Giant Condyloma Acuminatum Jian-Wei Zhu, MD, PhD; Zhong-Fa Lu, MD, PhD; Min Zheng, MD, PhD Practice Points Acquired progressive lymphangioma in the genital area is easily misdiagnosed and therefore requires careful examination. Wide excision of acquired progressive lymphangioma is suggested to prevent recurrence. Lymphangioma is a benign proliferation of the communicate with the peripheral draining channels.1 lymphatic vessels that accounts for approximately Based on the clinical and pathologic characteristics, 4% of vascular malformations and 26% of benign lymphangiomas are broadly classified as superficial vascular tumors. ComparedCUTIS to those arising in (lymphangioma circumscriptum) or deep (cavern- nongenital areas, lymphangiomas of the vulva and ous lymphangioma).2 There is no clear distinction genital areas are more hyperplastic, possibly due between these 2 classifications, but the sole differ- to the loose connective tissue, which can cause ence appears to be the extent of the malformation.3 a cauliflowerlike appearance and may easily be Lymphangiomas also may be classified as simple, cav- misdiagnosed as genital warts or molluscum ernous, or cystic according to the size of the vessels. contagiosum. We report a case of acquired pro- Congenital and acquired lymphangiomas also gressiveDo lymphangioma (APL) Not of the inguinal area may beCopy differentiated by cutaneous localization. that mimicked giant condyloma acuminatum and Congenital lymphangiomas result from a hamar- showed favorable results following surgical exci- tomatous malformation of lymphatic vessels, while sion. We also provide a review of the literature acquired lymphangiomas are the result of acquired regarding the pathogenesis, diagnosis, differen- obstruction of lymphatic vessels induced by surgery, tial diagnosis, and treatment of APL. -

Lymphangioma Circumscriptum of the Vulva in a Patient with Noonan Syndrome

Lymphangioma Circumscriptum of the Vulva in a Patient With Noonan Syndrome Llana Pootrakul, MD, PhD; Michael R. Nazareth, MD, PhD; Richard T. Cheney, MD; Marcelle A. Grassi, MD Practice Points Lymphatic malformations such as lymphedema and cystic hygroma are not uncommonly observed in patients with Noonan syndrome; there are rare reports of cutaneous lymphangioma in this population. Lymphangioma circumscriptum of the vulva should be considered when patients with Noonan syndrome present with grouped vesicular lesions in the vulvar region characterized by erythema, swelling, and/or drainage. The mainstay of treatment of lymphangioma circumscriptum of the vulva includes complete surgical resection of superficial CUTISlesions and deep communicating lymphatics. Lymphangioma circumscriptum (LC) results from he clinical manifestations of Noonan syn- the development of abnormal lymphatic vas- drome (NS) are seen in multiple organ culature and is characterized by the presence Tsystems and include cardiovascular, muscu- of grouped vesicles filled with clear or colored loskeletal, genitourinary, dermatologic, and gastro- fluid. Vulvar localization is uncommon. Abnor- intestinal findings. Patients with NS may present malitiesDo of the lymphatic system,Not such as lymph- with a wideCopy range of features including ptosis of the edema and cystic hygroma, are well-known eyelids, ocular hypertelorism, epicanthus, pterygium features of genetic disorders such as Noonan syn- colli, undescended testicles in men, short stature, drome (NS) and Turner syndrome. We report the pectus excavatum or pectus carinatum, congenital case of a patient with NS who presented with heart defects, cubitus valgus, low-set ears, mental LC of the vulva. We also discuss the expanding retardation, micrognathia, lymphedema, and cystic spectrum of clinical anomalies associated with hygroma.1,2 Lymphatic dysplasia has been reported in the presentation of NS.