The-Captains-Daughter.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Musorgsky's Boris Godunov

22 JANUARY 2019 Musorgsky’s Boris Godunov PROFESSOR MARINA FROLOVA-WALKER Today we are going to look at what is possibly the most famous of Russian operas – Musorgsky’s Boris Godunov. Its route to international celebrity is very clear – the great impresario Serge Diaghilev staged it in Paris in 1908, with the star bass Fyodor Chaliapin in the main role. The opera the Parisians saw would have taken Musorgsky by surprise. First, it was staged in a heavily reworked edition made by Rimsky-Korsakov after Musorgsky’s death, where only about 20% of the bars in the original were left unchanged. But that was still a modest affair compared to the steps Diaghilev took on his own initiative. The production had a Russian cast singing the opera in Russian, and Diaghilev was worried that the Parisians would lose patience with scenes that were more wordy, since they would follow none of it, so he decided simply to cut these scenes, even though this meant that some crucial turning points in the drama were lost altogether. He then reordered the remaining scenes to heighten contrasts, jumbling the chronology. In effect, the opera had become a series of striking tableaux rather than a drama with a coherent plot. But as pure spectacle, it was indeed impressive, with astonishing sets provided by the painter Golovin and with the excitement generated by Chaliapin as Boris. For all its shortcomings, it was this production that brought Musorgsky’s masterwork to the world’s attention. 1908, the year of the Paris production was nearly thirty years after Musorgsky’s death, and nearly and forty years after the opera was completed. -

The Transformation of Pushkin's Eugene Onegin Into Tchaikovsky's Opera

THE TRANSFORMATION OF PUSHKIN'S EUGENE ONEGIN INTO TCHAIKOVSKY'S OPERA Molly C. Doran A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC August 2012 Committee: Eftychia Papanikolaou, Advisor Megan Rancier © 2012 Molly Doran All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Eftychia Papanikolaou, Advisor Since receiving its first performance in 1879, Pyotr Il’yich Tchaikovsky’s fifth opera, Eugene Onegin (1877-1878), has garnered much attention from both music scholars and prominent figures in Russian literature. Despite its largely enthusiastic reception in musical circles, it almost immediately became the target of negative criticism by Russian authors who viewed the opera as a trivial and overly romanticized embarrassment to Pushkin’s novel. Criticism of the opera often revolves around the fact that the novel’s most significant feature—its self-conscious narrator—does not exist in the opera, thus completely changing one of the story’s defining attributes. Scholarship in defense of the opera began to appear in abundance during the 1990s with the work of Alexander Poznansky, Caryl Emerson, Byron Nelson, and Richard Taruskin. These authors have all sought to demonstrate that the opera stands as more than a work of overly personalized emotionalism. In my thesis I review the relationship between the novel and the opera in greater depth by explaining what distinguishes the two works from each other, but also by looking further into the argument that Tchaikovsky’s music represents the novel well by cleverly incorporating ironic elements as a means of capturing the literary narrator’s sardonic voice. -

A Study of Nabokov's Commentary on Pushkin's Eugene Onegin: the First Half of Chapter II

On Chapter Two: I-XVII Shoko Miura To study Vladimir Nabokov's Commentary to Eugene Onegin is to discover with what remarkable energy and meticulous research Nabokov enables us to relive Pushkin's writing of the poem. It is the method Nabokov uses in his lectures as well. He follows the story of the poet's experiences day by day, his readings, his correspondences, his creations of poems and prose, the frustrations with the authorities, the various emotions that went through Pushkin's heart, in order to revive the genius that made Eugene Onegin. Only, because of the form of the Commentary, the story is broken into separate and scattered annotations. While it will take more than this brief study to piece together the entire story, reading and researching only a few pages of the Commentary enables us to see what Nabokov was trying to accomplish. It was my task to cover the first half of Chapter II (Stanzas 1–17, Commentary 217-266) in which nothing very dramatic happens, but which establishes the fundamental stage upon which the love story and the tragedy will later occur. Chapter II begins with the pastoral theme in the first five stanzas. It dwells on Onegin’s uneventful daily management of his land, the beauty of the countryside and, naturally, his boredom. The appearance of Lenski then introduces the theme of friendship which develops between him and Onegin. Pushkin stayed in Odessa the entire time that he was writing the stanzas 1 to 17, so that there is a slow and controlled plot development and a unified pace in the flow of narrative. -

The Superfluous Man in Nineteenth-Century Russian Literature

Hamren 1 The Eternal Stranger: The Superfluous Man in Nineteenth-Century Russian Literature A Thesis Submitted to The Faculty of the School of Communication In Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Arts in English By Kelly Hamren 4 May 2011 Hamren 2 Liberty University School of Communication Master of Arts in English Dr. Carl Curtis ____________________________________________________________________ Thesis Chair Date Dr. Emily Heady ____________________________________________________________________ First Reader Date Dr. Thomas Metallo ____________________________________________________________________ Second Reader Date Hamren 3 Acknowledgements I would like to thank those who have seen me through this project and, through support for my academic endeavors, have made it possible for me to come this far: to Dr. Carl Curtis, for his insight into Russian literature in general and Dostoevsky in particular; to Dr. Emily Heady, for always pushing me to think more deeply about things than I ever thought I could; to Dr. Thomas Metallo, for his enthusiastic support and wisdom in sharing scholarly resources; to my husband Jarl, for endless patience and sacrifices through two long years of graduate school; to the family and friends who never stopped encouraging me to persevere—David and Kathy Hicks, Karrie Faidley, Jennifer Hughes, Jessica Shallenberger, and Ramona Myers. Hamren 4 Table of Contents: Chapter 1: Introduction………………………………………………………………………...….5 Chapter 2: Epiphany and Alienation...................................……………………………………...26 Chapter 3: “Yes—Feeling Early Cooled within Him”……………………………..……………42 Chapter 4: A Soul not Dead but Dying…………………………………………………………..67 Chapter 5: Where There’s a Will………………………………………………………………...96 Chapter 6: Conclusion…………………………………………………………………………..130 Works Cited…………………………………………………………………………………….134 Hamren 5 Introduction The superfluous man is one of the most important developments in the Golden Age of Russian literature—the period beginning in the 1820s and climaxing in the great novels of Dostoevsky and Tolstoy. -

Boris Godunov

Boris Godunov and Little Tragedies Alexander Pushkin Translated by Roger Clarke FE<NFIC; :C8JJ@:J ONEWORLD CLASSICS LTD London House 243-253 Lower Mortlake Road Richmond Surrey TW9 2LL United Kingdom www.oneworldclassics.com Boris Godunov first published in Russian in 1831 The Mean-Spirited Knight first published in Russian in 1836 Mozart and Salieri first published in Russian in 1831 The Stone Guest first published in Russian in 1839 A Feast during the Plague first published in Russian in 1832 This translation first published by Oneworld Classics Limited in 2010 English translations, introductions, notes, extra material and appendices © Roger Clarke, 2010 Front cover image © Catriona Gray Printed in Great Britain by MPG Books, Cornwall ISBN: 978-1-84749-147-3 All the material in this volume is reprinted with permission or presumed to be in the public domain. Every effort has been made to ascertain and acknowledge the copyright status, but should there have been any unwitting oversight on our part, we would be happy to rectify the error in subsequent printings. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not be resold, lent, hired out or otherwise circulated without the express prior consent of the publisher. Contents Boris Godunov 1 Introduction by Roger Clarke 3 Boris Godunov 9 Little Tragedies 105 Introduction by Roger Clarke 107 The Mean-Spirited Knight 109 Mozart and Salieri 131 The Stone Guest 143 A Feast during the Plague 181 Notes on Boris Godunov 193 Notes on Little Tragedies 224 Extra Material 241 Alexander Pushkin’s Life 243 Boris Godunov 251 Little Tragedies 262 Translator’s Note 280 Select Bibliography 282 Appendices 285 1. -

The Inextricable Link Between Literature and Music in 19Th

COMPOSERS AS STORYTELLERS: THE INEXTRICABLE LINK BETWEEN LITERATURE AND MUSIC IN 19TH CENTURY RUSSIA A Thesis Presented to The Graduate Faculty of The University of Akron In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Music Ashley Shank December 2010 COMPOSERS AS STORYTELLERS: THE INEXTRICABLE LINK BETWEEN LITERATURE AND MUSIC IN 19TH CENTURY RUSSIA Ashley Shank Thesis Approved: Accepted: _______________________________ _______________________________ Advisor Interim Dean of the College Dr. Brooks Toliver Dr. Dudley Turner _______________________________ _______________________________ Faculty Reader Dean of the Graduate School Mr. George Pope Dr. George R. Newkome _______________________________ _______________________________ School Director Date Dr. William Guegold ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page CHAPTER I. OVERVIEW OF THE DEVELOPMENT OF SECULAR ART MUSIC IN RUSSIA……..………………………………………………..……………….1 Introduction……………………..…………………………………………………1 The Introduction of Secular High Art………………………………………..……3 Nicholas I and the Rise of the Noble Dilettantes…………………..………….....10 The Rise of the Russian School and Musical Professionalism……..……………19 Nationalism…………………………..………………………………………..…23 Arts Policies and Censorship………………………..…………………………...25 II. MUSIC AND LITERATURE AS A CULTURAL DUET………………..…32 Cross-Pollination……………………………………………………………...…32 The Russian Soul in Literature and Music………………..……………………...38 Music in Poetry: Sound and Form…………………………..……………...……44 III. STORIES IN MUSIC…………………………………………………… ….51 iii Opera……………………………………………………………………………..57 -

Russia in the Accounts of Sixteenth-Century English Voyagers, Ed

Rude and Barbarous Kingdom: Russia in the Accounts of Sixteenth-Century English Voyagers, ed. Lloyd E. Berry and Robert O. Crummey, Madison, Milwaukee and London: University of Wisconsin Press, 1968. xxiii, 391 pp. $7.50. This attractively-presented volume is yet another instance of the work of publishers in making available in a more accessible form primary sources which it was hitherto necessary to seek among dusty collections of the Hakluyt Society publications. Here we have in a single volume accounts of the travels of Richard Chancellor, Anthony Jenkinson and Thomas Randolph, together with the better-known and more extensive narrative contained in Giles Fletcher's Of the Russe Commonwealth and Sir Jerome Horsey's Travels. The most entertaining component of this volume is certainly the series of descriptions culled from George Turberville's Tragicall Tales, all written to various friends in rhyming couplets. This was apparently the sixteenth-century equivalent of the picture postcard, through apparently Turberville was not having a wonderful time! English merchants evidently enjoyed high favour at the court of Ivan IV, but Horsey's account reflects the change of policy brought about by the accession to power of Boris Godunov. Although the English travellers were very astute observers, naturally there are many inaccuracies in their accounts. Horsey, for instance, mistook the Volkhov for the Volga, and most of these good Anglicans came away from Russia with weird ideas about the Orthodox Church. The editors have, by their introductions and footnotes, provided an invaluable service. However, in the introduction to the text of Chancellor's account it is stated that his observation of the practice of debt-bondage is interesting in that "the practice of bondage by loan contract did not reach its full development until the economic collapse at the end of the century and the civil wars that followed". -

The End of Boris. Contribution to an Aesthetics of Disorientation

The end of Boris. ConTriBuTion To an aesTheTiCs of disorienTaTion by reuven Tsur The Emergence of the Opera–An Outline Boris Godunov was tsar of russia in the years 1598–1605. he came to power after fyodor, the son of ivan the terrible, died without heirs. Boris was fyodor's brother-in-law, and in fact, even during fyodor's life he was the omnipotent ruler of russia. ivan the Terrible had had his eldest son executed, whereas his youngest son, dmitri, had been murdered in unclear circumstances. in the 16–17th centuries, as well as among the 19th-century authors the prevalent view was that it was Boris who ordered dmitri's murder (some present-day historians believe that dmitri's murder too was ordered by ivan the Terrible). in time, two pretenders appeared, one after the other, who claimed the throne, purporting to be dmitri, saved miraculously. Boris' story got told in many versions, in history books and on the stage. Most recently, on 12 July 2005 The New York Times reported the 295-year-late premiere of the opera Boris Goudenow, or The Throne Attained Through Cunning, or Honor Joined Happily With Affection by the German Baroque composer Johann Mattheson. Boris' story prevailed in three genres: history, tragedy, and opera. in the nineteenth century, the three genres culminated in n. M. Karamzin's monumental History of the Russian State, in alexander Pushkin's tragedy Boris Godunov, and in Modest Mussorgsky's opera Boris Godunov. each later author in this list liberally drew upon his predecessors. in her erudite and brilliant 397 reuven tsur the end of boris book, Caryl emerson (1986) compared these three versions in a Pimen interprets as an expression of the latter's ambition. -

Folklore and the Construction of National Identity in Nineteenth Century Russian Literature

Folklore and the Construction of National Identity in Nineteenth Century Russian Literature Jessika Aguilar Submitted in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Columbia University 2016 © 2016 Jessika Aguilar All rights reserved Table of Contents 1. Introduction……………………………………………………………………………..…..1 2. Alexander Pushkin: Folklore without the Folk……………………………….20 3. Nikolai Gogol: Folklore and the Fragmentation of Authorship……….54 4. Vladimir Dahl: The Folk Speak………………………………………………..........84 5. Conclusion……………………………………………………………………………........116 6. Bibliography………………………………………………………………………………122 i Introduction In his “Literary Reveries” of 1834 Vissarion Belinsky proclaimed, “we have no literature” (Belinskii PSS I:22). Belinsky was in good company with his assessment. Such sentiments are rife in the critical essays and articles of the first third of the nineteenth century. A decade earlier, Aleksandr Bestuzhev had declared that, “we have a criticism but no literature” (Leighton, Romantic Criticism 67). Several years before that, Pyotr Vyazemsky voiced a similar opinion in his article on Pushkin’s Captive of the Caucasus : “A Russian language exists, but a literature, the worthy expression of a mighty and virile people, does not yet exist!” (Leighton, Romantic Criticism 48). These histrionic claims are evidence of Russian intellectuals’ growing apprehension that there was nothing Russian about the literature produced in Russia. There was a prevailing belief that -

Boris Godunov

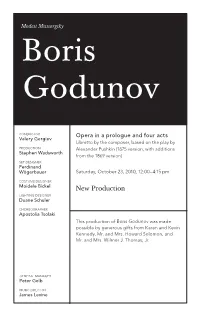

Modest Mussorgsky Boris Godunov CONDUCTOR Opera in a prologue and four acts Valery Gergiev Libretto by the composer, based on the play by PRODUCTION Alexander Pushkin (1875 version, with additions Stephen Wadsworth from the 1869 version) SET DESIGNER Ferdinand Wögerbauer Saturday, October 23, 2010, 12:00–4:15 pm COSTUME DESIGNER Moidele Bickel New Production LIGHTING DESIGNER Duane Schuler CHOREOGRAPHER Apostolia Tsolaki This production of Boris Godunov was made possible by generous gifts from Karen and Kevin Kennedy, Mr. and Mrs. Howard Solomon, and Mr. and Mrs. Wilmer J. Thomas, Jr. GENERAL MANAGER Peter Gelb MUSIC DIRECTOR James Levine 2010–11 Season The 268th Metropolitan Opera performance of Modest Mussorgsky’s Boris Godunov Conductor Valery Gergiev in o r d e r o f v o c a l a p p e a r a n c e Nikitich, a police officer Xenia, daughter of Boris Valerian Ruminski Jennifer Zetlan Mitiukha, a peasant Feodor, son of Boris Mikhail Svetlov Jonathan A. Makepeace Shchelkalov, a boyar Nurse, nanny to Boris’s Alexey Markov children Larisa Shevchenko Prince Shuisky, a boyar Oleg Balashov Boyar in Attendance Brian Frutiger Boris Godunov René Pape Marina Ekaterina Semenchuk Pimen, a monk Mikhail Petrenko Rangoni, a Jesuit priest Evgeny Nikitin Grigory, a monk, later pretender to the Russian throne Holy Fool Aleksandrs Antonenko Andrey Popov Hostess of the Inn Chernikovsky, a Jesuit Olga Savova Mark Schowalter Missail Lavitsky, a Jesuit Nikolai Gassiev Andrew Oakden Varlaam Khrushchov, a boyar Vladimir Ognovenko Dennis Petersen Police Officer Gennady Bezzubenkov Saturday, October 23, 2010, 12:00–4:15 pm This afternoon’s performance is being transmitted live in high definition to movie theaters worldwide. -

Freedom from Violence and Lies Essays on Russian Poetry and Music by Simon Karlinsky

Freedom From Violence and lies essays on russian Poetry and music by simon Karlinsky simon Karlinsky, early 1970s Photograph by Joseph Zimbrolt Ars Rossica Series Editor — David M. Bethea (University of Wisconsin-Madison) Freedom From Violence and lies essays on russian Poetry and music by simon Karlinsky edited by robert P. Hughes, Thomas a. Koster, richard Taruskin Boston 2013 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data: A catalog record for this book as available from the Library of Congress. Copyright © 2013 Academic Studies Press All rights reserved ISBN 978-1-61811-158-6 On the cover: Heinrich Campendonk (1889–1957), Bayerische Landschaft mit Fuhrwerk (ca. 1918). Oil on panel. In Simon Karlinsky’s collection, 1946–2009. © 2012 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn Published by Academic Studies Press in 2013. 28 Montfern Avenue Brighton, MA 02135, USA [email protected] www.academicstudiespress.com Effective December 12th, 2017, this book will be subject to a CC-BY-NC license. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/. Other than as provided by these licenses, no part of this book may be reproduced, transmitted, or displayed by any electronic or mechanical means without permission from the publisher or as permitted by law. The open access publication of this volume is made possible by: This open access publication is part of a project supported by The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Humanities Open Book initiative, which includes the open access release of several Academic Studies Press volumes. To view more titles available as free ebooks and to learn more about this project, please visit borderlinesfoundation.org/open. -

From Onegin to Ada: Nabokov's Canon and the Texture of Time Marijeta Bozovic Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requireme

From Onegin to Ada: Nabokov’s Canon and the Texture of Time Marijeta Bozovic Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2011 2011 Marijeta Bozovic all rights reserved ABSTRACT From Onegin to Ada: Nabokov’s Canon and the Texture of Time Marijeta Bozovic The library of existing scholarship on Vladimir Nabokov circles uncomfortably around his annotated translation Eugene Onegin (1964) and late English-language novel Ada, or Ardor (1969). This dissertation juxtaposes Pushkin’s Evgenii Onegin (1825-32) with Nabokov’s two most controversial monuments and investigates Nabokov’s ambitions to enter a canon of Western masterpieces, re-imagined with Russian literature as a central strain. I interrogate the implied trajectory for Russian belles lettres, culminating unexpectedly in a novel written in English and after fifty years of emigration. My subject is Nabokov, but I use this hermetic author to raise broader questions of cultural borrowing, transnational literatures, and struggles with rival canons and media. Chapter One examines Pushkin’s Evgenii Onegin, the foundation stone of the Russian canon and a meta-literary fable. Untimely characters pursue one another and the latest Paris and London fashions in a text that performs and portrays anxieties of cultural borrowing and Russia’s position vis-à-vis the West. Fears of marginalization are often expressed in terms of time: I use Pascale Casanova’s World Republic of Letters to suggest a global context for the “belated” provinces and fashion-setting centers of cultural capital. Chapter Two argues that Nabokov’s Eugene Onegin, three-quarters provocation to one-quarter translation, focuses on the Russian poet and his European sources.