Sir Charles Napier by T.R.E. Holmes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Burkeian Analysis of the Crimean War Speeches of John Bright

/, 7 A BURKEIAN ANALYSIS OF THE CRIMEAN WAR SPEECHES OF JOHN BRIGHT THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE By Jeff Davis Bass, B.A. Denton, Texas August, 1974 Bass, Jeff, A Rrkeian Aralysis of the Crime War abecs of J ohn Bright. Master of Science (Speech Communi- cation and Drama), August, 1974, 134 pp., bibliography, 31 titles. This study investigates the motives behind the rhetorical strategies of rejection and acceptance used by John Bright in his four Parliamentary speeches opposing the Crimean War. Kenneth Burke's dramatistic pentad was used to evaluate the four speeches. An examination of the pentad's five elements reveals that Bright had six motives for opposing the war. To achieve his purpose in giving the speeches--to restore peace to England and the world--Bright' used the major rhetorical agencies of rejection and acceptance. Bright's act, his selection of agencies, and his purpose were all definitely influenced by the scene in which they occurred. TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page I. INTRODUCTION . , , , , .. , , , . , , *, , , , 3 Purpose Speeches to be Analyzed Method of Analysis The Dramatistic Pentad The Burkeian Approach and the Rhetorical Critic Summaryof Design II, ANALYSIS OF THE SCENE.. .00.00,. .,,,0,9,0 20 The Scenic Circumference in Europe The Scenic Circumference in England The Tmmediate Scenic Circumference . , . , , , , 49 III, ACT, AGENT, AND RATIO ANALYSIS 4 John Bright, the Agent Ratio Analysis Act-Agent Ratio Scene-Act Ratio IV, AGENCY, PURPOSE, AND RATIO ANALYSIS, . * , , * 88 Purpose Ratio Analysis Purpose-Scene Ratio Agency-Scene Ratio Agent-Agency Ratio V. -

The Ionian Islands in British Official Discourses; 1815-1864

1 Constructing Ionian Identities: The Ionian Islands in British Official Discourses; 1815-1864 Maria Paschalidi Department of History University College London A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy to University College London 2009 2 I, Maria Paschalidi, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. 3 Abstract Utilising material such as colonial correspondence, private papers, parliamentary debates and the press, this thesis examines how the Ionian Islands were defined by British politicians and how this influenced various forms of rule in the Islands between 1815 and 1864. It explores the articulation of particular forms of colonial subjectivities for the Ionian people by colonial governors and officials. This is set in the context of political reforms that occurred in Britain and the Empire during the first half of the nineteenth-century, especially in the white settler colonies, such as Canada and Australia. It reveals how British understandings of Ionian peoples led to complex negotiations of otherness, informing the development of varieties of colonial rule. Britain suggested a variety of forms of government for the Ionians ranging from authoritarian (during the governorships of T. Maitland, H. Douglas, H. Ward, J. Young, H. Storks) to representative (under Lord Nugent, and Lord Seaton), to responsible government (under W. Gladstone’s tenure in office). All these attempted solutions (over fifty years) failed to make the Ionian Islands governable for Britain. The Ionian Protectorate was a failed colonial experiment in Europe, highlighting the difficulties of governing white, Christian Europeans within a colonial framework. -

Historical Records of the 79Th Cameron Highlanders

%. Z-. W ^ 1 "V X*"* t-' HISTORICAL RECORDS OF THE 79-m QUEEN'S OWN CAMERON HIGHLANDERS antr (Kiritsft 1m CAPTAIN T. A. MACKENZIE, LIEUTENANT AND ADJUTANT J. S. EWART, AND LIEUTENANT C. FINDLAY, FROM THE ORDERLY ROOM RECORDS. HAMILTON, ADAMS & Co., 32 PATERNOSTER Row. JDebonport \ A. H. 111 112 FOUE ,STRSET. SWISS, & ; 1887. Ms PRINTED AT THE " " BREMNER PRINTING WORKS, DEVOXPORT. HENRY MORSE STETHEMS ILLUSTRATIONS. THE PHOTOGRAVURES are by the London Typographic Etching Company, from Photographs and Engravings kindly lent by the Officers' and Sergeants' Messes and various Officers of the Regiment. The Photogravure of the Uniform Levee Dress, 1835, is from a Photograph of Lieutenant Lumsden, dressed in the uniform belonging to the late Major W. A. Riach. CONTENTS. PAGK PREFACE vii 1793 RAISING THE REGIMENT 1 1801 EGYPTIAN CAMPAIGN 16 1808 PENINSULAR CAMPAIGN .. 27 1815 WATERLOO CAMPAIGN .. 54 1840 GIBRALTAR 96 1848 CANADA 98 1854 CRIMEAN CAMPAIGN 103 1857 INDIAN MUTINY 128 1872 HOME 150 1879 GIBRALTAR ... ... .. ... 161 1882 EGYPTIAN CAMPAIGN 166 1884 NILE EXPEDITION ... .'. ... 181 1885 SOUDAN CAMPAIGN 183 SERVICES OF THE OFFICERS 203 SERVICES OF THE WARRANT OFFICERS ETC. .... 291 APPENDIX 307 LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS, SIR JOHN DOUGLAS Frontispiece REGIMENTAL COLOUR To face SIR NEIL DOUGLAS To face 56 LA BELLE ALLIANCE : WHERE THE REGIMENT BIVOUACKED AFTER THE BATTLE OF WATERLOO .. ,, 58 SIR RONALD FERGUSON ,, 86 ILLUSTRATION OF LEVEE DRESS ,, 94 SIR RICHARD TAYLOR ,, 130 COLOURS PRESENTED BY THE QUEEN ,, 152 GENERAL MILLER ,, 154 COLONEL CUMING ,, 160 COLONEL LEITH , 172 KOSHEH FORT ,, 186 REPRESENTATIVE GROUP OF CAMERON HIGHLANDERS 196 PREFACE. WANT has long been felt in the Regiment for some complete history of the 79th Cameron Highlanders down to the present time, and, at the request of Lieutenant-Colonel Everett, D-S.O., and the officers of the Regiment a committee, con- Lieutenant and sisting of Captain T. -

Sir Charles Napier

englt~fJ atlnl of Xlction SIR CHARLES NAPIER I\I.~~III SIR CHARLES NAPIER. SIR CHARLES NAPIER BY COLONEL SIR WILLIAM F.BUTLER 3ionbon MACMILLAN AND cn AND NEW YORK 1890 .AU rlgjts f'<8erved CONTENTS CHAPTER I PAOB THI HOME AT CELBRIDGE--FIRST COllMISSION CHAPTER II EARLY SEBVICE--THE PENINSULA. 14 CHAPTER III CoRUIIINA 27 CHAPTER IV THE PENINSULA IN 1810-11-BEIUIUDA-AMERICA -RoYAL MILITARY COLLEGE. 46 CHAPTER V CEPHALONIA 62 • CHAPTER VI OUT OF HARNESS 75 vi CONTENTS CHAPTER VII PAOK COlWA..'ID OJ' THE NORTHERN DISTRICT • 86 CHAPTER VIII bmIA-THE WAR IN Scn.""DE 98 CHAPTER IX . ~.17 CHAPTER X THE MORROW OJ' lliANEE-THE ACTION AT DUBBA 136 CHAPTER XI THE ADHINISTRATION OJ' ScnlDE • • 152 CHAPTER XII ENGLAND--1848 TO 1849 175 CHAPTER XIII ColDlANDER-IN-CHlEl!' IN INDIA 188 CHAPTER XIV HOKE-LAsT ILLNESS-DEATH THE HOldE AT CELBRIDGE-FIRST COMMISSION • TEN miles west of Dublin, on the north bank of the Liffey, stands a village of a single street, called Celbridge. In times so remote that their record only survives in a name, some Christian hermit built here himself a cell for house, church, and tomb; a human settlement took root around the spot; deer-tracks' widened into pathways; pathways broadened into roads; and at last a bridge spanned the neighbouring stream. The church and the bridge, two prominent land-marks on the road of civilisation, jointly named the place, and Kildrohid or "the church by the bridge" became hence forth a local habitation and a name, twelve hundred years later to be anglicised into. -

British Major-General Charles George Gordon and His Legacies, 1885-1960 Stephanie Laffer

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2010 Gordon's Ghosts: British Major-General Charles George Gordon and His Legacies, 1885-1960 Stephanie Laffer Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES GORDON‘S GHOSTS: BRITISH MAJOR-GENERAL CHARLES GEORGE GORDON AND HIS LEGACIES, 1885-1960 By STEPHANIE LAFFER A Dissertation submitted to the Department of History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2010 Copyright © 2010 Stephanie Laffer All Rights Reserve The members of the committee approve the dissertation of Stephanie Laffer defended on February 5, 2010. __________________________________ Charles Upchurch Professor Directing Dissertation __________________________________ Barry Faulk University Representative __________________________________ Max Paul Friedman Committee Member __________________________________ Peter Garretson Committee Member __________________________________ Jonathan Grant Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members. ii For my parents, who always encouraged me… iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This dissertation has been a multi-year project, with research in multiple states and countries. It would not have been possible without the generous assistance of the libraries and archives I visited, in both the United States and the United Kingdom. However, without the support of the history department and Florida State University, I would not have been able to complete the project. My advisor, Charles Upchurch encouraged me to broaden my understanding of the British Empire, which led to my decision to study Charles Gordon. Dr. Upchurch‘s constant urging for me to push my writing and theoretical understanding of imperialism further, led to a much stronger dissertation than I could have ever produced on my own. -

Rifles Regimental Road

THE RIFLES CHRONOLOGY 1685-2012 20140117_Rifles_Chronology_1685-2012_Edn2.Docx Copyright 2014 The Rifles Trustees http://riflesmuseum.co.uk/ No reproduction without permission - 2 - CONTENTS 5 Foreword 7 Design 9 The Rifles Representative Battle Honours 13 1685-1756: The Raising of the first Regiments in 1685 to the Reorganisation of the Army 1751-1756 21 1757-1791: The Seven Years War, the American War of Independence and the Affiliation of Regiments to Counties in 1782 31 1792-1815: The French Revolutionary Wars, the Napoleonic Wars and the War of 1812 51 1816-1881: Imperial Expansion, the First Afghan War, the Crimean War, the Indian Mutiny, the Formation of the Volunteer Force and Childers’ Reforms of 1881 81 1882-1913: Imperial Consolidation, the Second Boer War and Haldane’s Reforms 1906-1912 93 1914-1918: The First World War 129 1919-1938: The Inter-War Years and Mechanisation 133 1939-1945: The Second World War 153 1946-1988: The End of Empire and the Cold War 165 1989-2007: Post Cold War Conflict 171 2007 to Date: The Rifles First Years Annex A: The Rifles Family Tree Annex B: The Timeline Map 20140117_Rifles_Chronology_1685-2012_Edn2.Docx Copyright 2014 The Rifles Trustees http://riflesmuseum.co.uk/ No reproduction without permission - 3 - 20140117_Rifles_Chronology_1685-2012_Edn2.Docx Copyright 2014 The Rifles Trustees http://riflesmuseum.co.uk/ No reproduction without permission - 4 - FOREWORD by The Colonel Commandant Lieutenant General Sir Nick Carter KCB CBE DSO The formation of The Rifles in 2007 brought together the histories of the thirty-five antecedent regiments, the four forming regiments, with those of our territorials. -

The Law Relating to Officers in the Army

F .. ----·······-_-·--·------·--~ F· r· J-, Jf J3f f. i i ] udge ftdvooaie 9u,..L-l._ U.S. flnny. I · 1 ~-~P. ......~ THE LAW RELATING TO OFFICERS IN THE ARMY, q. 9l~.. THE LA "\V RELATING TO OFFICERS IN THE AR~IY. BY HARRIS PRENDERGAST, OF LINCOLN'S INN, ESQ., BARRISTER-AT-LAW. REVISE!) EPITION. LONDON: PARKER, FURNIV ALL, AND PARKER, MILITARY LIBRARY, WHITEHALL. MDCCCLV. LONDON': PRINTED BY GEORGE PHIPPS, RA..~ELJ.GH STREET, EATON SQUARE, PREFACE TO FIRST EDITION. THE preparation of the following Work was sug gested by my brother, Lieutenant William Grant Prendergast, of the 8th Bengal Cavalry*, Persian Interpreter on the Staff of Lord Gough, Commander in-chief in India ; and from the same quarter much valuable assistance was originally derived, both as to the selection of topics, and the mode of treating them. Without the help of such military guidance, a mere civilian would have laboured under great disadvantages; and the merit, if any, of the Work, is therefore attributable to my coadjutor alone. For the composition, however, I am alone responsible. Officers in the Army are subject to a variety of special laws and legal· principles, which deeply affect their professional and private rights; and it is hoped that a Work, which endeavours to develope these subjects in a connected and untechnical form, will not be deemed a superfluous contribution to military literature. With this view, the following pages are by no means so much addressed to lawyers, as to a class of readers whose opportunities of access to legal publications are necessarily very limited; and care has been taken, in all · cases of importance, to set • Now Brevet-1\lfaj~r, and Acting Brigadier on the frontier of the Punjab. -

The Napier Papers

THE NAPIER PAPERS PHILIP V. BLAKE-HILL A. THE FIRST SERIES IN 1956 the Department of Manuscripts incorporated in its collections a series of papers of various members of the Napier family which had been bequeathed by Miss Violet Bunbury Napier, youngest daughter of General William Craig Emilius Napier. They commence with those of the Hon. George Napier, 6th son of Francis, 6th Baron Napier of Merchiston, and continue with those of four of his sons, Charles, George, William, and Richard, and Sir Charles's daughter, Emily. They have been arranged in eighty- eight volumes of papers (Add. MSS. 49086-49172) and twenty-four charters, mostly army commissions (Add. Ch. 75438, 75767, 75769-75790). The first series is divided into sub-sections: (i) the Hon. George Napier, (2) Sir Charles James Napier, (3) Emily Cefalonia^ and William Craig Emilius Napier, (4) Sir George Thomas Napier, (5) Sir William Francis Patrick Napier, and (6) Richard Napier. The relationship between them is shown in the genealogical table. At the end is a section consisting of papers of other members of the family. I. Papers of George and Lady Sarah Napier The Hon. George Napier married en secondes noces Lady Sarah Bunbury, daughter of Charles, 2nd Duke of Richmond, and divorced wife of Sir Thomas Bunbury: she was the famous beauty to whom George III had once proposed. Although some of her corre- spondence is included in this section, the majority of the papers are the official documents and letters of Napier in his capacities as Comptroller of the Royal Laboratory, Woolwich (1782-3),^ Deputy Quartermaster General of the Army (1794 8), and Comptroller of Army Accounts, Ireland (1799-1804). -

The Conquest of Sindh, a Commentary

THE CONQUEST OF SINDH A COMMENTARY BY LIEUT. COLONEL JAMES OUTRAM, C.B. (Later, General Sir James Outram, Bart. G.C.B.) RESIDENT AT SATTARAH Volume I GENERAL SIR CHARLES NAPIER’S NEGOTIATIONS WITH THE AMEERS Reproduced By: Sani Hussain Panhwar California; 2009 Commentary on the book “Conquest of Sindh” Vol. - I, Copyright © www.panhwar.com 1 Commentary on the book “Conquest of Sindh” Vol. - I, Copyright © www.panhwar.com 2 C O N T E N T S INTRODUCTION .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 4 PREFACE. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 6 SECTION I. MATTERS PERSONAL .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 7 SECTION II. THE TREATIES WITH THE AMEERS AND THE CASUS BELLI THENCE SUPPLIED .. .. .. .. .. .. 19 SECTION III. SIR CHARLES NAPIER’S DIPLOMACY— THE CHARGES AGAINST THE AMEERS .. .. .. .. .. 34 SECTION IV. SIR CHARLES NAPIER’S NEGOTIATIONS .. .. .. .. .. 45 SECTION V. ALI MORAD’S INTRIGUES,—MEER ROOSTUM’S FORCED RESIGNATION .. .. .. .. .. .. 57 SECTION VI. THE TENDERING OF THE NEW TREATY .. .. .. .. .. 78 SECTION VII. THE UPPER SINDH CAMPAIGN .. .. .. .. .. .. 99 SECTION VIII. THE MARCH ON EMAUMGHUK, AND CONTEMPORANEOUS NEGOTIATIONS .. .. .. .. 115 SECTION IX. THE NEGOTIATIONS CONTINUED .. .. .. .. .. .. 132 APPENDIX .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 157 Commentary on the book “Conquest of Sindh” Vol. - I, Copyright © www.panhwar.com 3 INTRODUCTION I have reproduced set of four volumes written on the conquest of Sindh. Two of the books were written by Major-General W.F.P. Napier brother of Sir Charles James Napier conquer of Sindh and first Governor General of Sindh. These two volumes were published to clarify the acts and deeds of Charles Napier in justifying his actions against the Ameers of Sindh. The books were originally titled as “ The Conquest of Scinde , with some introductory passages in the life of Major-General Sir Charles Napier”; Volume I and II. -

The Politics of Commemoration: 1957, the British in India and the ‘Sepoy Mutiny’

The Politics of Commemoration: 1957, the British in India and the ‘Sepoy Mutiny’ Crispin Bates University of Edinburgh Research Project: Mutiny at the Margins - the Indian Mutiny / Uprising of 1857 • A 450k two-year project, funded by the UK Arts & Humanities Research Council (AHRC) providing revisionist perspectives on the Indian Uprising of 1857 to coincide with 150th anniversary – www.csas.ed.ac.uk/mutiny • Discreet, but interlocking research strands, concentrating on the involvement of socially marginal groups and marginal histories often written out of traditional 'elite' historiography of 1857 • My contribution - adivasi insurgency + post 1857 migration Commemorating Historical Events " ! Memorialising and Commemoration subject to three pressures ! Desire of historians to ascertain ‘the truth’ ! Sentimental recollections / popular perceptions ! Current political exigencies – which might obliterate either or both of the above " ! 1857 is unusual in that British recollections and Indian popular perceptions are diametrically opposed " ! Contention of this paper is that PRESENT political exigencies have tended to unusually dominate the re- telling of this crucial aspect of modern Indian history The Nature of 1857 " ! A brutal conflict marked by atrocities on all sides " ! Crucial to the ending of British indirect rule of overseas territories in Asia and Africa through trading corporations " ! Marked the end of the East India Company and of the Timurid dynasty of Bahadur Shah II " ! Brought India under the direct control of the British -

'No Troops but the British': British National Identity and the Battle For

‘No Troops but the British’: British National Identity and the Battle for Waterloo Kyle van Beurden BA/BBus (Accy) (QUT), BA Honours (UQ) A thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2015 School of Historical and Philosophical Inquiry British National Identity and the Battle for Waterloo Kyle van Beurden Abstract In the ‘long eighteenth-century’ British national identity was superimposed over pre-existing identities in Britain in order to bring together the somewhat disparate, often warring, states. This identity centred on war with France; the French were conceptualised as the ‘other’, being seen by the British as both different and inferior. For many historians this identity, built in reaction and opposition to France, dissipated following the defeat of Napoleon at Waterloo in 1815, as Britain gradually introduced changes that allowed broader sections of the population to engage in the political process. A new militaristic identity did not reappear in Britain until the 1850s, following the Crimean War and the Indian Mutiny. This identity did not fixate on France, but rather saw all foreign nations as different and, consequently, inferior. An additional change was the increasing public interest in the army and war, more generally. War became viewed as a ‘pleasurable endeavour’ in which Britons had an innate skill and the army became seen as representative of that fact, rather than an outlet to dispose of undesirable elements of the population, as it had been in the past. British identity became increasingly militaristic in the lead up to the First World War. However, these two identities have been seen as separate phenomena, rather than the later identity being a progression of the earlier construct. -

May 2004 Front

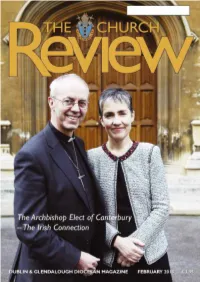

LENT 2013 COUNT YOUR BLESSINGS Give thanks and celebrate the good things in your life this Lent with our thought-provoking Count Your Blessings calendar enclosed in this edition of the Review. Each day from Ash Wednesday to Easter Sunday, forty bite-sized reflections will inspire you to give thanks for the blessings in your life, and enable you to step out in prayer and action to help FKDQJH WKH OLYHV RI WKH ZRUOG·V SRRUHVW communities. To order more copies please ring 611 0801 or write to us at: Christian Aid, 17 Clanwilliam Terrace Dublin 2 8 9 9 6 Y H C www.christianaid.ie CHURCH OF IRE LAND UNITE D DIOCE S ES CHURCH REVIEW OF DUB LIN AND GLE NDALOUGH ISSN 0790-0384 The Most Reverend Michael Jackson, Archbishop of Dublin and Bishop of Glendalough, Church Review is published monthly Primate of Ireland and Metropolitan. and usually available by the first Sunday. Please order your copy from your Parish by annual sub scription. €40 for 2013 AD. POSTAL SUBSCRIIPTIIONS//CIIRCULATIION Archbishop’s Lette r Copies by post are available from: Charlotte O’Brien, ‘Mountview’, The Paddock, Enniskerry, Co. Wicklow. E: [email protected] T: 086 026 5522. FEBRUARY 2013 The cost is the subscription and appropriate postage. I was struck early in the New Year, while leafing through a newspaper, to find the following statement: Happiness and vulnerability are often the same thing. It was not a religious paper and in COPY DEADLIINE no way did the sentiment it voiced set out to be theological. However, it got me thinking, as often All editorial material MUST be with the I find to be the case with certain things which say something from their own context into another Editor by 15th of the preceeding and quite different context, about something important to me.