Baby Steps Or One Fell Swoop?: the Incremental Extension of Rights Is Not a Defensible Strategy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 and 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 AND 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 Committee: Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Dr. John Makay Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Ron E. Shields Dr. Don McQuarie © 2007 Bradley C. Klypchak All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Between 1984 and 1991, heavy metal became one of the most publicly popular and commercially successful rock music subgenres. The focus of this dissertation is to explore the following research questions: How did the subculture of heavy metal music between 1984 and 1991 evolve and what meanings can be derived from this ongoing process? How did the contextual circumstances surrounding heavy metal music during this period impact the performative choices exhibited by artists, and from a position of retrospection, what lasting significance does this particular era of heavy metal merit today? A textual analysis of metal- related materials fostered the development of themes relating to the selective choices made and performances enacted by metal artists. These themes were then considered in terms of gender, sexuality, race, and age constructions as well as the ongoing negotiations of the metal artist within multiple performative realms. Occurring at the juncture of art and commerce, heavy metal music is a purposeful construction. Metal musicians made performative choices for serving particular aims, be it fame, wealth, or art. These same individuals worked within a greater system of influence. Metal bands were the contracted employees of record labels whose own corporate aims needed to be recognized. -

Mingus, Nietzschean Aesthetics, and Mental Theater

Liminalities: A Journal of Performance Studies Vol. 16, No. 3 (2020) Music Performativity in the Album: Charles Mingus, Nietzschean Aesthetics, and Mental Theater David Landes This article analyzes a canonical jazz album through Nietzschean and perfor- mance studies concepts, illuminating the album as a case study of multiple per- formativities. I analyze Charles Mingus’ The Black Saint and the Sinner Lady as performing classical theater across the album’s images, texts, and music, and as a performance to be constructed in audiences’ minds as the sounds, texts, and visuals never simultaneously meet in the same space. Drawing upon Nie- tzschean aesthetics, I suggest how this performative space operates as “mental the- ater,” hybridizing diverse traditions and configuring distinct dynamics of aesthetic possibility. In this crossroads of jazz traditions, theater traditions, and the album format, Mingus exhibits an artistry between performing the album itself as im- agined drama stage and between crafting this space’s Apollonian/Dionysian in- terplay in a performative understanding of aesthetics, sound, and embodiment. This case study progresses several agendas in performance studies involving music performativity, the concept of performance complex, the Dionysian, and the album as a site of performative space. When Charlie Parker said “If you don't live it, it won't come out of your horn” (Reisner 27), he captured a performativity inherent to jazz music: one is lim- ited to what one has lived. To perform jazz is to make yourself per (through) form (semblance, image, likeness). Improvising jazz means more than choos- ing which notes to play. It means steering through an infinity of choices to craft a self made out of sound. -

Why Jazz Still Matters Jazz Still Matters Why Journal of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences Journal of the American Academy

Dædalus Spring 2019 Why Jazz Still Matters Spring 2019 Why Dædalus Journal of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences Spring 2019 Why Jazz Still Matters Gerald Early & Ingrid Monson, guest editors with Farah Jasmine Griffin Gabriel Solis · Christopher J. Wells Kelsey A. K. Klotz · Judith Tick Krin Gabbard · Carol A. Muller Dædalus Journal of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences “Why Jazz Still Matters” Volume 148, Number 2; Spring 2019 Gerald Early & Ingrid Monson, Guest Editors Phyllis S. Bendell, Managing Editor and Director of Publications Peter Walton, Associate Editor Heather M. Struntz, Assistant Editor Committee on Studies and Publications John Mark Hansen, Chair; Rosina Bierbaum, Johanna Drucker, Gerald Early, Carol Gluck, Linda Greenhouse, John Hildebrand, Philip Khoury, Arthur Kleinman, Sara Lawrence-Lightfoot, Alan I. Leshner, Rose McDermott, Michael S. McPherson, Frances McCall Rosenbluth, Scott D. Sagan, Nancy C. Andrews (ex officio), David W. Oxtoby (ex officio), Diane P. Wood (ex officio) Inside front cover: Pianist Geri Allen. Photograph by Arne Reimer, provided by Ora Harris. © by Ross Clayton Productions. Contents 5 Why Jazz Still Matters Gerald Early & Ingrid Monson 13 Following Geri’s Lead Farah Jasmine Griffin 23 Soul, Afrofuturism & the Timeliness of Contemporary Jazz Fusions Gabriel Solis 36 “You Can’t Dance to It”: Jazz Music and Its Choreographies of Listening Christopher J. Wells 52 Dave Brubeck’s Southern Strategy Kelsey A. K. Klotz 67 Keith Jarrett, Miscegenation & the Rise of the European Sensibility in Jazz in the 1970s Gerald Early 83 Ella Fitzgerald & “I Can’t Stop Loving You,” Berlin 1968: Paying Homage to & Signifying on Soul Music Judith Tick 92 La La Land Is a Hit, but Is It Good for Jazz? Krin Gabbard 104 Yusef Lateef’s Autophysiopsychic Quest Ingrid Monson 115 Why Jazz? South Africa 2019 Carol A. -

Disposable Women and Other Myths of Global Gapitalism

Disposable Women and Other Myths of Global Gapitalism Melissa W. Wright l) Routledoe | \ r"yror a rr.nciicroup N€wYql Lmdm Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Croup, an inlorma business Contents Acknowledgments xl 1 Introduction: Disposable Women and Other Myths of Global Capitalism I Storylines 2 Disposable Daughters and Factory Fathers 23 3 Manufacturing Bodies 45 4 The Dialectics of Still Life: Murder,'il7omen, and Disposability 7l II Disruptions 5 Maquiladora Mestizas and a Feminist Border Politics 93 6 Crossing the FactorY Frontier 123 7 Paradoxes and Protests 151 Notes 171 Bibliography 177 Index r87 Acknowledgments I wrote this book in fits and starts over several years, during which time I benefited from the support of numerous people. I want to say from the outset that I dedicate this book to my parenrs, and I wish I had finished the manuscript in time for my father to see ir. My father introduced me to the Mexico-U.S. border at a young age when he took me on his many trips while working for rhe State of Texas. As we traveled by car and by train into Mexico and along the bor- der, he instilled in me an appreciation for the art of storytelling. My mother, who taught high school in Bastrop, Texas for some 30 years, has always been an inspiration. Her enthusiasm for reaching those students who want to learn and for not letting an underfunded edu- cational bureaucracy lessen her resolve set high standards for me. I am privileged to have her unyielding affection to this day. -

The Journal of the Duke Ellington Society Uk Volume 23 Number 3 Autumn 2016

THE JOURNAL OF THE DUKE ELLINGTON SOCIETY UK VOLUME 23 NUMBER 3 AUTUMN 2016 nil significat nisi pulsatur DUKE ELLINGTON SOCIETY UK http://dukeellington.org.uk DESUK COMMITTEE HONORARY MEMBERS OF DESUK Art Baron CHAIRMAN: Geoff Smith John Lamb Vincent Prudente VICE CHAIRMAN: Mike Coates Monsignor John Sanders SECRETARY: Quentin Bryar Tel: 0208 998 2761 Email: [email protected] HONORARY MEMBERS SADLY NO LONGER WITH US TREASURER: Grant Elliot Tel: 01284 753825 Bill Berry (13 October 2002) Email: [email protected] Harold Ashby (13 June 2003) Jimmy Woode (23 April 2005) MEMBERSHIP SECRETARY: Mike Coates Tel: 0114 234 8927 Humphrey Lyttelton (25 April 2008) Email: [email protected] Louie Bellson (14 February 2009) Joya Sherrill (28 June 2010) PUBLICITY: Chris Addison Tel:01642-274740 Alice Babs (11 February, 2014) Email: [email protected] Herb Jeffries (25 May 2014) MEETINGS: Antony Pepper Tel: 01342-314053 Derek Else (16 July 2014) Email: [email protected] Clark Terry (21 February 2015) Joe Temperley (11 May, 2016) COMMITTEE MEMBERS: Roger Boyes, Ian Buster Cooper (13 May 2016) Bradley, George Duncan, Frank Griffith, Frank Harvey Membership of Duke Ellington Society UK costs £25 SOCIETY NOTICES per year. Members receive quarterly a copy of the Society’s journal Blue Light. DESUK London Social Meetings: Civil Service Club, 13-15 Great Scotland Yard, London nd Payment may be made by: SW1A 2HJ; off Whitehall, Trafalgar Square end. 2 Saturday of the month, 2pm. Cheque, payable to DESUK drawn on a Sterling bank Antony Pepper, contact details as above. account and sent to The Treasurer, 55 Home Farm Lane, Bury St. -

Corrective Progressivity (Please Do Not Quote Without Author’S Permission) Prof Eric Kades* William & Mary Law School

Corrective Progressivity (Please Do Not Quote Without Author’s Permission) Prof Eric Kades* William & Mary Law School I. Introduction .................................................................................................................................................... 2 II. Income Inequality, Federal Tax Progressivity, & State Tax Regressivity .................................... 3 A. The Inequality Revolution Since 1980 ............................................................................................... 3 B. The Normative Case for Progressive Taxation ................................................................................ 7 C. Federal Tax Progressivity .................................................................................................................... 10 D. State Tax Regressivity ........................................................................................................................... 14 III. A Model of Corrective Progressivity ................................................................................................... 19 A. An Overview ........................................................................................................................................... 19 B. Illustrative Examples ............................................................................................................................ 21 C. The General Model .............................................................................................................................. -

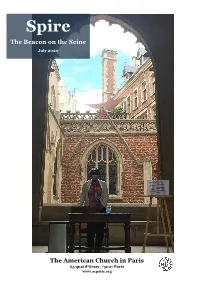

ACP Spire Jul2020

Spire The Beacon on the Seine July 2020 The American Church in Paris 65 quai d’Orsay, 75007 Paris www.acparis.org In this issue Thoughts from The Rev. Dr. Scott Herr 3 Note from the editor, by Alison Benney 4 Journeys, by Revs. Jodi and Doug Fondell 5 Welcome Odette Lockwood-Stewart, by Marleigh White 6 Looking forward, by Rev. Odette Lockwood-Stewart 7 Say what? Scott’s pearls of wisdom, by Valentina Lana 8 Color my world, by Fred Gramann 9 Front page of the Spire: April 2008, by Gigi Oyog 10 In the beginning, by Alison Benney 11 Pastor and boss: Staff reflections 12-13 Bible readings for July, by Heather Scott 14 Called home: in memory 14 What’s up in Paris: March event listings, by Karen Albrecht 15 Then and now 16 2008-2020: A brief list of accomplishments, by Rev. Scott Herr 17 Confinement: Talking to the choir, by Rebecca Brite 18 Alpha goes online, by MaryClaire King 19 ACP Congregational Meeting: Zoom! by Kerry Lieury 20 ACP finances, by Don Farnan 21 A hybrid Bloom, by Michael Bahati 22 Feeding the hungry, by Tom Wilscam 23 Mission Outreach to India, by Pascale Deforge 24 News from Rafiki Village, by Patti Lafage 25 Celebrating small miracles in the time of coronavirus, by Karen Albrecht 26 James Tissot: Ambiguous figure of modernity, by Karen Marin 27 After 12 years in Paris, Pastor Scott Herr and family are hitting the road for their next adventure, in New Canaan, Connecticut. 2 ACP Spire, July 2020 Thoughts from The Rev. -

Steve Lacy Sextet the Gleam Mp3, Flac, Wma

Steve Lacy Sextet The Gleam mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Jazz Album: The Gleam Country: Sweden Style: Free Jazz, Avant-garde Jazz MP3 version RAR size: 1387 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1209 mb WMA version RAR size: 1505 mb Rating: 4.5 Votes: 666 Other Formats: AU VQF VOX ASF MP2 AC3 AIFF Tracklist 1 Gay Paree Bop 9:00 2 Napping 8:57 3 The Gleam 7:00 4 As Usual 12:12 5 Keepsake 10:22 6 Napping (Take 2) 9:20 Companies, etc. Recorded At – Sound Ideas Studios Credits Alto Saxophone, Soprano Saxophone – Steve Potts Bass – Jean-Jacques Avenel Drums – Oliver Johnson Executive-Producer – Keith Knox Piano – Bobby Few Recorded By, Mixed By – David Baker Soprano Saxophone, Composed By, Mixed By, Producer – Steve Lacy Vocals, Violin – Irène Aebi* Notes Recorded on 16-18 July 1986 at Sound Ideas Studio, NYC. Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year SHLP 102 Steve Lacy Sextet* The Gleam (LP, Album) Silkheart SHLP 102 Sweden 1987 Related Music albums to The Gleam by Steve Lacy Sextet Jazz Steve Lacy / Mal Waldron - Herbe De L'oubli - Snake-Out Jazz Rova Saxophone Quartet, Kyle Bruckmann, Henry Kaiser - Steve Lacy's Saxophone Special Revisited Jazz Steve Lacy - Anthem Jazz Steve Lacy - Epistrophy Jazz Steve Lacy - Momentum Jazz Steve Lacy - Solo: Live At Unity Temple Jazz Steve Lacy - Axieme Jazz Steve Lacy Quartet Featuring Charles Tyler - One Fell Swoop Jazz Steve Lacy - Scratching The Seventies / Dreams Jazz Mal Waldron With The Steve Lacy Quintet - Mal Waldron With The Steve Lacy Quintet. -

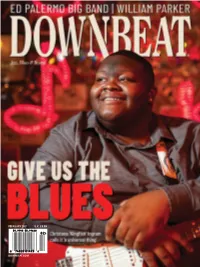

Downbeat.Com February 2021 U.K. £6.99

FEBRUARY 2021 U.K. £6.99 DOWNBEAT.COM FEBRUARY 2021 DOWNBEAT 1 FEBRUARY 2021 VOLUME 88 / NUMBER 2 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Reviews Editor Dave Cantor Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Will Dutton Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile Vice President of Sales 630-359-9345 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney Vice President of Sales 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Grace Blackford 630-359-9358 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Jeff Johnson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Sean J. O’Connell, Chris Walker, Josef Woodard, Scott Yanow; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Andrea Canter; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, Jennifer Odell; New York: Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Philip Freeman, Stephanie Jones, Matthew Kassel, Jimmy Katz, Suzanne Lorge, Phillip Lutz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Bill Milkowski, Allen Morrison, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian; Philadelphia: Shaun Brady; Portland: Robert Ham; San Francisco: Yoshi Kato, Denise Sullivan; Seattle: Paul de Barros; Washington, D.C.: Willard Jenkins, John Murph, Michael Wilderman; Canada: J.D. Considine, James Hale; France: Jean Szlamowicz; Germany: Hyou Vielz; Great Britain: Andrew Jones; Portugal: José Duarte; Romania: Virgil Mihaiu; Russia: Cyril Moshkow. -

The Avant-Garde in Jazz As Representative of Late 20Th Century American Art Music

THE AVANT-GARDE IN JAZZ AS REPRESENTATIVE OF LATE 20TH CENTURY AMERICAN ART MUSIC By LONGINEU PARSONS A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2017 © 2017 Longineu Parsons To all of these great musicians who opened artistic doors for us to walk through, enjoy and spread peace to the planet. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank my professors at the University of Florida for their help and encouragement in this endeavor. An extra special thanks to my mentor through this process, Dr. Paul Richards, whose forward-thinking approach to music made this possible. Dr. James P. Sain introduced me to new ways to think about composition; Scott Wilson showed me other ways of understanding jazz pedagogy. I also thank my colleagues at Florida A&M University for their encouragement and support of this endeavor, especially Dr. Kawachi Clemons and Professor Lindsey Sarjeant. I am fortunate to be able to call you friends. I also acknowledge my friends, relatives and business partners who helped convince me that I wasn’t insane for going back to school at my age. Above all, I thank my wife Joanna for her unwavering support throughout this process. 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .................................................................................................. 4 LIST OF EXAMPLES ...................................................................................................... 7 ABSTRACT -

Wedding Issue

Catskill Mountain Region February 2013 GUIDEwww.catskillregionguide.com WEDDING ISSUE The Catskill Mountain Foundation Presents THe BlueS Hall oF Fame NIgHT aT THe orpHeum New York Blues Hall of Fame Induction Ceremony and Concert This performance is funded, in part, by Friends of the Orpheum (FOTO) with recent inductees Professor Louie & The Crowmatix, Bill Sims, Jr., Michael Packer, and Sonny Rock Awards going to Big Joe Fitz, Kerry Kearney and more great performers to be announced with Greg Dayton opening and special guests the Greene Room Show Choir Saturday, February 16, 2013 8pm (doors open at 7pm) Tickets: $25 in advance, $30 at the door For tickets, visit www.catskillmtn.org or call 518 263 2063 Orpheum Performing Arts Center • 6022 Main St., Tannersville, NY 12485 TABLE OF www.catskillregionguide.com VOLUME 28, NUMBER 2 February 2013 PUBLISHERS Peter Finn, Chairman, Catskill Mountain Foundation Sarah Finn, President, Catskill Mountain Foundation CONTENTS EDITORIAL DIRECTOR, CATSKILL MOUNTAIN FOUNDATION Sarah Taft ADVERTISING SALES Rita Adami • Steve Friedman Garan Santicola • Albert Verdesca CONTRIBUTING WRITERS Tara Collins, Jeff Senterman, Carol and David White Additional content provided by Brandpoint Content. ADMINISTRATION & FINANCE Candy McKee Toni Perretti Laureen Priputen PRINTING Catskill Mountain Printing DISTRIBUTION Catskill Mountain Foundation EDITORIAL DEADLINE FOR NEXT ISSUE: January 6 The Catskill Mountain Region Guide is published 12 times a year by the Catskill Mountain Foundation, Inc., Main Street, PO Box On the cover: Wedding at the summit of Hunter Mountain. 924, Hunter, NY 12442. If you have events or programs that you would like to have covered, please send them by e-mail to tafts@ Photo by John Iannelli, www.iannelliphoto.com. -

GUNTHER SCHULLER NEA Jazz Master (2008)

1 Funding for the Smithsonian Jazz Oral History Program NEA Jazz Master interview was provided by the National Endowment for the Arts. GUNTHER SCHULLER NEA Jazz Master (2008) Interviewee: Gunther Schuller (November 22, 1925 - ) Interviewer: Steve Schwartz with recording engineer Ken Kimery Date: June 29-30, 2008 Repository: Archives Center, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution Description: Transcript, 87 pp. Schwartz: This is Steve Schwartz from WGBH radio in Boston. We’re at the home of Gunther Schuller on Dudley Road in Newton Centre, Massachusetts, to do an oral history for the Smithsonian Oral History Jazz Program, if that’s the right title. Close enough? Hello Gunther. Schuller: Hello. Good to see you. Schwartz: Thank you for opening your doors to us. We should start at the beginning, or as far back to the beginning as we can go. I’d love to have you talk about your childhood, your growing up in New York, and whatever memories you have – your parents, who they are, who they were – things like that to get us started. Schuller: I was born in New York. Many people think I was born in Germany, with my German name and I speak fluent German, but I was born in New York City. My parents came over from Germany in 1923. They were not married. They didn’t know each other. They just happened to leave more or less the same time, when the inflation in Germany was so crazy that a loaf of bread cost not 40, 400, 4,000, but 4-million marks.