GUNTHER SCHULLER NEA Jazz Master (2008)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 and 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 AND 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 Committee: Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Dr. John Makay Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Ron E. Shields Dr. Don McQuarie © 2007 Bradley C. Klypchak All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Between 1984 and 1991, heavy metal became one of the most publicly popular and commercially successful rock music subgenres. The focus of this dissertation is to explore the following research questions: How did the subculture of heavy metal music between 1984 and 1991 evolve and what meanings can be derived from this ongoing process? How did the contextual circumstances surrounding heavy metal music during this period impact the performative choices exhibited by artists, and from a position of retrospection, what lasting significance does this particular era of heavy metal merit today? A textual analysis of metal- related materials fostered the development of themes relating to the selective choices made and performances enacted by metal artists. These themes were then considered in terms of gender, sexuality, race, and age constructions as well as the ongoing negotiations of the metal artist within multiple performative realms. Occurring at the juncture of art and commerce, heavy metal music is a purposeful construction. Metal musicians made performative choices for serving particular aims, be it fame, wealth, or art. These same individuals worked within a greater system of influence. Metal bands were the contracted employees of record labels whose own corporate aims needed to be recognized. -

The Manatee PIANO MUSIC of the Manatee BERNARD

The Manatee PIANO MUSIC OF The Manatee BERNARD HOFFER TROY1765 PIANO MUSIC OF Seven Preludes for Piano (1975) 15 The Manatee [2:36] 16 Stridin’ Thru The Olde Towne 1 Prelude [2:40] 2 Cello [2:47] During Prohibition In Search Of A Drink [2:42] 3 All Over The Piano [1:21] Randall Hodgkinson, piano 4 Ships Passing [4:12] (2014) BERNARD HOFFER 5 Prelude [1:24] Events & Excursions for Two Pianos 6 Calypso [3:52] 17 Big Bang Theory [3:15] 7 Franz Liszt Plays Ragtime [3:28] 18 Running [3:19] Randall Hodgkinson, piano 19 Wexford Noon [2:29] 20 Reverberations [3:12] Nine New Preludes for Piano (2016) 21 On The I-93 [2:23] Randall Hodgkinson & Leslie Amper, pianos 8 Undulating Phantoms [1:08] BERNARD HOFFER 9 A Walk In The Park [2:39] 10 Speed Chess [2:17] 22 Naked (2010) [5:05] Randall Hodgkinson, piano 11 Valse Sentimental [3:30] 12 Rabbits [1:06] Total Time = 60:03 13 Spirals [1:40] 14 Canon Inverso [1:44] PIANO MUSIC OF TROY1765 WWW.ALBANYRECORDS.COM TROY1765 ALBANY RECORDS U.S. 915 BROADWAY, ALBANY, NY 12207 TEL: 518.436.8814 FAX: 518.436.0643 ALBANY RECORDS U.K. BOX 137, KENDAL, CUMBRIA LA8 0XD TEL: 01539 824008 © 2019 ALBANY RECORDS MADE IN THE USA DDD WARNING: COPYRIGHT SUBSISTS IN ALL RECORDINGS ISSUED UNDER THIS LABEL. The Manatee PIANO MUSIC OF The Manatee BERNARD HOFFER WWW.ALBANYRECORDS.COM TROY1765 ALBANY RECORDS U.S. 915 BROADWAY, ALBANY, NY 12207 TEL: 518.436.8814 FAX: 518.436.0643 ALBANY RECORDS U.K. -

Night Passages the Tunnel Visions of Urban Explorer Steve Duncan

SPRING 2010 COLUMBIA MAGAZINE Night Passages The tunnel visions of urban explorer Steve Duncan C1_FrontCover.indd C1 3/9/10 1:04 PM Process CyanProcess MagentaProcess YellowProcess BlackPANTONE 877 C CONTENTS Spring 2010 12 18 24 DEPARTMENTS FEATURES 2 Letters 12 The Night Hunter By Paul Hond 6 College Walk Urban explorer and photographer Steve Duncan Preview From the Bridge . approaches history from a different perspective. Aftershocks . Aliments of Style . Two Poems by Rachel Wetzsteon 18 Defending the University Former provost Jonathan R. Cole, author of 36 In the City of New York The Great American University, discusses the If grace can be attained through repetition, need to protect a vital national resource. WKCR’s Phil Schaap is a bodhisattva of bop. After 40 years, he’s still enlightening us. 24 X-Ray Specs By David J. Craig 40 News Some celestial bodies are so hot they’re invisible. Scientists have invented a telescope that will bring 48 Newsmakers them to light. 50 Explorations 28 Dateline: Iran By Caleb Daniloff 52 Reviews Kelly Niknejad launched Tehran Bureau to change the way we read and think about Iran. 62 Classifi eds 32 Seven Years: A Short Story 64 Finals By Herbert Gold What happens when the girl next door decides to move away? Cover: Self-portrait of Steve Duncan, Old Croton Aqueduct, Upper Manhattan, 2006 1 ToC_r1.indd 1 3/8/10 5:21 PM letters THE BIG HURT celiac disease (“Against the Grain,” Win- I was about 10 when I visited the pool I enjoyed the feature about Kathryn Bigelow ter 2009–10). -

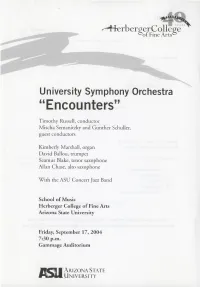

University Symphony Orchestra "Encounters"

FierbergerCollegeYEARS of Fine Arts University Symphony Orchestra "Encounters" Timothy Russell, conductor Mischa Semanitzky and Gunther Schuller, guest conductors Kimberly Marshall, organ David Ballou, trumpet Seamus Blake, tenor saxophone Allan Chase, alto saxophone With the ASU Concert Jazz Band School of Music Herberger College of Fine Arts Arizona State University Friday, September 17, 2004 7:30 p.m. Gammage Auditorium ARIZONA STATE M UNIVERSITY Program Overture to Nabucco Giuseppe Verdi (1813 — 1901) Timothy Russell, conductor Symphony No. 3 (Symphony — Poem) Aram ifyich Khachaturian (1903 — 1978) Allegro moderato, maestoso Allegro Andante sostenuto Maestoso — Tempo I (played without pause) Kimberly Marshall, organ Mischa Semanitzky, conductor Intermission Remarks by Dean J. Robert Wills Remarks by Gunther Schuller Encounters (2003) Gunther Schuller (b.1925) I. Tempo moderato II. Quasi Presto III. Adagio IV. Misterioso (played without pause) Gunther Schuller, conductor *Out of respect for the performers and those audience members around you, please turn all beepers, cell phones and watches to their silent mode. Thank you. Program Notes Symphony No. 3 – Aram Il'yich Khachaturian In November 1953, Aram Khachaturian acted on the encouraging signs of a cultural thaw following the death of Stalin six months earlier and wrote an article for the magazine Sovetskaya Muzika pleading for greater creative freedom. The way forward, he wrote, would have to be without the bureaucratic interference that had marred the creative efforts of previous years. How often in the past, he continues, 'have we listened to "monumental" works...that amounted to nothing but empty prattle by the composer, bolstered up by a contemporary theme announced in descriptive titles.' He was surely thinking of those countless odes to Stalin, Lenin and the Revolution, many of them subdivided into vividly worded sections; and in that respect Khachaturian had been no less guilty than most of his contemporaries. -

Senior Class Protests SGA Senior Week Budget Cuts

PUBLISHED BY THE STUDENTS OF TRINITY COLLEGE SINCE 1904 Senior Class Protests SGA Composer Visits Trinity... Senior Week Budget Cuts BY IAN LANG The problem started when senior class had to cut corners News Editor the Senior Class committee re- in order to finish the budget in worked their budget from the enough time to get funding for previous year. "Last year Eric the senior budget, and that is Last Tuesday, at their weekly Decosta was in charge of all were the problem came in." meeting, the Student Govern- class budgets, but this year the The main discrepancies arose ment Association Budget Com- seniors decided to change around the issue of how much mittee voted unanimously to things around" stated Nardelli, money should be budgeted for cut the funding for this years' "I recommended that they cre- things like alcohol and enter- Senior Week. The Senior Class ate a budget which would be in tainment. At one specific event Committee had presented a effect from March first on." It is the Senior Class asked for $5,500 budget asking for in excess of this new budget which was dollars for a band, a number $20,000 dollars, but the com- brought before the budget com- which Nardelli felt was too mittee found the budget to be mittee Tuesday. high. "Last year the band at se- "greatly inflated," according to Senior class President Brian nior week only cost $2,500 dol- Budget Committee Chairman Gordon, however, disagreed lars. There is no reason it should Mick Nardelli '97, and awarded with Nardelli's assertions. -

Selected Observations from the Harlem Jazz Scene By

SELECTED OBSERVATIONS FROM THE HARLEM JAZZ SCENE BY JONAH JONATHAN A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-Newark Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Graduate Program in Jazz History and Research Written under the direction of Dr. Lewis Porter and approved by ______________________ ______________________ Newark, NJ May 2015 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements Page 3 Abstract Page 4 Preface Page 5 Chapter 1. A Brief History and Overview of Jazz in Harlem Page 6 Chapter 2. The Harlem Race Riots of 1935 and 1943 and their relationship to Jazz Page 11 Chapter 3. The Harlem Scene with Radam Schwartz Page 30 Chapter 4. Alex Layne's Life as a Harlem Jazz Musician Page 34 Chapter 5. Some Music from Harlem, 1941 Page 50 Chapter 6. The Decline of Jazz in Harlem Page 54 Appendix A historic list of Harlem night clubs Page 56 Works Cited Page 89 Bibliography Page 91 Discography Page 98 3 Acknowledgements This thesis is dedicated to all of my teachers and mentors throughout my life who helped me learn and grow in the world of jazz and jazz history. I'd like to thank these special people from before my enrollment at Rutgers: Andy Jaffe, Dave Demsey, Mulgrew Miller, Ron Carter, and Phil Schaap. I am grateful to Alex Layne and Radam Schwartz for their friendship and their willingness to share their interviews in this thesis. I would like to thank my family and loved ones including Victoria Holmberg, my son Lucas Jonathan, my parents Darius Jonathan and Carrie Bail, and my sisters Geneva Jonathan and Orelia Jonathan. -

Ellingtonia a Publication of the Duke Ellington Society, Inc

Ellingtonia A Publication Of The Duke Ellington Society, Inc. Volume XXIV, Number 3 March 2016 William McFadden, Editor Copyright © 2016 by The Duke Ellington Society, Inc., P.O. Box 29470, Washington, D.C. 20017, U.S.A. Web Site: depanorama.net/desociety E-mail: [email protected] This Saturday Night . ‘Hero of the Newport Jazz Festival’. Paul Gonsalves Our March meeting will May 19-23, 2016 New York City bring in the month just like the proverbial lion in Sponsored by The Duke Ellington Center a program selected by Art for the Arts (DECFA) Luby. It promises a Tentative Schedule Announced finely-tuned revisit to some of the greatest tenor Thursday, May 19, 2016 saxophone virtuosity by St. Peter’s Church, 619 Lexington Ave. Paul Gonsalves, other 12:30 - 1:45 Jazz on the Plaza—The Music of Duke than his immortal 16-bar solo on “Diminuendo and Ellington, East 53rd St. and Lexington Ave. at St. Peter’s Crescendo in Blue” at the Newport Jazz Festival in 1956. That’s a lot of territory, considering Paul’s quar- 3:00 - 5:30 “A Drum Is A Woman” - Screenings at The ter century with The Orchestra. In addition to his ex- Paley Center for Media, 25 West 52nd St. pertise on things Gonsalves, Art’s inspiration for this 5:30 - 7:00 Dinner break program comes from a memorable evening a decade ago where the same terrain was visited and expertly 7:15 - 8:00 Gala Opening Reception at St. Peter’s, hosted by the late Ted Shell. “The Jazz Church” - Greetings and welcome from Mercedes Art’s blues-and-ballads-filled listen to the man called Ellington, Michael Dinwiddie (DEFCA) and Ray Carman “Strolling Violins” will get going in our regular digs at (TDES, Inc.) Grace Lutheran Church, 4300—16th Street (at Varnum St.), NW, Washington, DC 20011 on: 8:00 - 9:00 The Duke Ellington Center Big Band - Frank Owens, Musical Director Saturday, 5 March 2016—7:00 PM. -

Entertainmentpage 19 Technique • Friday, October 19, 2007 • 19

ENTERTAINMENTpage 19 Technique • Friday, October 19, 2007 • 19 FLOUNDERING VOLLEY TECH HOSTS MODEL UN Tech’s women’s volleyball team lost Students from Southeastern high ENTERTAINMENT Tuesday to undefeated Clemson. Th eir schools came to attend the 9th annual Page 33 Page 11 Technique • Friday, October 19, 2007 record has dropped to 5-4. Model UN Conference. Fall gets cool with fun festivals Food festival serves it up Atlanta unmasks Echo By Hahnming Lee By Hahnming Lee & Jarrett Oakley Sports Editor Sports Editor/Contributing Writer Taste of Atlanta attracted thousands to sample some of Atlanta’s Th is past weekend saw the inaugural run of a new music festival best food this past weekend at Atlantic Station. Starting Oct. 13, based in Atlanta: the Echo Project, which aimed to inform and this special two-day event hosted several of the most popular promote ecologically friendly advice and knowledge about the and acclaimed restaurants in the area, giving them a chance human footprint that’s destroying the environment. to show off their food to the public. Stands were Some 15,000 green-conscious patrons showed set up on the sidewalks of Atlantic Station, with up to see 80-plus bands on this fi rst of at least 10 chefs and waiters preparing signature dishes for annual music festival extravaganzas Oct. 12-14, people roaming the street. set on the beautiful 350-plus acres of Bouckaert Customers purchased entrance tickets and food Farm just 20 minutes south of Atlanta. coupons for the event that could be spent at vari- Along with a myriad of sponsors and vendors ous stands at their discretion. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Summer, 1963-1964

-•-'" 8ft :: -'•• t' - ms>* '-. "*' - h.- ••• ; ''' ' : '..- - *'.-.•..'•••• lS*-sJ BERKSHIRE MUSIC CENTER see ERICH LEINSDORF, Director Contemporary JMusic Presented under the Auspices of the Fromm zMusic Foundation at TANGLEWOOD 1963 SEMINAR in Contemporary Music Seven sessions will be given on successive Friday afternoons (at 3:15) in the Chamber Music Hall. Four of these will precede the four Fromm Fellows' Concerts, and will consist of a re- hearsal and lecture by the Host of the following Monday Fromm Concert. July 12 AARON COPLAND July 19 GUNTHER SCHULLER July 26 I Twentieth Century Piano Music PAUL JACOBS August 2 YANNIS XENAKIS j August 9 Twentieth Century Choral Music ALFRED NASH PATTERSON & LORNA COOKE de VARON August 16 I LUKAS FOSS August 23 Round Table Discussion of Contemporary Music Yannis Xenakis, Gunther Schuller and lukas foss Composers 9 Forums There will be four Composers' Forums in the Chamber Music Hall: Wednesday, July 24 at 4:00 ] Thursday, August 1 at 8:00 Wednesday, August 7 at 4:00 Thursday, August 15 at 8:00 FROMM FELLOWS' CONCERTS Theatre-Concert Hall Four Monday Evenings at 8:00 'Programs JULY 15 AUGUST 5 AARON COPLAND, Host YANNIS XENAKIS, Host Varese Octandre (1924) Boulez ...Improvisations sur Mallarme, Copland Sextet (1937) No. 2 Chavez Soli (1933) Philippot ...Variations Schoenberg String Quartet No. 2, Op. 10 Mdcbe .. ..Canzone II (1908) Brown, E ...Pentathis Stravinsky Ragtime for Eleven Instruments Marie, E... Polygraphie-Polyphonique (1918) J. Ballif,C ...Double Trio, 35, Nos. 2 and 3 Milhaud... L'Enlevement d'Europe — Op. Xenakis Achorripsis Opera minute (1927) JULY 22 AUGUST 19 GUNTHER SCHULLER, Host LUKAS FOSS, Host Ives Chromatimelodtune Paz .Dedalus, 1950 Schoenberg Herzgewacb.se Goehr... -

Gerry Mulligan Discography

GERRY MULLIGAN DISCOGRAPHY GERRY MULLIGAN RECORDINGS, CONCERTS AND WHEREABOUTS by Gérard Dugelay, France and Kenneth Hallqvist, Sweden January 2011 Gerry Mulligan DISCOGRAPHY - Recordings, Concerts and Whereabouts by Gérard Dugelay & Kenneth Hallqvist - page No. 1 PREFACE BY GERARD DUGELAY I fell in love when I was younger I was a young jazz fan, when I discovered the music of Gerry Mulligan through a birthday gift from my father. This album was “Gerry Mulligan & Astor Piazzolla”. But it was through “Song for Strayhorn” (Carnegie Hall concert CTI album) I fell in love with the music of Gerry Mulligan. My impressions were: “How great this man is to be able to compose so nicely!, to improvise so marvellously! and to give us such feelings!” Step by step my interest for the music increased I bought regularly his albums and I became crazy from the Concert Jazz Band LPs. Then I appreciated the pianoless Quartets with Bob Brookmeyer (The Pleyel Concerts, which are easily available in France) and with Chet Baker. Just married with Danielle, I spent some days of our honey moon at Antwerp (Belgium) and I had the chance to see the Gerry Mulligan Orchestra in concert. After the concert my wife said: “During some songs I had lost you, you were with the music of Gerry Mulligan!!!” During these 30 years of travel in the music of Jeru, I bought many bootleg albums. One was very important, because it gave me a new direction in my passion: the discographical part. This was the album “Gerry Mulligan – Vol. 2, Live in Stockholm, May 1957”. -

New York City a Guide for New Arrivals

New York City A Guide for New Arrivals The Michigan State University Alumni Club of Greater New York www.msuspartansnyc.org Table of Contents 1. About the MSU Alumni Club of Greater New York 3 2. NYC Neighborhoods 4 3. Finding the Right Rental Apartment 8 What should I expect to pay? 8 When should I start looking? 8 How do I find an apartment?8 Brokers 8 Listings 10 Websites 10 Definitions to Know11 Closing the Deal 12 Thinking About Buying an Apartment? 13 4. Getting Around: Transportation 14 5. Entertainment 15 Restaurants and Bars 15 Shows 17 Sports 18 6. FAQs 19 7. Helpful Tips & Resources 21 8. Credits & Notes 22 v1.0 • January 2012 1. ABOUT YOUR CLUB The MSU Alumni Club of Greater New York represents Michigan State University in our nation’s largest metropolitan area and the world’s greatest city. We are part of the Michigan State University Alumni Association, and our mission is to keep us connected with all things Spartan and to keep MSU connected with us. Our programs include Spartan social, athletic and cultural events, fostering membership in the MSUAA, recruitment of MSU students, career networking and other assistance for alumni, and partnering with MSU in its academic and development related activities in the Tri-State area. We have over fifty events every year including the annual wine tasting dinner for the benefit of our endowed scholarship fund for MSU students from this area and our annual picnic in Central Park to which we invite our families and newly accepted MSU students and their families as well. -

MUNI 20101013 Piano 02 – Scott Joplin, King of Ragtime – Piano Rolls

MUNI 20101013 Piano 02 – Scott Joplin, King of Ragtime – piano rolls An der schönen, blauen Donau – Walzer, op. 314 (Johann Strauss, Jr., 1825-1899) Wiener Philharmoniker, Carlos Kleiber. Musikverein Wien, 1. 1. 1989 1 intro A 1:38 2 A 32 D 0:40 3 B 16 A 0:15 4 B 16 0:15 5 C 16 D 0:15 6 C 16 0:15 7 D 16 Bb 0:17 8 C 16 D 0:15 9 E 16 G 0:15 10 E 16 0:15 11 F 16 0:14 12 F 16 0:13 13 modul. 4 ►F 0:05 14 G 16 0:20 15 G 16 0:18 16 H 16 0:14 17 H 16 0:15 18 10+1 ►A 0:10 19 I 16 0:17 20 I 16 0:16 21 J 16 0:13 22 J 16 0:13 23 16+2 ►D 0:16 24 C 16 0:15 25 16 ►F 0:15 26 G 14 0:17 27 11 ►D 0:10 28 A 0:39 29 A1 16 0:16 30 A2 0:12 31 stretta 0:10 The Entertainer (Scott Joplin) (copyright John Stark & Son, Sedalia, 29. 12. 1902) piano roll Classics of Ragtime 0108 32 intro 4 C 0:06 33 A 16 0:23 34 A 16 0:23 35 B 16 0:23 36 B 16 0:23 37 A 16 0:23 38 C 16 F 0:22 39 C 16 0:22 40 modul. 4 ►C 0:05 41 D 16 0:22 42 D 16 0:23 43 The Crush Collision March (Scott Joplin, 1867/68-1917) 4:09 (J.