Corrective Progressivity (Please Do Not Quote Without Author’S Permission) Prof Eric Kades* William & Mary Law School

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 and 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 AND 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 Committee: Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Dr. John Makay Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Ron E. Shields Dr. Don McQuarie © 2007 Bradley C. Klypchak All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Between 1984 and 1991, heavy metal became one of the most publicly popular and commercially successful rock music subgenres. The focus of this dissertation is to explore the following research questions: How did the subculture of heavy metal music between 1984 and 1991 evolve and what meanings can be derived from this ongoing process? How did the contextual circumstances surrounding heavy metal music during this period impact the performative choices exhibited by artists, and from a position of retrospection, what lasting significance does this particular era of heavy metal merit today? A textual analysis of metal- related materials fostered the development of themes relating to the selective choices made and performances enacted by metal artists. These themes were then considered in terms of gender, sexuality, race, and age constructions as well as the ongoing negotiations of the metal artist within multiple performative realms. Occurring at the juncture of art and commerce, heavy metal music is a purposeful construction. Metal musicians made performative choices for serving particular aims, be it fame, wealth, or art. These same individuals worked within a greater system of influence. Metal bands were the contracted employees of record labels whose own corporate aims needed to be recognized. -

ACP Spire Jul2020

Spire The Beacon on the Seine July 2020 The American Church in Paris 65 quai d’Orsay, 75007 Paris www.acparis.org In this issue Thoughts from The Rev. Dr. Scott Herr 3 Note from the editor, by Alison Benney 4 Journeys, by Revs. Jodi and Doug Fondell 5 Welcome Odette Lockwood-Stewart, by Marleigh White 6 Looking forward, by Rev. Odette Lockwood-Stewart 7 Say what? Scott’s pearls of wisdom, by Valentina Lana 8 Color my world, by Fred Gramann 9 Front page of the Spire: April 2008, by Gigi Oyog 10 In the beginning, by Alison Benney 11 Pastor and boss: Staff reflections 12-13 Bible readings for July, by Heather Scott 14 Called home: in memory 14 What’s up in Paris: March event listings, by Karen Albrecht 15 Then and now 16 2008-2020: A brief list of accomplishments, by Rev. Scott Herr 17 Confinement: Talking to the choir, by Rebecca Brite 18 Alpha goes online, by MaryClaire King 19 ACP Congregational Meeting: Zoom! by Kerry Lieury 20 ACP finances, by Don Farnan 21 A hybrid Bloom, by Michael Bahati 22 Feeding the hungry, by Tom Wilscam 23 Mission Outreach to India, by Pascale Deforge 24 News from Rafiki Village, by Patti Lafage 25 Celebrating small miracles in the time of coronavirus, by Karen Albrecht 26 James Tissot: Ambiguous figure of modernity, by Karen Marin 27 After 12 years in Paris, Pastor Scott Herr and family are hitting the road for their next adventure, in New Canaan, Connecticut. 2 ACP Spire, July 2020 Thoughts from The Rev. -

Steve Lacy Sextet the Gleam Mp3, Flac, Wma

Steve Lacy Sextet The Gleam mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Jazz Album: The Gleam Country: Sweden Style: Free Jazz, Avant-garde Jazz MP3 version RAR size: 1387 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1209 mb WMA version RAR size: 1505 mb Rating: 4.5 Votes: 666 Other Formats: AU VQF VOX ASF MP2 AC3 AIFF Tracklist 1 Gay Paree Bop 9:00 2 Napping 8:57 3 The Gleam 7:00 4 As Usual 12:12 5 Keepsake 10:22 6 Napping (Take 2) 9:20 Companies, etc. Recorded At – Sound Ideas Studios Credits Alto Saxophone, Soprano Saxophone – Steve Potts Bass – Jean-Jacques Avenel Drums – Oliver Johnson Executive-Producer – Keith Knox Piano – Bobby Few Recorded By, Mixed By – David Baker Soprano Saxophone, Composed By, Mixed By, Producer – Steve Lacy Vocals, Violin – Irène Aebi* Notes Recorded on 16-18 July 1986 at Sound Ideas Studio, NYC. Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year SHLP 102 Steve Lacy Sextet* The Gleam (LP, Album) Silkheart SHLP 102 Sweden 1987 Related Music albums to The Gleam by Steve Lacy Sextet Jazz Steve Lacy / Mal Waldron - Herbe De L'oubli - Snake-Out Jazz Rova Saxophone Quartet, Kyle Bruckmann, Henry Kaiser - Steve Lacy's Saxophone Special Revisited Jazz Steve Lacy - Anthem Jazz Steve Lacy - Epistrophy Jazz Steve Lacy - Momentum Jazz Steve Lacy - Solo: Live At Unity Temple Jazz Steve Lacy - Axieme Jazz Steve Lacy Quartet Featuring Charles Tyler - One Fell Swoop Jazz Steve Lacy - Scratching The Seventies / Dreams Jazz Mal Waldron With The Steve Lacy Quintet - Mal Waldron With The Steve Lacy Quintet. -

Wedding Issue

Catskill Mountain Region February 2013 GUIDEwww.catskillregionguide.com WEDDING ISSUE The Catskill Mountain Foundation Presents THe BlueS Hall oF Fame NIgHT aT THe orpHeum New York Blues Hall of Fame Induction Ceremony and Concert This performance is funded, in part, by Friends of the Orpheum (FOTO) with recent inductees Professor Louie & The Crowmatix, Bill Sims, Jr., Michael Packer, and Sonny Rock Awards going to Big Joe Fitz, Kerry Kearney and more great performers to be announced with Greg Dayton opening and special guests the Greene Room Show Choir Saturday, February 16, 2013 8pm (doors open at 7pm) Tickets: $25 in advance, $30 at the door For tickets, visit www.catskillmtn.org or call 518 263 2063 Orpheum Performing Arts Center • 6022 Main St., Tannersville, NY 12485 TABLE OF www.catskillregionguide.com VOLUME 28, NUMBER 2 February 2013 PUBLISHERS Peter Finn, Chairman, Catskill Mountain Foundation Sarah Finn, President, Catskill Mountain Foundation CONTENTS EDITORIAL DIRECTOR, CATSKILL MOUNTAIN FOUNDATION Sarah Taft ADVERTISING SALES Rita Adami • Steve Friedman Garan Santicola • Albert Verdesca CONTRIBUTING WRITERS Tara Collins, Jeff Senterman, Carol and David White Additional content provided by Brandpoint Content. ADMINISTRATION & FINANCE Candy McKee Toni Perretti Laureen Priputen PRINTING Catskill Mountain Printing DISTRIBUTION Catskill Mountain Foundation EDITORIAL DEADLINE FOR NEXT ISSUE: January 6 The Catskill Mountain Region Guide is published 12 times a year by the Catskill Mountain Foundation, Inc., Main Street, PO Box On the cover: Wedding at the summit of Hunter Mountain. 924, Hunter, NY 12442. If you have events or programs that you would like to have covered, please send them by e-mail to tafts@ Photo by John Iannelli, www.iannelliphoto.com. -

GUNTHER SCHULLER NEA Jazz Master (2008)

1 Funding for the Smithsonian Jazz Oral History Program NEA Jazz Master interview was provided by the National Endowment for the Arts. GUNTHER SCHULLER NEA Jazz Master (2008) Interviewee: Gunther Schuller (November 22, 1925 - ) Interviewer: Steve Schwartz with recording engineer Ken Kimery Date: June 29-30, 2008 Repository: Archives Center, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution Description: Transcript, 87 pp. Schwartz: This is Steve Schwartz from WGBH radio in Boston. We’re at the home of Gunther Schuller on Dudley Road in Newton Centre, Massachusetts, to do an oral history for the Smithsonian Oral History Jazz Program, if that’s the right title. Close enough? Hello Gunther. Schuller: Hello. Good to see you. Schwartz: Thank you for opening your doors to us. We should start at the beginning, or as far back to the beginning as we can go. I’d love to have you talk about your childhood, your growing up in New York, and whatever memories you have – your parents, who they are, who they were – things like that to get us started. Schuller: I was born in New York. Many people think I was born in Germany, with my German name and I speak fluent German, but I was born in New York City. My parents came over from Germany in 1923. They were not married. They didn’t know each other. They just happened to leave more or less the same time, when the inflation in Germany was so crazy that a loaf of bread cost not 40, 400, 4,000, but 4-million marks. -

Noise & Capitalism

Cover by Emma (E), Mattin (M) and Sara (S) Noise & Capitalism Noise & Capitalism the interesting part, it’s an you copy another persons E: I was just thinking - you were saying that you Is it possible to try to make than male identified bodies was given at school, she is done this, quite often I have interesting challenge for drawing, where S starts what we’ve been talking weren’t sure if this would something, to capture some- writing in the book. I had studying Graphic Design. S compartmentalised my work our exchange. Now we are and I do a version, and I about, I mean I’ve talked work in relation to the as- thing in design that trans- been involved in an exhibi- sent me the work that she and friendships because I saying that you would do pass it to M, and then that about it with you and with signment you’ve been given, mits the relations produced tion called ‘Her Noise’ at and Brit Pavelson made, it is feel self-conscious or un- the design when maybe you becomes the cover. M, about the projection of because of the time, and the in making this cover? I am the South London Gallery a book that tells in both the generous perhaps. think that we should do the M: Yes it sounds interesting you as the expert and, just amount of time that you & Capitalism Noise struggling with this process in 2005, which in some way text and layout, what are the I started to project that design. -

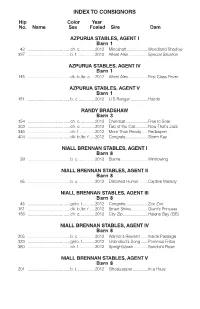

INDEX to CONSIGNORS Hip Color Year No

INDEX TO CONSIGNORS Hip Color Year No. Name Sex Foaled Sire Dam AZPURUA STABLES, AGENT I Barn 1 42 ................................. ......ch. c. .............2012 Mineshaft....................Woodland Shadow 397 ................................. ......b. f. ................2012 Afleet Alex ..................Special Situation AZPURUA STABLES, AGENT IV Barn 1 145 ................................. ......dk. b./br. c. ...2012 Afleet Alex ..................First Class Fever AZPURUA STABLES, AGENT V Barn 1 181 ................................. ......b. c................2012 U S Ranger ................Hairdo RANDY BRADSHAW Barn 3 154 ................................. ......ch. c. .............2012 D'wildcat.....................Free to Soar 303 ................................. ......ch. c. .............2012 Tale of the Cat............Now That's Jazz 345 ................................. ......ch. f. ..............2012 More Than Ready......Redaspen 404 ................................. ......dk. b./br. f......2012 Congrats.....................Storm Key NIALL BRENNAN STABLES, AGENT I Barn 8 39 ................................. ......b. c................2012 Blame .........................Winnowing NIALL BRENNAN STABLES, AGENT II Barn 8 95 ................................. ......b. c................2012 Distorted Humor ........Captive Melody NIALL BRENNAN STABLES, AGENT III Barn 8 45 ................................. ......gr/ro. f............2012 Congrats.....................Zee Zee 161 ................................. ......dk. b./br. f......2012 -

View Catalogue

CONDITIONS OF SALE - Public Auction THE PLACING OF A BID SHALL CONSTITUTE ACCEPTANCE OF THESE CONDITIONS OF SALE BETWEEN BIDDER AND DANIEL F. KELLEHER AUCTIONS, LLC (“KELLEHER”) BIDDING WIRING INSTUCTIONS: 1. Unless announced otherwise by the auctioneer, all bids are per lot, as numbered in the Please contact us for our wiring instructions. printed Catalogue. Kelleher, as agent for the consignor or vendor, shall regulate the bidding EXHIBITION AND INSPECTION OF LOTS; QUALITY AND AUTHENTICITY and shall determine the manner in which the bidding shall be conducted. Kelleher reserves 7. (a) See viewing schedule for on-premises viewing. Ample opportunity is given for on the right to withdraw any lot prior to sale (without liability to any potential purchaser or premises inspection prior to the auction date, and, upon written request and at Kelleher agent), to re-offer any withdrawn lot, to divide a lot or to group two or more lots belonging discretion. Live video viewing is also available, please contact our offices to arrange to the same consignor or vendor, and to refuse any bid believed not made in good faith. same. Estimates of sales prices contained in the printed Catalogue reflect the best judgment of (b) Each lot is sold as genuine and correctly described, based on individual description Kelleher and are not minimum or upset prices. as modified by any specific notations in this Catalogue. 2. (a) Bids shall be made in the steps set forth on the bidding page (ii). (b) The highest bid (c) Quality. Any lot which a purchaser considers to be incorrectly described may be acknowledged by the auctioneer shall prevail. -

Asian American Feminist Antibodies

ASIANASIAN AMERICANAMERICAN FEMINISTFEMINIST ANTIBODIESANTIBODIES {care in the time of coronavirus} AN ASIAN AMERICAN FEMINIST COLLECTIVE & BLUESTOCKINGS NYC TABLE OF CONTENTS COLLAB INTRODUCTION | Editorial Team 3 WITH LOVE, FROM THE END OF THE WORLD | Kai Cheng Thom 4 HISTORIES: PUBLIC HEALTH & XENOPHOBIC RACISM | Editorial Team 5-6 FIELD NOTES: STATE FAILURES | Matilda Sabal & Salonee Bhaman 7-8 CORONAVIRUS & YELLOW PERIL | Amanda Yee 9 ART: RACISM SPREADS FASTER | Ren Fernandez-Kim (@corpusren) 10 CRIPPING THE APOCALYPSE | Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha 11 LANGUAGE JUSTICE PLATFORM | Shahana Hanif 12-13 JAILS MAKE PEOPLE SICK | Jose Saldana, Komrade Z, and Nadja Guyot 14 RACISM THAT BRIDGES | Kim Tran 15 FRAMEWORKS WHITE DOCTOR | Alison Roh Park 16 PROTECT CAREGIVERS | Ai-jen Poo & NDWA 17 REPRODUCTIVE HEALTH QUESTIONS, ANSWERED | Rewire.News 18 RESOURCES FOR GENDER-BASED VIOLENCE | Sakhi 19 SEX WORKERS AID | Tiffany Diane Tso 20 100 MASKS | Guo Jing, Ariel Tan, & Joyce Tan, unCOVer Initiative 21 LEFT IN THE DARK | Sukjong Hong 22 CORONAVIRUS AND THE DISABILITY COMMUNITY | Alice Wong 23 PARTITION | Fatimah Asghar 24 TIRED OF BEING ASIAN | Alice Tsui 25 BEING AN ASIAN MOM AND CORONAVIRUS | Lisa Lim 26 STORIES TEN OF WANDS | Olivia Ahn 27 POV FROM THE FRONT LINES | Charezka Rendorio 28 REFLECTION | Jean Y. Yu 29 ART: ELSEWHERE | Kaitlin Gu 30 REPORTING ON CORONAVIRUS | AAJA 31 ANTI-VIRAL PLANTCESTORS | Layla Feghali 32-33 KNOW YOUR RIGHTS FOR WORKERS | Editorial Team 34 ‘WASH YOUR HANDS’ | Malaka Ghairib and Wanyu Zhang 35 HALF-ASSED -

Executive of the Week: Atlantic Records GM/Senior VP Urban A&R Lanre Gaba

BILLBOARD COUNTRY UPDATE APRIL 13, 2020 | PAGE 4 OF 19 ON THE CHARTS JIM ASKER [email protected] Bulletin SamHunt’s Southside Rules Top Country YOURAlbu DAILYms; BrettENTERTAINMENT Young ‘Catc NEWSh UPDATE’-es Fifth AirplayFEBRUARY 19, 2021 Page 1 of 30 Leader; Travis Denning Makes History INSIDE Executive of the Week: Sam Hunt’s second studio full-length, and first in over five years, Southside sales (up 21%) in the tracking week. On Country Airplay, it hops 18-15 (11.9 mil- (MCA Nashville/Universal• Publishers Music Group Nashville),Atlantic debuts at No. 1 on Billboard Records’s lion audience impressions, GM/Senior up 16%). VP Top CountryQuarterly: Albums Sony chart dated April 18. In its first week (ending April 9), it earnedDrops 46,000 ‘ATV’ equivalent and album units, including 16,000 in album sales, ac- TRY TO ‘CATCH’ UP WITH YOUNG Brett Youngachieves his fifth consecutive cordingStays to No. Nielsen 1 On Music/MRCSongs Data. Urban A&Rand total Country Lanre Airplay No. 1 as “Catch”Gaba (Big Machine Label Group) ascends SouthsideCharts marks Hunt’s second No. 1 on the 2-1, increasing 13% to 36.6 million impressions. chart and fourth top 10. It follows freshman LP BY DAN RYS Young’s first of six chart entries, “Sleep With- Montevallo• Can You, which Tour arrived in a at the summit in No - out You,” reached No. 2 in December 2016. He Land Down Under? vember 2014 and reigned for nineThis weeks. week, To date, Atlantic Records celebrated two significant now — songsfollowed that come with inthe and multiweek out of playlistsNo. -

Underrated & Misunderstood

05–06 Tools Spotify Ad Studio 07–08 Campaigns TikTok, John Legend, Sleepy Tom, Billie Eilish 09–132 Behind The Campaign- Ghetts APRIL 17 2019 sandboxMUSIC MARKETING FOR THE DIGITAL ERA ISSUE 226 UNDERRATED & MISUNDERSTOOD what people just don’t “get” about digital marketing Sandbox Summit 2019 NYC After the huge success of last year’s inaugural Sandbox Summit in the US, Music Ally returns to NYC again next month with the only dedicated marketing conference for the music industry on May 23. Sandbox Summit is an essential forum for cutting edge and creative thinking in music marketing: a day full of practical tips, refreshing discussions and interviews, insightful presentations, and of course, lots of networking. Brought to you in association with Linkfre, we are delighted to also announce our supporting sponsors, The Orchard and Vevo. Some of the program we have in store for you includes: • FlighthouseSandbox TikTok channel Summitfounder Jacob Pace is on marketing to Gen Z, and Sony Music’sa music Jose marketing Abreu discussing conference how to target Superfans. • Secretly Group’s Robby Morris and Laura Sykes explain the secrets behind the Khruangbin campaignseries which organised included a Spotify by playlist that tapped into Flight APIs • ‘Dry StreamsMusic Paradox’ Ally, panel the with global Pandora’s leader Heather in Ellis, Island Records’ Cindy James, Artist Manager Naveed Hassan (MDDN)digital and The Orchard’smarketing Amanda training Suriani for • Panel on how to bring together the various data silos around an artist hosted by Linkfre’s Jeppethe Faurfelt music industry • International marketingand the panel publisher focused on India, of the China and the African markets AT THE • Podcasting anddigital music panel marketing-focused chaired by Cherie Hu, featuring Atlantic Records’ podcast guru Tom MullenSandbox and KevinReports. -

THE ASMSU November 5, 2009 • Vol

THE ASMSU November 5, 2009 • Vol. 104, Issue 10 ANNUAL SKI SWAP TO SUPPORT BRIDGER YOUTH PROGRAMS 6 l "HATE-FREE BOZONE" BOZONE RESPONDS TO WHITE SUPREMACISTS GOLF PACKS UP THE CLUBS AND BASKETBALL TIPS OFF 13 2 THE ASMSU EXPONENT I NOV. 5, za lllCIT LETTERS FOITMllvs. Welcome to your MSU Dear Editor, The worst part of all is that the sit SAC•EllTO I am writing today on behalf of the ation will get much worse before getti students and faculty that park in the F better. With more snow and/or rain, t STATE (dirt) parking lot. As the fall weather potholes will get bigger and more n hits Bozeman, the seasonal destruction merous. I propose the lot be graded of the dirt lot has commenced. Potholes some manner to restore the conditic develop, then deepen, then deepen This should be a small job, and I thiru some more. This year seems to be par is well worth the effort. ticularly bad, to the point that in some places the lot is nearly impassable. This I know those ofus that park in the d is not (much) of an exaggeration. I have lot don't pay as much, but tl\at does a fairly high clearance 4X4 vehicle, and mean that we don't deserve some ba I don't think a smaller car's suspension maintenance to allow for continued l can handle some of the more crater-like of the lot. areas. n-asthead THIS ISSUE BROUGHT TO YOU BY: MANAGEMENT EDITORIAL ADVISOR NEWS EDITOR Bill Wilke Eric Dietrich EDITOR-IN-CHIEF STATIC EDITOR Brandon French Lisa Lundgren PRODUCTION MANAGER DISTRACTIONS EDITOR Claire Nelson Ben Miller ART DEPARTMENT ATHLETICS EDITOR PHOTOGRAPHER Erica Killham Bruce Muhlbradt OUTDOORS EDITOR GRAPHIC DESIGN Daniel Cassidy Todd Schilling, Andreas Welch COPY EDITOR ADVERTISING & BUSJNESS Jill Searson AD SALES MANAGER Jake Lewendal CONTRIBUTORS Ashley Wheeler, Brent Zundel, r AD SALES REPRESENTATIVES Howard, Trudi Mingus, Kyle Reyne James Rota, Ashley Lewis, Nathan Carroll, Joe Thiel, Josh Fre: Catherine Boberg, Sabre Moore Amy Lanzendorf, Mary Biehl, Jos Wirtz, Derek Brouwer, Nate Cox.