View Was Provided by the National Endowment for the Arts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Manatee PIANO MUSIC of the Manatee BERNARD

The Manatee PIANO MUSIC OF The Manatee BERNARD HOFFER TROY1765 PIANO MUSIC OF Seven Preludes for Piano (1975) 15 The Manatee [2:36] 16 Stridin’ Thru The Olde Towne 1 Prelude [2:40] 2 Cello [2:47] During Prohibition In Search Of A Drink [2:42] 3 All Over The Piano [1:21] Randall Hodgkinson, piano 4 Ships Passing [4:12] (2014) BERNARD HOFFER 5 Prelude [1:24] Events & Excursions for Two Pianos 6 Calypso [3:52] 17 Big Bang Theory [3:15] 7 Franz Liszt Plays Ragtime [3:28] 18 Running [3:19] Randall Hodgkinson, piano 19 Wexford Noon [2:29] 20 Reverberations [3:12] Nine New Preludes for Piano (2016) 21 On The I-93 [2:23] Randall Hodgkinson & Leslie Amper, pianos 8 Undulating Phantoms [1:08] BERNARD HOFFER 9 A Walk In The Park [2:39] 10 Speed Chess [2:17] 22 Naked (2010) [5:05] Randall Hodgkinson, piano 11 Valse Sentimental [3:30] 12 Rabbits [1:06] Total Time = 60:03 13 Spirals [1:40] 14 Canon Inverso [1:44] PIANO MUSIC OF TROY1765 WWW.ALBANYRECORDS.COM TROY1765 ALBANY RECORDS U.S. 915 BROADWAY, ALBANY, NY 12207 TEL: 518.436.8814 FAX: 518.436.0643 ALBANY RECORDS U.K. BOX 137, KENDAL, CUMBRIA LA8 0XD TEL: 01539 824008 © 2019 ALBANY RECORDS MADE IN THE USA DDD WARNING: COPYRIGHT SUBSISTS IN ALL RECORDINGS ISSUED UNDER THIS LABEL. The Manatee PIANO MUSIC OF The Manatee BERNARD HOFFER WWW.ALBANYRECORDS.COM TROY1765 ALBANY RECORDS U.S. 915 BROADWAY, ALBANY, NY 12207 TEL: 518.436.8814 FAX: 518.436.0643 ALBANY RECORDS U.K. -

Victory and Sorrow: the Music & Life of Booker Little

ii VICTORY AND SORROW: THE MUSIC & LIFE OF BOOKER LITTLE by DYLAN LAGAMMA A Dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-Newark Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Graduate Program in Jazz History & Research written under the direction of Henry Martin and approved by _________________________ _________________________ Newark, New Jersey October 2017 i ©2017 Dylan LaGamma ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION VICTORY AND SORROW: THE MUSICAL LIFE OF BOOKER LITTLE BY DYLAN LAGAMMA Dissertation Director: Henry Martin Booker Little, a masterful trumpeter and composer, passed away in 1961 at the age of twenty-three. Little's untimely death, and still yet extensive recording career,1 presents yet another example of early passing among innovative and influential trumpeters. Like Clifford Brown before him, Theodore “Fats” Navarro before him, Little's death left a gap the in jazz world as both a sophisticated technician and an inspiring composer. However, unlike his predecessors Little is hardly – if ever – mentioned in jazz texts and classrooms. His influence is all but non-existent except to those who have researched his work. More than likely he is the victim of too early a death: Brown passed away at twenty-five and Navarro, twenty-six. Bob Cranshaw, who is present on Little's first recording,2 remarks, “Nobody got a chance to really experience [him]...very few remember him because nobody got a chance to really hear him or see him.”3 Given this, and his later work with more avant-garde and dissonant harmonic/melodic structure as a writing partner with Eric Dolphy, it is no wonder that his remembered career has followed more the path of James P. -

Jimmy Raney Thesis: Blurring the Barlines By: Zachary Streeter

Jimmy Raney Thesis: Blurring the Barlines By: Zachary Streeter A Thesis submitted to the Graduate School-Newark Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Jazz History and Research Graduate Program in Arts written under the direction of Dr. Lewis Porter and Dr. Henry Martin And approved by Newark, New Jersey May 2016 ©2016 Zachary Streeter ALL RIGHT RESERVED ABSTRACT Jimmy Raney Thesis: Blurring the Barlines By: Zach Streeter Thesis Director: Dr. Lewis Porter Despite the institutionalization of jazz music, and the large output of academic activity surrounding the music’s history, one is hard pressed to discover any information on the late jazz guitarist Jimmy Raney or the legacy Jimmy Raney left on the instrument. Guitar, often times, in the history of jazz has been regulated to the role of the rhythm section, if the guitar is involved at all. While the scope of the guitar throughout the history of jazz is not the subject matter of this thesis, the aim is to present, or bring to light Jimmy Raney, a jazz guitarist who I believe, while not the first, may have been among the first to pioneer and challenge these conventions. I have researched Jimmy Raney’s background, and interviewed two people who knew Jimmy Raney: his son, Jon Raney, and record producer Don Schlitten. These two individuals provide a beneficial contrast as one knew Jimmy Raney quite personally, and the other knew Jimmy Raney from a business perspective, creating a greater frame of reference when attempting to piece together Jimmy Raney. -

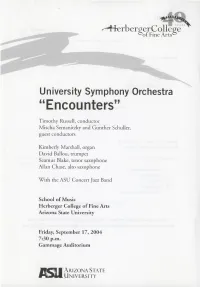

University Symphony Orchestra "Encounters"

FierbergerCollegeYEARS of Fine Arts University Symphony Orchestra "Encounters" Timothy Russell, conductor Mischa Semanitzky and Gunther Schuller, guest conductors Kimberly Marshall, organ David Ballou, trumpet Seamus Blake, tenor saxophone Allan Chase, alto saxophone With the ASU Concert Jazz Band School of Music Herberger College of Fine Arts Arizona State University Friday, September 17, 2004 7:30 p.m. Gammage Auditorium ARIZONA STATE M UNIVERSITY Program Overture to Nabucco Giuseppe Verdi (1813 — 1901) Timothy Russell, conductor Symphony No. 3 (Symphony — Poem) Aram ifyich Khachaturian (1903 — 1978) Allegro moderato, maestoso Allegro Andante sostenuto Maestoso — Tempo I (played without pause) Kimberly Marshall, organ Mischa Semanitzky, conductor Intermission Remarks by Dean J. Robert Wills Remarks by Gunther Schuller Encounters (2003) Gunther Schuller (b.1925) I. Tempo moderato II. Quasi Presto III. Adagio IV. Misterioso (played without pause) Gunther Schuller, conductor *Out of respect for the performers and those audience members around you, please turn all beepers, cell phones and watches to their silent mode. Thank you. Program Notes Symphony No. 3 – Aram Il'yich Khachaturian In November 1953, Aram Khachaturian acted on the encouraging signs of a cultural thaw following the death of Stalin six months earlier and wrote an article for the magazine Sovetskaya Muzika pleading for greater creative freedom. The way forward, he wrote, would have to be without the bureaucratic interference that had marred the creative efforts of previous years. How often in the past, he continues, 'have we listened to "monumental" works...that amounted to nothing but empty prattle by the composer, bolstered up by a contemporary theme announced in descriptive titles.' He was surely thinking of those countless odes to Stalin, Lenin and the Revolution, many of them subdivided into vividly worded sections; and in that respect Khachaturian had been no less guilty than most of his contemporaries. -

Vut 20140303 – Big Bands

JAMU 20140305 – BIG BANDS (2) 10. Chicago Serenade (Eddie Harris) 3:55 Lalo Schifrin Orchestra: Ernie Royal, Bernie Glow, Jimmy Maxwell, Marky Markowitz, Snooky Young, Thad Jones-tp; Billy Byers, Jimmy Cleveland, Urbie Green-tb; Tony Studd-btb; Ray Alonge, Jim Buffington, Earl Chapin, Bill Correa-h; Don Butterfield-tu; Jimmy Smith-org; Kenny Burrell-g; George Duvivier-b; Grady Tate-dr; Phil Kraus-perc; Lalo Schifrin-arr,cond. Englewood Cliffs, NJ, April 27/29, 1964. Verve V6-8587. 11. A Genuine Tong Funeral – The Opening (Carla Bley) 2:14 Gary Burton Quartet with Orchestra: Gary Burton-vib; Larry Coryell-g; Steve Swallow-b; Bobby Moses-dr; Mike Mantler-tp; Jimmy Knepper-tb,btb; Howard Johnson-tu,bs; Leandro “Gato” Barbieri-ts; Steve Lacy-ss; Carla Bley-p,org,cond. New York, July 1967. RCA Victor LSP 3901. 12. Escalator Over the Hill (Carla Bley) 4:57 Michael Mantler-tp; Sam Burtis, Jimmy Knepper, Roswell Rudd-tb; Jack Jeffers-btb; Bob Carlisle, Sharon Freeman-h; John Buckingham-tu; Jimmy Lyons-as; Gato Barbieri-ts; Chris Woods-bs; Perry Robinson-cl; Nancy Newton-vla; Charlie Haden-b; Paul Motian-dr; Tod Papageorge, Bob Stewart, Rosalind Hupp, Karen Mantler, Jack Jeffers, Howard Johnson, Timothy Marquand, Jane Blackstone, Sheila Jordan, Phyllis Schneider, Pat Stewart-voc; Bill Leonard, Don Preston, Viva, Carla Bley- narrators. November 1968-June 1971, various places. JCOA 839310-2. 13. Adventures in Time – 3x3x2x2x2=72 (Johnny Richards) 4:29 Stan Kenton Orchestra: Dalton Smith, Bob Behrendt, Marvin Stamm, Keith Lamotte, Gary Slavo- tp; Bob Fitzpatrick, Bud Parker, Tom Ringo-tb; Jim Amlotte-btb; Ray Starlihg, Dwight Carver, Lou Gasca, Joe Burnett-mell; Dave Wheeler-tu,btb; Gabe Baltazar-as, Don Menza, Ray Florian-ts; Allan Beutler-bs; Joel Kaye-bass,bs; Stan Kenton-p; Bucky Calabrese-b; Dee Barton-dr; Steve Dweck- tympani,perc. -

The Solo Style of Jazz Clarinetist Johnny Dodds: 1923 – 1938

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2003 The solo ts yle of jazz clarinetist Johnny Dodds: 1923 - 1938 Patricia A. Martin Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Martin, Patricia A., "The os lo style of jazz clarinetist Johnny Dodds: 1923 - 1938" (2003). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 1948. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/1948 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. THE SOLO STYLE OF JAZZ CLARINETIST JOHNNY DODDS: 1923 – 1938 A Monograph Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College In partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music By Patricia A.Martin B.M., Eastman School of Music, 1984 M.M., Michigan State University, 1990 May 2003 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This is dedicated to my father and mother for their unfailing love and support. This would not have been possible without my father, a retired dentist and jazz enthusiast, who infected me with his love of the art form and led me to discover some of the great jazz clarinetists. In addition I would like to thank Dr. William Grimes, Dr. Wallace McKenzie, Dr. Willis Delony, Associate Professor Steve Cohen and Dr. -

Big Band Arrangers of the Swing Era Selected List

Big Band Arrangers of the Swing Era Selected list Band leader Arrangers Tex Beneke Henry Mancini Jimmy Dorsey Tutti Camarata Sonny Burke Tommy Dorsey Paul Weston Sy Oliver Axel Stordahl Benny Goodman Eddie Sauter Buster Harding Fletcher Henderson Horace Heidt Frank DeVol Woody Herman Heil Hefti Ralph Burns Igor Stravinsky Harry James Leroy Holmes Dave Mathews Isham Jones Gordon Jenkins Hal Kemp John Scott Trotter Elliot Lawrence Gerry Mulligan Ray McKinley Eddie Sauter Red Norvo Eddie Sauter Artie Shaw Ray Conniff Johnny Mandel Buster Harding Charlie Spivak Nelson Riddle Claude Thornhill Gil Evans Leader/Arranger Arranger Count Basie Buster Smith Jimmy Mundy Andy Gibson Herschel Evans Cab Calloway Foots Thomas Harry White Duke Ellington Billy Strayhorn Earl Hines Jimmy Mundy Budd Johnson Stan Kenton Pete Rugolo Bill Holman Andy Kirk Mary Lou Williams Earl Thompson Glen Miller Bill Finegan Billy May Claude Thornhill Gil Evans Bill Borden Gerry Mulligan Chick Webb Edgar Sampson Charlie Dixon Andy Gibson Herschel Evans Leader/Arranger Les Brown Benny Carter Larry Clinton Will Hudson Elliot Lawrence Russ Morgan Ray Noble Boyd Raeburn Raymond Scott Musicians in Bands that were Important Arrangers Leader Arranger Instrument Bob Crosby Bob Haggart bass Matty Matlock saxophone Deane Kincaide saxophone Jimmy Dorsey Tutti Camarata trumpet Joe Lipman piano Woody Herman Heil Hefti trumpet Ralph Burns piano Hal Kemp John Scott Trotter piano Gene Krupa Gerry Mulligan saxophone Jimmy Lunceford Sy Oliver trumpet Glen Miller Henry Mancini piano Artie Shaw Ray Conniff trombone Johnny Mandel trombone Charlie Spivak Nelson Riddle trombone . -

Jazz and the Cultural Transformation of America in the 1920S

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2003 Jazz and the cultural transformation of America in the 1920s Courtney Patterson Carney Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Carney, Courtney Patterson, "Jazz and the cultural transformation of America in the 1920s" (2003). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 176. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/176 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. JAZZ AND THE CULTURAL TRANSFORMATION OF AMERICA IN THE 1920S A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of History by Courtney Patterson Carney B.A., Baylor University, 1996 M.A., Louisiana State University, 1998 December 2003 For Big ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The real truth about it is no one gets it right The real truth about it is we’re all supposed to try1 Over the course of the last few years I have been in contact with a long list of people, many of whom have had some impact on this dissertation. At the University of Chicago, Deborah Gillaspie and Ray Gadke helped immensely by guiding me through the Chicago Jazz Archive. -

![Eric Dolphy Collection [Finding Aid]. Library of Congress](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6248/eric-dolphy-collection-finding-aid-library-of-congress-226248.webp)

Eric Dolphy Collection [Finding Aid]. Library of Congress

Eric Dolphy Collection Guides to Special Collections in the Music Division of the Library of Congress Music Division, Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 2014 Contact information: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.music/perform.contact Additional search options available at: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.music/eadmus.mu014006 LC Online Catalog record: http://lccn.loc.gov/2014565637 Processed by the Music Division of the Library of Congress Collection Summary Title: Eric Dolphy Collection Span Dates: 1939-1964 Bulk Dates: (bulk 1960-1964) Call No.: ML31.D67 Creator: Dolphy, Eric Extent: Approximately 250 items ; 6 containers ; 5.0 linear feet Language: Collection material in English Location: Music Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Summary: Eric Dolphy was an American jazz alto saxophonist, flautist, and bass clarinetist. The collection consists of manuscript scores, sketches, parts, and lead sheets for works composed by Dolphy and others. Selected Search Terms The following terms have been used to index the description of this collection in the Library's online catalog. They are grouped by name of person or organization, by subject or location, and by occupation and listed alphabetically therein. People Dolphy, Eric--Manuscripts. Dolphy, Eric. Dolphy, Eric. Dolphy, Eric. Works. Selections. Mingus, Charles, 1922-1979. Works. Selections. Schuller, Gunther. Works. Selections. Subjects Composers--United States. Jazz musicians--United States. Jazz--Lead sheets. Jazz. Music--Manuscripts--United States. Saxophonists--United States. Form/Genre Scores. Administrative Information Provenance Gift, James Newton, 2014. Accruals No further accruals are expected. Processing History The Eric Dolphy Collection was processed by Thomas Barrick in 2014. Thomas Barrick coded the finding aid for EAD format in October 2014. -

Gerry Mulligan Discography

GERRY MULLIGAN DISCOGRAPHY GERRY MULLIGAN RECORDINGS, CONCERTS AND WHEREABOUTS by Gérard Dugelay, France and Kenneth Hallqvist, Sweden January 2011 Gerry Mulligan DISCOGRAPHY - Recordings, Concerts and Whereabouts by Gérard Dugelay & Kenneth Hallqvist - page No. 1 PREFACE BY GERARD DUGELAY I fell in love when I was younger I was a young jazz fan, when I discovered the music of Gerry Mulligan through a birthday gift from my father. This album was “Gerry Mulligan & Astor Piazzolla”. But it was through “Song for Strayhorn” (Carnegie Hall concert CTI album) I fell in love with the music of Gerry Mulligan. My impressions were: “How great this man is to be able to compose so nicely!, to improvise so marvellously! and to give us such feelings!” Step by step my interest for the music increased I bought regularly his albums and I became crazy from the Concert Jazz Band LPs. Then I appreciated the pianoless Quartets with Bob Brookmeyer (The Pleyel Concerts, which are easily available in France) and with Chet Baker. Just married with Danielle, I spent some days of our honey moon at Antwerp (Belgium) and I had the chance to see the Gerry Mulligan Orchestra in concert. After the concert my wife said: “During some songs I had lost you, you were with the music of Gerry Mulligan!!!” During these 30 years of travel in the music of Jeru, I bought many bootleg albums. One was very important, because it gave me a new direction in my passion: the discographical part. This was the album “Gerry Mulligan – Vol. 2, Live in Stockholm, May 1957”. -

Downbeat.Com March 2014 U.K. £3.50

£3.50 £3.50 U.K. DOWNBEAT.COM MARCH 2014 D O W N B E AT DIANNE REEVES /// LOU DONALDSON /// GEORGE COLLIGAN /// CRAIG HANDY /// JAZZ CAMP GUIDE MARCH 2014 March 2014 VOLUME 81 / NUMBER 3 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Associate Editor Davis Inman Contributing Editor Ed Enright Designer Ara Tirado Bookkeeper Margaret Stevens Circulation Manager Sue Mahal Circulation Assistant Evelyn Oakes Editorial Intern Kathleen Costanza Design Intern LoriAnne Nelson ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Pete Fenech 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank- John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene -

Jazz in America • the National Jazz Curriculum Test Bank 7 - Avant Garde/Free Jazz and Fusion Select the BEST Answer

Jazz in America • The National Jazz Curriculum Test Bank 7 - Avant Garde/Free Jazz and Fusion Select the BEST answer 1. Free Jazz was a reaction to A. Dixieland B. the yuppies of the 1980s C. the women’s movement D. Rock 'n Roll E. Swing, Cool Jazz, and Hard Bop 2. Free Jazz improvisation was generally A. not predetermined B. easy to listen to C. based on predetermined chord progressions D. based on the Blues E. simple 3. Free Jazz musicians freed themselves by improvising A. for at least three standard choruses B. solely on the emotions of the moment C. ala Kenny G D. infrequently E. according to the composer’s intentions 4. In Free Jazz, traditional values of melody, harmony, and rhythm were A. referred to continually B. used to build the form of a tune C. discarded D. important E. always in the soloist's mind 5. Free Jazz is most closely related to A. the homeless B. improvised 20th century classical and world music C. Rock ‘n Roll D. Funk E. inexpensive jazz 6. Free Jazz allowed for the exploration of A. tonal colors and harmonies B. traditional ways to play Swing C. ideas on how to make jazz more traditional D. ideas on how to make jazz more audience accessible E. expensive jazz 7. Free Jazz A. was highly regarded by all B. pushed the limits of what musicians could play and what audiences could accept C. was popular among musicians D. became the most popular jazz style in the late 1950’s and ‘60s E.