Download This PDF File

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alumni Message from Principal Solomon in THIS NEWSLETTER

Rev. Dr. Davidsathananthan Solomon, Principal Jaffna College [email protected] Volume 1, Issue 1, 2017 IN THIS NEWSLETTER Chairperson Jaffna College Board Alumni Message from Principal Solomon Editor’s Greetings College Students Perform Well in Examinations Upgrade to Daniel Poor Library New Junior Vice Principal English Language Resources A Generous Gift for Physical Education Starting an English Laboratory WELCOME TO “STEPPING UP’ FROM THE CHAIR OF THE BOARD On behalf of the Jaffna College Board of Directors, welcome to this first E-newsletter for our College Alumni, Stepping Up. I congratulate Principal Solomon and Junior Vice-Principal Gladys Muthurajah for their initiative in starting Stepping Up. Their initiative has stepped up to the Board’s challenge to implement a new policy of stakeholder engagement with our Alumni. The Board has recently carried out an extensive review of our governance performance. Following best practice advice specifically for governance development in low-income nations like Sri Lanka, we have adopted a policy to improve our relationships with stakeholders. The Board is committed to work together with Alumni for the benefit of Jaffna College students and staff. I second the Principal’s invitation to you to visit the College. I am continually delighted when Alumni visit me to discuss the College’s development, how they might contribute, and express their interest in better understanding the Board’s role and responsibilities. The Board is committed to better informing you of our work, and looks forward to receiving your feedback. Board minutes are available to you in the Principal’s office, for your information. As a Board, we have been stepping up to meet the challenges facing us. -

APL Details Unclaimed Unpaid Interim Dividend F.Y. 2019-2020

ALEMBIC PHARMACEUTICALS LIMITED STATEMENT OF UNCLAIMED/UNPAID INTERIM DIVIDEND FOR THE YEAR 2019‐20 AS ON 6TH APRIL, 2020 (I.E. DATE OF TRANSFER TO UNPAID DIVIDEND ACCOUNT) NAME ADDRESS AMOUNT OF UNPAID DIVIDEND (RS.) MUKESH SHUKLA LIC CBO‐3 KA SAMNE, DR. MAJAM GALI, BHAGAT 200.00 COLONEY, JABALPUR, 0 HAMEED A P . ALUMPARAMBIL HOUSE, P O KURANHIYOOR, VIA 900.00 CHAVAKKAD, TRICHUR, 0 RAJESH BHAGWATI JHAVERI 30 B AMITA 2ND FLOOR, JAYBHARAT SOCIETY 3RD ROAD, 750.00 KHAR WEST MUMBAI 400521, , 0 NALINI NATARAJAN FLAT NO‐1 ANANT APTS, 124/4B NEAR FILM INSTITUTE, 1000.00 ERANDAWANE PUNE 410004, , 0 ANURADHA SEN C K SEN ROAD, AGARPARA, 24 PGS (N) 743177, , 0 900.00 SWAPAN CHAKRABORTY M/S MODERN SALES AGENCY, 65A CENTRAL RD P O 900.00 NONACHANDANPUKUR, BANACKPUR 743102, , 0 PULAK KUMAR BHOWMICK 95 HARISHABHA ROAD, P O NONACHANDANPUKUR, 900.00 BARRACKPUR 743102, , 0 JOJI MATHEW SACHIN MEDICALS, I C O JUNCTION, PERUNNA P O, 1000.00 CHANGANACHERRY, KERALA, 100000 MAHESH KUMAR GUPTA 4902/88, DARYA GANJ, , NEW DELHI, 110002 250.00 M P SINGH UJJWAL LTD SHASHI BUILDING, 4/18 ASAF ALI ROAD, NEW 900.00 DELHI 110002, NEW DELHI, 110002 KOTA UMA SARMA D‐II/53 KAKA NAGAR, NEW DELHI INDIA 110003, , NEW 500.00 DELHI, 110003 MITHUN SECURITIES PVT LTD 1224/5 1ST FLOOR SUCHET CHAMBS, NAIWALA BANK 50.00 STREET, KAROL BAGH, NEW DELHI, 110005 ATUL GUPTA K‐2,GROUND FLOOR, MODEL TOWN, DELHI, DELHI, 1000.00 110009 BHAGRANI B‐521 SUDERSHAN PARK, MOTI NAGAR, NEW DELHI 1350.00 110015, NEW DELHI, 110015 VENIRAM J SHARMA G 15/1 NO 8 RAVI BROS, NR MOTHER DAIRY, MALVIYA 50.00 -

American Ceylon Mission

, RE:p~·a·R T , "", .I.:.~ OF THE '.(. .~, ... AMERICAN CEYLON MISSION . .. "', FOR 1852. PUBLISHED Xli 1849. I;:,: . » •. "":. .~. REPORT OF THE A~IERICAN CEYLON MISSION, FOR THE YEAR 1852. 3}affna: AMERICAN MISSION PRESS-To S. BURNELL, PRINTER. Hl53. REPORT ALTHOUGH we have not been in the habit of publishing an annual report of our labors, we find an occasional review of the way in which the Lord has led us, profitable to ourselves and encouraging to those who feel an interest in the establishment of Christ's kingdom in this land. As it is now several years since such a review was taken, the following report of the operations of the past year, will contain a more extended statement of the state and progress of the work than would otherwise be necessary. Missionaries and Stations. Though we have been favored by the accession of Mr. and Mrs. Sanders to our number during the year,. yet the absence of others on account of ill-health has prevented the occupancy of vacant stations. Chavagacherry has been vacant during a part of the year by tke absence of Mr. and Mrs. Noyes on a visit to the continent. As the clima te in that region seems more favorable to the health of Mrs. Noyes, they now contemplate a permanent removal to the Madura Mission. Mr. and Mrs. Mills left for Madras in August, on account of her feeble health, expecting to be obliged to proceed to Amer ica. After a reside~ce of several months in Madras, they have been enabled to return to us, and resume their duties in con nection with the Seminary, and Mr. -

Slavery and Caste Supremacy in the American Ceylon Mission

Article CASTE: A Global Journal on Social Exclusion Vol. 1, No. 1, pp. 155–174 February 2020 brandeis.edu/j-caste ISSN 2639-4928 DOI: 10.26812/caste.v1i1.117 In Nāki’s Wake: Slavery and Caste Supremacy in the American Ceylon Mission Mark E. Balmforth1 (Bluestone Rising Scholar Honorable Mention 2019) Abstract In 1832, a woman named Caṅkari Nāki died in Ceylon, and her descendants have been haunted by a curse ever since. One of the first converts of the American Ceylon Mission, Nāki was part of an enslaved caste community unique to the island, and one of the few oppressed-caste members of the mission. The circumstances of her death are unclear; the missionary archive is silent on an event that one can presume would have affected the small Christian community, while the family narrative passed through generations is that Nāki was murdered by members of the locally dominant Vellalar caste after marrying one of their own. In response to this archival erasure, this essay draws on historical methods developed by Saidiya Hartman and Gaiutra Bahadur to be accountable to enslaved and indentured lives and, in Hartman’s words, to ‘make visible the production of disposable lives.’ These methods actively question what we can know from the archives of an oppressor and, for this essay, enable a reading of Nāki’s life at the centre of a mission struggling over how to approach caste. Nāki’s story, I argue, helps reveal an underexplored aspect of the interrelationship between caste and slavery in South Asia, and underlines the value of considering South Asian slave narratives as source material into historiographically- and archivally-obscured aspects of dominant caste identity. -

Professional-Address.Pdf

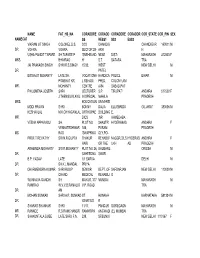

NAME FAT_HS_NA CORADDRE CORADD CORADDRE CORADDR COR_STATE COR_PIN SEX NAMECAT SS RESS1 SS2 ESS3 VIKRAM JIT SINGH COLONEL D.S. 3/33 CHANDIG CHANDIGAR 160011 M DR. VOHRA VOHRA SECTOR 28- ARH H USHA PANDIT TAPARE SH.TAPARE P 'SNEHBAND NEAR DIST- MAHARASH 412803 F MRS. BHIMRAO H' S.T. SATARA TRA JAI PRAKASH SINGH SHRI R.S.SINGH 15/32, WEST NEW DELHI M DR. PATEL BISWAJIT MOHANTY LATE SH. VOCATIONA HANDICA POLICE BIHAR M PRABHAT KR. L REHABI. PPED, COLONY,ANI MR. MOHANTY CENTRE A/84 SABAD,PAT PHILOMENA JOSEPH SHRI LECTURER S.P. TIRUPATI ANDHRA 517502 F J.THENGUVILAYIL IN SPECIAL MAHILA PRADESH MRS. EDUCATION UNIVERSI MODI PRAVIN SHRI BONNY DALIA ELLISBRIDG GUJARAT 380006 M KESHAVLAL M.K.CHHAGANLAL ORTHOPAE BUILDING E, MR. DICS ,NR AHMEDABA VEENA APPARASU SH. PLOT NO SHASTRI HYDERABAD ANDHRA F VENKATESHWAR 188, PURAM PRADESH MS. RAO 'SWAPRIKA' CLY,PO- PROF.T REVATHY SRI N.R.GUPTA THAKUR REHABI.F NAGGR,DILS HYDERAB ANDHRA F HARI OR THE UKH AD PRADESH ARABINDA MOHANTY SRI R.MOHANTY PLOT NO 24, BHUBANE ORISSA M DR. SAHEEDNA SWAR B.P. YADAV LATE 1/1 SARVA DELHI M DR. SH.K.L.MANDAL PRIYA DHARMENDRA KUMAR SHRI ROOP SENIOR DEPT. OF SAFDARJAN NEW DELHI 110029 M DR. CHAND MEDICAL REHABILI G WUNNAVA GANDHI SH MAYUR, 377 MUMBAI MAHARASH M RAMRAO W.V.V.B.RAMALIG V.P. ROAD TRA DR. AM MOHAN SUNKAD SHRI A.R. SUNKAD ST. HONAVA KARNATAKA 581334 M DR. IGNATIUS R SHARAS SHANKAR SHRI 11/17, PANDUR GOREGAON MAHARASH M MR. RANADE R.S.RAMCHANDR RAMKRIPA ANGWADI (E), MUMBAI TRA DR. -

St. John's Began with Just Seven Students by Professor S

St. John's Began with just seven students By Professor S. Ratnajeevan H. Hoole (Extracted from The Sunday Leader, April 5, 1998) This year St. John's celebrates its 175th anniversary. The dynamic enterprise that is St. John's must be judged in light of the motivation and dedication of its founders, who were determined to serve selflessly what must surely have been a strange people in a strange land. The early years of the 19th century saw the expansion of Christian missions in the British colonies. Colonial administrative officials, with their eye on profit, wanted good relations with the locals and had forbidden any Christian evangelical work and refused to employ those locals who had taken up the Christian faith. In the first year of British rule alone, 300 new Hindu temples were built in Jaffna by the British. Indeed, the antagonism to Christianity in the 20 year lull between the British take-over and the arrival of the first missionaries saw the number of temples in Jaffna growing 4 fold. The growing evangelical movement in England's Parliament put a stop to this and since 1813 Christian missions started to spread throughout the colonies. Arrival of Rev. Knight This development brought to Sri Lanka the Rev. Joseph Knight (born in Stroud, England, on October 17, 1787) and three others who were given the requisite training and ordained priest just before their departure in the Autumn of 1817 as missionaries of the Church Missionary Society, the CMS. It was a dangerous journey to the East with many a missionary dying or losing a family member before the journey's end. -

<3°SS*)^§@0 & 1&0 O S)Q5

<3 °SS*)^§@0 & 1 & 0 OS )Q5 THE CEYLON GOVERNMENT GAZETTE ff°2S» 1 2 ,1 4 9 — I 9 6 0 gjs£ 2 4 — 2 4 . 6 . 1 9 6 0 No. 12,149— FR ID A Y, JUNE 24, 1960 (Published by Authority) PART V-BOOK LIST, &c. (Separate paging is given to each language of every Part in order that it may he filed eeparately,) Statement of Books Printed in Ceylon and Registered under the Printers and Publishers Ordinance (Cap. 137), as amended by The Printers and Publishers (Amendment) Act, No. 28 of 1951, during the Quarter ended March 31, 1959 CONTRACTIONS : (a) The language in which the book is written ;(b) The name of the author, translator or editor of the book or any part thereof; (c) The subject; (d) The place of printing; (e) The place of publication ; (f) The name or firm of the printer ; (g) The name or firm of the publisher ; (h) The date of issue from the press ; (i) The number of pages ; (j) The size; (k) The first, second or other number of the edition; (1) The number of copies of which the edition consists ; (m) Whether the book is printed or lithographed; (n) The price at which the book is sold to the public ;(o) The name and ■residence of the proprietor of the copyright,or of any portion of the copyright. Quarter ended March 31,1959—First Quarter 1959 GENERAL WORKS GENERAL PERIODICALS 75175 Muthukumarath Thambiran—Ninaivu Malar 75270 Samastha Lanka Welanda Manthrana Sabhawa— (a) Tamil, (b) S. -

The Gazette of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka

YS% ,xld m%cd;dka;s%l iudcjd§ ckrcfha .eiÜ m;%h The Gazette of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka wxl 2"023 – 2017 cqks ui 09 jeks isl=rdod – 2017'06'09 No. 2,023 – FRIDAY, JUNE 09, 2017 (Published by Authority) PART I : SECTION (I) – GENERAL (Separate paging is given to each language of every Part in order that it may be fi led separately) PAGE PAGE Proclamations, &c., by the President … — Government Notifi cations … … 757 Appointments, &c., by the President … 758 Price Control Orders … … — Appointments, &c., by the Cabinet of Ministers … 774 Central Bank of Sri Lanka Notices… … — Accounts of the Government of Sri Lanka … — Appointments, &c., by the Public Service Commission — Revenue and Expenditure Returns… … — Appointments, &c., by the Judicial Service Commission — Miscellaneous Departmental Notices … 834 Other Appointments, &c. … … — Notice to Mariners … … — Appointments, &c., of Registrars … — “Excise Ordinance” Notices … … — Note.– Local Authorities Elections (Amendment) Bill was published as a supplement to the Part II of the Gazette of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka of June 02, 2017. Laila Umma Deen Foundation (Incorporation) Bill was published as a supplement to the Part II of the Gazette of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka of June 02, 2017. IMPORTANT NOTICE REGARDING ACCEPTANCE OF NOTICES FOR PUBLICATION IN THE WEEKLY “GAZETTE” ATTENTION is drawn to the Notifi cation appearing in the 1st week of every month, regarding the latest dates and times of acceptance of Notices for publication in the weekly Gazettes, at the end of every weekly Gazette of Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka. -

EAP835 Survey Reports Anonymous Private Collection 1

EAP835 Survey Reports Anonymous Private Collection 1 Description of materials: Collection 1 consists of ten manuscript volumes produced by the American Ceylon Mission (ACM) between 1815 and 1883. These volumes include reports, church record books, and minutes from ACM meetings, letterbooks, and a volume of advice for the wives of missionaries. Due to their focus on the ACM and authorship by its leading early figures, these volumes are related to the materials held in Collection 2, at the Jaffna Diocese of the Church of South India (JDCSI) in Vaddukoddai, Jaffna. Most of these materials are in fair to poor condition. Survey method: Seven manuscripts were originally shown to EAP835 Programme Managers by a member of the Jaffna Protestant community who is well-known to Manager Mark Balmforth. The Managers immediately noted that the manuscripts are all unique files from the nineteenth-century and therefore digitizable by British Library guidelines. Following this discovery, the Managers were given permission to survey the Private Collector’s home to search for new materials but none were found. Over the course of five months, the Private Collector unearthed three other nineteenth-century manuscript volumes of the same subjects and value as the previous materials. The Collector has noted that they will willingly share with EAP835 any new documents they might come upon in the future. Description of archive: The materials from this collection were not arranged when found. They were lent to EAP835 in a suitcase, in no particular order. When EAP835 finished digitizing the files, they were fumigated, wrapped in red cotton cloth to repel insects, labelled, and returned to the owner along with insect-repellent preservation sachets for proper storage. -

Educational Activities of American Missionaries in Jaffna (17961948)A Historical View

Kandiah Arunthavarajah(1) Educational activities of American Missionaries in Jaffna (17961948)A Historical view (1) Dept.of History, University of Jaffna, Sri Lanka. ([email protected]) Abstract: The reign of British in Jaffna was distinct The research methodology is based on history. from other European powers especially from those of The primary sources for this study include the British Portuguese and Dutch. These distinctions were based documents, notes, letters and books written by the on political, economical and socio cultural levels. priests who had come here to propagate Christianity Jaffna was not an exception for these changes. The in Jaffna and archaeological and other historical period of Portuguese and Dutch made small changes materials. I have utilized as secondary sources, books in the life style of people, whereas the changes made and articles in the journals, magazines and internet during the British reign were remarkable. The main based sources. reason for these changes was the arrival of Christian Key Words: Bahthi Movement, Guru kula education, Missionaries and their services. The American Women education, missions schools Missionaries became more prominent as their services were more public oriented. As a result of this they could also imprint their name in the history of Jaffna. American Missionaries and their The notable period of the impact of the Missionaries arrival in Jaffna was from the 1820s to early 20th century. During this The Bahthi Movement which originated in period they engaged themselves in printing and publishing translations of English works into Tamil. Massachusetts formulated American mission in 1810. Printing publishing and establishment of primary , During their early days they travelled to India, China secondary and tertiary educational Institutions and and Burma to spread Christianity in Oriental provision of health care for residents of the Jaffna countries. -

Nutrition Knowledge on Dietrelated Chronic Non Communicable

A.H.M.Mufas(1), A.H.M.Rifas(2), A.H.L. Fareeza(3) and O.D.A.N.Perera(1) Nutrition knowledge on dietrelated chronic non communicable diseases among the graduates from South Eastern University of Sri Lanka (1) Department of Food Science and Technology, Faculty of Livestock Fisheries and Nutrition, Wayamba University of Sri Lanka, Sri Lanka. ( Email: [email protected]) (2) Department of Islamic studies, Faculties of Islamic Studies and Language, South eastern University of Sri Lanka. (3) Department of Management, Faculty of Management studies and commerce, South eastern University of Sri Lanka. Abstract - The Purpose of this study is to understand of individuals plus households and early retirement, all the nutrition knowledge of the graduates on diet have a great impact on the economic productivity of a related chronic NCDs. A descriptive cross sectional country, bringing about the spiral of ill health and study was undertaken among 200 graduates of south poverty (Abegunde and Stanciole, 2006; Suhrcke et al., eastern university to assess the nutrition knowledge. 2005). Knowledge level analyzed with socio-demographic It has been projected that, by 2020, NCDs will characteristics. Overall knowledge of graduates was account for almost three-quarters of all deaths poor; not a single graduate identified with good worldwide, and that 71% of deaths due to ischemic knowledge. Gender, home area, religious group, heart disease (IHD), 75% of deaths due to stroke, and marital status of the respondents turned out to be not 70% of deaths due to diabetes will occur in developing associated with the knowledge level of the graduates countries (Barker et al, 1993a). -

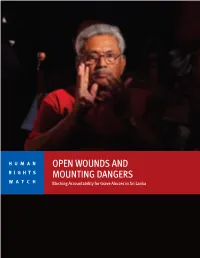

Open Wounds and Mounting Dangers

HUMAN OPEN WOUNDS AND RIGHTS MOUNTING DANGERS WATCH Blocking Accountability for Grave Abuses in Sri Lanka Open Wounds and Mounting Dangers Blocking Accountability for Grave Abuses in Sri Lanka Copyright © 2021 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-62313-887-5 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people worldwide. We scrupulously investigate abuses, expose the facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice. Human Rights Watch is an independent, international organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org FEBRUARY 2021 ISBN: 978-1-62313-887-5 Open Wounds and Mounting Dangers Blocking Accountability for Grave Abuses in Sri Lanka Summary ......................................................................................................................... 1 Silencing Victim’s Families and Critics ......................................................................................4 Conflict-Era Violations and Failure of Accountability ................................................................