Why the Lost Colony Collapsed

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Influence of the Irish Tudor and Stuart Plantation Experiences in the Evolution of American Colonial Theory and Practice

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1992 "This Famous Island in the Virginia Sea": The Influence of the Irish Tudor and Stuart Plantation Experiences in the Evolution of American Colonial Theory and Practice Meaghan Noelle Duff College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Duff, Meaghan Noelle, ""This Famous Island in the Virginia Sea": The Influence of the Irish udorT and Stuart Plantation Experiences in the Evolution of American Colonial Theory and Practice" (1992). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539625771. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-kvrp-3b47 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "THIS FAMOUS ISLAND IN THE VIRGINIA SEA": THE INFLUENCE OF IRISH TUDOR AND STUART PLANTATION EXPERIENCES ON THE EVOLUTION OF AMERICAN COLONIAL THEORY AND PRACTICE A THESIS PRESENTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY THE COLLEGE OF WILLIAM AND MARY IN VIRGINIA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS BY MEAGHAN N. DUFF MAY, 1992 APPROVAL SHEET THIS THESIS IS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS AGHAN N APPROVED, MAY 1992 '''7 ^ ^ THADDEUS W. TATE A m iJI________ JAMES AXTELL CHANDOS M. -

Outdoor Theatre in North Carolina Lagniappe

* Lagniappe *Lagniappe (lan-yap, lan yap ) n. An extra or unexpected gift or benefit. [Louisiana French] William Joseph Thomas, Assistant Director for Collections and Scholarly Communications, Joyner Library, East Carolina University From “The Lost Colony” to “Unto These Hills”: Outdoor Theatre in North Carolina ummertime is high season for outdoor dramas, and North Carolina has a rich history of Sthem. Many NC natives have at- tended a production of “The Lost Colony” in Manteo or “Unto These Hills” in Cherokee. Other outdoor dramas in our state include “Strike at the Wind,” in Pembroke; “Horn in the West,” in Boone; “Tom Dooley: A Wilkes County Legend,” in Wil- kesboro; “First for Freedom,” in Halifax; and “From this Day Forward,” in Valdese. Shakespeare has his place in North Carolina too, from Ashe- ville’s Montford Park Players to Wilm- ington’s Cape Fear Shakespeare. The first, and arguably best-known, of North Carolina’s outdoor dramas is “The Lost Colony.” Written by Pu- litzer prize-winning NC native Paul Figure 1: Andy Griffith in the The Lost Colony, 1950, from Joyner Library Digital Collections, Green to commemorate its 350th an- http://digital.lib.ecu.edu/34133. niversary, “The Lost Colony” tells the story of the intended settlement of Colony” has entertained millions of around Robeson County from 1864 1587 and subsequent disappearance audience members and provided op- to 1872.3 Written by NCCU profes- of the 117 English colonists, includ- portunity for some 5,000 actors, in- sor of drama Randolph Umberger, ing Virginia Dare, first English child cluding favorite North Carolina son “Strike at the Wind” was performed born in the New World.1 Opening Andy Griffith. -

Early Colonial Life

Early Colonial Life The 16th century was the age of mercantilism, an extremely competitive economic philosophy that pushed European nations to acquire as many colonies as they could. As a result, for the most part, the English colonies in North America were business ventures. They provided an outlet for England’s surplus population and more religious freedom than England did, but their primary purpose was to make money for their sponsors. The first English settlement in North America was established in 1587, when a group of colonists (91 men, 17 women and nine children) led by Sir Walter Raleigh settled on the island of Roanoke. Mysteriously, the Roanoke colony had vanished entirely. Historians still do not know what became of its inhabitants. In 1606, King James I divided the Atlantic seaboard in two, giving the southern half to the Virginia Company and the northern half to the Plymouth Company. In 1606, just a few months after James I issued its charter, the London Company sent 144 men to Virginia on three ships: the Godspeed, the Discovery and the Susan Constant. They reached the Chesapeake Bay in the spring of 1607 and headed about 60 miles up the James River, where they built a settlement they called Jamestown. The Jamestown colonists had a rough time of it: They were so busy looking for gold and other exportable resources that they could barely feed themselves. It was not until 1616, when Virginia’s settlers learned to grow tobacco and John Smith’s leadership helped the colony survive. The first African slaves arrived in Virginia in 1619. -

Hclassification

Form No. 10-306 (Rev. 10-74) J, UN1TEDSTATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM FOR FEDERAL PROPERTIES SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS ____________TYPE ALL ENTRIES - COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS___________ | NAME HISTORIC Lane's New Fort in Virginia/Cittie of Raleigh AND/OR COMMON ~ Fort Raleigh National Historic Site ( \\ ^f I____________ LOCATION STREETS.NUMBER North end of Roanoke Island; 1 mile east of William B. Umstead Memorial Bridge on U.S. 64. —NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Manteo — VICINITY OF First STATE CODE COUNTY CODE North Carolina 37 Dare 055 HCLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE —DISTRICT ^.PUBLIC X-OCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM _BUILDING(S) —PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED _ COMMERCIAL 2L.PARK —STRUCTURE _BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS -^.EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE XsiTE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE JCENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _ IN PROCESS —YES. RESTRICTED X.GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED X_YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION —NO —MILITARY —OTHER: [AGENCY REGIONAL HEADQUARTERS: (If applicable) National Park Service. Department of the Interior, Southeast Regional Office STREET 8» NUMBER 1895 Phoenix Boulevard CITY. TOWN STATE Atlanta VICINITY OF Georgia 30349 LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC. Dare County Courthouse/Register of Deeds STREET & NUMBER Courthouse Building CITY, TOWN STATE Manteo North Carolina 27954 TITLE DATE —FEDERAL —STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL CITY. TOWN STATE DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —XEXCELLENT —DETERIORATED —UNALTERED X.ORIGINALSITE —GOOD —RUINS JCALTERED —MOVED DATE- —FAIR —UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The boundaries of Fort Raleigh National Historic Site include 159 acres. However, most of this acreage is either developed area, being managed as a natural area or the Elizabethan Gardens maintained by the Garden Club of North Carolina. -

Fort Raleigh Within the Limits of Present-Day United States, and Local Indian Wars

The scene of earliest English colonizing attempts The colonists' quest for riches involved them in Fort Raleigh within the limits of present-day United States, and local Indian wars. Food became scarce, and day birthplace of the first English child born in the after day they anxiously watched the horizon for NATIONAL HISTORIC SITE . NORTH CAROLINA New World. the returning supply ships. At last sails appeared, and Sir Francis Drake anchored off the inlet. Lane The north end of Roanoke Island is the site of Sir and his men accepted Drake's offer of ships and Walter Raleigh's ill-fated attempts to establish an supplies to explore farther north for a better English community in America. It is our link with harbor. However, the ships were lost the next day the vibrant era of Queen Elizabeth I and the golden in a storm. Weak and discouraged, the entire ex age of the English Rennaissance. a period of pedition decided to return to England with Drake. exploration and expansion when men of vision strove to establish colonies in distant lands to Shortly afterward. Sir Richard Grenville, after benefit the Mother Country. (Spain had already returning to Roanoke with supplies, searched for grown rich and powerful through her colonial em the departed expedition. When he couldn't find pire.) Here on Roanoke Island, England's first it,he settled 15 men on the island with provisions serious attempt to turn her dream of empire into for 2 years. They were to hold the country in the reality ended in failure and the strange disap Queen's name until another colony could be pearance of the colony of 1587. -

The Frontiersman from Lout to Hero Notes on the Significance Ofthe Comparative Method and the Stage Theory in Early American Literature and Cidture

The Frontiersman from Lout to Hero Notes on the Significance ofthe Comparative Method and the Stage Theory in Early American Literature and Cidture J. A. LEO LEMAY XHROUGHOUTTHE seventeenth and most of the eighteenth centuries, the frontiersman was generally regarded as a shift- less outcast, a lout tending to criminality, a villain too lazy or too stupid or too vulgar to exist in society, and a traitor to the culture.1 Long before the concept ofthe frontiersman existed, men who adopted Indian customs were regarded with suspi- cion and fear by their white contemporaries. In Virginia in 1612, Sir Thomas Dale punished those who 'did Runne Away unto the Indjans' in 'A moste severe mannor.' 'Some he apointed to be hanged Some burned Some to be broken upon This paper in a slightly different form was read at the annual meeting ofthe American Antiquarian Society on October 19, 1977. • The only previous work I know that deals specifically with 'the emergence ofthe frontiersman as a heroic figure' is Jules Zanger, 'The Frontiersman in Popular Fiction, 1820-60,' in John F. McDermott, ed.. The Frontier Re-examined (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1967), pp. 141-53, where Zanger claims the heroic frontiersman emerged in response to ( 1 ) the popularity of Sir Walter Scott's Waverley novels; (2) 'the public acclaim won by Jackson's Kentucky rifleman at New Orleans'; (3) the pop- ular images of Daniel Boone and Davy Crockett; and (4) the character of Natty Bumppo in Cooper's Leatherstocking series of novels. All these influences, with the exception of the early fame of Daniel Boone, are later than eighteenth-century, the primary period that I am considering. -

Colonial Failure in the Anglo-North Atlantic World, 1570-1640 (2015)

FINDLEY JR, JAMES WALTER, Ph.D. “Went to Build Castles in the Aire:” Colonial Failure in the Anglo-North Atlantic World, 1570-1640 (2015). Directed by Dr. Phyllis Whitman Hunter. 266pp. This study examines the early phases of Anglo-North American colonization from 1570 to 1640 by employing the lenses of imagination and failure. I argue that English colonial projectors envisioned a North America that existed primarily in their minds – a place filled with marketable and profitable commodities waiting to be extracted. I historicize the imagined profitability of commodities like fish and sassafras, and use the extreme example of the unicorn to highlight and contextualize the unlimited potential that America held in the minds of early-modern projectors. My research on colonial failure encompasses the failure of not just physical colonies, but also the failure to pursue profitable commodities, and the failure to develop successful theories of colonization. After roughly seventy years of experience in America, Anglo projectors reevaluated their modus operandi by studying and drawing lessons from past colonial failure. Projectors learned slowly and marginally, and in some cases, did not seem to learn anything at all. However, the lack of learning the right lessons did not diminish the importance of this early phase of colonization. By exploring the variety, impracticability, and failure of plans for early settlement, this study investigates the persistent search for usefulness of America by Anglo colonial projectors in the face of high rate of -

Where Have All the Indians Gone? Native American Eastern Seaboard Dispersal, Genealogy and DNA in Relation to Sir Walter Raleigh’S Lost Colony of Roanoke

Where Have All the Indians Gone? Native American Eastern Seaboard Dispersal, Genealogy and DNA in Relation to Sir Walter Raleigh’s Lost Colony of Roanoke. Roberta Estes Copyright 2009, all rights reserved, submitted for publication [email protected] or [email protected] Abstract Within genealogy circles, family stories of Native American1 heritage exist in many families whose American ancestry is rooted in Colonial America and traverses Appalachia. The task of finding these ancestors either genealogically or using genetic genealogy is challenging. With the advent of DNA testing, surname and other special interest projects2, tools now exist to facilitate grouping participants in a way that allows one to view populations in historical fashions. This paper references and uses data from several of these public projects, but particularly the Melungeon, Lumbee, Waccamaw, North Carolina Roots and Lost Colony projects3. The Lumbee have long claimed descent from the Lost Colony via their oral history4. The Lumbee DNA Project shows significantly less Native American ancestry than would be expected with 96% European or African Y chromosomal DNA. The Melungeons, long held to be mixed European, African and Native show only one ancestral family with Native DNA5. Clearly more testing would be advantageous in all of these projects. This phenomenon is not limited to these groups, and has been reported by other researchers such as Bolnick (et al, 2006) where she reports finding in 16 Native American populations with northeast or southeast roots that 47% of the families who believe themselves to be full blooded or no less than 75% Native with no paternal European admixture find themselves carrying European or African y-line DNA. -

The Planting of English America ᇻᇾᇻ 1500–1733

2 The Planting of English America ᇻᇾᇻ 1500–1733 . For I shall yet to see it [Virginia] an Inglishe nation. SIR WALTER RALEIGH, 1602 s the seventeenth century dawned, scarcely a three European powers planted three primitive out- Ahundred years after Columbus’s momentous posts in three distant corners of the continent landfall, the face of m uch of the New World had within three years of one another: the Spanish at already been profoundly transformed. European Santa Fe in 1610, the French at Quebec in 1608, and, crops and livestock had begun to alter the very land- most consequentially for the future United States, scape, touching off an ecological revolution that the English at Jamestown, Virginia, in 1607. would reverberate for centuries to come. From Tierra del Fuego in the south to Hudson Bay in the north, disease and armed conquest had cruelly win- England’s Imperial Stirrings nowed and disrupted the native peoples. Several hundred thousand enslaved Africans toiled on Caribbean and Brazilian sugar plantations. From Feeble indeed were England’s efforts in the 1500s to Florida and New Mexico southward, most of the New compete with the sprawling Spanish Empire. As World lay firmly within the grip of imperial Spain. Spain’s ally in the first half of the century, England Bu t North America in 1600 remained largely took little interest in establishing its own overseas unexplored and effectively unclaimed by Euro- colonies. Religious conflict, moreover, disrupted peans. Then, as if to herald the coming century of England in midcentury, after King Henry VIII broke colonization and conflict in the northern continent, with the Roman Catholic Church in the 1530s, 25 26 CHAPTER 2The Planting of English America, 1500–1733 launching the English Protestant Reformation. -

Commonlit | Settling a New World: the Lost Colony of Roanoke Island

Name: Class: Settling a New World: The Lost Colony of Roanoke Island By National Park Service 2016 The Fort Raleigh National Historic Site is dedicated to the preservation of England’s first New World settlements, as well as the cultural legacy of Native Americans, European Americans, and African Americans who lived on Roanoke Island. In 1585 and 1587, England tried its hand at establishing a colonial presence in North America under the leadership of Sir Walter Raleigh. The attempts were failures on both accounts but they would come to form one of the most puzzling mysteries in early American history: the disappearance of the Roanoke colony. As you read, take notes on what circumstances or mistakes might have put the English settlers at a disadvantage in creating a lasting colony. [1] "About the place many of my things spoiled and broken, and my books torn from the covers, the frames of some of my pictures and maps rotted and spoiled with rain, and my armor almost eaten through with rust." - John White1 on the lost colony of Roanoke Island 1584 Voyage In the late sixteenth-century, England’s primary goal in North America was to disrupt Spanish "John White discovers the word "CROATOAN" carved at Roanoke's shipping. Catholic Spain, under the rule of Philip fort palisade" by Unknown is in the public domain. II,2 had dominated the coast of Central and South America, the Caribbean, and Florida for the latter part of the 1500s. Protestant England, under the rule of Elizabeth I,3 sought to circumvent4 Spanish dominance in the region by establishing colonies in the New World. -

We've Wondered, Sponsored Two Previous Expeditions to Roanoke Speculated and Fantasized About the Fate of Sir Island

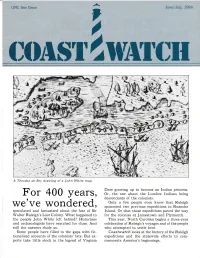

/'\ UNC Sea Grant June/July, 7984 ) ,, {l{HsT4IIHI'OII A Theodor de Bry dtawin! of a John White map Dare growing up to become an Indian princess. For 400 yearS, Or, the one about the Lumbee Indians being descendants of the colonists. Only a few people even know that Raleigh we've wondered, sponsored two previous expeditions to Roanoke speculated and fantasized about the fate of Sir Island. Or that those expeditions paved the way Walter Raleigh's Lost Colony. What happened to for the colonies at Jamestown and Plymouth. the people John White left behind? Historians This year, North Carolina begins a three-year and archaeologists have searched for clues. And celebration of Raleigh's voyages and of the people still the answers elude us. who attempted to settle here. Some people have filled in the gaps with fic- Coastwatc.tr looks at the history of the Raleigh tionalized.accounts of the colonists' fate. But ex- expeditions and the statewide efforts to com- perts take little stock in the legend of Virginia memorate America's beginnings. In celebration of the beginning an July, the tiny town of Manteo will undergo a transfor- Board of Commissioners made a commitment to ready the I mation. In the middle of its already crowded tourist town for the anniversary celebration, says Mayor John season, it will play host for America's 400th Anniversary. Wilson. Then, the town's waterfront was in a state of dis- Town officials can't even estimate how many thousands of repair. By contrast, at the turn of the century more than people will crowd the narrow streets. -

Foundation Document Overview, Fort Raleigh National Historic Site

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE • U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Foundation Document Overview Fort Raleigh National Historic Site North Carolina Contact Information For more information about the Fort Raleigh National Historic Site, contact: [email protected] or (252) 473-2111 or write to: Superintendent, Fort Raleigh National Historic Site, 1401 National Park Drive, Manteo, NC 27954 Purpose Significance and Fundamental Resources and Values Significance statements express why Fort Raleigh National Historic Site resources and values are important enough to merit national park unit designation. Statements of significance describe why an area is important within a global, national, regional, and systemwide context. These statements are linked to the purpose of the park unit, and are supported by data, research, and consensus. Significance statements describe the distinctive nature of the park and inform management decisions, focusing efforts on preserving and protecting the most important resources and values of the park unit. • The park preserves the site on Roanoke Island where English explorers attempted to create England’s first colonial settlement in the New World in 1585–1587. • Fort Raleigh National Historic Site is the birthplace of Virginia Dare, the first English child born in the New World. FORT RALEIGH NATIONAL HISTORIC SITE • Fort Raleigh National Historic Site preserves archeological preserves and interprets the site of the evidence of the first English colonization efforts, and first English Colony in the New World, is supports research on the history and archeology of the the site of the theatrical production, historic site and the associated peoples and events to reveal The Lost Colony, and interprets the information on the Roanoke voyages and resolve the mystery historical events of the the history of the of the lost colony of 1587.