Ancient Korea-Japan Relations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Representations of Pleasure and Worship in Sankei Mandara Talia J

Mapping Sacred Spaces: Representations of Pleasure and Worship in Sankei mandara Talia J. Andrei Submitted in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Columbia University 2016 © 2016 Talia J.Andrei All rights reserved Abstract Mapping Sacred Spaces: Representations of Pleasure and Worship in Sankei Mandara Talia J. Andrei This dissertation examines the historical and artistic circumstances behind the emergence in late medieval Japan of a short-lived genre of painting referred to as sankei mandara (pilgrimage mandalas). The paintings are large-scale topographical depictions of sacred sites and served as promotional material for temples and shrines in need of financial support to encourage pilgrimage, offering travelers worldly and spiritual benefits while inspiring them to donate liberally. Itinerant monks and nuns used the mandara in recitation performances (etoki) to lead audiences on virtual pilgrimages, decoding the pictorial clues and touting the benefits of the site shown. Addressing themselves to the newly risen commoner class following the collapse of the aristocratic order, sankei mandara depict commoners in the role of patron and pilgrim, the first instance of them being portrayed this way, alongside warriors and aristocrats as they make their way to the sites, enjoying the local delights, and worship on the sacred grounds. Together with the novel subject material, a new artistic language was created— schematic, colorful and bold. We begin by locating sankei mandara’s artistic roots and influences and then proceed to investigate the individual mandara devoted to three sacred sites: Mt. Fuji, Kiyomizudera and Ise Shrine (a sacred mountain, temple and shrine, respectively). -

Supernatural Elements in No Drama Setsuico

SUPERNATURAL ELEMENTS IN NO DRAMA \ SETSUICO ITO ProQuest Number: 10731611 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10731611 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 4 8 1 0 6 - 1346 Supernatural Elements in No Drama Abstract One of the most neglected areas of research in the field of NS drama is its use of supernatural elements, in particular the calling up of the spirit or ghost of a dead person which is found in a large number (more than half) of the No plays at present performed* In these 'spirit plays', the summoning of the spirit is typically done by a travelling priest (the waki)* He meets a local person (the mae-shite) who tells him the story for which the place is famous and then reappears in the second half of the.play.as the main person in the story( the nochi-shite ), now long since dead. This thesis sets out to show something of the circumstances from which this unique form of drama v/as developed. -

Tom Gill Lecture No

Meiji Gakuin Course No. 3505 Minority and Marginal Groups of Contemporary Japan Tom Gill Lecture No. 4 Koreans 在日コリアン HISTORY 1. Ancient History • Korean kings thought to be buried at Nara; many archaeological finds show Korean influence on Japan. • Also Chinese influence via Korea – Confucianism, kanji etc. • Koreans in Japan today like to point out Japan’s cultural debt to Korea. Ancient Japanese burial mounds … 塚・古墳 … may conceal remains of Korean kings? … the Japanese government doesn’t want to know. Radical emperor? During a news conference to mark his 68th birthday, Emperor Akihito mentioned a historical document showing that one of his eighth- century ancestors was a descendant of immigrants from the Korean Peninsula. He said he felt a close "kinship" with Korea. 『続日本記』によると The Emperor, quoting from the "Shoku Nihongi" ("Chronicles of Japan"), compiled in 797, said the mother of Emperor Kanmu (737- 806) had come from the royal family of Paekche, an ancient kingdom of Korea. 桓武天皇の母親はコリアの皇室出身者 It was the first time a member of the Imperial family had ever publicly noted the family's blood ties with 23 Korea. December 2002 韓国で大歓迎 His remark received a warm welcome in Seoul. South Korean President Kim Dae Jung praised the Emperor for his "correct understanding of history." 手を上げてください I wonder how many of the Meigaku students here today know that Emperor Akihito himself has stated that he is of Korean descent? 明学の学生たち、明仁天皇自身が朝鮮の ルーツを認めているて、知っています か? 朝日だけ報道した Of the five national papers, the Mainichi, the Yomiuri, the Sankei and the Nihon Keizai Shinbun ignored the Emperor's Korea reference. -

The Myth of the Goddess of the Undersea World and the Tale of Empress Jingu’S Subjugation of Silla

Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 1993 20/2-3 The Myth of the Goddess of the Undersea World and the Tale of Empress Jingu’s Subjugation of Silla Akima Toshio In prewar Japan, the mythical tale of Empress Jingii’s 神功皇后 conquest of the Korean kingdoms comprised an important part of elementary school history education, and was utilized to justify Japan5s coloniza tion of Korea. After the war the same story came to be interpreted by some Japanese historians—most prominently Egami Namio— as proof or the exact opposite, namely, as evidence of a conquest of Japan by a people of nomadic origin who came from Korea. This theory, known as the horse-rider theory, has found more than a few enthusiastic sup porters amone Korean historians and the Japanese reading public, as well as some Western scholars. There are also several Japanese spe cialists in Japanese history and Japan-Korea relations who have been influenced by the theory, although most have not accepted the idea (Egami himself started as a specialist in the history of northeast Asia).1 * The first draft of this essay was written during my fellowship with the International Research Center for Japanese Studies, and was read in a seminar organized by the institu tion on 31 January 199丄. 1 am indebted to all researchers at the center who participated in the seminar for their many valuable suggestions. I would also like to express my gratitude to Umehara Takeshi, the director general of the center, and Nakanism Susumu, also of the center, who made my research there possible. -

Chinese Culture Themes and Cultural Development: from a Family Pedagogy to A

Chinese Culture themes and Cultural Development: from a Family Pedagogy to a Performance-based Pedagogy of a Foreign Language and Culture DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Nan Meng Graduate Program in East Asian Languages and Literatures The Ohio State University 2012 Dissertation Committee: Galal Walker, Advisor Mari Noda Mineharu Nakayama Copyright by Nan Meng 2012 Abstract As the number of Americans studying and working in China increases, it becomes important for language educators to reconsider the role of culture in teaching Chinese as a foreign language. Many American learners of Chinese fail to achieve their communicative goals in China because they are unable to establish and convey their intentions, or to interpret their interlocutors’ intentions. Only knowing the linguistic code is not sufficient; therefore, it is essential to develop learners’ abilities to be socialized to Chinese culture. A working definition of culture theme as a series of situated acts associated with cultural values is proposed. In order to explore how children acquire culture themes with competent social guides, a quantitative comparative study of maternal speech and a micro-ethnographic discourse analysis of adult-child interactions are presented. Parental discourse patterns are shown to be culturally specific activities that not only foster language development, but also maintain normative dimensions of social life. The culture themes are developed at a young age through children’s interactions with Chinese speakers under the guidance of their parents or caregivers. In order to communicate successfully people have to do things within the shared time and space provided by the culture. -

JAPANESE HISTORY Paul Clark, Ph.D

HUMANITIES INSTITUTE JAPANESE HISTORY Paul Clark, Ph.D Course Description: This course offers an introduction to the history of Japan from pre-history to the present. We will trace the history of Japan in several different epochs. First, we will investigate how Japanese civilization emerged and how early governments were constituted. Second, we will consider the Yamato Clan and the Nara and Heian periods. Third, we will study the rise of the period dominated by warriors, the first shōgunate and the feudal era. Fourth, we will consider how and why the bakufu (tent government--shōgunate) lost its vitality in the late 18th century and why it was unable to deal with the international crisis which led to its demise. We will discuss the irony of how a military coup d’état, initiated by samurai, led to the dissolution of a samurai-based society and to the construction of the modern Japanese state. Along the way we will study how democracy in the Meiji, Taishō and Shōwa eras failed and led to the militarism of the Pacific War. Fifth, we will discern whether or not the American occupation of Japan led to substantive changes within Japanese culture, economics and government. Finally, we will discuss Japan today. In particular, we will examine modern Japanese society, the government and the enduring problem of the economic recession. About the Professor The course was prepared by Paul Clark, Ph.D. who is an East Asia area specialist and Associate Professor of History at West Texas A&M University. Dr. Clark is the author of The Kokugo Revolution: Education, Identity and Language Policy in Imperial Japan (2009) and is the recipient of a 2006 Fulbright-Hays Faculty Research Abroad Fellowship. -

Of Mice and Maidens: Ideologies of Interspecies Romance in Late Medieval and Early Modern Japan

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2014 Of Mice and Maidens: Ideologies of Interspecies Romance in Late Medieval and Early Modern Japan Laura Nuffer University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Asian Studies Commons, and the Medieval Studies Commons Recommended Citation Nuffer, Laura, "Of Mice and Maidens: Ideologies of Interspecies Romance in Late Medieval and Early Modern Japan" (2014). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 1389. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/1389 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/1389 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Of Mice and Maidens: Ideologies of Interspecies Romance in Late Medieval and Early Modern Japan Abstract Interspecies marriage (irui kon'in) has long been a central theme in Japanese literature and folklore. Frequently dismissed as fairytales, stories of interspecies marriage illuminate contemporaneous conceptions of the animal-human boundary and the anxieties surrounding it. This dissertation contributes to the emerging field of animal studies yb examining otogizoshi (Muromachi/early Edo illustrated narrative fiction) concerning elationshipsr between human women and male mice. The earliest of these is Nezumi no soshi ("The Tale of the Mouse"), a fifteenth century ko-e ("small scroll") attributed to court painter Tosa Mitsunobu. Nezumi no soshi was followed roughly a century later by a group of tales collectively named after their protagonist, the mouse Gon no Kami. Unlike Nezumi no soshi, which focuses on the grief of the woman who has unwittingly married a mouse, the Gon no Kami tales contain pronounced comic elements and devote attention to the mouse-groom's perspective. -

The Goddesses' Shrine Family: the Munakata Through The

THE GODDESSES' SHRINE FAMILY: THE MUNAKATA THROUGH THE KAMAKURA ERA by BRENDAN ARKELL MORLEY A THESIS Presented to the Interdisciplinary Studies Program: Asian Studies and the Graduate School ofthe University ofOregon in partial fulfillment ofthe requirements for the degree of Master ofArts June 2009 11 "The Goddesses' Shrine Family: The Munakata through the Kamakura Era," a thesis prepared by Brendan Morley in partial fulfillment ofthe requirements for the Master of Arts degree in the Interdisciplinary Studies Program: Asian Studies. This thesis has been approved and accepted by: e, Chair ofthe Examining Committee ~_ ..., ,;J,.." \\ e,. (.) I Date Committee in Charge: Andrew Edmund Goble, Chair Ina Asim Jason P. Webb Accepted by: Dean ofthe Graduate School III © 2009 Brendan Arkell Morley IV An Abstract ofthe Thesis of Brendan A. Morley for the degree of Master ofArts in the Interdisciplinary Studies Program: Asian Studies to be taken June 2009 Title: THE GODDESSES' SHRINE FAMILY: THE MUNAKATA THROUGH THE KAMAKURA ERA This thesis presents an historical study ofthe Kyushu shrine family known as the Munakata, beginning in the fourth century and ending with the onset ofJapan's medieval age in the fourteenth century. The tutelary deities ofthe Munakata Shrine are held to be the progeny ofthe Sun Goddess, the most powerful deity in the Shinto pantheon; this fact speaks to the long-standing historical relationship the Munakata enjoyed with Japan's ruling elites. Traditional tropes ofJapanese history have generally cast Kyushu as the periphery ofJapanese civilization, but in light ofrecent scholarship, this view has become untenable. Drawing upon extensive primary source material, this thesis will provide a detailed narrative ofMunakata family history while also building upon current trends in Japanese historiography that locate Kyushu within a broader East Asian cultural matrix and reveal it to be a central locus of cultural production on the Japanese archipelago. -

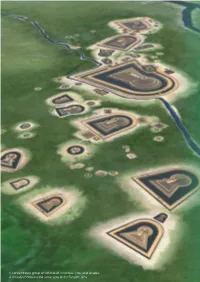

A Concentrated Group of Kofun Built in Various Sizes and Shapes a Virtually Reconstructed Aerial View of the Furuichi Area Chapter 3

A concentrated group of kofun built in various sizes and shapes A virtually reconstructed aerial view of the Furuichi area Chapter 3 Justification for Inscription 3.1.a Brief Synthesis 3.1.b Criteria under Which Inscription is Proposed 3.1.c Statement of Integrity 3.1.d Statement of Authenticity 3.1.e Protection and Management Requirements 3.2 Comparative Analysis 3.3 Proposed Statement of Outstanding Universal Value 3.1.a Brief Synthesis 3.Justification for Inscription 3.1.a Brief Synthesis The property “Mozu-Furuichi Kofun Group” is a tomb group of the king’s clan and the clan’s affiliates that ruled the ancient Japanese archipelago and took charge of diplomacy with contemporary East Asian powers. The tombs were constructed between the late 4th century and the late 5th century, which was the peak of the Kofun period, characterized by construction of distinctive mounded tombs called kofun. A set of 49 kofun in 45 component parts is located on a plateau overlooking the bay which was the maritime gateway to the continent, in the southern part of the Osaka Plain which was one of the important political cultural centers. The property includes many tombs with plans in the shape of a keyhole, a feature unique in the world, on an extraordinary scale of civil engineering work in terms of world-wide constructions; among these tombs several measure as much as 500 meters in mound length. They form a group, along with smaller tombs that are differentiated by their various sizes and shapes. In contrast to the type of burial mound commonly found in many parts of the world, which is an earth or piled- stone mound forming a simple covering over a coffin or a burial chamber, kofun are architectural achievements with geometrically elaborate designs created as a stage for funerary rituals, decorated with haniwa clay figures. -

Basic Study on Oharidadera and Taikoji Temples

Bulletin of the National Museum of Japanese History Vol. 179 November 2013 Basic Study on Oharidadera and Taikoji Temples YOSHIKAWA Shinji The abandoned temple of Okuyama (Okuyama Kumedera Temple) located at Okuyama in Asuka Village, Nara Prefecture is considered to be an old temple founded in the 620s or 630s, and identified with the Oharidadera Temple found in bibliographical sources of olden times. However, with regard to the circumstances of the foundation of the Oharidadera Temple, to date, no firmly established theory has been formed. In this paper by rereading historical materials relating to ancient times through to the medieval period, the following conclusions were obtained. 1. Oharidadera Temple in Asuka was the leading convent in the late 7th century, and even in the 8th century the temple had a close relation with the Imperial Family. It was confirmed that concurrently with the relocation of the capital to Heijyo-kyo, the temple was moved to the northern outskirts of Heijyo-kyo, and the new temple was also called Oharidadera. 2. The Taikoji Temple in Nara, mentioned in historical materials covering the Heian period and later, in view of its geographical position, can be assumed to be the same as the Heijyo Oharidadera Temple. It would be reasonable to consider that Oharidadera Temple had the Buddhist name, Taikoji, since before the relocation of the capital to Heijyo-kyo. 3. Private estates owned by Taikoji Temple in Yamato Province, mentioned in the Kanyo Ruijusho collection, were systematically arranged in locations convenient for overland transportation on the Nakatsu-Michi road and water transport on the Yamato River; against this background a strong admin- istrative and financial power can be inferred. -

Origins and Characteristics of the Japanese Collection in the British Library

ORIGINS AND CHARACTERISTICS OF THE JAPANESE COLLECTION IN THE BRITISH LIBRARY YU-YING BROWN THE British Library's antiquarian Japanese collection has long been regarded as one of the finest outside Japan.^ Its quality and quantity are such that the descriptive catalogue^ compiled by my predecessor, the late Kenneth Gardner,^ had to be limited to pre-1700 printed books. Even then, it included 637 items of outstanding rarity.^ These range from the Hyakumanto daratii ^-^m^tmf^ (Empress Shotoku's 'One Million Pagoda Charms') of AD 764-70; to books printed in medieval Buddhist monasteries (imprints known as Kastiga-ban ^B^^ Jodokyo-ban &±^f&yKdya-ban ,^if-lfe, etc., from the names of their associated temples or sects); Chinese classical works printed in Japan (especially Gozan- ban ELUtife ); and the early movable-type editions (Kokatsuji-ban ^ffi^^tK), which include Saga-bon ^m'^ and those rarest of all Japanese books, volumes printed by the Jesuit Mission Press, the Kirishitan-ban ^ u •>? >W.. In the category of Kokatsuji-ban., the best yardstick with which to measure the comparative strength of fine antiquarian collections, the British Library has about 120, a holding comparable with those of such great Japanese libraries as Tenri Central Library in Nara, Daitokyu Memorial Library and the Toyo Bunko (Oriental Library) in Tokyo. The early date and rarity of much of the Japanese collection in the British Library owes a good deal to the acquisitions made by the British Museum, through purchase and gift, from four inspired collectors. They were Engelbert Kaempfer (1651-1716),^ a German physician and traveller who worked at Deshima, the Dutch East India Company's trading post in Nagasaki; Phihpp Franz von Siebold (1796-1866), Kaempfer's compatriot and likewise a doctor at Deshima; Sir Ernest Satow (1843-1929), a distinguished British diplomat and bibliophile; and William Anderson (1842-1900), a Scottish surgeon. -

Japan Looking at the World Looking at Japan : European Expansion Into

Japan Looking at the World Looking at Japan European Expansion into East Asia, the Formation of the Japanese Concept and Perception of Colonial Rule as well as European Responses c. 19001 Harald Kleinschmidt, Tokyo An Interactionist Approach to the History of International Relations On 8 February 1868, the newly installed Meiji Government of Japan issued its proclamation nr 5. In this proclamation, it declared that it would honor the treaties that had been concluded between Japan and states in Europe and North America since 1854, but that it would also seek their revision in ac- cordance with ‘universal public law’ 宇内の公法 (udai no kōhō). On behalf of the government, Higashikuze Michitomi 東久世通禧, then in office as Director General Agency for Foreign Affairs 外国事務総督 (Gaikoku Jimu Sōtoku), communicated the contents of the proclamation to foreign diplo- matic envoys then accredited in Japan.2 The proclamation thus articulated the perception that there was a hierarchy of two legal frameworks that could be addressed for different, if not mutually exclusive purposes. Within this 1 Paper read to the Historical Institute of the University of Greifswald, 24 April 2017. 2 GENERAL AGENCY FOR FOREIGN AFFAIRS 外国事務総督 (Gaikoku Jimu Sōtoku): “Gaikō ni kan suru Fukokusho 外交に関スル布告書” (Government Proclamation Relating to Diplomacy [dated 8 February 1868 = 15th day of the first month of year Keio 4, concerning the treaties between Japan and other states, written by ŌKUBO Toshimichi 大 久保利道 and MUTSU Munemitsu 陸奥宗光]), Dai Nihon gaikō monjo 大日本外交文書 (Diplomatic Records of Japan), nr 97, vol. 1, Nihon Kokusai Kyōkai 日本国際協会 1938: 227–28. HIGASHIKUZE Michitomi: Nikki 日記 (Diary), vol.