Analysis of Anti-Languages in Chinese Raps

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thomé H. Fang, Tang Junyi and the Appropriation of Huayan Thought

Thomé H. Fang, Tang Junyi and the Appropriation of Huayan Thought A thesis submitted to the University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities 2014 King Pong Chiu School of Arts, Languages and Cultures TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents 2 List of Figures and Tables 4 List of Abbreviations 5 Abstract 7 Declaration and Copyright Statement 8 A Note on Transliteration 9 Acknowledgements 10 Chapter 1 - Research Questions, Methodology and Literature Review 11 1.1 Research Questions 11 1.2 Methodology 15 1.3 Literature Review 23 1.3.1 Historical Context 23 1.3.2 Thomé H. Fang and Huayan Thought 29 1.3.3 Tang Junyi and Huayan Thought 31 Chapter 2 – The Historical Context of Modern Confucian Thinkers’ Appropriations of Buddhist Ideas 33 2.1 ‘Ti ’ and ‘Yong ’ as a Theoretical Framework 33 2.2 Western Challenge and Chinese Response - An Overview 35 2.2.1 Declining Status of Confucianism since the Mid-Nineteenth Century 38 2.2.2 ‘Scientism’ as a Western Challenge in Early Twentieth Century China 44 2.2.3 Searching New Sources for Cultural Transformation as Chinese Response 49 2.3 Confucian Thinkers’ Appropriations of Buddhist Thought - An Overview 53 2.4 Classical Huayan Thought and its Modern Development 62 2.4.1 Brief History of the Huayan School in the Tang Dynasty 62 2.4.2 Foundation of Huayan Thought 65 2.4.3 Key Concepts of Huayan Thought 70 2.4.4 Modern Development of the Huayan School 82 2.5 Fang and Tang as Models of ‘Chinese Hermeneutics’- Preliminary Discussion 83 Chapter 3 - Thomé H. -

Paper Title (Use Style: Paper Title)

International Academic Workshop on Social Science (IAW-SC 2013) Grotesque and Gaudy World of Music, Indispensable Narrative Pen Study on The Narrative Strategy of Modern Chinese Pop Songs’ Lyrics Chunjing Zhang College of Applied Technology Southwest University Chongqing,China [email protected] Abstract—Since the 1990s, the creation of pop songs’ lyrics has symbol presents "conation ", which promotes recipient to undergone a lot of changes, transforming from the past take action. According to Jacobsen’s brilliant analysis, lyrics emphasis on inner expression to frequent use of narration. appear to be more emotional or strongly conative. Therefore, Thus, the grotesque and gaudy world of music, concentrating the lyrics have a strong tendency of appealing. Answering is on creators ’narrative pen, unfolds vividly. Some important the basic trend of the lyrics, narrative strategy of “I tell you" narrative strategy has gradually taken shape, including basic is the most fundamental sending mode of lyrics. The narrative strategy of “I tell you” and public participation in appearance of subject expressing is an important “telling a story”, Demonstration of details and fragments in life characteristics of the lyrics. of whole narration and defamiliarization on narration. There are too many examples that we cannot cite them all. Keywords-lyrics; pop songs; narration According to the study of the highest search volume of 100 new songs lyrics on Baidu MP3 search, the author find that 95% of the lyrics comprise the basic strategy of "I tell you", I. INTRODUCTION including "I", "you" or slightly distorted "I" and "you", even No matter what kinds of art form, story-telling is the if starting in the fashion of third person and through the most attractive method. -

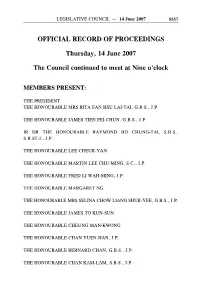

OFFICIAL RECORD of PROCEEDINGS Thursday, 14 June

LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 14 June 2007 8865 OFFICIAL RECORD OF PROCEEDINGS Thursday, 14 June 2007 The Council continued to meet at Nine o'clock MEMBERS PRESENT: THE PRESIDENT THE HONOURABLE MRS RITA FAN HSU LAI-TAI, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE JAMES TIEN PEI-CHUN, G.B.S., J.P. IR DR THE HONOURABLE RAYMOND HO CHUNG-TAI, S.B.S., S.B.ST.J., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LEE CHEUK-YAN THE HONOURABLE MARTIN LEE CHU-MING, S.C., J.P. THE HONOURABLE FRED LI WAH-MING, J.P. THE HONOURABLE MARGARET NG THE HONOURABLE MRS SELINA CHOW LIANG SHUK-YEE, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE JAMES TO KUN-SUN THE HONOURABLE CHEUNG MAN-KWONG THE HONOURABLE CHAN YUEN-HAN, J.P. THE HONOURABLE BERNARD CHAN, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE CHAN KAM-LAM, S.B.S., J.P. 8866 LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 14 June 2007 THE HONOURABLE MRS SOPHIE LEUNG LAU YAU-FUN, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LEUNG YIU-CHUNG THE HONOURABLE SIN CHUNG-KAI, J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE PHILIP WONG YU-HONG, G.B.S. THE HONOURABLE WONG YUNG-KAN, J.P. THE HONOURABLE JASPER TSANG YOK-SING, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE HOWARD YOUNG, S.B.S., J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE YEUNG SUM THE HONOURABLE LAU CHIN-SHEK, J.P. THE HONOURABLE LAU KONG-WAH, J.P. THE HONOURABLE LAU WONG-FAT, G.B.M., G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MIRIAM LAU KIN-YEE, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE EMILY LAU WAI-HING, J.P. -

Sex, Gender, and Desire §1 Fantasy 就像你註定是要離開的 Like You Were Destined to Leave

The performance of identity in Chinese popular music Groenewegen, J.W.P. Citation Groenewegen, J. W. P. (2011, June 15). The performance of identity in Chinese popular music. Retrieved from https://hdl.handle.net/1887/17706 Version: Not Applicable (or Unknown) Licence agreement concerning inclusion of doctoral thesis in the License: Institutional Repository of the University of Leiden Downloaded from: https://hdl.handle.net/1887/17706 Note: To cite this publication please use the final published version (if applicable). Chapter 3: Sex, Gender, and Desire §1 Fantasy 就像你註定是要離開的 Like you were destined to leave. [No guitar, silence. Xiao He seems to say to himself:] 對不起 Sorry. [To the audience:] 世界卻不會 The world, however, won’t 因為你走了而停止 stop turning because you’re gone. In the verses of SIMPLE TRUTH 簡單的道理 that precede the above, Xiao He sings of impossible love. Xiao He’s desire for his Lady is inflamed by her inaccessibility. In these last lines, Xiao He traverses the fanta- sy: he reveals his Lady to be insubstantial and redundant. Nevertheless, the ensuing instrumental, tango-like chorus creates a mixed feeling of sadness and relief. It does not suggest the awakening to propriety, to commonsensical reality that might be ex- pected. On the contrary, SIMPLE TRUTH ridicules common sense from the start. It starts with a joke: [Background noises of people talking, drinking, laughing, a few seemingly ran- domly placed staccato chords on an acous- Illustration 3.1: Xiao He and Li Tieqiao tic guitar, pause. Xiao He starts sing-talk- performing SIMPLE TRUTH with Glorious ing a capella:] Pharmacy at the Midi Modern Music Festival 2004. -

Sodagreen Does It Again

SUNDAY, JULY 6 , 2 0 0 8 PAGE 1 3 — The 19th Golden Melody Awards nominees and winners — Pop Music category (演唱類) ◆ Best Song ◆ Best Mandarin Male Singer 最佳年度歌曲 最佳國語男歌手獎 * Incomparable Beauty (無與倫比的美麗) in * ������������Eason Chan (陳奕迅) for Admit It (認了吧) Incomparable Beauty (無與倫比的美麗) by * ��������Tank for Keep Fighting (延長比賽) Sodagreen (蘇打綠) * ������Shin (信) for I Am I (我就是我) * Darwin (達爾文) in Goodbye & Hello by Tanya * Y������������ang Pei-an (楊培安) for Pei-an Yang’s Album Chua (蔡健雅) No. 2 (楊培安II) * Blue and White Porcelain (青花瓷) in On the * G����������ary Tsao (曹格) for Super Sunshine Run (我很忙) by Jay Chou (周杰倫) * �������������Khalil Fong (方大同) for Wonderland (未來) * Love Song in Wonderland (未來) Khalil Fong (方大同) ◆ Best Taiwanese Male Singer * Against the Light (逆光) in Against the Light 最佳台語男歌手獎 (逆光) by Stefanie Sun (孫燕姿) * Shih W��������en-bin (施文彬) for Be Together * Blink of an Eye (一眼瞬間) in Star by A-mei Tonight (今夜我陪你) (張惠妹) * W��������ang Shi-x�����ian (王識賢) for Man of Iron (堅強) P13 * Hsiao Huang-chi (蕭煌奇) for Love Songs ◆ Best Mandarin Album 真情歌 P13 ( ) 最佳國語專輯獎 * Incomparable Beauty (無與倫比的美麗) by ◆ Best Mandarin Female Singer Features Sodagreen (蘇打綠) 最佳國語女歌手獎 * Star by A-mei (張惠妹) 張惠妹 Features * �������A-mei ( ) for Star * Against the Light (逆光) by Stefanie Sun (孫燕 * ��������������Stefanie Sun (孫燕姿) for Against the Light 姿) (逆光) * Goodbye & Hello by Tanya Chua (蔡健雅) * ������������Fish Leong (梁靜茹) for J’Adore (崇拜) Live Is … (拉活) by Karen Mok (莫文蔚) * ������������Tanya Chua (蔡健雅) for Goodbye & Hello Sodagreen does it again * On the Run (我很忙) by Jay Chou (周杰倫) * �����������Karen Mok (莫文蔚) for Live Is … (拉活) * ����������Joi Tsai (蔡淳佳) for Joi Blessed (慶幸擁有) Despite a slew of nominations and gongs, Jay Chou shunned this year’s Golden Melody Awards ◆ Best Taiwanese-language Album 最佳台語專輯獎 ◆ Best Taiwanese Female Singer BY HO YI 人間有愛 最佳台語女歌手獎 STAFF REPORTER * Love of Life III – Companionship ( 3—歡喜作伴) from TV sound track * ������������Chen Si-an (陳思安) for Appreciation (體會) 真情歌 蕭 an evening that saw the took place at Taipei Arena (台北巨 ceremony. -

Contemporary Chinese Performance Culture 当代中国表演艺术文化

Course Syllabus © Emily Wilcox - Fall 2019 University of Michigan ASIAN 356 / RCHUMS 374 - 001 Contemporary Chinese Performance Culture 当代中国表演艺术文化 Course Time and Location: MW 5:30-6:50 PM, 1405 MLB Instructor: Dr. Emily Wilcox Office Location: South Thayer 5159 (5th Floor) Office Hours: Tuesdays, 2:00-4:00 PM and by appointment Email: [email protected] Course Description This course examines twenty-first century Chinese culture through the lens of performance. Starting with the 2008 Beijing Olympic Opening Ceremonies, the course uses significant works as case studies to examine a range of genres in 21st-century Chinese performance culture: global mass mediated performance, avant-garde theater, dance, tourism productions, popular music , and intercultural Chinese opera. Students will learn to examine these works as cultural texts embedded in local, national, and global histories. They will become fluent in the landscape of performance culture in China, including major artists, organizations, and ideas. In addition, students will become familiar with important thematic and theoretical approaches in Chinese performance and media studies. Prerequisites NONE. No prior knowledge of Chinese language, Chinese culture, or the practice and analysis of performance is required to enroll in this class. All required readings and discussions will be held in English, and students will be introduced to performance terminology and methods at a beginner level. Course Syllabus © Emily Wilcox - Fall 2019 University of Michigan Learning Objectives This course meets the expectations for culture content courses in Asian Studies and for the general Humanities requirement. Thus, it is designed both for students with a particular interest in Asian language and culture and for students with little prior knowledge of Asian studies who are taking the course to expand their general broad knowledge of the arts and humanities. -

China Wind Promoting One China and the Study One (Global) Chinese Culture

10 China wind Promoting One China and The Study one (global) Chinese culture ‘Sonic Traveler’ is a jazz fusion band from Hong Kong China’s that combines Western and Chinese instruments. the piano concerto and combines this with Chinese idioms in its instrumentation, country music: melodies and other musical aspects. The Cultural Revolution (1966-76) saw the large scale destruction of cultural artefacts and a restrictive government that firmly controlled the public cultural domain. Popular China wind music was forbidden and all music had to serve an (ideological) purpose in forwarding the revolution. Around forty years later, however, it seems that China is learning to appreciate Milan Ismangil Chinese Pop music in greater China (Taiwan, HK and its historical heritage and uses it to wield China) saw a turn towards the traditional in the early soft power both domestically and abroad. State propagated programs that promote 2000s with the arrival of a new genre called China wind. the Chinese language and culture, such as This genre, created and popularized by Taiwan based the Confucius Institutes, or the One Belt One Road program, showcase a China that artists quickly grew in popularity and since its inception has is more than willing to promote its culture seen many artists emulate a similar style. China wind as a to the outside world. This (re)appreciation of Chinese idioms genre has a high political potential due to its depiction of can also be tied to an increasing nationalist Chineseness, which makes it an easy choice for promoting discourse propagated by the communist party in China. -

Slashing Three Kingdoms: a Case Study in Fan Production on the Chinese Web†

Slashing Three Kingdoms: A Case Study in Fan Production on the Chinese Web† Xiaofei Tian “A damned mob of scribbling women. .” —Nathaniel Hawthorne (1855) † I am grateful to the two anonymous The Three Kingdoms period, popularly taken as lasting from the chaotic MCLC readers for their feedback and to last years of the Han to the unification of China in 280 CE, has been a Kirk Denton for his many corrections and comments. lasting inspiration for the Chinese literary imagination.1 For more than a millennium, numerous works, from written to visual, have been produced 1 Properly speaking, the Three Kingdoms did not begin until the last Han emperor about the Three Kingdoms, and the interest in the period is only growing was formally deposed in 220CE, but stronger today. Romance of the Three Kingdoms (Sanguo yanyi), a master- for most Chinese readers the focus of interest regarding “Three Kingdoms” piece of the Chinese novel produced in the fourteenth century, has been was in the last decades of what was, widely disseminated and reworked in China, Japan, Korea, and Vietnam, technically, still the Han dynasty. making the fascination with the Three Kingdoms not just a Chinese but also an East Asian phenomenon. A new chapter in this long tradition of the construction of the Three Kingdoms imaginary has opened at the turn of the twenty-first century by a body of works produced by young Chinese female fans in cyberspace. This essay focuses on a particular subset of these fan works, namely, male-homoerotic fiction and music videos (MVs). In studying this particular subset of Three Kingdoms fan production on the ÓÓ{ÊUÊSlashing Three Kingdoms Internet, I attempt to provide a new perspective on the representation of the Three Kingdoms in contemporary Chinese society as well as raise some issues with a broader significance for Chinese fan production. -

Jay Chou's Zhongguo Feng: Songs and Identity

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Malaya Students Repository JAY CHOU'S ZHONGGUO FENG: SONGS AND IDENTITY SU ZEKAI CULTURE CENTRE UNIVERSITY OF MALAYA KUALA LUMPUR 2018 JAY CHOU'S ZHONGGUO FENG: SONGS AND IDENTITY SU ZEKAI DESSERTATION SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF PERFORMING ARTS (MUSIC) CULTURE CENTRE UNIVERSITY OF MALAYA KUALA LUMPUR 2018 UNIVERSITY OF MALAYA ORIGINAL LITERARY WORK DECLARATION Name of Candidate: SU ZEKAI (I.C/Passport No: G36371096 ) Registration/Matric No: RGI150018 Name of Degree: MASTER OF PERFORMING ARTS (MUSIC) Title of Project Paper/Research Report/Dissertation/Thesis (“this Work”): JAY CHOU'S ZHONGGUO FENG: SONGS AND IDENTITY Field of Study: Popular Music I do solemnly and sincerely declare that: (1) I am the sole author/writer of this Work; (2) This Work is original; (3) Any use of any work in which copyright exists was done by way of fair dealing and for permitted purposes and any excerpt or extract from, or reference to or reproduction of any copyright work has been disclosed expressly and sufficiently and the title of the Work and its authorship have been acknowledged in this Work; (4) I do not have any actual knowledge nor do I ought reasonably to know that the making of this work constitutes an infringement of any copyright work; (5) I hereby assign all and every rights in the copyright to this Work to the University of Malaya (“UM”), who henceforth shall be owner of the copyright in this Work and that any reproduction or use in any form or by any means whatsoever is prohibited without the written consent of UM having been first had and obtained; (6) I am fully aware that if in the course of making this Work I have infringed any copyright whether intentionally or otherwise, I may be subject to legal action or any other action as may be determined by UM. -

Combination of Malay Traditional and Chinese Popular Musical Elements Into a New Mandopop Composition

COMBINATION OF MALAY TRADITIONAL AND CHINESE POPULAR MUSICAL ELEMENTS INTO A NEW MANDOPOP COMPOSITION La i Kee Nee Bachelor of App U«.>d Arts witb Honours (Music) 2017 TRADITIONAL ,"WJvk'-,c~kJ E:,LILM[ENrTS n"T'n A LAIKEE Projek ini merupakan salah satu keperluan untuk ljazall Sarjana Muda Sent Gunaan dengan Kepujian (Muzik) Fakulti Seni Gunaan dan Kreatif UNIVERSITl :V1ALAYSIA SARAWAK 20]7 UNIVERSITI MALA YSIA SARA W AK Grade: Please tick (~ ) f inal Year Project Report 1/ 1 Masters D PhD D DECLARAnON OF ORIGINAL WORK This declaration is made on the . lbth day of , :r\l~ .. 20 17. • StutJel1t" s Declarat ion: I, LAl KEE NEE, 47235, FACULTY OF APPLIED AND CREATIVE ARTS hereby declare that the work entitled COMBIN ATION OF MALAY TRADITIONAL AND CHINESE PUPILAR MUSICAL ELEMENTS INTO A NEW MAN DOPOP COMPOS ITI ON is my original work. I have not copied from any other stud ents' work or fr om any other sources except where due reference or acknowledgement is made explicitly in th e tex t, nor has any part been written for me by another person. ~~~f\P' Date submnted • LAl KEE NEE (47235) Supervisor's Declaration: I, DR. HilA SOCK SIANG hereby cenifies th at the work entitled COMBINATION OF MALAY TRADITIONA L AND CHINESE PUPTLAR MUSICAL ELEM ENTS INTO A NEW MANDOPOP COMPOSITION was prepared by the above named student , and was subm itted to the "FACULTY" as a * paJ1i al/full fu lfillment for the conferment of BACHELOR OF APPLI ED ARTS WITH HONOURS (MUSIC), and the aforementioned work, to the best of my knowledge, is the sa id student's work. -

ASPAC 2017 Who Will Be Offering Their Insights Into This Important Region

Campus Map Reflecting (on) the Oregon State Capitol Ford Hall State Street Asia-Pacific: Places, Star Trees Rose Garden 20 33 3 North Lawn 19 21 Montag 31 Den 48 11 41 Street 13th 52 32 49 14 22 65 8 30 Relations, Systems Ferry Street 50 51 42 Ferry Street Church Street 4 Cottage Street 13 Quad 9 47 38 26 10 34 7 28 10 P r 18 17 37 in 15 44 g l 40 e P a r Permit k UC w Mill Race Parking Lot a 23 12th Street 12th Street 14th y Jackson Winter Street Plaza 24 5 54 36 16 43 Permit Brown Field Hatfield Willamette Parking Lot 27 Fountain Heritage Center Sky Bridge Mill Street Mill Street Permit Parking Lot 46 1 Sparks Field 45 53 Permit 39 35 12 2 Parking Lot 25 Visitor Parking Lot Tennis Courts Bellevue Street Softball Field Handicapped Access Oak Street Emergency Telephone Automated External Defibrillator Salem Hospital Parking Lot Short-term Parking Meters Leslie Street Updated: 7/22/16 Capitol Street University Street Mission Street Bush’s Pasture Park 29 1 Admission Office (undergraduate) 21 Gatke Hall 41 Smullin Hall 2 Alpha Chi Omega Sorority 22 Global Learning Center (including 42 Southwood Hall 3 Art Building International Education) 43 Lestle J. Sparks Center (including Equity & Empowerment Center) 23 Goudy Commons 44 Terra House 4 Atkinson Annex 24 Mark O. Hatfield Library 45 Tokyo International 5 Atkinson Graduate School of Management 25 Kaneko Commons University of America (Seeley G. Mudd Building) 26 Lausanne Hall 46 University Apartments 6 Baxter Hall 27 Lee House 47 University Services Building 7 Belknap Hall 28 Matthews Hall 48 University Services Annex 8 Bishop Wellness Center (Student Health) 29 McCulloch Stadium and Athletics Complex 49 Waller Hall 9 Cascadia House 30 Montag Center 50 Walton Hall 10 College of Law 31 Northwood Hall 51 Westwood Hall (Truman Wesley Collins Legal Center) 32 Olin Science Center 52 Willamette Academy 11 Collins Science Center 33 Oregon Civic Justice Center 53 Willamette International Studies House 12 Delta Gamma Sorority (WISH) 34 M. -

Meeting Boosts Chinaarab Ties Amid Contagion

Lifestyle Premium US to force out Fatal crash foreign students At least 21 die after crowded bus Fashion, accessories, books, learning online plunges into Guizhou reservoir cocktails, food, and more... LP1-4 WORLD, PAGE 19 CHINA, PAGE 5 Lifestyle Premium Fashion, acc, grooming, beverages, CHINADAILY recipes, and more... LP1-4 WEDNESDAY, July 8, 2020 www.chinadailyhk.com HK $10 Xi highlights Meeting boosts relations with Argentina, China-Arab ties Dominican Republic amid contagion By AN BAIJIE and MO JINGXI China would like to continue to Event rolls out specific steps for both cooperate with Argentina on fighting COVID-19 and offer assistance to the sides to strengthen strategic partnership South American nation within its capacity, President Xi Jinping said. By CAO DESHENG and MO JINGXI China and Arab states agreed to Xi made the remark while hold the China-Arab summit as exchanging views on disease pre- The COVID-19 pandemic has part of efforts to enhance the level vention and cooperation with brought China and Arab nations of their relationship, Wang Di, Argentine President Alberto Fer- much closer together through the director-general of the Foreign Students take a boat to reach the venue for the national college entrance exam in flood-affected nandez through letters, according to China-Arab States Cooperation Ministry’s Department of West Shexian county, Anhui province, on Tuesday. FANG JUNYAO / FOR CHINA DAILY a statement released on Tuesday. Forum and the mechanism of politi- Asian and North African Affairs, The people of China and Argentina cal parties’ dialogue as they take con- said after the meeting.